Knocking on heaven’s door

By DAVID COLLARD

It is a striking coincidence that the latest novels by Ian McEwan and Martin Amis both feature characters who are Jehovah’s Witnesses. In McEwan’s The Children Act, Adam Henry, a teenage Witness with leukaemia, refuses to receive a life-saving blood transfusion because he follows the sect’s strict adherence to the Old Testament.

Adam is “exceptional”, “the sweetest fellow”, “a lovely boy” – and entirely unconvincing as a character. A talented violinist who writes poetry wouldn’t last five minutes as a Witness before being taken aside by his congregation’s Elders, admonished and summarily “disfellowshipped” for his adoption of “worldly values”. He would certainly not (as in McEwan’s portrayal) play Benjamin Britten’s musical setting of Yeats’s Down by the Salley Gardens, because Britten was homosexual and Yeats an adulterous occultist, and both were therefore strictly off limits. He would never refer to “God” (as he does in the novel) but always to “Jehovah” or “Jehovah God” or “The Lord Our God Jehovah”. Nothing he says or does rings true, and the same goes for his devout parents.

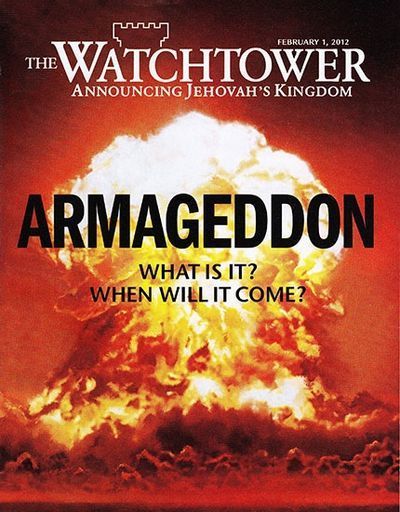

I know whereof I speak. As a child of Witnesses I lived for years under conditions in which (to quote Auden’s line) “what is not forbidden is compulsory”. This coincided with one of the sect’s regular countdowns to Armageddon, scheduled for some point in 1975 and thus clashing, somewhat unfortunately, with my A-Levels.

How come McEwan, a fine writer, gets so much so wrong? In his acknowledgements he thanks a barrister who is also a Jehovah’s Witness (a combination of allegiances that makes him unrepresentative of either group), and I can’t help feeling the author’s researches stopped there. Did McEwan attend meetings at his local Kingdom Hall? Did he read any of the Witness literature now dispensed freely on street corners? One of the novel’s fictional lawyers reproduces today’s official Witness line on blood transfusions, which emphasizes the medical risks above the older tribal taboos, but both the fictional lawyer and McEwan conveniently overlook the more outlandish and disreputable anti-transfusion arguments the organization has advanced since 1948, when they first decided it was a bad thing.

A past issue of the sect’s flagship magazine The Watchtower (September 15, 1961) quotes approvingly two Brazilian medical men, Dr Américo Valério – who asserted that blood transfusions were often followed by “moral insanity, sexual perversions, repression, inferiority complexes, petty crimes” – and Dr Alonzo Jay Shadman, who claimed that a person’s blood “contains all the peculiarities of the individual”. This kind of nonsense is easy to ridicule, and the current stance does draw more on legitimate scientific research, but the position remains a troubling one. Perhaps the only way fully to engage with the subject is through satire, and McEwan is no satirist.

In The Zone of Interest Amis offers a less detailed but more convincing Witness than Adam Henry in the character of Humilia, who works as a housemaid for the Auschwitz commandant Paul Doll. Humilia has a face “markedly indeterminate as to sex and indeterminate as to age (an unharmonious blend of female and male, of young and old); yet, under the solid quiff of her cress-like hair, she beamed with a terrible self-sufficiency”. Amis makes a compelling point when the commandant’s wife discusses Humilia with a young German officer:

“My husband thinks we have much to learn from them.”

"From the Witnesses? What?”

“Uh, you know,” she said neutrally, almost sleepily, “Strength of belief. Unshakeable belief.”

“The virtues of zeal."

“That’s what we’re all meant to have, isn’t it?”

Amis calls her a Witness, though they were known in Germany at the time as Bibelforscher (“Bible Students”, a term also applied to Adventists and Baptists). From 1935 onwards German Witnesses were subject to intense persecution for their refusal to adopt the Hitler salute or to bear arms. Around 10,000 Witnesses were imprisoned (and forced to wear a purple triangle badge); 2,000 were sent to concentration camps; an estimated 1,200 died in custody, including 250 who were executed.

Humilia’s “terrible self-sufficiency” derives from her absolute conviction that she will never die but will spend eternal life in an earthly paradise, her reward for her unyielding faith. The ghastly conviction of the Nazis was that an elect and perfected humanity would live and rule in a paradisiacal Aryan world order. Both the Witnesses and the Nazis share a tremendous, apocalyptic belief in the purity and sacredness of blood, in its symbolic meaning. They share an eschatology.

In a recent discussion with Alex Clark, McEwan and Amis spoke of their respective novels, Amis confirming that writers are drawn to “extremes, and enclosed systems, things that are a world in themselves” and McEwan adding “We love things going wrong”. How interesting, then, that both writers have used the “enclosed system” of the Jehovah’s Witnesses as an exemplar of things going wrong.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers