Great stations and modest journeys

Photo: AP Photo/Alastair Grant

By MICHAEL CAINES

"I waited for the train at Coventry" is what Tennyson did that led him onto the subject of Lady Godiva in 1840. Around the same time, Hawthorne is waiting to set out along his mock-Bunyanesque "Celestial Railroad", at the "very neat and spacious" Station-house – where Bunyan's Evangelist has found steady employment at the ticket office.

A history of literary train journeys might race on from here to La Bête Humaine and Anna Karenina, then to the cross-country pursuit of Richard Hannay (including his unorthodox disembarkation from a temporarily stilled train out of Galloway into a "tangle of hazels which edged the line"), Louis MacNeice on his reflection "lonely in the moving night" (and "half-thought thoughts" on the "Train to Dublin"), W. H. Auden's "steady climb" to Beattock, and onwards, ever onwards . . .

Despite the odd exception, such as the daydreaming Tennyson, I reckon that a survey along these lines (sorry) would show the old masters to be in general agreement that – as the plucky modern proverb has it – it is the journey that matters, not the destination, and certainly not the point of departure.

And even the journey could be unworthy of comment. "There was, however, a midday train which would reach Paddington in the afternoon", notes Trollope's Miss Mackenzie (in the story of the same name), dashing off to get her bonnet and send a telegram. A little conversation passes before she is even in her carriage, and a new scene opens: "At the Paddington Station Miss Mackenzie was met by her other lover . . .". The midday train plummets silently into the gap between paragraphs.

Edward Thomas's "Adlestrop" must be the most famous exception to this authorial fondness for hurtling around, but it may present too rosey a view of being stuck at a station for the modern commuter. Metropolitan overground trains seem to spend as much time trundling as hurtling; and many writers seem to have perfected the art of avoiding the busiest stations during rush hour. Who has best captured such ordinary experiences, I wonder?

The last time I found myself at a country station, only the signal box was manned; a notice instructed customers to buy their tickets at the machine, and the machine was broken. On the train, my card wouldn't work and the cost of my single ticket was three times what had been suggested online. I eventually bought my ticket at the end of the branch line for a little less and made my connection back to Liverpool Street with a few seconds to spare. It was neither the smoothest of train journeys nor a hold-the-press disaster – just an ordinary British, muddling-through afternoon, redeemed by the Thomas-like stillness of its nondescript starting point, a boarded-up Suffolk station, its array of cold chimneys pointing purposelessly at the high cloudlets.

I guess somebody becalmed on a homeward journey like that could do a lot worse than just looking around them. There's some encouragement to do so in one of the latest of the ceaseless internet's lists: ten great English railway stations as chosen by English Heritage.

It's not intended as a "definitive list", English Heritage point out, but "just for fun". A "lively" debate has followed. How dare the compilers of the list select Windsor and Eton Riverside ("perhaps the most playful station designed by Sir William Tite") and ignore Darlington Bank Top? – and so on. (See the Independent for a summary.)

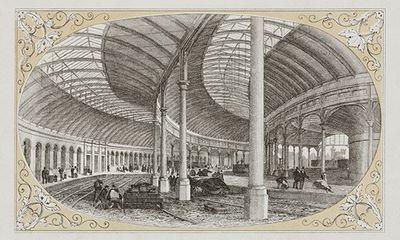

Greatness, according to English Heritage, stretches from the necessarily massive London termini and the perhaps less predictable grandeur of Monkwearmouth (now a museum) to the Tudor pastiche of Wolferton in Norfolk. Scale matters; St Pancras boasts a trainshed built in 1860s that was the "largest man-made span in the world" at the time, and held the record for the next two decades. Smaller stations must find other ways to impress.

Have these implicit criteria changed much since the nineteenth century? I suspect that the authors of London and Its Environs: A practical guide to the metropolis and its vicinity (1862) would have agreed with English Heritage's top ten. The grand dimensions of Euston and King's Cross were just as impressive 150 years ago, unlike London Bridge ("a cluster of stations, irregularly combined, and without any unity of plan or architectural beauty") or Waterloo ("The station is spacious, but makes no pretence to architectural effect"). Second on the modern list, meanwhile, comes John Dobson's "classical tour-de-force", Newcastle Central Station; it was described as one of the "most elegant and commodious stations in the kingdom" in A Hand-Book to Newcastle upon Tyne of 1863.

Photo: SSPL/Getty Images

If notions of what is great about railway journeys and railway stations – not just the architecture, although that, too – have remained fairly consistent over the years, some details in railway literature have remained much as they were, while others have disappeared altogether.

Porters and valets are often on hand to help in the imagined Victorian Victoria. Waterloo sounds incredibly efficient in the "very every-day scene" with which Dickens's friend Percy Fitzgerald opens The Second Mrs Tillotson, "with the train setting off, and cabs arriving with marvellous punctuality, at precisely the last minute". The "evening train" in question perhaps starts unwillingly out of the station today much as Fitzgerald imagines it "toddled" towards the provinces, but the compartments containing just a "prisoner or two" and others that are "merely empty cells" tell a different story. (Perhaps Mr Farage could explain that, too, following his recent success describing the intimate connection between immigration and congestion on the motorways.)

On the other hand, there is the journey to Limmeridge House via Carlisle (and the sandstone porte-cochère designed by the Sir William Tite in 1847) described by Wilkie Collins in The Woman in White: "As a misfortune to begin with, our engine broke down between Lancaster and Carlisle. They delay occasioned by this accident caused me to be too late for the branch train, by which I was to have gone on immediately. I had to wait some hours . . ." Collins doesn't reveal if admiration of Tite's work helps to pass the time.

Then there's Mary Elizabeth Braddon's novel The Cloven Foot (1879), which features one of the classic discouraging thoughts about taking public transport:

"George Gerard thought of the discomforts of a third class carriage, the currents of icy air creeping in at every crack, the incursion of damp passengers at every station, breathing frostily, and flapping their muddy garments against his knees, the streaming umbrellas in the corners, the all-pervading wretchedness . . ."

George is, crucially, imagining these inconveniences while ensconced in a comfortable, warm parlour. I imagine there's a thread, meandering through history, connecting his reluctant vision to the fond recall of Paul Durcan's poem "Sally", in which happiness is actually to be found, albeit briefly, under similarly unpromising conditions:

". . . a dirty cafeteria in a railway station –

In the hour before dawn over a formica table

Confettied with cigarette ash and coffee stains –

Was all we ever knew of a home together."

That's not exactly Tennyson's Coventry. But maybe it's somewhere a bit further down the same line.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers