Peter Stothard's Blog, page 33

December 26, 2014

Dylan Thomas. Heil! Heil!

By DAVID COLLARD

Dylan Thomas loved film and, as the roster of recent adaptations of his work (and life) suggests, film continues to love Dylan Thomas. As Michael Caines says in the current TLS, had the poet not died young (“too young”), he might have gone on to make a biopic of Charles Dickens – and who knows what else?

In fact Thomas had a brief and productive career in film, writing scripts for wartime propaganda shorts. These Are the Men, made in 1943, suggests his Dickens biopic would have been less than chocolate-box viewing . . .

In a scene from the film Adolf Hitler speaks, but his words are supplied by Thomas:

“I am a normal man. I do not like meat, drink or women. (Heil! Heil!) Neurosis, charlatanism, bombast, anti-socialism, hate of the Jews, treachery, murder, race insanity I am the leader of the German people!”

This brilliantly subversive short was scripted by the poet in collaboration with Alan Osbiston, a young Australian film editor. They were both employed by Strand Films, an independent outfit in Soho producing home front propaganda for the Ministry of Information. Thomas, excused military service, joined the company in the autumn of 1940, on £8 a week.

In the summer of 1942 he wrote to an actress girlfriend called Ruth Wynn-Owen describing his workplace as “a ringing, clinging office with repressed women all around punishing typewriters, and queers in striped suits talking about ‘cinema’ and, just at this moment, a man with a bloodhound's voice and his cheeks, I'm sure, full of Mars bars, rehearsing out loud a radio talk on ‘India and the Documentary Movement’”.

The idea for These Are the Men came from the exiled Viennese writer Robert Neumann (1897–1975), the author of An den Wassern von Babylon (1939; By the Waters of Babylon). As Lea Stöckli recounts in her thesis, Robert Neumanns Roma ‘Children of Vienna’, Neumann had arrived in England in 1938 and been interned as an enemy alien on the Isle of Man early in the war. He was now struggling to earn a living in London as a BBC broadcaster and writer. He was admired by E. M. Forster and his novel The Inquest (1944) was reviewed for Horizon by Anna Kavan. In the early 1940s he drafted a script for an anti-Nazi propaganda short, was unable to interest producers in his approach, and eventually passed the idea on to Thomas, recalling in a journal entry:

Der Film wurde sehr verbessert dadurch, daß ich Dylan Thomas bat, den Text zu schreiben. Für ein zusammenhängendes Gespräch war er, wann ich ihn traf, schon zu betrunken, aber den Text für den Film lieferte er – nicht einen wirklichen “Text”, sondern ein langes Gedicht, das ich quer durch das Ganze unter die Bilder legte.

(The film was greatly improved by the fact that I asked Dylan Thomas to write the text. When I met him he was too drunk for a proper conversation but he delivered the text for the film – not a true script, but, rather, a long poem that I could use to accompany the images.)

You can see most of These Are the Men on YouTube.

As the opening credits appear we hear the drone of the Horst Wessel song accompanying shots of the Nuremberg Rally lifted from Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary Triumph des Willens (1935). Then we cut to stock footage of bakers and foundry workers and fishermen and farmers accompanied by simple lyrical verses by Thomas:

Who are we?

We are the makers, the workers the bakers

Making and baking bread

all over the earth

in every town and village

in country quiet,

in the ruins and wounds of a bombed street

with the wounded crying outside for the mercy of death in the city.

Thomas, a documentary pro, knew the rule of thumb when working with a shot list (a brief summary of each scene, describing the subject matter and action, and giving its length, usually in feet and frames). With practice (and a stop watch), a writer could get used to an established standard of three syllables to the foot on 35mm film and seven syllables to the foot on 16mm.

The tone darkens as we see images from battle zones from “the streets of never-lost Stalingrad” to “the tank-churned black slime of Tunisia”, accompanied by another list:

We are the makers, the workers, the wounded,

The dying, the dead,

The blind, the frostbitten,

The burned, the legless, the mad.

The speaker’s voice becomes increasingly stern and sepulchral until an unexpected moment when Neumann's brilliant idea suddenly takes shape before our eyes. The commentary directs our attention to those responsible for “the battle yard of spilt blood and split bones” and we cut to hands raised in a Hitlerian salute and crowds chanting. More footage from Riefenstahl’s Triumph isaccompanied by a long, tension-building drum roll culminating in shots of Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Martin Bormann and Rudolf Hess, followed by silence for a few seconds before Hitler takes the stand and begins to speak. But it’s an English voice we hear as the leader begins to deliver a rambling confession of his failings,

“I was born of poor parents. I grew into a discontented and neurotic child. My lungs were bad. My mother spoilt me and secured my exemption from military service. Consider my triumphant path to power . . .”

The rest of the Nazi high command gets the same treatment as they line up to proclaim their criminal inadequacy, cruelty, anti-Semitism and moral corruption. Bormann (who gets off rather lightly) describes his incarceration in mental institutions for drug addiction, adding:

“I am a normal man. Twice married; twice mad. Gangsterism! Brute force! Wealth for the few! Cocaine . . . and murder!”

This is both funny and unsettling – a witty deflation of Riefenstahl’s overblown film and the crass, inflationary rhetoric of Nazism. It anticipates by seventy years an enduring internet meme, adapting Neumann’s approach, in which facetious English subtitles are added to a scene in Der Untergang (Downfall), the film directed in 2004 by Oliver Hirschbiegel featuring a remarkable performance by Bruno Ganz as Hitler. There are now over a thousand of these, this being a favourite.

These Are the Men is included in its entirety on Dylan Thomas – The War Films Anthology, a DVD collection of eight Thomas-scripted propaganda shorts issued in 2007 by the Imperial War Museum in London.

December 23, 2014

Period plausibility and the gospel narratives

The nativity play at Pennywell Farm Activity Centre near Buckfastleigh in Devon, 2008.

By RUPERT SHORTT

The birth and infancy narratives in Matthew’s and Luke’s gospels look like sitting targets for the sceptic. Accustomed to conflations of the two narratives made in many a carol and Nativity play, believers can also be shocked to learn that the biblical accounts contradict one another at almost every stage. The only substantial points on which they agree are that Mary and Joseph travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem before Jesus’s birth in a stable (Luke) or house (Matthew). The genealogies at the start of either gospel are irreconcilable. Matthew is silent about the shepherds, and the tale of Zechariah and Elizabeth. Luke’s story knows nothing of the Wise Men, the slaughter of the innocents, or the flight into Egypt.

One inference made by the debunkers – who range from revisionist Christians to non-believers such as Philip Pullman and Colm Tóibín – is that the gospels aren't to be trusted. Christians may reply that taking any gospel passage as a neutral report is to display a level of innocence comparable to that of a fundamentalist believer. In other words, we must put aside our literalist (and typically modern) mindsets to grasp the core point that Matthew and Luke were arguing from conclusion to premiss. Everything they wrote was designed to bear out the belief that Jesus was the Messiah. If, as both evangelists thought, the Old Testament had prophesied that “a virgin shall conceive”, then that must have been what happened in Mary’s case. One of Matthew’s abiding messages is that Christ is the new Moses. Among much else, this accounts for the parallels between the infant Jesus and the Old Testament law-giver, who also evaded a slaughter of male Jewish babies when he was hidden in the bulrushes.

The Jewish element is vital, given the widespread view, pioneered by liberal theologians in the nineteenth century, that the teaching of a devout rabbi was totally recast once Christianity had been uprooted from its Palestinian setting and transplanted into alien Hellenistic soil. In the process, so the argument runs, a charismatic preacher was changed into the divine saviour of all.

Over recent decades, however, Christians defending the integrity of the biblical version have done so precisely by attending to the Palestinian context. Their argument is that the roots of later doctrine lie very much in the characteristically Jewish elements of Jesus’s ministry. Examples of this include his battle with the Pharisees over uncleanliness. Jesus seems to be saying, “How you relate to what I am and what I say is going to shape how you relate to God”. In other words, he is rewriting the rule book and redefining what it means to be part of God’s people. As a leading cleric puts it, Jesus “is acting like the God who chose Israel in the first place. In the Old Testament God had chosen his cluster of slaves to be a people; and Jesus, in choosing his fishermen, tax collectors and prostitutes, repeats and re-embodies this moment of choice: he claims a creative liberty for himself that belongs strictly to God”. So here, on a Christian understanding, is a human life so shot through with the purposes of God that early believers could speak of it as God’s nature projected onto the screen of history. As the author of the Letter to the Colossians put it within a few decades of the crucifixion, in Christ, “all the fullness of God was embodied”.

Period plausibility is of course a necessary but not sufficient condition for believing Christianity to be true. Whether one accepts the creed as a whole is another matter. If, however, you are sitting down this Christmas to read works like Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ, or Tóibín’s The Testament of Mary, my advice would be not to digest them on their own.

December 22, 2014

The TLS 2014

By TOBY LICHTIG

One of the many joys of digital technology is the flexibility it gives us editors to present our content in different ways. Last year, to celebrate the launch of the TLS app, we put together a selection of pieces from 2013 in a free digital edition. Now we are, by what I like to think is popular demand, doing it again.

The TLS 2014 issue takes in a broad sweep of what we do: from neuroscience to classics, anthropology to literature and the performing arts. It is by no means comprehensive, but the idea is to give a flavour of the range of topics that we cover – and different voices in which we do so.

Articles in this free issue include Adam Thirlwell on the infinite selves of Philip Roth, Lorna Scott Fox on the strange and strained relationship between Mr and Mrs Borges, Eimear McBride on the “extreme vulnerability” at the core of Agota Kristof’s writing, and Janet Currie on Helen McDonald’s H Is for Hawk, a highly popular TLS book of the year and a “touchstone for future memoirs, bibliomemoirs, and writing that deals with the natural environment and the self”.

Original poetry includes Clive James’s magisterial, elegiac “Rounded with a Sleep” and Rachel Hadas’s equally brave and beautiful “Poetreef”. Elsewhere, John Kerrigan considers the “stupendous late-spring flowering” of Geoffrey Hill, Peter Thonemann reflects on Herodotus and the birth of history, Mary Beard enjoys a decidedly non-Euripidean production of Medea, and Nat Segnit applauds 10:04 – Ben Lerner’s “breathtaking” follow up to Leaving the Atocha Station (“rarely has a contemporary author’s second novel so triumphantly consolidated the first).

For many, this selection might be an opportunity to catch up on some pieces you’ve missed over the past year. And for those new to the paper – or occasional readers – we hope it whets your appetite for more of the serious, informed, critical, witty and diverse comment and opinion that is at the heart of what the TLS is all about.

So download, enjoy, and we hope it gives you some pleasant – and stimulating – diversion over the festive period.

December 19, 2014

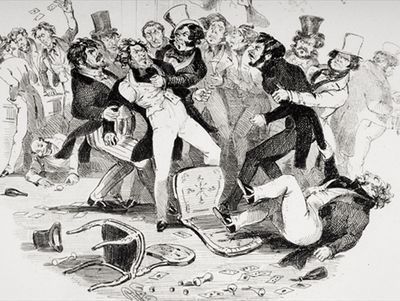

Shakespeare, sex and scholarship

The last brawl between Sir Mulberry and his pupil, illustration from `Nicholas Nickleby' by Charles Dickens (1812–70) published 1839 (litho) (see also 249150), Browne, Hablot Knight (Phiz) (1815-92) / Private Collection / Ken Welsh / Bridgeman Images

By MICHAEL CAINES

Around the time I was writing on the blog about a rediscovered copy of Shakespeare's First Folio, the newspapers were catching up with a Shakespeare-related debate from the TLS letters pages.

It had begun back in September with a book review by Jason Scott-Warren, in which he referred to the "primarily homosexual context" of the Sonnets. Not so, said another contributor, Professor Brian Vickers, in a letter published the following week; it was "anachronistic" to suggest that the Sonnets could not be, in part, about male friendship, as well as a heterosexual relationship between an unnamed female addressee and the poet.

Or a "poet-persona", maybe? "Autobiographical interpretations are fictive", Vickers threw in, just to make sure the whole thing caught fire . . . .

And so it did, with Arthur Freeman writing in later in October to challenge his "friendly acquaintance"'s views on both Sonnet sexuality and biographical readings of the poems. Others followed, and there was, sure enough, a story in that worthy of both the broadsheets and the tabloids – Shakespearean scholars clash over "gay" bard, as the Daily Telegraph put it, while John Sutherland mischievously noted in the Guardian that this was a "wholly academic" debate about sex between scholars "well into their Polonius years with a combined age of 155". The Sun's headline was "Romeo Meets Julian", with a Little Britain-inspired sidebar asking if Shakespeare had been "The Only Gay in Stratford-upon-Avon?".

It's telling in itself that only some people could view this debate with detached bemusement. Others have found it exasperating for different reasons – "who cares?" and "we know all this already" being two possible reactions – and the opportunity to come out with one's own pet theory about the Sonnets hasn't been overlooked, either (the "Dark Lady" is Christopher Marlowe, the Rival Poet Elizabeth I etc).

There certainly isn't anything new about either scholars clashing over what Shakespeare's works mean or exposing one another's assumptions about the shape of his life. The TLS archives are full of variations on this theme. George Bernard Shaw, A. W. Pollard and John Dover Wilson participated in one lively exchange, for example, in the spring of 1921, about Shakespeare's compositional process (it's reproduced in The TLS on Shakespeare, a little book I co-edited with Mick Imlah a while ago). Apart from anything else – Shaw would pack off Dover Wilson to "an asylum for hopeless illiterates" – they cannot even agree on whether to spell the playwright's name with a terminal e.

That disagreeable e shows how these clashes can be coloured by the eccentricities of their time. They tell us something about the present now past, as it were, and not just the distant past. If these squabbles were just squabbles, there would be little more to say about them. But they have a tendency of opening up into wider debates, as well as closing down into personal spats and nitty-gritty, "yes, but" pedantry. One case that comes to mind is now forty years old:

In January 1974, the recently installed Warton Professor of English at Oxford, John Bayley, suggested in the TLS that the "man right fair" of Sonnet 144, his "better angel", was not a younger man at all but Shakespeare himself – or rather, a part of Shakespeare himself. "The equivalence seems obvious, once made", Bayley wrote, with lines such as these in mind, in which "Hell" figures as "the cant term for the pudenda of a prostitute":

To win me soon to hell, my female evil

Tempteth my better angel from my side.

This was, in other words, a sonnetteer who "could never resist a quibble or a pun" and who "well knew that the most searingly painful personal experience not only has its absurd side even for the victim, but for others . . . is merely – and continuously – a source of entertainment".

Complicating what happened next was a further attempt to amuse, rather than a straightforward attack on the seeming vulgarity of Bayley's reading of the Sonnets. In fact, Bayley's reading was welcomed two weeks later, in a letter from the author of a book with further things to say about ambiguity. And in the same issue appeared a letter from a more senior Oxford eminence, John Sparrow, the Warden of All Souls.

Seemingly emboldened by Bayley's method of arriving at a "striking hypothesis" through "a number of ingenious plays upon the wording of the poet's text", Sparrow offered a taste of his own ingenuity, in the form of a reading of another sonnet by another writer: Milton's "When I Consider How My Light Is Spent". Here the poet (persona or not) laments that his "one Talent which is death hide / Lodg'd with me [is] useless". What could that mean?

With meticulous attention to dates and personal circumstances, Sparrow suggested that Milton wasn't simply talking about his eyesight or his "creative" powers here, but "his procreative powers". Framed by the birth dates of his children and the death of his wife, the sonnet could be made to speak not of a literary anguish but, as in Sonnet 144 and the rest, according to Bayley, a kind of sexual disappointment.

Sparrow's letter was, in fact, an all too straight-faced parody of Bayley's method – something perhaps most clearly signalled by his conclusion: "A true appreciation of the circumstances that inspired the poem surely gives a fuller and more vivid significance to its stoical conclusion: 'They also serve who only stand and wait'". (Bayley, like many a scholarly rhetorician, had frequent recourse to that persuasive word "surely".)

Not even this triumphant detection of a bawdy pun, in Milton's dignified, celebrated closing line, was enough to make Sparrow's readers absolutely certain about what he was up to. Alastair Smart complained of the "risible absurdity" of Sparrow's thesis, and although he suspected it was, as another doubter put it a "brilliant leg-pull", went on to demolish the thesis at length, just to be sure. William Empson joined in, as did Helen Gardner, who sensed some "Swiftian irony" at work, but wished that Sparrow hadn't exercised it on "this poem of all poems":

"Perhaps I am being stuffy in protesting; but this sonnet is one that is often read at school, and many people who had read it when young have found strength and comfort in later life from the courage, humility, and faith with which Milton faces the thought of uselessness."

And so it went on, from early January to late March all told, even after Sparrow had come out and explicitly stated that his Milton letter had been a parody and that he was in fact opposed to the idea that bawdiness abounded and ought to be given unembarrassed prominence in every essay in criticism henceforth.

It's easy to say in retrospect that everybody should have got Sparrow's joke; at the time, nobody could be sure, perhaps precisely because of this general sense that it had become de rigueur to reject stuffiness and draw unembarrassed attention to what previously had been dismissed as obscenity – and maybe wasn't "there" at all, in a phrase such as "man right fair", but in the smutty critic's imagination.

Bayley himself agreed, seeking to distance his own reading of the Sonnets from this, as he saw it, invidious tendency ("now persons like Kenneth Tynan suggest that we have a civic obligation to enjoy the crudest kind of sexual display or description whenever or wherever presented"). And all could agree that a hapless TLS reviewer had recently erred in exactly this way by likening light verse to –

But you get the idea. There are a few more examples of correspondence from TLS readers that's developed into more than just squabbles over at the TLS Arguments page. When is a scrap not just a scrap? When it's a sign of the times . . . .

December 17, 2014

Bertrand de Fénelon, friend of Proust

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Among the young men Proust fell in love with was Bertrand de Fénelon (above), who is said to have partly inspired one of the novelist’s most attractive creations, Robert de Saint-Loup (like Fénelon, Saint-Loup was an admirer of Wagner, and bisexual). Born in 1878 – and therefore seven years Proust’s junior – Fénelon was killed in battle a hundred years ago today.

For William Carter, one of Proust’s best biographers (2000), Fénelon was “as handsome as he was distinguished, . . . Slightly aloof, blond, and dapper”. He goes on to say, “His ‘bright blue eyes and flying coat-tails’ reappeared among the elements used to create the marquis de Saint-Loup’s special appeal”. “Like Fénelon, Saint-Loup betrays his class by scorning high society and endorsing leftist policies”.

When Proust sent Fénelon a copy of his early collection of miscellaneous pieces Les Plaisirs et les jours (1896), he inscribed the words “. . . in hopes that he will equal the great literary name he bears” (an ancestor, the Archbishop of Cambrai, had written the Aventures de Télémaque, 1699).

Although Proust’s letters to Fénelon have, according to Carter, “remained in the hands of private collectors”, it’s clear that the novelist became infatuated with him and that the feeling wasn’t entirely reciprocated: “At times the prince enjoyed tormenting Marcel [Carter is not above employing a certain familiarity with his subject], who now suffered from terrible jealousy over Fénelon’s frequent coolness toward him”. At one point the novelist “picked up the new hat Fénelon had bought for his trip to Constantinople [where he was to take up a post at the French embassy], ‘stamped on it, tore it into shreds, and finally ripped out the lining’”.

When war broke out, Proust initially “was unaware that . . . Fénelon, who could have fulfilled his obligation to his country by staying in his diplomatic post, had volunteered for active service”. As Adam Watt reminds us in his excellent short biography of the novelist (2013), he “followed the unfolding of the conflict obsessively", reading “as many as seven newspapers each day”. He was “constantly concerned about being conscripted (despite being quite obviously unfit for service) and about being thought of as a shirker”.

In December 1914, Fénelon was reported missing and, as Carter writes, “a letter from his sister to Proust on 17 February intimated eyewitness corroboration of the rumour” that he had been injured. Confirmation of Fénelon’s death didn’t come until March, published in Le Figaro – it’s amazing how slowly news sometimes travelled from the front. Fénelon had taken a bullet to the head while leading an advance, “a scenario”, says Watt, “with which the death of Robert de Saint-Loup in the novel had much in common”.

Proust wrote to an acquaintance: “You can’t imagine how much intelligence, how much heart, how much heroism there was in that exquisite creature”.

December 16, 2014

Christmas with T. S. Eliot

"A Song for Simeon", illustration by E. McKnight Kauffer, 1928; © Faber

By THEA LENARDUZZI

In 1927, Faber & Gwyer, as the publishing house was then known, asked their new employee T. S. Eliot to produce a series of pamphlets, printing new poems by some of the leading lights (including Walter de la Mare, G. K. Chesterton and, albeit on the wane, Thomas Hardy) alongside work by distinguished artists (the Nash brothers, for example, and E. McKnight Kauffer, whose illustration for one of Eliot's own contributions appears above). At that time, Eliot was just resurfacing, not only from ten years in banking, but from his conversion to Anglo-Catholicism. It was only shortly after the first run of pamphlets appeared that Eliot, in a preface to his collection For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays on style and order, famously declared himself a “classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and anglo-catholic in religion”. (Eliot is not the only literary type to acknowledge a debt to Andrewes; for Kurt Vonnegut, the translator of the King James Bible was “the greatest writer in the English language so far”.)

Eliot’s choice of “Ariel” as a title for the series seems particularly pertinent in this light . . . .

The pamphlets were originally intended for Faber’s clients and business associates, designed, as Alan Jenkins explains in the most recent episode of TLS Voices, “to take the place of Christmas cards and other similar tokens that one sends for remembrance’s sake at certain times of the year”. Taking Christmas more or less obliquely as his theme, Eliot brought his creativity to bear on one of the most pivotal, and divisive, events in the Christian calendar. “Ariel” is both the symbolic name – meaning “lion of God” – for Jerusalem, and the name of Shakespeare’s neither-good-nor-bad, sexually ambiguous “spirit”.

If Eliot saw himself as having just arrived at his new faith, he had at the same time only recently departed his previous life as a non-believer. Poised mid-conversion, the speakers of “The Journey of the Magi” and “A Song for Simeon”, two of the poems Eliot contributed to the series in 1927 and 1928 respectively, look forwards and backwards at the same time; these are simultaneously poems of birth and death. This is perhaps nowhere more clear than in the final stanza of “The Journey of the Magi”:

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our palaces, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

While “The Journey of the Magi” draws heavily from the Gospel of Matthew, “A Song for Simeon” borrows from an episode at the end of the Nativity passage in the Gospel of Luke to weave a dramatic monologue of the repentance and conversion of Simeon, an ageing Jew (“I am tired with my own life and the lives of those after me, / I am dying in my own death and the deaths of those after me”). Both poems represent a shift from the abject bleakness of The Waste Land (a relief, no doubt, for those receiving the pamphlet as, in Eliot’s words, “a kind of Christmas card”), but they carry with them a similar sense of alienation and rootlessness, conveying the partial sight of a conflicted, or flawed seer.

This is the work of a poet still very much in the grip of conversion, for whom Christmas – and the Ariel series – represented a kind of test. (When Eliot said of the title, “Nobody else seemed to want [it] afterwards”, he couldn’t have known that Sylvia Plath would write a poem of that name – Ariel was the name of her childhood horse – on her birthday in 1962, a few months before committing suicide; I can think of few poets for whom birth and death were so fused. That the poem went on to give its name to her posthumously published second collection, in 1965, the year of Eliot’s death, seems apt.)

Eliot’s private, spiritual conflict can be seen in the sheer range of the poetry he included in the series, from the near-Hallmark sentimentality of Laurence Binyon’s “The Wonder Night” (“Now firelight pranks the ceiling / Above each sleepy head, / It warms a hand that's clasping / The new toy hugged in bed, / On hair it flickers golden / And cheeks of rosier red”) to Walter de la Mare’s “Alone” (“The abode of the nightingale is bare, / Flowered frost congeals in the gelid air, / The fox howls from his frozen lair: / Alas, my loved one is gone, / I am alone: / It is winter”).

Perhaps it is the near-schizophrenic nature of Eliot’s selection that gives this series its enduring appeal – indeed, in time for this Christmas, Faber have reissued Eliot's own Ariel poems – there were six over the years, including “The Cultivation of Christmas Trees”, published in a 1954 revival of the series – in a single volume, complete with the original artwork. To state the obvious, Christmas means many things to many people, and often these many things can hit the individual all at once. Taken as a whole, the Ariel series dramatizes the full range of emotions associated with the season – it encapsulates the by turns over- and under- whelming period perfectly.

December 14, 2014

Cries of East London

By MICHAEL CAINES

You can't move in twenty-first-century London for Theophrastian stereotypes: Cockneys, Mockneys, Sloanes, Hipsters, City *ankers and the rest. And that's been the case for some time now, to judge from Chaucer's pilgrims – not to mention the sometimes city-derived Characters (1608) of Joseph Hall (see his dissolute "duke of bucks", one who has "dammed up all those lights that Nature made into the noblest prospects of the world, and opened other little blind loopholes backward by turning day into night and night into day"); Catherine Gore's Sketches of English Character ("the butler of Russell and the butler of Grosvenor Squares" are "dissimilar in aspect and aspirations as a Guineaman and a Hindoo"); Henry Mayhew's London Characters ("Cabmen bully ladies dreadfully"); or Thackeray's deathless Book of Snobs.

Not to mention that lot, I say . . . .

The example could also be given of the many series of prints collectively known as the "Cries of London" (to complement Les Cris de Paris, the genre's supposed place of origin, as well as those of Rome and Bologna).

These cheap prints, chapbooks etc offer a proto-Dickensian view of the city and its citizens in all their ordinary, cacophonic glory, and range from sixteenth-century woodcuts later bought by Samuel Pepys to John Player cigarette cards from 1916. Buyers of old clothes pass vendors of pet food ("each purring puss / Is pleased my cry to hear"); Covent Garden apparently bubbled over with rival invitations to buy clove-water, horn-books, "Southernwood that's very good!", samphire and "Brave Windsor beans".

It is a broom vendor, hawking his wares outside St Leonard's church in Shoreditch, from the Cries of London by William Marshall Craig, who welcomes you into Adam Dant's modern variation on the characters-and-their-cries theme, 50 People of East London.

Craig's world was that of Sunday morning mackerel-sellers ("four for a shilling"), old men hoarsely offering to repair old chairs, knife-grinders, milk maids and other sweet street hawkers ("Fine China oranges, fine lemons") – all the types that might just make it into a Regency costume drama on television before the camera cuts from the street to the lovestricken heroine (just as much a cliché, but a more popular one), mooning at the window of her guardian's townhouse.

By contrast, Dant's fifty Easterners range across a wider social spectrum: there's the "flat white bore" picture above, rated 2 out of 10 for rarity; the elderly left-wing dad (an "ageing Newsnight producer" who moved to "deepest Hackney" and is "appalled that so many other white people also frequent the local gastro-pub"); the nomadic laptopian; the nasty piece of work; the mini cab tout ("no, you said Kennington, what? Kensington?"); the irritating performance artist; and the Hoxton elderly ("They have spent the last 60 years watching the neighbourhood transform, all the while smoking one very long Rothmans king-size cigarette and gently effing and blinding").

Dant's East London characters are also, for the most part, and in contrast to the modest grafters depicted by William Marshall Craig et al, fairly useless members of society – but still on the make.

East Londoners will have no problem spotting most of Dant's common to medium-rare types. 50 People ends by inviting readers who have "good photos" of forty of more of them to send them to the publisher, the year-old Hoxton Mini Press.

This is one of those small presses I threatened to write about after the small publishers fair last month; their other publications include Shoreditch Wild Life and Martin Usborne's I've Lived in East London for 86 ½ Years, about a pensioner who has only left town once, to go to the seaside with his mother. I'm impressed by their enthusiasm for Hackney and its environs ("one of the most creative, vibrant, and ever-changing areas of London"); and it makes me wonder why exactly they should have emerged where they have and not somewhere else.

There are stereotypes elsewhere, surely; but does nobody have an equivalent affection for them in the west or north or south? Mockable as many of Dant's East London types are, how come they've all ended up over there? And are other bits of London, where mockers like me live, for some reason ashamed to give their own cries?

December 12, 2014

The Marquis de Sade 200 years on

The Marquis de Sade by Charles Van Loo, 1760–62

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

It’s just over 200 years since Sade’s death (December 2, 1814), and the divine Marquis is far from being consigned to outer darkness, as many would wish. In fact, the date has been acknowledged in the recent opening of an exhibition in Paris, at the Musée d’Orsay no less, Sade: Attacking the sun, curated by the Sade specialist Annie Le Brun. It’s on until January 25, 2015. I haven’t been able to see it, but note that Le Monde’s art critic Philippe Dagen, who describes it as “exploring Sade’s “impact on the visual arts”, rates the show as “exceptional”. The museum’s website warns, however, that “the violent nature of some of the works and documents may shock some visitors”.

Donatien Alphonse François de Sade was not a very nice man. There can be little disputing that. In 1763, he was jailed for two weeks for the mistreatment, including flagellation, of a prostitute in a Parisian brothel. Then there was the notorious occasion in 1772 when he and his valet Latour holed up in the Marquis’s chateau at La Coste in Provence with four young prostitutes from Marseille, whom they force-fed aphrodisiacs. Sensing trouble, the two men fled to Italy, accompanied by the younger sister of Sade’s wife, whom he had seduced. The two men were sentenced to death in absentia for attempted poisoning and sodomy, and their effigies burnt in Aix-en-Provence. The sentence was later quashed.

Considered irremediable by the authorities of the ancien régime, and those of the Revolution that toppled it and the Empire that followed, Sade was locked away in prisons and mental asylums for roughly a third of his long life, first in the fortress of Vincennes, then the Bastille and finally the lunatic asylum at Charenton outside Paris, where he remained until his death. When the crowds stormed the Bastille on July 14, 1789, Sade was no longer a prisoner there, having been transferred some ten days before; the governor of the Bastille (what happened to him?) thought it best to get Sade out of the way as he had been shouting out to the rioters outside the prison walls that the prisoners were being murdered.

Even in France, a country not noted for literary prudishness, Sade’s work has not had an easy ride. In 1815 Justine and other works were banned. In 1954 the late Jean-Jacques Pauvert was found guilty of obscenity for publishing an edition of Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome, a work Sade composed in thirty-seven days on both sides of a 12-metre roll of paper while in the Bastille (Sade thought the work destroyed when he was moved to Charenton; it was in fact lost until a certain Iwan Bloch rediscovered it in 1904). As the TLS columnist J. C. noted (NB, October 10), Pauvert was “responsible for plucking the Marquis de Sade from infamous oblivion and setting him on the course to literary respectability”.

Sade finally gained a cast-iron seal of literary approval in France with his appearance in the prestigious Pléiade series in 1990 (what would he have made of that, I wonder) – in three volumes, all edited by the pre-eminent Sade scholar Michel Delon.

Reviewing the first of these in the TLS (February 15, 1991), the eighteenth-century expert David Coward wrote: “Sade’s books are turgid and his ideas as watertight as the muslin cloth in which they deserve to be boiled. Yet he still retains the power to transfix. That he should still do so in the late twentieth century is remarkable”. When he moved on to the second volume (TLS, August 2, 1996), Coward pointed out that Sade “stole ideas shamelessly”, Delon’s “meticulous annotations” revealing the writer’s “indebtedness” to Voltaire, Buffon and Helvétius among others.

The third volume, which came out in 1995 and wasn’t reviewed in the TLS, consists mainly of Histoire de Juliette, an interminable story in which virtue goes unrewarded and vice unpunished – over a thousand pages of closely printed text. This is preceded by La Philosophie dans le boudoir, which appeared in 1795 as a “posthumous work by the author of Justine”. The book’s full title La Philosophie dans le boudoir ou Les Instituteurs immoraux – Dialogues destinés à l’éducation des jeunes demoiselles leaves little doubt as to its content. It takes the form of a dramatic dialogue in the course of which a thorough sex education is handed out to fifteen-year-old Eugénie by the twenty-six-year-old Mme de Saint-Ange (who was herself married at fourteen) and her brother the Chevalier de Mirvel, both acting on the instructions of the homosexual Dolmancé, who sometimes seems like a cruder version of the amoral Valmont in Laclos’s Liaisons dangereuses (1782) – a work that Sade would have known.

It's notable that even Delon struggles to place Sade politically. As he points out, the son of a libertine aristocrat has been held up as a revolutionary and a counter-revolutionary. His status is said to have saved him from the scaffolding, and he himself opposed the death penalty. And of course he despised the church, a sentiment that may have had its origins in his harsh Jesuit education. La Philosophie dans le boudoir contains the reading of a pamphlet entitled “Français, encore un effort si vous voulez être républicains” (one more push if you want to become republicans); yet, as Delon points out, in that story Augustin the gardener is confined to the role of a “sexual animal” – shades of the ancien régime.

Meanwhile John Phillips, the Sade expert and translator of the Oxford University Press edition of Justine, reminds us that the Surrealists had championed the “divine Marquis” as an “arch-transgressor and apostle of freedom”. Phillips nicely characterizes Sade as representing “the dark side of the Enlightenment”.

In a recent article in Le Monde, Delon wrote that Sade’s work has frequently been condemned by those who haven’t troubled to read it and that it took the obstinacy of poets like Apollinaire, Paul Eluard and René Char to bring Sade out of the shadows.

Delon describes the writer’s style as “mêlant le langage de la philosophie au vocabulaire des bordels” (mixing the language of philosophy with the vocabulary of the brothel). And he’s surely right, too, to ask: “Two centuries after his death, is it not time to move beyond the quarrel between right-thinking condemnation and lyrical exaltation?” He goes on to say that, aside from the pleasure yielded by an exceptional literary style (I agree), Sade’s work has great historical interest, crucially sending the reader back to that turning point represented by the passage from a feudal to a liberal society.

To the famous question posed by Simone de Beauvoir in 1952, “Must we burn Sade?”, the answer is unquestionably no.

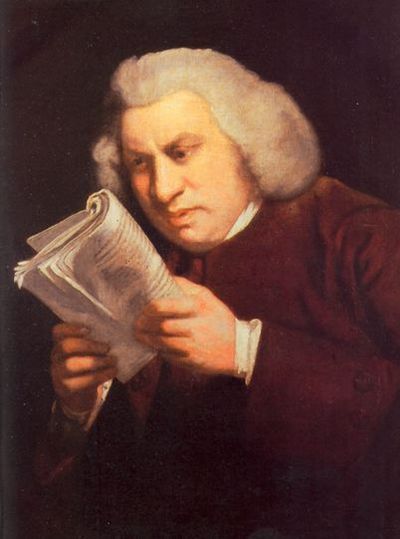

The digital Works of Samuel Johnson

Dr Johnson by Joshua Reynolds (1775)

By CATHARINE MORRIS

In describing the publishing history of the Works of Samuel Johnson at the Dr’s house recently (the history is fascinatingly chequered – more on that at a later date, perhaps), Professor Robert DeMaria, Jr, of Vassar College, the third general editor of the Yale edition, shared a few thoughts about the Yale digital version (free and open to the public), which he and his colleagues launched this year.

It is entirely reliant on the (twenty-one volume) print edition, he said, but it has in a way its own ethos or character. He talked a bit about the process of putting it together. Once a digital text had been created – there was a sharp intake of breath when we were told that the printed pages were not scanned in but typed up by two typists – DeMaria divided it, with the help of his students, into 1,728 “separable and in some way integral pieces” (each of the prayers in Volume One, for example, is a separate piece). And that’s not trivial, he said; any piece can be placed on the screen next to any other.

DeMaria and his students then created the metadata – a spreadsheet with the 1,728 items down the left-hand side and fields such as date of publication, date of composition, genre, publisher and place of publication along the top – which was fed into a digital platform originally designed for the Stalin papers (“These little hammers and sickles would show up . . . . We had to get rid of all of those”). Thanks to the metadata you can now see Johnson’s works arranged chronologically; or you can sort them by genre or publisher. DeMaria suggested that this feature implied "some kind of withdrawal of editorial guidance in favour of readers’ discretion in arranging the materials . . . . Also the barriers between the volumes are broken down. There’s no longer really any such thing as a volume. You can . . . look at the volumes independently if you wish, but you needn’t, and I suspect most people won’t – they’ll search for particular items”.

Another difference, said DeMaria, is that the textual notes are mixed in with the explanatory ones, and they are for the most part out of sight: you click on the relevant letter or number and you’re whisked to a separate area at the end of the section. (Incidentally, you can also add tags or notes yourself, and start discussions with other readers.) Is there a cognitive difference, DeMaria wondered, between “the circumstance in which the eye moves up and down the page” and in which the eye is, effectively, directed to a new page? He thinks that there might be.

It’s possible, using the search devices, to find all the places where Johnson uses a particular word, which is “sort of possible with indexes in printed books, but only very good ones”. There is also a list of keywords, which enables readers to order Johnson’s work by theme or topic.

And this, he said, is something that requires some meditation too: “I think our minds might do that kind of organization anyway when we read a lot . . . . The tool of searching empowers the reader . . . but it also deprives him or her . . . because it reduces the amount of time we spend reading before deciding on classifications. In that time, I think, something creative may be going on that the availability of predetermined classification shuts down. That period of reading when we’re just seeing textual moment after moment without putting it together is the period when we are most likely to develop our own original views and perhaps develop the deepest impressions of a writer”.

This is one aspect of digitization that I hadn’t considered before, and I’d be interested to hear others’ thoughts on it . . . .

December 9, 2014

Great stations and modest journeys

Photo: AP Photo/Alastair Grant

By MICHAEL CAINES

"I waited for the train at Coventry" is what Tennyson did that led him onto the subject of Lady Godiva in 1840. Around the same time, Hawthorne is waiting to set out along his mock-Bunyanesque "Celestial Railroad", at the "very neat and spacious" Station-house – where Bunyan's Evangelist has found steady employment at the ticket office.

A history of literary train journeys might race on from here to La Bête Humaine and Anna Karenina, then to the cross-country pursuit of Richard Hannay (including his unorthodox disembarkation from a temporarily stilled train out of Galloway into a "tangle of hazels which edged the line"), Louis MacNeice on his reflection "lonely in the moving night" (and "half-thought thoughts" on the "Train to Dublin"), W. H. Auden's "steady climb" to Beattock, and onwards, ever onwards . . .

Despite the odd exception, such as the daydreaming Tennyson, I reckon that a survey along these lines (sorry) would show the old masters to be in general agreement that – as the plucky modern proverb has it – it is the journey that matters, not the destination, and certainly not the point of departure.

And even the journey could be unworthy of comment. "There was, however, a midday train which would reach Paddington in the afternoon", notes Trollope's Miss Mackenzie (in the story of the same name), dashing off to get her bonnet and send a telegram. A little conversation passes before she is even in her carriage, and a new scene opens: "At the Paddington Station Miss Mackenzie was met by her other lover . . .". The midday train plummets silently into the gap between paragraphs.

Edward Thomas's "Adlestrop" must be the most famous exception to this authorial fondness for hurtling around, but it may present too rosey a view of being stuck at a station for the modern commuter. Metropolitan overground trains seem to spend as much time trundling as hurtling; and many writers seem to have perfected the art of avoiding the busiest stations during rush hour. Who has best captured such ordinary experiences, I wonder?

The last time I found myself at a country station, only the signal box was manned; a notice instructed customers to buy their tickets at the machine, and the machine was broken. On the train, my card wouldn't work and the cost of my single ticket was three times what had been suggested online. I eventually bought my ticket at the end of the branch line for a little less and made my connection back to Liverpool Street with a few seconds to spare. It was neither the smoothest of train journeys nor a hold-the-press disaster – just an ordinary British, muddling-through afternoon, redeemed by the Thomas-like stillness of its nondescript starting point, a boarded-up Suffolk station, its array of cold chimneys pointing purposelessly at the high cloudlets.

I guess somebody becalmed on a homeward journey like that could do a lot worse than just looking around them. There's some encouragement to do so in one of the latest of the ceaseless internet's lists: ten great English railway stations as chosen by English Heritage.

It's not intended as a "definitive list", English Heritage point out, but "just for fun". A "lively" debate has followed. How dare the compilers of the list select Windsor and Eton Riverside ("perhaps the most playful station designed by Sir William Tite") and ignore Darlington Bank Top? – and so on. (See the Independent for a summary.)

Greatness, according to English Heritage, stretches from the necessarily massive London termini and the perhaps less predictable grandeur of Monkwearmouth (now a museum) to the Tudor pastiche of Wolferton in Norfolk. Scale matters; St Pancras boasts a trainshed built in 1860s that was the "largest man-made span in the world" at the time, and held the record for the next two decades. Smaller stations must find other ways to impress.

Have these implicit criteria changed much since the nineteenth century? I suspect that the authors of London and Its Environs: A practical guide to the metropolis and its vicinity (1862) would have agreed with English Heritage's top ten. The grand dimensions of Euston and King's Cross were just as impressive 150 years ago, unlike London Bridge ("a cluster of stations, irregularly combined, and without any unity of plan or architectural beauty") or Waterloo ("The station is spacious, but makes no pretence to architectural effect"). Second on the modern list, meanwhile, comes John Dobson's "classical tour-de-force", Newcastle Central Station; it was described as one of the "most elegant and commodious stations in the kingdom" in A Hand-Book to Newcastle upon Tyne of 1863.

Photo: SSPL/Getty Images

If notions of what is great about railway journeys and railway stations – not just the architecture, although that, too – have remained fairly consistent over the years, some details in railway literature have remained much as they were, while others have disappeared altogether.

Porters and valets are often on hand to help in the imagined Victorian Victoria. Waterloo sounds incredibly efficient in the "very every-day scene" with which Dickens's friend Percy Fitzgerald opens The Second Mrs Tillotson, "with the train setting off, and cabs arriving with marvellous punctuality, at precisely the last minute". The "evening train" in question perhaps starts unwillingly out of the station today much as Fitzgerald imagines it "toddled" towards the provinces, but the compartments containing just a "prisoner or two" and others that are "merely empty cells" tell a different story. (Perhaps Mr Farage could explain that, too, following his recent success describing the intimate connection between immigration and congestion on the motorways.)

On the other hand, there is the journey to Limmeridge House via Carlisle (and the sandstone porte-cochère designed by the Sir William Tite in 1847) described by Wilkie Collins in The Woman in White: "As a misfortune to begin with, our engine broke down between Lancaster and Carlisle. They delay occasioned by this accident caused me to be too late for the branch train, by which I was to have gone on immediately. I had to wait some hours . . ." Collins doesn't reveal if admiration of Tite's work helps to pass the time.

Then there's Mary Elizabeth Braddon's novel The Cloven Foot (1879), which features one of the classic discouraging thoughts about taking public transport:

"George Gerard thought of the discomforts of a third class carriage, the currents of icy air creeping in at every crack, the incursion of damp passengers at every station, breathing frostily, and flapping their muddy garments against his knees, the streaming umbrellas in the corners, the all-pervading wretchedness . . ."

George is, crucially, imagining these inconveniences while ensconced in a comfortable, warm parlour. I imagine there's a thread, meandering through history, connecting his reluctant vision to the fond recall of Paul Durcan's poem "Sally", in which happiness is actually to be found, albeit briefly, under similarly unpromising conditions:

". . . a dirty cafeteria in a railway station –

In the hour before dawn over a formica table

Confettied with cigarette ash and coffee stains –

Was all we ever knew of a home together."

That's not exactly Tennyson's Coventry. But maybe it's somewhere a bit further down the same line.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers