Peter Stothard's Blog, page 38

October 9, 2014

Germany: Memories of a nation

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This is of course Tischbein’s portrait of Goethe in the Italian campagna. It hangs in Frankfurt’s Städelsches Kunstinstitut and is, in the words of the Director of the British Museum Neil MacGregor, “by far the most famous portrait in the whole of Germany”. Goethe, the national poet and author of the “rambling, unperformable cosmic drama” that is Faust, was the subject of a recent episode in MacGregor’s Germany: Memories of a nation, broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

If there has been anything more fascinating or intelligent on the radio in recent years than MacGregor's current series, then I’m truly sorry to have missed it. Divided into thirty fifteen-minute episodes (we've reached episode 9), these beautifully constructed mini-essays focus on an aspect of German history and culture.The approach is familiar: MacGregor alights on an object, anything from a coin from the Holy Roman Empire to a flimsy wetsuit intended to ease an escape from the old East Germany, to explore wider historical issues.

This idea is of course loosely based on his immensely successful History of the World in 100 Objects, which was broadcast in 2010, with an accompanying handsome book (remember the credit card and solar-powered lamp and charger?).

“One Nation under Goethe” moved from Tischbein’s portrait to the dramatic impact across Europe of the publication of The Sorrows of Young Werther in 1774: not only did young men take to wearing, like their model Werther, blue coats and yellow waistcoats, but there was a “disturbing number” of suicides. But, in the words of one of MacGregor’s interviewees (and MacGregor’s German is excellent), “Goethe is now the symbol of a multicultural Germany”.

The series kicked off, naturally enough, at the Brandenburg Gate, the “national monument” and a “symbol of freedom regained” (the programmes are marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall). The Gate was the first of MacGregor’s chosen objects of enormous significance – an admittedly “rather large” object.

Particularly fascinating was “Kafka, Kant and Lost Capitals” in which the presenter visits Prague (birthplace and home of Franz Kafka) and Kaliningrad (formerly Königsberg and the home town of Immanuel Kant), two cities a thousand miles apart, but both central to German national identity. As is well known, Kant, the founder of German philosophy, never left Königsberg and indeed never set foot inside modern Germany. Kafka was born in Prague in 1883, the year after the last German-speaker resigned from the city council; the dwindling Jewish community of the city kept the flame of the German language alight and MacGregor notes the horrible irony that with the extermination of the city’s Jewish population by the Nazis that flame was extinguished.

In “Strasbourg: Floating City”, MacGregor uses a sixteenth-century clock (above) which was once in the Gothic cathedral (for “hundreds of years the tallest building in the world”), but is now housed in his own British Museum – there is a copy in the cathedral – to examine the fate of what was a “German imperial city” until 1918, became French in 1919, German again in 1940 and French once again in 1944 (which of course it remains to the present day).

Equally fascinating was MacGregor’s story of the two Germanies, East and West, and the tragic stories of failed escape attempts. He reveals that modern-day Friedrichstrasse station in Berlin has no CCTV cameras, such was East Berliners' revulsion at the surveillance society they experienced.

Other episodes have looked at “Fairy Tales and Forests: The Grimms and Caspar David Friedrich” (in which MacGregor reports the astonishing fact that a third of German territory is covered by forests) and “Luther and a Language for All Germans”. Forthcoming are “The Valhalla: Hall of Heroes” (today in fact), Charlemagne (was he French or German?), Dürer, Gutenberg, Hans Holbein, Beer and Sausages, and Bauhaus, among others.

Anyone interested in the past, present and future of Europe should not miss these programmes.

October 7, 2014

Author, Author

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's practical criticism time again (when is it not? I hear you say). Here’s the opening of a novel. Who wrote it? No shouting at the back if you already know:

"Almost everyone thought the man and the boy were father and son.

They crossed the country on a rambling southwest line in an old Citroën sedan, keeping mostly to secondary roads, traveling in fits and starts. They stopped in three places along the way before reaching their final destination: first in Rhode Island, where the tall man with the black hair worked in a textile mill; then in Youngstown, Ohio, where he worked for three months on a tractor assembly line; and finally in a small California town near the Mexican border, where he pumped gas and worked at repairing small foreign cars with an amount of success that was, to him, surprising and gratifying."

The novelist and regular TLS contributor Jonathan Barnes recently showed this passage to a group of creative writing students and challenged them to name the author. Any ideas?

His students made a couple of telling guesses: these were the words of John Steinbeck or John Cheever. I’d like to think the cliché “fits and starts” and that slightly awkward phrase “an amount of success” would have warned me not to make the same suggestions. In any case, the next paragraph should give the game away:

"Wherever they stopped, he got a Maine newspaper called the Portland Press-Herald and watched it for items concerning a small southern Maine town named Jerusalem's Lot and the surrounding area. There were such items from time to time."

The tell-tale phrase here is "Jerusalem's Lot" – the name of a fictional town that turns up frequently in the works of Stephen King, perhaps most famously in his second novel, Salem's Lot (1975). (King recollects in the foreword to a later reissue that the working title was "Second Coming", but his wife thought that could be mistaken for the title of a sex manual; its replacement, "Jerusalem's Lot" was then shortened because his publisher feared it sounded too religious. Oh the joy of trying to please everybody, all of the time.)

As much as I’d like to think, out of pure literary snobbery, that I wouldn’t have mixed up the authors of The Grapes of Wrath and Carrie, I’d also like to think that I wouldn’t have turned my nose up at the first paragraph if I’d already known it was by King, just because he’s popular and readily categorized (all right, dismissed) as a genre writer. I’d like to have my hypothetical critical cake and eat it, if you don’t mind . . .

In the 1960s, I suppose English undergraduates whose tutors confronted them with the same sort of exercise in practical criticism could have taken some comfort from a television series devised by Brigid Brophy, called Take It or Leave It. Anthony Burgess, Bernardine Bishop and other well-read guests would listen as a short piece of writing was read out by an actor; John Bayley, writing about it years later in the LRB, said the idea was “to show off by not showing off”, “to be languidly erudite, wittily and unobtrusively learned”; the whole thing was “élitist to a suicidal degree”. At least in the brief extracts I’ve seen, however, blank-minded silences are just as likely to follow as quick-witted identifications – or good guesses.

Melvyn Bragg recalled that, during his time as the show’s producer, he had chosen a passage from Saul Bellow’s Herzog as a “gift” to two of that week’s panellists, Mary McCarthy (one of the judges who had recently awarded Bellow the Prix Formentor) and John Gross (who had written about Bellow “brilliantly”). “Alas, what the prix judges had described as an unmistakable voice failed the recognition test. Some rather embarrassing guesses were punted . . .”.

On the other hand, no student could field the kind of excuse available to both literary agents (see below) and participants in televised parlour games alike – that nobody can read everything. The right answer, the proper name, isn’t exactly the point. ("There are some books which you know without reading, aren't there?", Robert Robinson hazards in the second of the videos above, after somebody guesses right.) Instead, it might be thought of as criticism for criticism’s sake, an experiment in what Richards, in Practical Criticism, called “developing discrimination”:

“What [poetry] communicates and how it does so and the worth of what is communicated form the subject-matter of criticism . . . . The whole apparatus of critical rules and principles is a means to the attainment of finer, more precise, more discriminating communication."

Perhaps the most mischievous variation on this theme is the kind of test to which the Sunday Times (a paywalled piece, by the way) subjected various unsuspecting literary agents a few years ago: faced with supposedly “new” novels, actually by the Nobel-winning V. S. Naipaul and the Booker-winning Stanley Middleton, only one out of twenty showed any interest in the work – an exposé which was presumably intended to show how standards have fallen etc. I’m more impressed that those clever old journos contacted twenty publishers and agents and apparently received twenty-one replies.

There was a time when the TLS offered its readers the chance to put themselves to much the same test every week, in the manner of practical criticism from I. A. Richards to Take It or Leave It to Jonathan Barnes, with a similar literary guessing game called “Author, Author”, in which a related trio of quotations from different works had to be identified.

Here’s an example from exactly a decade ago, when the prize for the winning entry was £20 and a copy of the newly revised edition of Eric Partridge’s Usage and Abusage. The answers can now be easily found via any reputable search engine – if we ever brought the quiz back, I wonder what kind of literature, if any, would be safe from the same kind of spoilsport technology – but I should think it’s more fun, and in its way good mental exercise, to follow the mutation of the famous lines in the first, famous quotation into the travesty of the last, and try to work it out for yourself.

1 This truth came borne with bier and pall,

I felt it, when I sorrowed most,

’Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

2 What voice did on my spirit fall,

Peschiera, when thy bridge I crost?

“’Tis better to have fought and lost,

Than never to have fought at all.”

3 “Yes,” said I, “you have been inoculated for marriage, and have recovered.”

“And yet,” he said, “I was very fond of her till she took to drinking.”

“Perhaps; but is it not –– who has said: ‘’Tis better to have loved and lost, than never to have lost at all’?”

October 4, 2014

A (fake?) stake through the heart

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's 250 years since Horace Walpole woke from a strange dream and put aside everything to write The Castle of Otranto. With the success of the first edition in 1764, when it was presented as a translation from a sixteenth-century manuscript, Otranto ushered in the age of Gothic literature (and eventually theatre, film, television, music etc). With the publication of a second edition, Walpole revealed the trick, proclaimed his authorship and dubbed it a "Gothic" tale. I haven't read it for years, but the memories of stagey dialogue and enjoyably outsize sensationalism are strong.

The British Library is marking the occasion with Terror and Wonder, an exhibition that opened yesterday; a full review should appear in the TLS soon. For now, though, I'm just going to pick out a single exhibit that caught my eye, on loan to the BL from the Royal Armouries in Leeds, and of uncertain age and provenance:

Photo © Royal Armouries (XII.11811)

It is, of course, a vampire-killing kit.

And, in the spirit of Walpole's novel, it seems highly likely to be an elaborate hoax . . .

Although many people will be familiar with the various objects on show here, and how they could have come in handy if you were trapped in a Victorian novel set in certain remote regions of Eastern Europe, it seems that it was not until the 1980s that kits like this one started turning up with any regularity in auction house catalogues. They usually contain a stake or three, a bible or prayer book, a pistol and so on.

Experts disagreed about their origins. Some constituent parts were antiques, but the detection of various anachronisms pointed to manufacture in the age of the Hammer horror film, and somebody called Michael de Winter claimed to have produced kits, from 1972 onwards, to sell to fans of the genre.

A large number of these kits are supposed to be the work of a Professor Ernst Blomberg, with pistols supplied by a known Belgian gunsmith, Nicholas Plomdeur, exclusively (as far as I know) for the English market. Among other things, however, Professor Blomberg appears not to realize that a cross isn't the same thing as a crucifix. (Cut to our intrepid tourists trying to ward off Nosferatu: "well, you forgot to bring Our Saviour with you, but I'll let you off, just this once . . .". ) He also seems to be prescient in his knowledge that silver bullets can harm vampires – the first reference to this useful tip in print is in The Vampire: His kith and kin (1928) by Montague Summers.

It would be interesting to know if anybody has thoroughly analysed the language on the distinctive labels of these "Blomberg" vampire-killing kits; for example, they refer to the vampire as a "particular manifestation of evil", a phrase which an initial glance at Google N-gram suggests has gone, either side of Dracula, in and out of fashion. But maybe that would be excess to requirements. There doesn't seem to be any mention, in some Victorian gentleman's account of his travels, of setting out for foreign parts with his Baedeker and his Blomberg.

Still, collectors have paid impressive sums for such kits ("Stephanie Meyer clearly has a lot to answer for", as one sceptic has put it), and by those standards the Royal Armouries got a bargain when they acquired this one, which isn't a Blomberg, a couple of years ago, after it was left to a Yorkshire woman in her uncle's will. Greg Buzwell, one of the Terror and Wonder curators, points out, the components do appear to be "authentically Victorian in origin" (the Book of Common Prayer here is dated 1857) and the mystery surrounding the kit "adds to the allure" (that word again), even if it's most likely that the "huge popularity" of Hammer and Christopher Lee's Count Dracula were the immediate inspiration for somebody to enterprisingly cash in.

On the other hand: Jonathan Ferguson, the Armouries' curator of firearms, doesn't rule out the possibility that it's older than it appears, but has described this kit as probably an "invented artefact" of fairly recent origin. (Several points here come from his intriguing essay about the phenomenon of the vampire-killing kit in the Fortean Times, "To Kill a Vampire", April 15, 2012.)

That sounds about right to me. I think the stakes pictured above recalls some of Peter Cushing's most famous scenes rather than the "three feet long" vampire-impaler lugged around by Stoker's Van Helsing. The inclusion of a bottle for holy earth is also curious, since Stoker's Dracula, as Jonathan Harker reports, actually sleeps in "sacred earth". Perhaps it has some distant relationship with what the early American poet Joseph Rodman Drake mentioned in passing: "No gory vampyre taints our holy earth, / . . . Fair reason checks these monsters in their birth" ("To a friend").

In any case, I agree with Ferguson that it's a remarkable object and not exactly a "fake", since there's no proven "original" – cf. The Castle of Otranto? – and its presence certainly seemed to please people during the Terror and Wonder press view, as we retreated from the dark corner of the exhibition where F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu runs on its uncanny loop . . . .

With thanks to Greg Buzwell, Jonathan Ferguson and Evie Jeffreys.

October 3, 2014

Books unbound – and Prufrock in his cabinet

By MICHAEL CAINES

Whitechapel art gallery hosted the London Art Book Fair for the sixth year running last weekend, and a very fine affair it was too . . .

Whole tables of graphic novels from Canada stood next to delicate, bird-adorned matchboxes. Children’s books by Stefan Themerson, graced by Franciszka Themerson’s distinctive line drawings, lay next to the bright and bold London Jungle Book by Bhajju Shyam. The exhibitors, over two floors, included London galleries, art presses from across the Continent, academic presses (the MIT Press has done Marius Hentea’s TaTa Dada (about Tristan Tzara) and Branden Hookway’s Interface proud) and smaller-scale operations (I picked up a few issues of Mike Nicholson’s terrific seasonal “bio auto graphic”) – suggesting a thriving world of endless invention, diversity and abundance.

That’s books for you, art or no art, 560-odd years after Johannes Gutenberg printed his first poem.

In the light of this abundance of works in print, much of it but by no means all of it in familiar codex form, it was interesting to find, between floors, on the mezzanine level, a small exhibition courtesy of a publishing platform and a visual arts studio: Unbinding the Book. Its aim was to “push the boundaries of how books can be experienced, by evoking the storytelling properties of print and the way in which images evoke a narrative, whilst bringing to life the materiality, form and physicality that make books so alluring and different from their digital counterparts”.

This seems like a canny deployment of the word “alluring” to me. There were plenty of examples of the well-made book on traditional lines just downstairs, such as the new publication from Fitzcarraldo Editions, Memory Theatre by Simon Critchley, with its plain cover and typographical clarity. This kind of design does necessary work on behalf of a book’s author, making it easy to read and a pleasurable to carry around. The works on show in Unbinding the Book, meanwhile, illustrated how the fun of messing about with the physical format of books, crossing those apparent boundaries, can obscure or complicate the book’s conventional purpose as a vessel for the printed word.

There are, for example, words printed in Aymee Smith’s take on Craig Dworkin’s Reading the Illegible – a book about erasure and defacing the text – only they become increasingly illegible as you turn the pages as, via a process of copying onto acetate and cumulative scanned, the image of the first page merges with the next, and the next . . . and so on.

Or there’s the “book-radio” devised by Magz Hall, which looks like a hardback on life support – only the wires sticking out of it connect with a junkshop array of radios, out of which spout the words of Archbishop Frederick Du Vernet, the author of Spiritual Radio (published posthumously in 1925), who believed that radio waves could be the means of uniting his extensively scattered British Columbian flock in prayer. I wandered past it a couple of times, tuning in and out as the book read itself out.

Or there’s a third piece – in some ways the one that intrigued me most of all – Vince Koloski’s response to T. S. Eliot, “The Cabinet of J. Alfred Prufrock”:

Apart from anything else, I was intrigued because I couldn’t see any indication that Faber and the Eliot estate had granted permission for Koloski to reproduce the entire text of Eliot’s poem, as he had done here. In fact, Koloski publicly noted instead that permission wasn’t confirmed even as the work went on show; and the exhibition is meant to be going on to New York some time, so it's not an entirely academic matter. It would be a shame, I thought, if nobody else got to see the “Cabinet” as part of this exhibition – or maybe even in the context of some authorised celebration for “Prufrock” as it nears the centenary of its first publication in Poetry (Chicago), in June 1915. Fortunately for Koloski, the estate has now approved his work.

As part of Unbinding the Book at least, it offers the probably all too conventional pleasure of simply reading the poem in “unbound” form, from start to finish, but illuminated by hidden lights, with Prufrock-like accoutrements stowed behind the glass on which the text itself appears. Here's a neatly folded shirt fit for the "formulated" narrator, "pinned and wiggling on the wall", an array of stiff collars ("mounting firmly to my chin"), black braces that for some reason put me in mind of that the damned snickering Footman. . . .

In short: I don’t think a Blaise Cendrars aficionado, say, familiar with the “giant film strip” of La Prose du transssibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France, or anyone familiar with a copy of The Unfortunates by B. S. Johnson or the alluring experiments of other artists would keel over in shock at anything on display during the Art Book Fair. But there was plenty of memorable, striking work on display. Not least in that Cabinet of Eliotic curiosities.

Roll on the Small Publishers Fair . . . .

October 1, 2014

If buildings could talk

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“Hello. Lovely to see you. Yes you. I’m this building here, the Berlin Philharmonic. I’m fifty years old . . . .” We’re on top of a stegosaurus-like roof – or, rather, the camera is – and the building is speaking to us in a female voice with a German accent: “Buildings have more influence on the world than you let yourself think . . . ”. This is the first of six short films in Cathedrals of Culture, the most recent 3D-film project by Wim Wenders, which had its UK premiere at the Barbican last week.

Wenders and five other filmmakers have each chosen a landmark building (the Berlin Philharmonic; the National Library of Russia; Halden Prison, Norway; the Salk Institute, California; Oslo Opera House; and Centre Pompidou, Paris) and use film to uncover their “soul”; exploring what the buildings are like behind the scenes, after hours, why and how they were built, and their impact on people and cities.

It puts architecture, and 3D-filmmaking, centre stage. According to Wenders, the viewer is immersed “like never before into a place” and the buildings “speak for themselves”. In fact, it’s not such a new device – it reminded me of Old English poetry, where you’re hard pressed to find a text that doesn’t give a voice to an inanimate object.

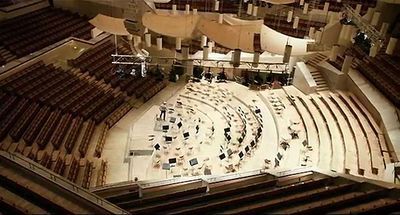

Wenders's take on the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall consists of extended panning shots fetishizing sections of the inside and outside of the building. Initially we are led by a child entering the space for the first time, then by one of its workers (a woman repairing the vibrant blue tiles on the tessellated floor of the entrance area, damaged by “women’s’ high heels”), then by Sir Simon Rattle (the orchestra’s principal conductor), and finally we follow the architect, Hans Scharoun (who died in 1972) – his bust morphs into a black and white hologram, with a cigar hanging characteristically from his lips.

Inside the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall

Inside the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall

After being banned from practising – he was labelled a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis – Scharoun designed the Philharmonic, the building tells us, as a “utopian image of society, for all walks of life” in a desolate part of West Berlin. It’s now the “beating heart” of the city’s culture district. The design is based on three interconnecting pentagrams, with the orchestra and conductor in the centre of the concert hall – which had never been done before; each audience member has an equal view, and every seat can be reached from every seat – there are no elite boxes. The space is cavernous, like an “ocean liner”, but feels festive and light like a circus tent.

A slightly sugary end (“I stand now in what has become a new city, a new country if you like”) moves us into the next film, created by Michael Glawogger about the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg. The camera takes us through shelves and shelves of battered bound books. And, as if acknowledging our presence, the overhead fluorescent lights flicker on as we pass. Overlapping voices, in both Russian and English, read extracts from texts, including Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Joseph Brodsky’s I Do Not Speak and St Augustine’s Confessions.

National Library of Russia, St Petersburg

National Library of Russia, St Petersburg

There are brief moments of comedy when Glawogger settles on librarians wearing dated green overall dresses: one monotonously stamps slips next to a wall covered in her pictures of cats. The film closes with a question about the future of the Library – the camera zooms into the screen of an e-reader left on a library desk and cuts to crowds of people and harsh-beeping traffic on the streets outside the building.

There’s a moving, at times troubling, portrait of Norway’s high-security prison, described as “the most humane in the world”; Robert Redford’s film explains the term “genius loci” – the subjective existential quality of a space – in relation to the Salk Institute designed by Louis I. Kahn; Oslo’s Opera House, which sits like a beautiful iceberg next to a fjord, asks us to “imprint [our] steps into my marble memory”; and Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ Centre Pompidou art gallery is presented as a “cultural machine” that shocked Paris out of its architectural sleep. “Even in darkness, empty of people, I’m full of sound.”

Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

As part of the Barbican's Constructing Worlds season, Cathedrals of Culture opened the cinema series exploring how film engages with buildings and urban life. The programme includes more well-known films (Woody Allen’s Manhattan; Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine; Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing), alongside essay films, documentaries, and newly restored silent films from the 1920s accompanied by live piano. There’s also a film about the brutalist Barbican complex itself from the directors Ila Beka and Louise Lemoine – they’re responsible for an excellent documentary series, Living Architectures, that lets us see the “real life” beauty of iconic, contemporary buildings (usually seen as formidable and detached from human contact).

Cathedrals of Culture does this, sometimes successfully, sometimes not (the entire film pushes three hours – there’s a limit, I discovered, to how much 3D your eyes can take before you feel nauseous). But Beka and Lemoine’s grounded reality is not really Wenders’s calling card. Think of Silver City (1968) – one of his early short films which is an extended shot of a Munich street as viewed from a window ledge, the only movement coming from cars and pedestrians – and the visual worship of buildings in Wings of Desire (1987). What we're asked to think about is the idea that buildings do speak to us – and we should let them.

September 30, 2014

Happy ITD!

By TOBY LICHTIG

Today is International Translation Day. Merry rendering one and all, and hats off to an often undervalued and generally underpaid profession. And why September 30? Ah, because today is also the feast of St Jerome and St Jerome is, informally at least, the patron saint of translators.

Born in today’s Croatia, around 347, Jerome studied Greek and Latin in Rome, and later Hebrew. Appointed papal secretary by Pope Damascus I, he was asked to provide a translation of the Gospels from Greek into Latin, and later translated the Old Testament from Hebrew into Latin, creating, in both versions, what came to be known as the Vulgate. He died in Bethlehem in 420.

International Translation Day was launched in 1991 by the International Federation of Translators (FIT) – a body that has been running since the 1950s. This year’s theme is “language rights”. “There is a wide range of situations in which human rights may be threatened if people are not able to exercise their language rights”, argues FIT’s President Dr Henry Liu in his message to mark the day.

“Think about immigrants, refugees, asylum-seekers, tourists and those working abroad. What happens if they fall ill and need to consult a medical specialist, unwittingly break a law, need to apply for social services or are involved in a dispute with an employer? How can they exercise their rights when they cannot even communicate their most basic needs and circumstances because they are forced to use a language they do not speak or write? This is where interpreters, translators and terminologists – all language professionals – play an essential role.”

Here at the TLS we like to think we do our bit for translators, and translations – especially those of a more literary nature. In this week’s edition – out on Friday – we will be publishing reviews of three novels in translation: Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami, which our reviewer, Ruth Scurr, declares to be the author’s “most tender” book since Norwegian Wood; F by Daniel Kehlmann, which is hailed by John Burnside as a “masterpiece” (not a word we tend to use too often in the TLS but one that certainly seems justified here); and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the third novel in Elena Ferrante’s acclaimed tetralogy about the friendship between two women from a poor neighbourhood in Naples (our critic, Christina Petrie, is not left disappointed).

Coming up over the next few weeks, we will also be publishing pieces on writers in translation including Andrés Neuman, Joan Sales, Gaito Gazdanov, Ippolito Nievo, Juan Marsé, Per Petterson, Jérôme Ferrari, Kamal ben Hameda, Eric Chevillard, André Gide and Irène Némirovsky.

But for now let’s raise a glass to the various translators who have made their books available in English and without whom the global delights of literature would be a very monochrome affair.

September 26, 2014

Houellebecq the actor

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Michel Houellebecq’s novels undoubtedly have a cinematic quality, and several of them have transferred to the screen: there was a decent attempt at his short first novel L’Extension du domaine de la lutte (1994, Whatever; why didn’t the translator of the novel go the whole hog and call it “Whatevs”?) I haven’t seen the film version of his finest novel Les Particules élémentaires (1998, Atomised), but recall that the film of the frankly not very good Possibilité d’une île (2005) was, as they say, universally panned. Plateforme (2001) and the Goncourt prizewinning La Carte et le territoire (2010) await cinematic treatment.

But it was only a matter of time before the author himself took to the silver screen. The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq,directed by Guillaume Nicloux, has him playing himself as the victim of an amateurish kidnap gang of three (one very large, the second a bodybuilder, the third a gentle hard man). While there is something curiously narcissistic about Houellebecq playing himself, he has already placed himself at the centre of his fiction: the best scene in The Map and the Territory involves the discovery of the mutilated body of one Michel Houellebecq. But it has to be said he is the very negation of the matinee idol; indeed there is something sleazy about his onscreen persona; the tics are all there: his curious way of holding a cigarette (and he’s nearly always smoking) between middle and ring finger, his anti-social habits, his terrible dress sense. He appears vulnerable and lost, at one point shuffling through a park holding a large plastic glass of lager.

There is really very little to this film: the author is taken from the brutal high-rise apartment he inhabits on the outskirts of Paris to an equally unprepossessing house an hour outside the city; he spends several days in captivity, is manacled, drinks a lot and has heated conversations about H. P. Lovecraft with his hosts. The fat kidnapper reads him a terrible poem he wrote as a 14-year-old and Houellebecq laughs uncontrollably. Later a local 21-year-old prostitute, Fatima (Marie Bourjala), comes to visit him twice and appears to develop an affection for him. We learn something of Fatima’s troubled family history.

Houellebecq doesn’t appear in a hurry to be released and no ransom is ever discussed, although when he is released after four days he asks, sceptically, whether President Hollande had a hand in his liberation, to be told no. Given its ostensible theme of kidnap and ransom, it was unfortunate that the French Institute’s brief screening of the film opened on the day it was announced that the 55-year-old French mountaineer Hervé Gourdel, who was kidnapped within a day of his arrival in Algeria, had been decapitated by Islamists, in retaliation for France’s involvement in Iraq and Syria.

It’s curious too that the film should receive official approval in the shape of a French Institute screening. For all Houellebecq’s talent as a novelist, I can’t help wondering whether the cultural authorities in France don’t find his public persona embarrassing.

But I did enjoy the closing shots of Houellebecq at the wheel of his spiv ransom-payer’s black Bentley automatic, going down the autoroute at 220 kph. He seemed to be enjoying himself too.

September 25, 2014

Lyly’s lunacy

Photo: Robert Piwko

By MICHAEL CAINES

The TLS recently moved from an office just north of the Thames to a newer one just south, near London Bridge. That made it easy for me, a couple of days ago, to stroll along the river to Shakespeare's Globe in the afternoon and its neighbour the Rose Playhouse in the evening – to see two plays that both happen to concern utopian dreams and (a more common coincidence) troubled relationships between men and women. As far as I can see, there’s only one more date when this accidental double bill is repeated.

I hope there'll be a word in the TLS soon about the first of those plays, Pitcairn at the Globe (it then goes on tour); because it's only running for another week, though, here's a word about The Woman in the Moon at the Rose. And the word is: goandseeitifyoucan.

First published in quarto in 1597, The Woman in the Moon is one of the lesser-known plays by that Elizabethan university wit and master of Euphuistic prose John Lyly – in fact, it’s his only play written in verse, and seems to have been a late, doomed attempt to adapt to changing political circumstances and theatrical fashions.

Lucy Munro, writing in the TLS a few years ago, called it “possibly the ultimate expression of Lyly’s interest in change and mutability”: at the centre of the action is Pandora, created by Nature, desired by four hapless shepherds in Utopia (the name is taken from Thomas More but not much else, I’d say), and envied by the seven planetary gods (Saturn, Jupiter, Sol etc), who take immediate umbrage against her and then take turns in exerting their generally baleful influence over her.

In addition, I suppose Lyly hoped the play would delight those who could recognize how The Woman in the Moon transmutes its basic materials; Pandora’s creation is a tale as old as Hesiod but astronomical notions of planetary deities shaping human affairs were very much on people’s minds in the sixteenth century.

Revivals of Lyly in general are extremely rare; in the case of this, his last play, possibly the most notable of the past century was at Bryn Mawr College, when Katharine Hepburn took the lead role. As Pandora in the production by The Dolphin’s Back at the Rose, Bella Heesom (above) shows that the part requires tremendous versatility and stamina. She is barely ever off-stage, and has to play the seductress (under Venus’s influence), the fighter (Mars), the trickster (Mercury) and so on. And while the gods get to stand back and watch – although, true to form, Jupiter prefers to test Pandora by throwing himself at her – the rest of the company has to follow suit.

As directed by James Wallace, the play is a farcical race from one mood to another, ninety minutes without a break, as the shepherds (below) fight and plot against one another, the planets’ influence over Pandora influencing their behaviour in turn. Nature’s beneficent vision of a “solace unto men” gives way to chaos as this “newfound god” has to choose a single partner.

Photo: Robert Piwko

In reading the play, I’d not seen how the efforts of Pandora’s servant Gunophilus (James Thorne, making like a young Lee Mack playing both Dromios) to keep up with his mistress’s demands constitute a hapless subplot, culminating in him coming tantalizingly close to running off with her, only to be defeated by the latest in her sudden shifts of mood, as the changeable goddess Luna takes over.

In fact, with the period’s usual dismaying complacence about these matters, it’s Luna with whom Pandora chooses to remain at the end of the play, enjoying the fact that she made her “idle, mutable, / Forgetful, foolish, fickle, frantic, mad”. It is the inconstant moon goddess who can make the mutability of the past five acts a permanent state of affairs. “These be the humours that content me best.” A modern audience has to lump it, I guess, even if they don’t like it.

For its next trick, Wallace’s company revives another rarity, Marlowe’s Massacre at Paris, at the same venue (which, incidentally, is in need of either the general public or a magnate with taste and £5 million at his or her disposal, to transmute its own future). It reminded me that although this has been an exceptionally good year for admirable revivals of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, there are still plenty of thoroughly stage-worthy pieces that seldom get anywhere near a stage. Lyly’s lunacy, for example, only needs a strong ensemble, clear verse speaking, distinctive costumes and a small budget . . . .

What price a Ben Jonson season on a similar scale? At the launch of the Cambridge Ben Jonson edition a while ago, a friend of mine asked the three general editors on the podium which plays they’d like to see revived. There were a couple of more obvious choices, but one of them went for The Magnetic Lady, a late, allegorical, seemingly unsuccessful play that modern theatre companies and theatre historians have generally ignored. Just like The Woman in the Moon . . . Any other suggestions, dream seasons, fantasies of Caroline drama coming back into fashion – for the first time since the early 1640s?

September 24, 2014

Cellar door – and other euphonies

Photograph from Grant Street Woodworking Co

By DAVID COLLARD

My recent blog on word aversion – an irrational loathing of words that are not in themselves offensive or disgusting – attracted some striking examples from TLS readers of their own particular hatreds, including “pelmet”, “Nicaragua” and the phrase “return to form”. But what about words and phrases that are objectively attractive?

There is a charming branch of linguistics called phonoaesthetics – the study of the intrinsic pleasantness (euphony) or unpleasantness (cacophony) of the sound of certain words, phrases and sentences – and the English compound noun “cellar door” has long been cited by phonoaesteticians as an example of a word or phrase that is beautiful purely in terms of its sound and regardless of any meaning. That is to say foreign speakers with no knowledge of English whatsoever nevertheless recognize something intrinsically attractive in this three-syllable sequence of phonemes, from the sibilant “c” in “cellar” to the very lovely diphthong in “door”.

Cellar door. Cellar door.

An article in the New York Times (February 11, 2010) cited the novel Gee-Boy (1903) by Cyrus Lauron Hooper as the first written mention of “cellar door”’s particular allure. Of the novel’s main character the author writes:

“He even grew to like sounds unassociated with their meaning, and once made a list of the words he loved most, as doubloon, squadron, thatch, fanfare (he never did know the meaning of this one), Sphinx, pimpernel, Caliban, Setebos, Carib, susurro, torquet, Jungfrau. He was laughed at by a friend, but logic was his as well as sentiment; an Italian savant maintained that the most beautiful combination of English sounds was cellar-door; no association of ideas here to help out! sensuous impression merely! the cellar-door is purely American.”

Purely American? Mneh. And one has to point out that many of the words in this list aren’t English in the first place, begging the question: what are the equivalents, in other languages of “cellar door” to English speakers? The poet Michael Rosen opts for “libellule”*, the French word for dragonfly, and it would be interesting to put this to the test with a group of non-francophones (from which, alas, he would be excluded).

But to return to “cellar door”, which causes all kinds of nice things to happen to the lips, tongue and palate when it is uttered. I wonder if part of its appeal is down to the ghostly presences it contains: the homophone “adore”, or a whiff of the French “c’est la”. (This gallic echo reminds me of the 1970s BBC television presenter Larry Grayson whose catchphrase “Shut that door!” reportedly derived from his attempts to say “je t’adore”. “Cellar door” was also the inspiration behind the name of the television production company Celador, responsible for such popular entertainments as Who Wants to be a Millionaire?)

In 1935 the drama critic George Jean Nathan used the euphonious phrase to put the boot into Gertrude Stein:

“Sell a cellar, door a cellar, sell a cellar cellar-door, door adore, adore a door, selling cellar, door a cellar, cellar cellar-door. There is damned little meaning and less sense in such a sentence, but there is, unless my tonal balance is askew, twice more rhythm and twice more lovely sound in it than in anything, equally idiotic, that Miss Gertrude ever confected.”

What, one wonders, was Gertrude Stein’s favourite word or phrase? Henry James plumped for “summer afternoon”. Dylan Thomas opted for “helicopter”. In a recent Guardian poll at the Edinburgh Book Festival, Tim Lott admired “mnemonic”, Ann Widdecombe “rodomontade” and Neil Gaiman “ineffable”. Alasdair Gray’s choice was “plakkopytrixophylisperambulantiobatrix” (the title of an unfinished poem by G. K. Chesterton).

Cellar door? Helicopter? Summer afternoon? For me there is no contest.

* In the original version of this piece “libellule” was misspelled as “libellue”

September 22, 2014

Life, a user's manuals

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Toothbrushes:

Brins finement arrondis: respect des dents et des gencives

Cordas con puntas redondeadas: respetan los dientes y las encías

Cerdas em Tynex com extremidade arredondada: respeitam os dentes e as gengivas

Finely rounded bristles: respect of teeth and gums

Setole finemente arrotondate: rispetto dei denti e delle gengive

Leicht abgerundete Borsten: Schutz von Zähnen und Zahnfleisch

Fijn afgeronde haren: beter voor tanden en tandvlees

Dental floss:

Helps to reduce gum problems and tooth decay by removing plaque between the teeth and the gums. Slides easily between teeth without shredding.

Aide à réduire les problèmes de gencives et l’apparition de caries en enlevant la plaque présente entre les dents et entre les dents et les gencives. Glisse facilement entre les dents sans s’effilocher.

Entfernt Plaque in den Zahnzwischenräumen und unter dem Zahnfleischrand und hilft so, Zahnfleischprobleme sowie Zahnhalskaries vorzubeugen. Gleitet sanft zwischen den Zähnen ohne auszufransen.

Shaving cream:

Wash face and leave wet. Apply . . . with wet brush and work up lather.

Humedezca la cara y aplique la crema . . . por medio de una brocha generando abundante espuma.

Humedeça a cara e aplique o Creme de Barbear . . . com um pincel da barba até fazer espuma suficiente.

Dog toys:

Fun, interactive shake, stretch and squeak toy. Minimal stuffing for minimal mess [not true] . . . . Not a chew toy!

Lustiges, interaktives Quietschspielzeug für Zerr- und Schüttelspiele. Minimale Füllung für minimalen Schmutz . . . . Kein Kauspielzeug!

Jouet amusant et couinant, à secouer et étirer. Rembourrage minimal pour un désordre minimal . . . . Pas un jouet à mâcher!

Un juguete divertido e interactivo para agitar y estirar, que además suena. Míniño relleno, más limpieza . . . . ¡No es un juguete que masticar!

Divertente gioco interattivo: si può agitare, allungare ed emette squittio. Minima imbottitura per minimo disordine . . . . Non è gioco da masticare!

Light bulbs:

Dimmable – Warm white

Dimmbar – Warmweiss

Dimbaar – Warm wit

Variable – Blanc chaud

Intensità regolabile – Luce calda

Regulable – Luz cálida

Com regulação de intensidade – Branco quente

Dimmabil – Alb cald

Var lietot ar gaismas regulatoru – Silti blats

Stmívatelná – Teplá bílá

Bin liners:

Tailor made – invisible when the lid is closed

Fait sur mesure – invisible quand le couvercle est fermé

Massgeschneidert – unsichtbar bei geschlossenen Deckel

Fatto su misura – invisibile con il coperchio chiuso

Hechas a medida – invisibles cuando la tapa està fechada

Feito à medida – invisível quando a tampa está fechada

Op maat gemaakt – ‘onzichtbaar als de deksel dicht is

Not sure what this one is:

Smart coding

Code astucieux

Clevere Codierung

Codice colorato

Códigos ‘inteligentes’

Codificação inteligente

Slimme codering

Water clocks:

Comment nettoyer les electrodes?

Reinigung und Regeneration der Elektroden

Hoe u de interne electroden kunt reinigen

How to clean & rejuvenate the electrodes

Product registration:

Maximize your . . . experience by registering your product

Elargissez votre expérience . . . en enregistrant votre produit

Verhoog uw beleving door uw product te registreren

Fai unica la tua esperienza con . . . registrando il tuo prodotto [a bit informal!]

Aumente a sua experiência . . . registrando o seu produto

Du kan registrera din . . . produkt för att få maximal upplevelse

Aumente aún más su experiencia . . . registrando su producto

Steigern Sie Ihr . . . Erlebnis indem Sie Ihr Produkt registrieren

Få en optimal . . . -oplevelse ved at registrere deres produkt

Or

Don’t forget to register your new purchase online.

N’oubliez pas d’enregistrer votre nouveau produit en ligne.

Vergessen Sie nicht, Ihr neues Produkt online zu registrieren.

No olvide registrar online su nueva adquisición.

Non dimenticate di registrare on-line il vostro nuovo acquisto.

Vergeet niet uw nieuwe aankoop online te registreren.

Não se esqueça de registar o seu novo produto online.

Ne feledje regisztrálni új keszülékét!

Nu ulta să-ți înregistrezi online noile achiziții.

Dog food:

Complete feed for dogs – Specially for adult and mature Dachshunds

Aliment complet pour chien Teckel adulte et mature (that last word’s not right!)

Alleinfuttermittel für Hunde – Speziell für ausgewachsene und ältere Dackel

Washing-up gloves:

Usage: In order to maintain performance over time, we advise you to: Enforce proper hygiene . . .

Utilisation: Nous vous conseillons, afin que ces performances soient maintenues dans le temps:

D’observer une parfaite hygiène . . .

Uso: Per conservare nel tempo le prestazioni del prodotto, consigliamo di: seguire una perfetta igiene . . .

Gebruik: Om de prestaties van dit product voor lange tijd optimal te houden, raden wij u aan: een

maximale hygiëne te betrachten . . .

Ink:

Tintenpatronen

Ink cartridges

Cartouches d’encre

Inktpatronen

Cartuccio d’inchiostro

Cartuchos de tinta

Batteries:

Achtung: Die Batterie darf nicht geöffnet werden.

Avvertenze: Inserire correttamente, non ricaricare, non gettare nel fuoco, non aprire, . . .

Attention: Respecter les polarités (+/-), ne pas recharger, ne pas jeter les piles au feu ni les ouvrir, . . .

Warning: Insert correctly (+/-), do not recharge, do not open or dispose in fire, . . .

Atencion: Respetar las polaridades (+/-). No rescargar ni abrir las pilas. No arrojarlas al fuego.

Atenção: Utilizar correctamente (+/-), não recarregar, não abrir as pilhas, não atirar ao fogo, . . .

Waarschuwing: Een batterij nooit openen of in het vuur werpen, niet herladen, . . .

White wine:

Fresco y brillante. Aromas a flor di albaricoque y cítricos. Cuerpo y juventud equilibrados

Fresc i brillant. Aromes a flor d’albercoc i cítrics. Cos i joventut equilibrats

Contains sulfites

Contiene sulfitos

Conté sulfits

Enthält Sulfite

Have I left anything out?

Oh yes, the

French bean slicer:

Strings and slices in one easy action!

Effileur de type français pour haricots – Effile et tranche en un mouvement facile

Cortadora de habichuelas estilo francés – Taja y troza en una acción rápida y fácil

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers