Peter Stothard's Blog, page 35

November 21, 2014

Taking on ‘The Outsider’

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

As is well known, Meursault’s victim in Albert Camus’s novel L’Etranger (The Outsider) didn’t have a name. He’s referred to throughout as “the Arab”. Now the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud has given him a name, Moussa, in his first novel, Meursault, contre-enquête. The book narrowly failed to win this year’s Prix Goncourt, which has gone to Lydie Salvayre for Pas Pleurer (the TLS has a review of Daoud’s book and will also be reviewing Salvayre’s).

Daoud has essentially written a strong response to Camus’s classic text, which, according to the biographer and critic Pierre Assouline, is still imposed on all lycée students. The author’s purpose is also to give Moussa, “l’Arabe”, the identity denied him by Camus. And there are several echoes of Camus’s novel in the new book, which is of similar length. The name Moussa is clearly meant to make us think of Meursault. The notorious opening of L’Etranger – “Aujourd’hui, Maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas” (“Mother died today. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can't be sure”) – has its counterpoint in Daoud’s “Aujourd’hui, M’ma est encore vivante”.

We learn that Moussa is twenty-seven when he’s killed, and that his body is never found. His much younger brother, Haroun, the narrator of Daoud’s novel, is seven years old at the time. Twenty years later, in 1962, as Algeria is moving into independence, Haroun himself murders a pied noir, who had fled into the back streets of Algiers to avoid a possible lynching at the hands of a mob. By the time he comes to tell his story, and that of Moussa and their downtrodden mother, he is in his seventies and drinking alone in a bar in Oran.

Meursault, contre-enquête is certainly a very accomplished debut, one that can stand side by side with Camus’s novel. It represents another triumph for the Arles-based publishing house Actes Sud, who are also the publishers of the very promising Jérôme Ferrari. Recently Actes Sud took out a full-page ad in Le Monde, filled with admiring quotes from reviews of their new author. Impressive stuff.

November 20, 2014

Van Morrison's mystic

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“Who's the Brown Eyed Girl?”, someone called out from the audience at the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, on Monday night. After a pause, Van Morrison replied: “she’s called ‘faction’”. The packed auditorium shook with laughter. “She’s a composite”, Morrison continued, “not based on any one person. It’s the same thing when writing songs as it is with novels and films.”

It was a unique evening – partly because Morrison isn’t known for talking – of “words and music” to launch a book of lyrics, Lit Up Inside, that spans fifty years of his songwriting. Alongside Morrison, Dr Eamonn Hughes (of Queen’s University Belfast), who helped edit the collection, was joined by the novelist Ian Rankin, the poet Michael Longley and the writer Edna O’Brien who both read selected songs as poems. The second-half of the evening was devoted to Morrison and his four-piece band’s mixture of potent rockabilly- and blues-infused jazz, hymn-like chords and gorgeous melodies.

Hidden behind sunglasses, a black pinstriped suit, black shirt and, of course, black fedora, Morrison was somewhat elusive when answering questions from Hughes and Rankin. But he did give us a rare insight into his creative process. “Moondance” began in 1965 as an instrumental that centred on his saxophone riffs and Mick Fleetwood’s conga drums, until the lyrics were added three years later. “Tore Down a la Rimbaud”, Morrison told us, took eight years to complete, and when he showed Allen Ginsberg the lyrics, Ginsberg, apparently, responded: “Three words: message, purpose, writing. Yeah, you’ve got it”. (Before he picked up a guitar, the young Morrison wrote poems, one of his first being about an Irish shipyard.)

“Coney Island” (which Morrison read to music, and which Longley described as “a celebration of landscape and love”) was inspired by a daytrip in the 1980s to the Ulster coast (not the New York one), which brought back early memories for Morrison – one of his first jobs was as a delivery boy for a bakery in East Belfast, and he would drop off bread to the houses on the seafront. “On and on, over the hill to Ardglass in the jam jar / Autumn sunshine, magnificent and all shining through”.

Rather than telling us, as Rankin asked, how he’d decided when to stop repeating “mystic eyes” at the end of his song of that name, Morrison revealed that it was based on the scene when Pip stares at his parents’ gravestone in Great Expectations. The lyrics in full:

One Sunday mornin’

We went walkin’

down by the old graveyard

In the mornin’ fog

And looked into

Yeah

Those mystic eyes, mystic eyes, mystic eyes, mystic eyes

Mystic eyes, mystic eyes, mystic eyes, mystic eyes

Here’s an impressive performance of the song by Morrison and Them (his first band) – showcasing its overlap with spoken word poetry – at a gig in 1965:

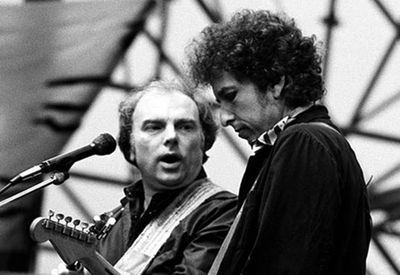

We also watched footage of Morrison jamming “Foreign Window” with Bob Dylan on a mountain in Greece in 1992, the day after a blow-out concert. “There aren't many musicians who can reduce Dylan to second string”, Rankin remarked afterwards. “Well, there’s Harry Belafonte, for one”, Morrison replied. He then spoke passionately about the jazz, blues, country and folk music he grew up with – Sonny Boy Williamson, Leroy Carr, Lightnin’ Hopkins (“how did supposedly uneducated blues singers, like Hopkins, come up with such incredible poetry full of Elizabethan language?”), Ray Charles, Hank Williams and Jimmie Macgregor – all thanks to his father’s record collection, listening to Radio Luxembourg and the show Stars of Jazz on American Forces Network: “I thought it was normal, but realized years later that it wasn’t”.

Indeed, at the Royal Albert Hall’s Blues Fest a couple of weeks ago, Morrison's blues education was very much to the fore in his wonderful re-workings of John Lee Hooker’s songs, “Think Twice Before You Go” and “Boogie Chillen”, interspersed with his own hyped-up skiffle tracks, including “Good Morning Blues” and “Talk is Cheap”. He surprisingly rounded off one of my favourite songs, “Rough God Goes Riding”, with impressions of Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver (“you talkin’ to me”), Al Pacino in Scent of a Woman (“hoo-ah har”) and Clint Eastwood, in just about all of his films (“clop, clop, clop”).

Back to the Lyric Theatre on Monday, where Morrison ended the night with an intense performance of “On Hyndford Street” (a phrase from which the title of his book is taken) from his album Hymns to the Silence (1991). A build-up of tremolo pizzicato from the guitar and double bass, reverberating keyboard and sporadic rumbling drums finally tailed off as Morrison slowly drifted from the stage, his voice still echoing around the theatre.

Watching the moth catcher work the floodlights in the

evenings and meeting down by the pylons

Playing round Mrs Kelly’s lamp, going out to Holywood on the bus

And walking from the end of the lines to the seaside,

stopping at Fusco’s for ice cream

In the days before rock ‘n’ roll

Hyndford Street, Abetta Parade, Orangefield, St Donard’s Church

Sunday six bells and in between the silence there was conversation

Belfast – a source of inspiration, “in the same way as William Blake used London”, Morrison had explained earlier – secular spiritualism, and “a kind of living silence” – as Hughes puts it in the introduction to Lit Up Inside – are the musician's trademarks.

“Anyone who has seen Morrison perform live”, Hughes continues, “will know that he plays with the full dynamic range available to him: he and his band can switch from full-throated roar to stealth mode, as if trying to play silence itself. His words, too, attempt this impossibility.” They are enigmatic – as much a mystery to the creator, it seems, as to the listener – but they warm the soul.

T. E. Hulme’s ways of seeing

By ALAN JENKINS

T. E. Hulme, whose writings from and about the trenches of the First World War are discussed at length in this week’s Commentary by Patrick McGuinness, is one of the most fascinating might-have-beens that the war left in its wake. Hulme is not known principally as a poet of war, or perhaps even as a poet at all – despite having written, according to T. S. Eliot, “two or three of the most beautiful short poems in the language”, and arrived first at the poetic “do’s” and “don’ts” that Ezra Pound took over and christened “Imagisme” (everything then was better in French).

In his lifetime Hulme was admired by Eliot and others for his essays and lectures on art and aesthetics, and for polemical writings in which he excoriated the “romantic” and “liberal” belief in Progress. To this he opposed what he called the “classical” or “religious attitude”: not dependent on organized religion but essentially “a belief in Original Sin”, in the limitations and imperfectibility of man. Only through discipline and order could human nature approach “something fairly decent”. Nevertheless, Hulme thought it self-evident that all men are equal, and that democracy, however repugnant he found it in some ways, was worth defending. In championing the work of avant-garde artists such as Jacob Epstein or David Bomberg his overriding concern was to make their art intelligible to anyone, the man in the street included.

Hulme’s friend (and sometime rival in love) Wyndham Lewis recalled that all his life, Hulme retained his “nagging, nasal, north-country voice” which induced in his listener “an overwhelming sensation of the cussedness of things”. Cussedness was very much Hulme’s style, along with truculence in argument and, on occasion, a relish for physical violence. (He is said to have carried around a knuckle-duster made for him by the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.) When war came Hulme was clear that it was a necessity, if a “stupid” one: fighting wars was, he said, “as useless and as necessary as repairing sea-walls”. This kind of Stoic pessimism served him well as an infantry private. Where other poets and artists saw in war the destruction of everything they held dear, Hulme saw his world-view and his beliefs vindicated.

He was wounded, recovered and returned to the Front as an officer in the Royal Marine Artillery. This ought to have been safer than life as an infantryman, but there was never any question of not returning to the fighting at all. “From time to time”, as Hulme put it, “great and useless sacrifices become necessary, merely that whatever precarious ‘good’ the world has achieved may just be preserved.”

Hulme made the ultimate sacrifice in September 1917, blown to bits by a direct hit from a shell. He was thirty-four. He had by then put his Imagist precepts to good use in his remarkable poem “Trenches: St Eloi” (which you can hear in the latest episode of TLS Voices) . Pound claimed to have transcribed and “abbreviated” it from Hulme’s conversation; it may in fact have been dictated by Hulme to his lover Kate Lechmere. He had also addressed a number of virulently erotic and moving letters to Lechmere – it was on these that I based a poem, “The Jumps”, that appeared in 1914: Poetry remembers, edited by Carol Ann Duffy (life might be mostly dull routine, Hulme thought, but “Poetry comes with the jumps, cf love, fighting, dancing”).

To his Staffordshire relatives, he sent the more restrained, but bracingly unillusioned series of despatches that were published long after his death as “Diary from the Trenches”. Eliot thought that Hulme’s mind ought to be “the twentieth-century mind”; it wasn’t, nor is it likely to be the twenty-first-century one either. But the writings he left in verse and prose, however fragmentary, are not just one of the more distinctive legacies of a long-past avant garde; they suggest ways of seeing and thinking that still seem far in advance of their time, and perhaps ours.

November 19, 2014

Jenny Uglow and John Whiting

BY PETER STOTHARD

Jenny Uglow's artful history of the home front against Napoleon takes me back to a play first produced in the year that I was born - and enjoyed by me in various ways in various later years. From this week's TLS, which also includes a great piece by Emily Wilson on Jimmy Savile.

Last week Bee Wilson was on the TLS cover. This week Emily. Our letters page still resounds with their father, A.N. Wilson's views on translations of Proust. A rare and fine conjunction.

Poetry under pressure

By ANDREW McCULLOCH

Small presses are poetry’s midwives. They are often there, assisting at the birth of great talents. The only poetry Edward Thomas published in his lifetime was the privately printed Six Poems (1916) by “Edward Eastaway”, W. H. Auden’s first outing was “about 45 copies” of Poems (1928) and Seamus Heaney’s Eleven Poems was published by Festival in 1965, a year before his first full collection, Death of a Naturalist. But as well as providing new poets with their first publication, pamphlets can also help published poets to take stock or try something new.

When he founded the Sycamore Press in 1968, the poet John Fuller took as his role model Oscar Mellor’s Fantasy Press, one of whose last publications, Oxford Poetry (1960), he had edited. In the 1950s Mellor had published, among others, Philip Larkin, Thom Gunn, Kingsley Amis and Elizabeth Jennings (a complete seventy-one-volume set of the Fantasy Press now costs well over £6,000). Fuller showed that his editorial impulses were just as accurate at Sycamore, publishing pamphlets by a number of poets who went on to establish important reputations, including James Fenton (Our Western Furniture – his first publication), the late TLS Poetry editor Mick Imlah (The Zoologist’s Bath and other Adventures) and Bernard O’Donoghue (Razorblades and Pencils). The illustration by Julian Bell to one of Sycamore’s Broadsheet poems – “Corncrake” by Andrew McNeillie – is now the logo of McNeillie’s own Clutag Press, which was started when McNeillie salvaged an old Sycamore press from Fuller’s Oxford garage.

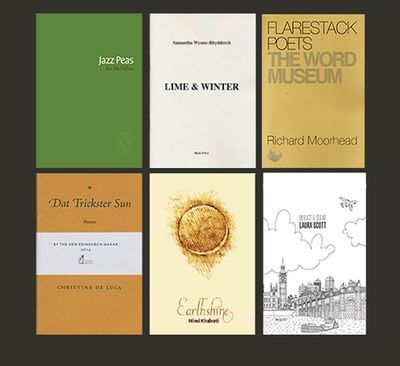

The Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets, organized by the Wordsworth Trust and the British Library [bl.uk/poetrypamphlets] in association with the TLS – and now in their sixth year – were established to recognize and reward those who work to keep this tradition alive. The two £5,000 awards – one for an outstanding poetry pamphlet (maximum thirty-six pages) and the other for an outstanding pamphlet publisher – are designed to help both new and established poets and their publishers develop. It has been a great pleasure to represent the TLS on this year’s judging panel and to join Zaffar Kunial, the Wordsworth Trust’s poet-in-residence and a Faber New Poet, and Tanya Kirk, Lead Curator of Printed Literary Sources at the British Library, in the challenging but immensely enjoyable job of choosing the winners. This year’s shortlists have now been published: the winners will be announced at an awards evening to be held at the British Library on November 25.

The real strength of the pamphlet lies in its brevity. There are obviously economic benefits in producing slim, usually stapled, booklets in limited runs. At about half the cost of a slim volume they are inexpensive enough for readers to take a gamble on an unfamiliar name - you can get all six of this year’s shortlisted titles – Dat Trickster Sun by Christine de Luca; Lime and Winter by Samantha Wynne-Rhydderch; What I Saw by Laura Scott; Earthshine by Mimi Khalvati; Jazz Peas by Ian McMillan; The Word Museum by Richard Moorhead – for just over £30.

But what I find most compelling about pamphlets is the way this brevity so often leads to a satisfying sense of unity and cohesion – as if each individual poem were also part of a single poem. It is a concentrated form and it concentrates the mind. Robert Frost said poetry was “language under pressure”. Squeeze it into thirty-six pages and you can have something very powerful indeed.

---

November 18, 2014

Against unremembering

Henningham Family Press, "Grand Eagle" (detail), 2014; © David Henningham

By DAVID COLLARD

Lytton Strachey, asked what should be done with the instigators of the First World War, reportedly said: “Have them publicly disembowelled at the foot of the Edith Cavell statue.”

This year's centenary commemorations have overlooked the instigators and focused on the dead. Sorrow and pity, not retributive rage, were the keynotes. The Guardian critic Jonathan Jones risked a public disembowelling when he described the installation of 888,246 ceramic poppies (one for every British or colonial casualty of the war) at the Tower of London as “fake, trite and inward-looking . . . a deeply aestheticised, prettified and toothless war memorial”. It is now being dismantled and each poppy sold to raise funds for Service charities, marking a temporary lull in the commemorations.

There's a more thought-provoking response to the Great War on display at the Saison Poetry Library in the Royal Festival Hall. The artists David and Ping Henningham collaborate as Henningham Family Press on essays and poetry which they develop through printmaking, bookbinding and performance. An Unknown Soldier is the title of a three-part artwork consisting of a silkscreen printed birch-ply box containing a long poem split between two slender volumes (Parts I and III) and a series of fine art prints (Part II). The latter, mounted and framed, are complex modernist poetic texts forming the centrepiece of the show.

The poem – also published in a single volume – was prompted by a news item about the way First World War remains are today routinely identified by DNA testing, a forensic development that, David Henningham says, has unwittingly transformed the meaning of the memorial to the Unknown Soldier in Westminster Abbey, whose anonymity (and therefore symbolic value) can no longer be assumed. The unsettling question arises: does The Unknown Soldier now embody our desire to ignore, rather than commemorate, the past? The loss of the definite article in Henningham’s title reflects this uncertainty.

The first part (“Preparatory Oratory”) apes the conventions of remembrance with (the poet says) “a voice like the bastard-child of BLAST and The Book of Common Prayer” in a ferocious assault on sentimental pieties. Here, for instance, is part of a recipe for the creation of a representative of the Fallen:

Wash what you have,

remove mud

remove uniform

the blood will never dry

Get him in soak.

What remains of organs

place in canopic jars

made with haste from defused artillery shells

and hacksawed heads from tin piggy banks

modelled on the war cabinet in caricature

for the savings of boys too young to recruit

(a free gift upon joining a war bond

a free pen for merely making enquiries).

Use rolled up newspaper for a makeshift gasket.

Petroleum Jelly may be required.

There follows a satirical onslaught against modern commemoration in which “Remembrance is now / a wilful unremembering”. That last word appears in Wilfred Owen’s poem “The Show” (1917) and Henningham, wilfully remembering, is clearly alert to such predecessors.

Part II, “An Unknown Soldier”, is a disordered pile of polyglot fragments – a slurred amalgam of English, German, French and Dutch – delivered by a garrulous corpse:

tes ditches est n long, long grave,

unt now un cannot sit in any kind uf furrow, hole od divot,

un sleep af nuh [TOP] bunk

un ride af nuh [TOP] deck

un aviate, un avoid tunnels

un sit in nuh gods

The words in square brackets employ the Henninghams’ bespoke “Trench” font (impossible to reproduce here) and the reader has to pick out the meaning slowly, letter by letter, traversing a lexical minefield.

Part III (“Funeral, March”) offers a brief domestic coda in which reason and benign science succeed chaos and carnage, an affirmation of enduring hope in technology that offers a measure of consolation after the earlier lexical bombardment. There is no room for bitterness, only regretful memory.

An Unknown Soldier is a long way from the canonized verses of Rupert Brooke, Robert Graves, Isaac Rosenberg and Siegfried Sassoon; the romantic aestheticism of their Georgian style was always at odds with the subject although that very tension is of great interest. Henningham’s mordant wit and avant-garde flair is part of another poetic tradition stretching back to Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound and the Dada pranksters of Zurich, although the first truly modernist treatment of the conflict in English emerged only in 1937 with the publication of David Jones's In Parenthesis. (The term “avant-garde”, incidentally, had a purely military significance until used by Olinde Rodrigues in his essay L'artiste, le savant et l'industriel (1825), although its widespread application to modernist art dates from around 1910.)

The Saison exhibition includes other works with a Great War theme, all made over the past three years, including posters which, using the Trench font in brilliant colours, reference call-up papers, wartime propaganda and military instruction manuals; a series of dazzling screen prints commissioned by the Scripture Gift Mission (who during the war distributed 43 million copies of The Gospels of St John to servicemen); a small, elegantly embossed card bearing the word “paradise”, the slang term for the rear of a trench; vitrines displaying the component parts of An Unknown Soldier and a small display of the Saison's poetry holdings, which date from 1912.

This provocative and intelligent exhibition will not suit all tastes, and there are moments when the complex ingenuity of the project threatens to overwhelm both the reader and the subject. It nevertheless brings a much-needed sense of indignation and disgust to present-day rituals of commemoration and gives a voice to the anonymous war dead of all nations without tapping into simple patriotic sentimentality. Mindful of Lytton Strachey’s retributive rage, we might recall the words inscribed on the plinth of Edith Cavell’s statue: “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.”

An Unknown Soldier: An exhibition by Henningham Family Press is at the Saison Poetry Library in the Royal Festival Hall until January 4.

November 15, 2014

The long s and the small publishers

By MICHAEL CAINES

As much as I like a Penguin Classic or a Faber Find, I now find myself increasingly drawn towards the many-splendoured world of art books and sheer odd books – towards the productions of small presses who can’t afford an accountant, let alone an accounts department, and whose tendencies lie in the direction of formal experimentation rather than the usual reassuring formulae.

Perhaps it’s long overdue but I am, belatedly, trying to make up for lost time. A couple of hours at the Conway Hall, at the excellent Small Publishers Fair yesterday, showed me how this Toad of Toad Hall fit of enthusiasm could yet become a bank-breaking if highly enjoyable obsession. . . .

Some suitably small things – badges and postcards – were on sale alongside limited editions hot off the letterpress. A great slab of a book lay closed next to an artistic interpretation of Dracula in a single, delicately cut sheet of black paper. London exhibitors mingled with their counterparts from the Netherlands, Ireland and Mexico. Very little of their work, I imagine, will ever find its way into Waterstones; and for me at least, there’s something deeply appealing about this independent diversity.

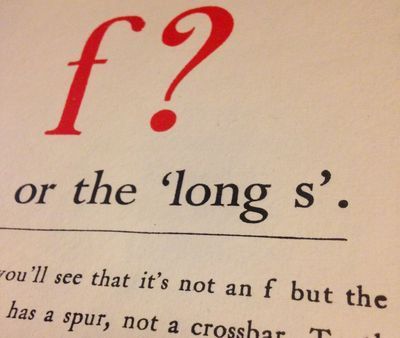

Without meaning to do anything more than find a couple of Christmas presents, I quickly picked up a recent volume of poetry (printed the Lightning Source way), a hand-set reminder of the history of the long s (handy for historians of the eighteenth century; see above) and a couple of apposite postcards from the Perro Verlag stall (one of which boasts Kafka’s line “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us”, which beats hands down “Keep Calm and Carry On”, or whatever that now completely overused template invites you to do).

Enough, surely . . . And then I went round again, hopelessly moth-in-the-presence-of-flame-like, having a fine time talking to the various makers of books (including Michael Nicholson, whose “bio auto graphics” I’ve mentioned already on this blog) and enjoying the small wonders that these small publishers weren’t just there to sell but to exhibit and discuss. Mette-Sofie Ambeck told me how Udkant, a collaboration with Nancy Campbell (an occasional TLS contributor), took shape during the course of a book fair in Denmark:

Another exhibitor told me gleefully about her escape from academia, while a third recalled that he’d taken out an ad with one of the biggest British poetry magazines and sold nothing as a result, in bemusing contrast to what he’d achieved via social media. The chief organizer of the fair (now in its thirteenth year), Helen Mitchell, could say how good it was to have everybody there to talk shop as well as to keep it. Publishing itself, a veteran of these things declared, was a political act; elsewhere, it was a pleasure to encounter the “splenetic anti-verse” of Sean Bonney’s Baudelaire in English and a comparably subversive cousin in the form of Barrie Tullett’s recently published Typewriter Art: A modern anthology.

I hereby confess that this was, in other words, a thoroughgoing biblio-binge, and that I’m not only unrepentant about it, but still in the mood the morning after to recommend to others to enjoy for themselves: the fair ends today at 7pm, and then, all being well, it’s only another twelve months until the next one. And I’ll probably come back to the subject of small presses, fine presses, art books and the like on this blog in the near future, inspired by the work of Tangerine Press, Test Centre, CB Editions and a few others as well as the examples mentioned above. I'm sure you can imagine your own closing line about small being beautiful. . . .

November 14, 2014

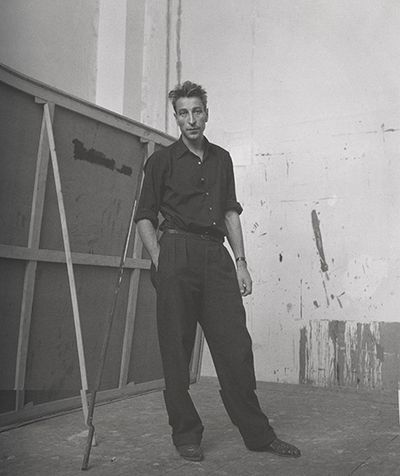

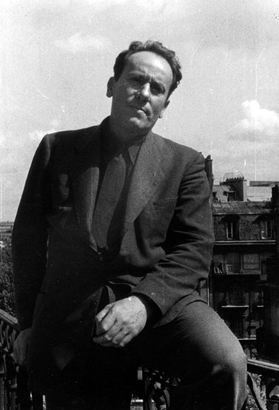

Nicolas de Staël and René Char – an intense friendship

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

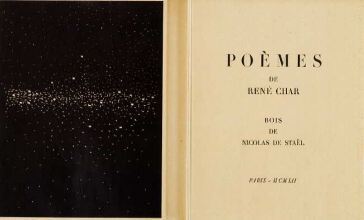

Collaborations between painters and poets are invariably attractive. The brief one between the painter Nicolas de Staël (1914–55) and the poet René Char (1907–88) promised much, but was abruptly terminated by Staël’s suicide at the age of forty-one.

To mark Staël’s centenary, the Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux in Le Havre recently staged an exhibition entitled Nicolas de Staël: Northern Lights – Southern Lights (there was apparently a corresponding show in Antibes, focusing on Staël’s nudes). Le Havre’s light, nicely weathered seafront gallery (which also contains one of the best collections of Impressionist paintings in France) displayed 130 works (80 paintings and 50 drawings), many of them in private hands. These were mainly land- and seascapes – drawings and oil paintings in Staël’s inimitable, transformative style, from the northern French coast to Syracuse in Sicily. In the words of the organizers, “the extraordinary freedom and poetic quality of his work, which straddles the boundary between figurative and abstract art [this was how the artist himself viewed his work], lend it a unique authority”.

"Marine à Dieppe (Plage)", 1952

According to Staël’s daughter Anne de Staël, who has written a preface to a volume of correspondence between Char and her father, published to coincide with the exhibition (141pp. Editions des Busclats. €15), the two produced one book together but planned several further projects. They met in Paris in 1951 and soon became firm friends. Invariably addressing each other as “Mon cher Nicolas” and “Très cher René”, the two men kept up a lively, mutually supportive exchange, occasionally touched by a frenzy of creative excitement on Staël’s part. They were writing to each other from various addresses in Paris and the South of France – Char was from the Vaucluse in the South and very rooted in his region (maintaining his Provençal accent), although he spent time in Paris; Staël meanwhile, constantly in need of money and changing addresses with his young family, moved south late on in his life, first to the medieval village of Ménerbes where he installed his family, and then alone to Antibes in 1954. It was here that he threw himself off his studio terrace.

In between reports from the restless Staël’s travels (Igor Stravinsky is the “most tortuous person he has met” and “a brilliant little gnome”), there is much discussion of the planned book – hermetic poems by Char, beautiful woodcuts by Staël, all amply displayed in the exhibition. At one point Staël refers to “that painter, whose name escapes me, who had himself strapped to the foremast during a storm . . .”; that painter of course being J. M. W. Turner.

Laurent Greilsamer’s biography of Staël (1998, untranslated) is probably the main source for the painter’s life (he has also published a Life of Char, 2005), although it’s not free of that occasional tendency for imagined, reconstructed dialogue. (Why do biographers think this is a good idea?)

According to Greilsamer, Staël’s aristocratic Russian family fled the country in 1919 (his father had been vice-governor of the Peter and Paul fortress in St Petersburg). Both parents died when he was still young and he and his two sisters were taken in by a foster family near Brussels, from where Staël made his way, in his twenties to Paris. An admirer of French culture (who briefly served in the Foreign Legion in North Africa in 1940), he nevertheless didn’t take up French citizenship for a long time.

Marc Chagall described him as “innocent” but “with a cosmic force”. That force is clearly visible in photographs of this most charismatic of painters (above). In fact, if one wanted to think of the ideal of the male artist of the second half of the twentieth century, I think he would look like Staël: an imposing 1m 96 (the solidly built and boulder-headed Char was himself over 1m 90), slim and with an angular face, “gifted with the look of an enchanted bird of prey” in Greilsamer’s words, not for nothing was he known as “the Prince”. Picasso, on first meeting him, looked up and was said to have exclaimed: “Prenez-moi dans vos bras”.

“I know that my life will be a continual voyage on an uncertain sea”, Staël wrote to a friend in 1937. He certainly worked hard, producing 266 works in his final year and, according to Mark Hutchinson, in a TLS review of a Staël retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in 2003 (May 16, 2003), some “700 canvases in three years”!

Hutchinson has just published a new translation of Char’s Feuillets d’Hypnos as Hypnos (79pp. Seagull. £14.50/$21 – to be reviewed in a forthcoming TLS). The book, which, in Hutchinson’s words, “is quite unlike any other book written about the French Resistance”, is based on journals the poet kept during the war, in which he was active as a regional leader, code name Alexandre. (The book was translated into German by Paul Celan.) Mixed in with the aphorisms and fragments characteristic of Char’s often difficult work are some acerbic observations on false heroes of the Resistance: “For every Joseph Fontaine, who has the rectitude and tenor of a ploughman’s furrow, . . . how many elusive charlatans there are . . . . You can be sure that, come the liberation, these cocks of oblivion will be crowing loudly in our ears”.

It’s impossible not to wonder about what drove Staël to suicide. We know that he had become infatuated with a woman called Jeanne – “Je l’aime à crever”, he wrote, alarmingly, to Char. Hutchinson wrote of how he “was living apart from a wife and family he adored but could not live with, tormented by an impossible love affair and racked by doubts about the new direction his painting had taken”. Hutchinson talks of the “palpable melancholy that hangs over so many of his last works”, including the “lumbering” seagulls (above), of which the biographer of Picasso, John Richardson, wrote: “in retrospect, it is easy to see that this painting was a cry for help”. Added to which, Staël was, understandably, exhausted.

Many years later, Char wrote of him, beautifully but rather untranslatably: “Nicolas de Staël, nous laissant entrevoir son bateau imprécis et bleu, repartit pour les mers froides, celles dont il s’était approché, enfant de l’étoile polaire”. It’s hard not to think of the “mers froides” as those lapping his native Russia.

The catalogue to the Le Havre exhibition concludes with a short essay by the painter’s son Gustave de Staël who was five when his father died. He describes the studio he left behind, with its vast, “untransportable” and “unfinished” works. Of the family Staël left behind, Gustave writes: “We were . . . linked by so many unanswerable questions”.

November 13, 2014

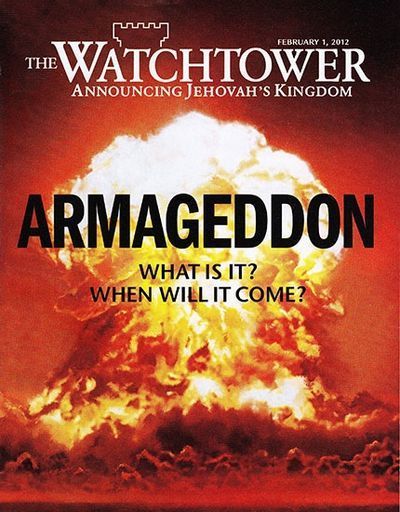

Knocking on heaven’s door

By DAVID COLLARD

It is a striking coincidence that the latest novels by Ian McEwan and Martin Amis both feature characters who are Jehovah’s Witnesses. In McEwan’s The Children Act, Adam Henry, a teenage Witness with leukaemia, refuses to receive a life-saving blood transfusion because he follows the sect’s strict adherence to the Old Testament.

Adam is “exceptional”, “the sweetest fellow”, “a lovely boy” – and entirely unconvincing as a character. A talented violinist who writes poetry wouldn’t last five minutes as a Witness before being taken aside by his congregation’s Elders, admonished and summarily “disfellowshipped” for his adoption of “worldly values”. He would certainly not (as in McEwan’s portrayal) play Benjamin Britten’s musical setting of Yeats’s Down by the Salley Gardens, because Britten was homosexual and Yeats an adulterous occultist, and both were therefore strictly off limits. He would never refer to “God” (as he does in the novel) but always to “Jehovah” or “Jehovah God” or “The Lord Our God Jehovah”. Nothing he says or does rings true, and the same goes for his devout parents.

I know whereof I speak. As a child of Witnesses I lived for years under conditions in which (to quote Auden’s line) “what is not forbidden is compulsory”. This coincided with one of the sect’s regular countdowns to Armageddon, scheduled for some point in 1975 and thus clashing, somewhat unfortunately, with my A-Levels.

How come McEwan, a fine writer, gets so much so wrong? In his acknowledgements he thanks a barrister who is also a Jehovah’s Witness (a combination of allegiances that makes him unrepresentative of either group), and I can’t help feeling the author’s researches stopped there. Did McEwan attend meetings at his local Kingdom Hall? Did he read any of the Witness literature now dispensed freely on street corners? One of the novel’s fictional lawyers reproduces today’s official Witness line on blood transfusions, which emphasizes the medical risks above the older tribal taboos, but both the fictional lawyer and McEwan conveniently overlook the more outlandish and disreputable anti-transfusion arguments the organization has advanced since 1948, when they first decided it was a bad thing.

A past issue of the sect’s flagship magazine The Watchtower (September 15, 1961) quotes approvingly two Brazilian medical men, Dr Américo Valério – who asserted that blood transfusions were often followed by “moral insanity, sexual perversions, repression, inferiority complexes, petty crimes” – and Dr Alonzo Jay Shadman, who claimed that a person’s blood “contains all the peculiarities of the individual”. This kind of nonsense is easy to ridicule, and the current stance does draw more on legitimate scientific research, but the position remains a troubling one. Perhaps the only way fully to engage with the subject is through satire, and McEwan is no satirist.

In The Zone of Interest Amis offers a less detailed but more convincing Witness than Adam Henry in the character of Humilia, who works as a housemaid for the Auschwitz commandant Paul Doll. Humilia has a face “markedly indeterminate as to sex and indeterminate as to age (an unharmonious blend of female and male, of young and old); yet, under the solid quiff of her cress-like hair, she beamed with a terrible self-sufficiency”. Amis makes a compelling point when the commandant’s wife discusses Humilia with a young German officer:

“My husband thinks we have much to learn from them.”

"From the Witnesses? What?”

“Uh, you know,” she said neutrally, almost sleepily, “Strength of belief. Unshakeable belief.”

“The virtues of zeal."

“That’s what we’re all meant to have, isn’t it?”

Amis calls her a Witness, though they were known in Germany at the time as Bibelforscher (“Bible Students”, a term also applied to Adventists and Baptists). From 1935 onwards German Witnesses were subject to intense persecution for their refusal to adopt the Hitler salute or to bear arms. Around 10,000 Witnesses were imprisoned (and forced to wear a purple triangle badge); 2,000 were sent to concentration camps; an estimated 1,200 died in custody, including 250 who were executed.

Humilia’s “terrible self-sufficiency” derives from her absolute conviction that she will never die but will spend eternal life in an earthly paradise, her reward for her unyielding faith. The ghastly conviction of the Nazis was that an elect and perfected humanity would live and rule in a paradisiacal Aryan world order. Both the Witnesses and the Nazis share a tremendous, apocalyptic belief in the purity and sacredness of blood, in its symbolic meaning. They share an eschatology.

In a recent discussion with Alex Clark, McEwan and Amis spoke of their respective novels, Amis confirming that writers are drawn to “extremes, and enclosed systems, things that are a world in themselves” and McEwan adding “We love things going wrong”. How interesting, then, that both writers have used the “enclosed system” of the Jehovah’s Witnesses as an exemplar of things going wrong.

November 11, 2014

Remembrance under attack

A picture frame fashioned from a ration biscuit by Sgt Herring, containing a picture of his children, 1915.

By THEA LENARDUZZI

On Saturday, as David Cameron stooped to plant the final poppy in the Tower of London’s “Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red”, a line from Rudyard Kipling came to mind: “Our England is a garden, and such gardens are not made / By singing: – ‘Oh, how beautiful!’ and sitting in the shade”.

The centenary celebrations seem to have largely focused (for better or worse) on the poppies at the Tower, perhaps causing a distraction from developments elsewhere. Cameron announced that two sections of the display would remain until the end of the month before going on a national tour and ending, in 2018, with a permanent exhibition at the Imperial War Museum (“I think the right place for it to be”). His coalition government, meanwhile, has decided on a £4m cut to the annual funding of the same museum.

Coming just months after the museum’s reopening following a vast refurbishment, the cuts will result in the loss of up to eighty jobs (which will make it increasingly unlikely that the various IWM branches – Duxford, HMS Belfast and the Churchill War Rooms – will be able to accept school visits, for example), as well as the closure of the museum’s library.

The closure of the library is a particularly astonishing way to mark the cententary of the war. The IWM's collection includes over 600,000 items – from photographs, paintings and sound recordings (made in the 1960s and 70s) with veterans of the First World War, to a letter dated November 20, 1914, from Rupert Brooke to Walter de la Mare, in which the poet expresses his fear of England being invaded (“But I’d enjoy fighting in England. How one could die!”), and grave markers carrying the “old lie”. The library is an irreplaceable resource for academics and members of the public researching not only the First World War, but all subsequent conflicts involving Britain and the Commonwealth.

As Freud pointed out, flowers have neither emotions nor conflicts. It falls to us to imbue them with these, and there is perhaps no more successful example of our doing so than the poppy, which, ever since John McCrae’s rondeau first appeared in Punch in December 1915, has become the emblem of our yearly acts of remembrance. Poppies – in their hundreds of thousands or in their singular form as badges – are merely one branch of remembrance, however, and as such are utterly reliant on the experience of war itself, documented in myriad, often unforeseeable ways (for example, pictured above, the army biscuits turned to a more inspired purpose).

But if it must be poppies, you'll find plenty in the IWM’s collections, a rudimentary search of which turned up a letter from Bill, on the Western Front – “hell on Earth” – to his wife Louise Fletcher, dated July 10 1918, with a pressed poppy enclosed (“This I plucked while I was convalescent: a souvenir from France”). You'll also find the notebooks in which Isaac Rosenberg drafted “So shut out are our lives” and “On Receiving News of the War”, as well as a first edition, from 1915, of his privately published pamphlet, Youth. These ephemera are at the roots of any war and if we do not tend to them, any worthwhile remembrance of the whole will struggle to survive.

The Prospect union, representing the IWM, has launched a petition, asking the government to reverse the cuts (you’ll find it here). Before both Kipling and Freud, Cicero put it nicely: “If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers