Peter Stothard's Blog, page 42

June 24, 2014

War, illustrated

By TOBY LICHTIG

One of the most frequently lamented, and lampooned, aspects of modern media saturation is the dulling of the audience's response, even to the most terrible situations. We all know how a newspaper report on the latest Syrian refugee crisis begins, or what a broadcast from the heart of the warzone looks like. Even new and extraordinary images and accounts can swiftly become simulacra, as Jean Baudrillard warned us over two decades ago when considering the First Iraq War. These ideas are now so widely discussed as to be clichés in themselves. And yet sometimes it is possible to tell the story differently.

Last Friday I attended a remarkable event at the V&A which showcased two unusual approaches to war reporting, standing somewhere at the crossroads of art and journalism. The evening was staged in conjunction with Refugee Week and focused on what contemporary journalistic convention would have us describe as "the ongoing humanitarian disaster in Syria".

The first exhibit – "Project Syria" by Nonny de la Peña – was an exercise in what its creator calls "immersive journalism". The installation, originally commissioned by the World Economic Forum, employs virtual reality based on real events to put the viewer "on scene". Given a headset and headphones you are invited to wander around a delineated rectangle (about the size of a small bedroom) as events play out before your eyes in real time. As you walk within the rectangle, you walk within the simulation, taking in the alarmingly lifelike sights and sounds.

Initially, I found myself on a quiet street in Aleppo. There were a few pedestrians, parked cars, a café; a distant sound of chatter and traffic, the natural thrum of city life. Then, shockingly, a bomb exploded. Fear and chaos choked the air. As the smoke cleared, I could see an injured man lying to my left, people running amid the blare of sirens. The scene then faded to reveal a refugee camp, rows of tents fanning out in all directions. Their denizens appeared ghostlike before me. The atmosphere was calm but muted, the sense of hopelessness palpable. A narrator in my earphones then provided her report.

De la Peña's exhibit engages directly with our voyeurism. Our sense of agency here is disquieting (we are more used to being passive news consumers) and yet it has its limits (we are still cordoned off, prevented from straying outside the rectangle by a firm hand here and there). The message is hardly subtle and part of the installation's impact is no doubt down to its novelty, but it was nevertheless affecting. It certainly made me think more deeply about the experience of being in a warzone – and the way I engage with the media describing it.

The second "reporter" used a rather more traditional technique which, in its very old-fashionedness, also made me reassess my relationship with contemporary media.

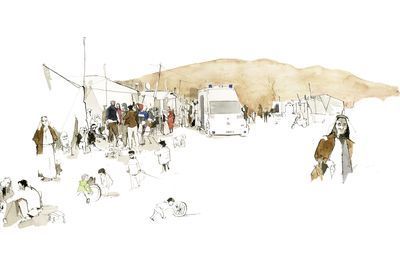

George Butler is an illustrator who works in pen, ink and watercolour. He specializes in current affairs, drawing in situ. I'd already seen some of his portraits of the Syrian conflict at a talk he gave earlier this year and was struck by their jarring beauty, once again so different from the "usual" run of news images. It has been a century since John Singer Sargent was commissioned by the British Ministry of Information to depict the battlefields of Europe but Butler's work shows that the medium still has much to give to journalism. Various media outlets agree: Butler's pictures have been featured by, among others, the BBC and the Guardian.

Butler's mini exhibition of new works, "Syria: Stories of devastation and hope", was staged in conjunction with Doctors of the World and introduced by Lord Rogers, one of the charity's trustees. The artworks were the result of eight days Butler spent earlier this year in various refugee camps in the Bekaa Valley in northern Lebanon.

Some focused on the possessions people took with them:

The arbitrary assortment of items, including that bathetic television remote control (the television being left behind) attest to the haste and confusion that marked the start of exile. "The objects were things they grabbed when the lights went off", said Butler afterwards.

There were some wonderful individual portraits, including this one of a lady called Moun, the tattoos on her face a remainder of the decorations of her youth:

This picture is of a boy called Khalid, who was born six months into the war:

Khalid appears once again, rolling around his broken bicycle wheel, in the picture below, which portrays the weekly visit of a mobile medical unit to a camp in Kamed el-Loz:

Much of the power of Butler's illustrations is wrought by absences, the blank or spare backgrounds seeming to attest to communities denied a complete human experience:

The illustration above dates from Butler's first visit to Syria. It was one of the first scenes he encountered after crossing the border, the vibrancy of the children playing on the tank standing in disarming contrast to the leeched-out destruction behind them.

One of Butler's chief assets is the trust his approach allows him to establish. The illustrations take time (generally at least a couple of hours) and require a certain level of intimacy. He talks about how his subjects tend to find the instruments of brush and paint less intrusive than camera lenses.

Butler also spoke movingly about the shift in attitudes he encountered between his two visits to the region. "When I first arrived in northern Syria the general view was Assad must go. When I returned two years later this had changed. It was now: We don't care who rules as long as we can go home."

Two of the illustrations are currently up for auction via Doctors of the World (closing at 5pm on Wednesday June 25) at a reserve price of £1,250 each. All of the proceeds go to the charity. If the reserve price isn't met, they will be reauctioned in October.

June 18, 2014

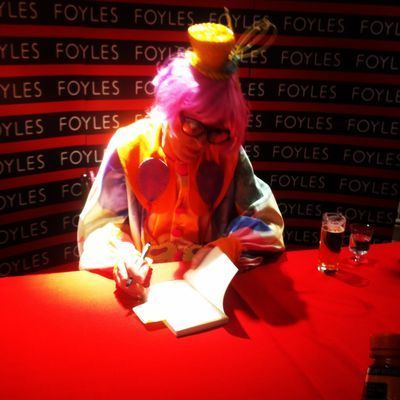

Grayson Perry at Foyles

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Is there anyone in the art world more instantly likeable than Grayson Perry? He seemed to fill the room with good cheer as soon as he crossed the threshold (or emerged from the green room) of Foyles bookshop on Monday evening, resplendent in clown garb accessorized with an umbrella and a pink wig.

He was there to open the Art department of Foyles’s new flagship shop – 107 Charing Cross Road, next door to the old one – and he began by telling us that he once shared a high-class squat with a really good shoplifter. Foyles was deemed easy pickings in those days, he said, and this man was a regular. He was eventually caught holding a bulging bag, and he subsequently found (the shoplifter, that is) that he was more embarrassed by the pretentiousness of the books – the titles were read out in court, I think Perry said – than by the crime itself.

Perry declared his belief that art books, as appealing objects, are one part of the book trade that "won’t die out soon”. He was reminded of an anecdote about Lord Snowdon, who having published a book containing pictures of artists’ studios, gave a copy to the Queen, prompting the response, “I really must get a coffee table”. There is another intrinsic merit in the hard-copy format: its (relative) durability – you don’t want to spill turpentine on your iPad. Perry’s books have survived the studio, even if some of them are a bit “sepia-tinted” in places.

The publication of a monograph is a great moment for an artist, Perry said. When he had his first show, he was more excited about the catalogue – at least at the moment when somebody came along and held it up – than about the actual exhibition. For him a catalogue is a “multi-coloured tombstone”. But in the art book sector in general, he said, “there’s a lot of umming and ahing”. Art books can be expensive and difficult to produce. And it can be difficult for the consumer, too. How do you know what to buy?

Perry provided – with the authority of somebody confident in such matters (“Artists: we trust our own subjective experience”) and who buys a lot of art books – a suggested decision-making procedure:

1) Are there enough pictures?

2) Are they good pictures?

3) Are there enough pictures you haven’t seen before?

4) Proceed to checkout.

A Foyles representative then began the countdown – "10, 9, 8 . . .”. Perry had been given a pair of scissors, and he stabbed the air with every number. Then he cut the ribbon, and the book-signing could begin.

The Foyles Grand Opening Festival runs until July 5 (the Editor of the TLS, Peter Stothard, and Mary Beard, Classics editor, will be appearing next Thursday; unfortunately tickets for their event Confronting the Classics have sold out, but some events have spaces available: the full programme can be found here).

June 16, 2014

Alexander Pope: A poet in marble

Photo: M. Caines

By MICHAEL CAINES

One day in March 1742, the aspiring artist Joshua Reynolds, not yet twenty years old, was attending an auction in Covent Garden, when the crowd parted and somebody both very great and very small walked in: the poet Alexander Pope.

Reynolds remembered him as being “about four feet six high; very humpbacked and deformed; he wore a black coat; and according to the fashion of that time, had on a little sword”. By that point in his life, only a couple of years before his death, Pope, a victim of Pott’s disease, would probably have been wearing a corset to support his weak, crooked spine, and he only rarely appeared in public. Perhaps the most striking thing about Pope, though, apart from his stunted height and the fact that everybody (“by a kind of enthusiastic impulse”, according to Boswell’s version of Reynolds’s anecdote) wanted to bow to him or shake his hand (depending on which source you prefer), was his face. Understandably, Reynolds, the future portrait-painter to the elite, thought it an extremely interesting one:

“[Pope] had a large and very fine eye, and a long handsome nose; his mouth had those peculiar marks which always are found in the mouths of crooked persons; and the muscles which run across the cheek were so strongly marked as to appear like small cords.”

Boswell goes characteristically further: Pope had a “pallid, studious look; not merely a sharp, keen countenance, but something grand, like Cicero’s”.

This was the same “countenance” that the sculptor Louis François Roubiliac saw, of a man who “had been much afflicted with headache”. Roubiliac claimed that he “should have known the fact from the contracted appearance of the skin between his eyebrows, though he had not been otherwise apprised of it”.

The damaged body did not prevent Pope from becoming one of the most frequently depicted of all eighteenth-century figures. He sat almost eighty times in total for dozens of artists, who flatteringly portrayed him in paintings, engravings and sculpture (while others, in caricature, were less kind). Jonathan Richardson went so far as to portray him wreathed with bay leaves in profile, as a modern literary head fit for an antique coin. The image is a fitting one for a translator of Homer and imitator of Horace:

Books on display from the Waddesdon Collection with a portrait of Alexander Pope, c 1737 by Jonathan Richardson hanging above. On loan from the National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: © Richard Bryant/arcaidimages.com

This is in keeping with Pope's far-reaching influence on eighteenth-century culture, not only as a poet but as an authoritative, respectable artist-intellectual: an editor of Shakespeare (whose edition distinguishes typographically between good passages and bad), a cultivator of his own remarkable "grassplot" at Twickenham, a proponent of the dangerous idea of philosophical optimism ("Whatever IS, is RIGHT", according to An Essay on Man). At the same time, Pope excelled at making enemies who didn't hold back in contradicting the dignified image he was so keen to cultivate.

Yet there is more to the artistic flattery than merely the taking of one artistic side over the other. The painters Charles Jervas (with whom Pope briefly lived and studied painting) and Sir Godfrey Kneller both emphasize the poet's large eyes and slender hands rather than anything else that the sitter would obviously have found distressing – but to markedly different effects.

Over the course of the century, two interdependent tendencies in Pope portraiture emerged from a division latent in his public persona. There is the sublime visionary who wrote the Moral Essays and An Essay on Man (“What would this Man? Now upward will he soar . . .”); and there is the satirical gentleman, the scourge of folly, the man of sense and wit who produced The Dunciad and had the epigrammatic wit to engrave the collar of the puppy he gave to Frederick, Prince of Wales: “I am his Highness’ dog at Kew; / Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you?”

Both are Pope, although perhaps today we tend to think of the wit more than the visionary. William Blake, though no great fan of Pope, could at least give the visionary some credit, and, working on a commission, portrayed him, in the words of the literary scholar Wallace Jackson, with “head tilted upward, eyes more or less looking inward, hand on the side of the head, and hair swept backward as though by a divinely caressing wind”. To one side stands a female figure whom I reckon, from the “moon-light shade” and “visionary sword”, to be the subject by Pope’s “Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady”, with the praying Eloisa of Pope’s celebrated Eloisa to Abelard to the other. For all that Blake spoke harshly of Pope’s “Metaphysical Jargon of Rhyming”, it is tempting to look through Eloise and suspect that something proto-Blakean lurks in lines such as:

“From the false world in early youth they fled,

By thee to mountains, wilds, and deserts led.

You rais’d these hallow’d walls; the desert smil’d,

And Paradise was open’d in the Wild.”

Did it matter what visual image people had of the poet they so ardently loved or hated? (Does it matter if we can picture Jane Austen as a girl or Jane Austen posing with the tools of her trade? Or to see what Jacob Epstein saw in his literary contemporaries?) Clearly, one of the crucial figures in the long-term evolution of the image of the poet was Roubiliac, and, as mentioned already, his image of Pope was an image taken from life.

The sculptor had taken a good, long look at Pope in a professional capacity, as he set about producing a series of striking portrait busts of the poet around the time of that Covent Garden auction. Pope sat for him in 1738, and Roubiliac produced at least four busts over the next three years, probably for Pope’s friends – all are inscribed ad vivum (ie, “from the life”, a reassuring formulation more usually seen on portrait engravings). More were to appear after Pope’s death in 1744 (or at least to remain in the sculptor’s studio until they found a buyer, as he seems to have kept a variety of his works on display as a kind of portfolio in marble; Roubiliac himself died in 1762), and variants on Roubiliac’s theme were to become commonplace.

Angelica Kauffmann, for example, as Pat Rogers notes in The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, seems to have had Roubiliac in mind when she designed “The Muses Crowning the Bust of Pope”. A plinth raises the poet so high that the muse brandishing the laurel wreath has to both find a foothold on the plinth’s base and raise her arms above her head – while turning her head adoringly to where a second muse kneels, poring over the collected works.

That question of height is a significant one in relation to Roubiliac’s portrait busts as well as depictions of Pope in general. A few years ago, at the Huntington Library, I heard Professor Malcolm Baker of the University of California, Riverside arguing that Roubiliac used the portrait bust to engage the viewer more intimately than did his classical predecessors – Roubiliac’s, that is, were not heads to be elevated far above our own, at the level of, say, the tops of the library shelves, but to be seen close up, contemplated in the context of a modern sense of selfhood.

A few days ago, in the company of the press and various sculpted Popes in marble, terracotta and plaster, I had the pleasure of meeting Professor Baker again. The venue was at Waddesdon Manor, near Aylesbury, during the press view for a remarkable exhibition he has curated, Fame and Friendship: Pope, Roubiliac and the portrait bust. Putting it together has clearly been, if nothing else, quite a feat of loan logistics. The eminent W. K. Wimsatt managed to bring together six of Roubiliac’s busts for an exhibition in 1961; as Baker gleefully pointed out, Fame and Friendship manages two more.

Fame and Friendship comes to Waddesdon after three months at the Yale Center for British Art, and has gained what Professor Baker calls a “French tweak” (casting a sidelight on Pope’s reputation in France) and lost a little of its American lilt (a Yale-centric emphasis on Wimsatt’s contribution the study of the Pope and eighteenth-century literature).

Otherwise, this collaboration between the two institutions differs primarily in now occupying an exhibition space with its own distinctive history, and one which has some fresh relevance to Pope’s own relationships with the rich and powerful. Imagine him and Roubiliac transported to the end of the nineteenth century: would they have been the kind of artists to be patronized by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, who built Waddesdon both to “display his outstanding collection of art and entertain the fashionable world”, as the visitor’s guide puts it? Or (and?) would Pope have gone away and composed a “Letter to Bethmann”, full of sniggering disdain for what he had seen there?

Transport Pope a century forwards again, to the present day: if he’d got past the current Waddesdon exhibitions of eighteenth-century court ceremonies and the intriguing Lod mosaic (in which giant fish threaten merchant ships and tigers mix with giraffes and elephants but the customary, tell-tale deities and signs of human life, the ships aside, are entirely absent), he would have found, upstairs in the faux-coco château itself, himself. Two rooms of himself, in fact, and mostly in the image that he liked to project.

In the first room, the elegant visions of Jervas and Kneller hang next to Jean Baptiste Van Loo’s larger portrait of the poet as a man either nursing one of those headaches noted by Roubiliac or embroiled in a visionary composition – his elbow again rests on Homer, and the fingers are again pressed to one temple, while the other clutches a manuscript.

Pope liked Jervas’s straight-backed “man of sense” (Wallace Jackson again) enough to use as the basis for the frontispiece engraving to his Works of 1717. Unlike this full-wigged, publicly presentable young gentleman, Kneller’s Pope has a more melancholy air, reflecting the circumstances of the commission – the death of an aristocratic friend and patron – and wears a distant, distracted look. One absent-minded elbow rests on a thick volume that happens to be labelled “HOMER”. The label is the same vivid vermillion as the poet’s headgear, colour-coding the precious classical connection for us. It’s the epitome, for the time, of a man with his mind on higher things.

Opposite is Roubiliac posing with his model of a full-length stature of Shakespeare, while beneath the canvasses are display cases of books, manuscripts and other items that generally prepare you for the purely sculpted experience of the portrait busts in the second room.

Stepping from the red ante room to the white drawing room ought to feel like joining the party at last: here are the guests of honour, albeit all of them turned to stone, and several of them being the same person. We are invited nonetheless to get closer to them, to pay close attention to them as they lean forward, gaze on the crowd, bend to attend to what little gossip we have to relay – or seem to look past us, on to another world. We can see those “small cords” Reynolds noted in Pope’s cheeks, the furrowed brow, even the wrinkles.

And if you’re in the eavesdropping mood, there is conversation of a sort to be heard, too. In one corner, Pope and Laurence Sterne (as sculpted by Joseph Nollekens, c. 1770) discuss literary fame and maybe the tribulations of the literary marketplace:

Photo: M. Caines

In another, Pope and his exalted Isaac Newton fail to catch one another’s eye:

Photo: M. Caines

And commanding the centre of the room are a number of Popes placed at a muse-friendly height, all of them Roubiliac’s, and each with its own slightly different mood. That owned by David Garrick, for instance, has fuller lips and less of a twist to the neck than most of others, and appears more stubbornly Roman, perhaps because the eyes are not incised, as the majority are. Another marble bust of 1741 has more of a twist to the neck and more of an upward glance, its attention caught by some overheard piece of folly that will later make its way into the Dunciad.

Taken together, they seem to vindicate Malcolm Baker's sense of an inwardness on display in Roubiliac's work – a vision of Pope as visionary, looking off into his realm of verse, both perceiving and creating order where, to others, there might appear to be none. No wonder Michael Rysbrack’s more foppish, Jervas-lite Pope of 1730, condemned here to the status of a baroque wallflower, looks uncomfortably like he might have crashed the wrong party.

In general, the panels accompanying these exhibits offer strikingly little in the way of quotation from Pope’s poetry – is it taken for granted that every visitor will know why anybody should have cared about him at all? Or perhaps the couplets would have distracted us from the crucial relationship between the poet and the sculptor. . . . It’s interesting to learn here, though, that the intensity of Roubiliac's terracotta model of Pope's head caught the eye of Elizabeth Barrett Browning who, although it doesn’t say so in the exhibition catalogue when it quotes her, would have known something of how it felt to be “drawn with disease and bitter thoughts”; she found the bust “a too expressive, miserable face . . . and very painful, I felt, to look at”.

The dissenting voice of Pope’s enemies can barely creep among this distinguished company, but it is certainly there in Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin’s watercolour and pencil send-up of the poet as a Peeping Tom in his subversive Livre de Caricatures tant Bonnes que mauvaises. London produced plenty of sordid and explicit etchings against Pope, such as those inspired by a story vengefully put about by Colley Cibber after Pope had made him the Arch-Dunce of the Dunciad, with titles such as “The Poetical Tom-Titt perch’d upon the Mount of Love” – but it has been prudently decided to leave such dubious pleasures for another occasion.

The portrait bust is, after all, a much weightier genre; the exhibition’s title, Fame and Friendship, points to its double significance for Pope’s reputation then and now. Rysbrack and Roubiliac alike were commissioned to provide busts for the homes of Pope’s friends or affluent admirers such as Garrick. These private emblems of friendship would also serve, however, as the basis for all kinds of public imitations – prints, engravings, enamelled Staffordshire earthenware. They represent both a web of close allegiances with loyal friends and the way Pope intended his image to stake its own powerful claim to fame.

June 13, 2014

Buried under books: the TLS office

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Here at the TLS we receive what seems like a huge number of books every week. The photo above shows the office a few days ago (we have been very short-staffed for one reason or another, and that hasn’t helped the book-sifting process). It sometimes feels possible that a member of staff will suffer the same fate as E. M. Forster’s Leonard Bast in Howards End: “Books fell over him in a shower.” We probably review about 5 per cent – if that – of the books sent to us. It’s consequently quite a challenge when publishers, agents or authors contact us to ask us if we have received a particular book – and if so, whether we will be reviewing it. May we get back to you?

Among the most bulky books that come in are in a series called the Oxford Handbooks (published by Oxford University Press, obviously). Generally weighing in at around a thousand pages, and with numerous contributors, they sell for around £100. The books are clearly immense works of scholarship, or industry. As the rubric on the dust jacket states, “The Oxford Handbooks series is a major new initiative in academic publishing. Each volume offers a state-of-the-art survey of current thinking and research in a particular subject area . . . . Oxford Handbooks provide scholars and graduate students with compelling new perspectives upon a wide range of subjects in the humanities and social sciences”. The covers are handsomely designed and the hardback spines feel solid; they’re heavy.

And OUP have been very busy: in recent months we have received the Oxford Handbook of Mobile Music Studies, Volumes I and 2, the Handbook of Propaganda Studies, the Handbook of State and Local Government (this one is actually in an American Politics series, but the format is the same), the Handbook of American Drama, . . . of Interactive Audio, . . . of Process Philosophy & Organization Studies (with a Cézanne cover image of Mont Sainte-Victoire), . . . of The Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers, . . . of Quaker Studies (edited by Stephen C.Angell and Pink Dandelion), . . . of Holinshed’s Chronicles, . . . of The American Revolution, . . . of Qualitative Research in American Music Education, . . . of Public Accountability, . . . of Religious Conversion, . . . of Political Leadership. Alas, none of them will be reviewed, worthy publications though they no doubt are.

But as if to further confound the notion that we are living in a bold new digital age, where books will become a relic of the past, we also receive countless books of the Focused Organization: How concentrating on a few key initiatives can dramatically improve strategy execution variety – not really our kind of thing even though we like to consider all disciplines from Anthropology to Zoology. Nor will we have space for Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space, or Ancestral Encounters in Highland Madagascar: Material signs and traces of the dead, or Arms Industry Transformation and Integration: The choices of East Central Europe, or Corporeality: Emergent consciousness within its spatial dimensions, or Cognitive Iconology. And I’m not sure there’ll be any takers for Transnationalizing the Public Sphere, or for Storyworlds Across Media: Toward a media-conscious narratology. (Authors published by American university presses seem keen on deploying the word “toward” in their titles, but do they ever get there?)

Then there are the quaintly specialized titles: Women and the Counter-Reformation in Early Modern Münster, The Science Fiction Dimensions of Salman Rushdie, Standing Apart: Mormon historical consciousness and the concept of apostasy, Gender Protest and Same-Sex Desire in Antebellum American Literature, Controlling Contested Spaces: Late antique Antioch and the spatial politics of religious controversy (the gerund noun is another favourite in titles).

We’ve tidied up the table a bit since the first photo (see below). But today’s haul hasn’t been sorted yet . . . .

As you can see, we are kept busy here. It’s a kind of battle of the books. And it often seems as though we’re losing. We're moving offices in September (for the fourth time in eight years), to smaller premises apparently. We're going to have to be ruthless.

June 12, 2014

World Cup fiction

By TOBY LICHTIG

One of the happier corollaries of a World Cup – away from the depressing corruption scandals, escalating costs, violent demonstrations, hideous tales of worker abuse, and aside from the actual football itself – is the chance it gives the world to scrutinize the host country, in all its cultural colours.

Those already bored by the endless books and documentaries about Brazilian history, politics, cookery and Amazonian derring-do may wish to stop reading this blog now, but despite a certain scepticism regarding the current Brazilian zeitgeist (are we to start ignoring the world's fifth largest country once the referee blows the final whistle on July 13th? Given the neglect South America is generally accorded by the British media, the answer is probably yes), I've enjoyed seeing the recent slew of Brazilian fiction in translation to have arrived on my desk at the TLS.

It all really began a couple of years ago when a selection of newly translated novels by Clarice Lispector was brought out by New Directions Press. Landeg White reviewed four of them for us, finding Lispector to be “a bafflingly elusive writer. But her images dazzle even when her meaning is most obscure, and when she is writing of what she despises she is lucidity itself”. Penguin Modern Classics is now reissuing several of these Lispector novels and the current edition of Music & Literature is partly dedicated to her, including a translation of her last interview, conducted a few months before her death in 1977. In the “Summer Books” special in the current edition of the TLS, Lispector is Alex Clark’s beach choice. “I am undaunted by reports of Lispector’s somewhat mystical style and suggestions that it is often hard to tell exactly what is going on in her work”, writes Clark. “What, after all, is summer for? And reading the story of a woman alone in Rio’s poorest neighbourhoods will be an interesting counterpoint to watching contemporary Rio on the television during the World Cup.”

Not long after the original New Directions Lispector translations, Granta dedicated its 121st issue to Brazil in a “best of young Brazilian novelists” special. Reviewing the collection for us in the Christmas issue of 2012, Brian Dillon was pleased to see that “some of the stories shine”, though he perceived a certain amount of Brazilian bandwagon-jumping in this “talent show”: “The Best of Young Brazilian Novelists is not a thrilling collection, betraying a lack of structural and stylistic ambition and a tendency towards sentimentality”.

But it was not until this year that the books from Brazil really began to arrive thick and fast, partly thanks to the Brazilian government, and its various cultural arms, which have been ploughing money into translation projects. (Dispiritingly enough, even this aspect of World Cup fever didn't escape a whiff of financial mismanagement. I was told by two different sources that publishers were having a hard time extracting the promised payment for their translators. The money had been delayed several months and people were getting agitated – though it is my understanding that matters have now been resolved.)

One of the trickier propositions has been rendering the playful and provocative prose of the experimental novelist (and poet) Hilda Hilst into English. Often compared to Lispector, Hilst was the heir to a lucrative coffee dynasty who rejected the polite society of her family in favour of São Paulo’s bohemia. Reviewing two new Hilst translations – With My Dog-Eyes and Letters from a Seducer – in the paper last month, Michael LaPointe delighted in a “joyfully wicked writer” and “a modern master of disturbance” whose characters “constantly rage against the strictures of language”. LaPointe drew particular attention to the translators, noting that Adam Morris (With My Dog-Eyes) “deserves the highest praise; the constant shifts in perspective call for tremendous agility. A typical passage of the novel will move from the third person to the first and back again, or else to a stranger perspective, in which [the protagonist] in the first person, observes himself in the third.” Meanwhile, John Keene (Letters from a Seducer) “must be applauded for the not insignificant feat of capturing Hilst’s countless slang words for genitalia”.

Alongside the experimentalism of Lispector and Hilst, I have also received a stack of thrillers – political, psychological, literary, crime – mostly set in Rio de Janeiro, including Hotel Brasil by Frei Betto, The Mystery of Rio by Alberto Mussa and His Own Man by Edgard Telles Ribeiro. Nick Caistor, one of our most prominent and prolific translators of literature from Portuguese, will be rounding up the current crop later next month.

But perhaps most exciting of all is the recent revival of Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1839–1908): a master of the short story who also wrote nine novels. Peter Robb, who writes about Machado de Assis in his superb book A Death in Brazil (which I highly recommend to anyone with an interest in the country, renewed or otherwise) will be writing a long piece on three newly translated collections of the author’s short stories, many of which have never before appeared in English. This review is unlikely to be published before the end of the World Cup, but I have faith that our readers – no slaves to the mode – will still have plenty of spare capacity for all things Brazilian long after the World Cup Trophy has been raised.

June 5, 2014

The Atlantic Wall

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

A compelling mini exhibition opened this week at the Royal Geographical Society entitled “The Atlantic Wall” (free, it runs until June 20 only).

“Hitler’s coastal fortress from the Arctic to the Pyrenees” is its subtitle and that of the short book by Ianthe Ruthven that accompanies it, including around one hundred staggeringly beautiful photographs of the bunkers, casemates or gun emplacements and observation posts that dot 3,000 miles of Atlantic coastline, from Kristiansand in Norway to Capbreton in Aquitaine. She doesn’t tell us what percentage those hundred photos represent of what survives – it would be interesting to know. But she has succeeded in transforming grim material into a work of art.

According to Ruthven, this “chain of World War II fortifications stretching from the Norwegian Arctic to France’s western frontier with Spain . . . is the least acknowledged of Europe’s historical monuments”. It was built between 1942 and 1945 and consumed 17 million cubic metres of concrete (construction was still going on right up to the end of the war); the work mainly done by forced labourers and prisoners of war – 300,000 were working on it at one point in 1944. Meanwhile “local contractors operating as subsidiaries of German companies benefited . . . the Wall is a monument to the profiteers of occupied Europe as well as to those who lived and died building it, or heroically breached its ramparts”. Some 8,000 bunkers were built in scarcely threatened Denmark alone. All of this was designed to repel the expected Allied invasion. Ruthven writes that “Albert Speer who took over the project after the death of Hitler’s chief architect Fritz Todt, recollected during his years in Spandau prison” that it “had been an exercise in futility”. As Ruthven writes, “in the absence of air supremacy, fixed defences were at best redundant, at worst useless”.

In a foreword the architectural historian and TLS contributor Joseph Rykwert talks of the “overwhelming, bare and void structures with which Hitler’s miscalculations littered the west of Europe . . . . They will stand as a lasting token of a mighty miscalculation”. Not the least part of the miscalculation was Hitler’s obsession with the idea of occupying British soil: 10 per cent of the materials were used up building fortifications on the Channel Islands (see below) that were never activated.

The impact of the photos is partly due to the way in which the fortifications have weathered: from the battery with snow-capped mountains as a backdrop in Norway to the bunkers in Capbreton that are now mostly underwater and that Ruthven has managed to capture with surfers bobbing like seals in the foreground and the Pyrenees in the distance beyond. Then there is the moss and lichen. (Sadly the photos available for reproduction here don’t quite convey the sheer beauty of Ruthven’s work.) In Denmark, “BunkerLove” festivals are held. Meanwhile anyone who has visited the Keroman U-boat base at Lorient in Brittany will have been awestruck by its sheer indestructibility. As Ruthven writes, “a 7.4 metres thick concrete roof proved impossible to penetrate despite the Allies dropping some 4,500 tons of bombs” (they destroyed the town instead). The base held out until the German surrender in May 1945.

In a jointly signed article in Le Monde on Monday, Sylvie Barot, the head conservator at the Municipal Archives in Le Havre, and Andrew Knapp, Professor of History at the University of Reading, point out that, while it is appropriate to pay homage to those who gave their lives on the beaches of Normandy, thought should be given too to the French civilians who lost their lives, possibly up to 2,500 on D-Day. 518,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on French soil – seven times as many as the Luftwaffe landed on British soil – causing around 57,000 civilian deaths. Continuing the stats: Le Havre received 10,000 tons of bombs in a week and was 85 per cent destroyed. Arthur “Bomber” Harris was later to regret that the near total destruction of the port that was intended to serve as a base for Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain did little to hamper the German war effort.

June 4, 2014

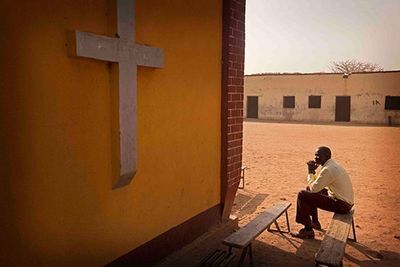

Seeing anti-Christian persecution for what it is

By RUPERT SHORTT

The battle for sexual equality clearly has a long way to run. But this doesn’t mean that any hardship suffered by a woman can be ascribed to misogyny. The logical false move has been especially blatant in media coverage of Meriam Ibrahim, the Sudanese Christian sentenced to death for her faith and forced to give birth in chains.

Time and again, reporters and presenters have spoken of the scandal as an issue of gender equality, rather than anti-Christian discrimination – as though male converts to Christianity in many Islamic societies are not also at risk of the harshest penalties as well. The explanation for all this is not hard to find. While women’s rights rank high in the liberal hierarchy of victimhood, freedom of worship for Christians ranks low.

The blind spot has helped to obscure some awkward statistics, including that there is barely a country from Morocco to Pakistan in which Christians can worship entirely without harassment, and that “freedom of religion” in many Muslim-majority countries means the freedom to convert to Islam, not away from it.

The Qur’an does not set out specific punishments for so-called apostasy in this life. The notion that converts to other religions should be killed fed into all the main branches of sharia law via the Hadith, a later body of teaching. It is partly for this reason that Muslim attitudes should not be considered immutable – either by Islamists on the one hand, or hostile critics of Islam on the other. Many senior Muslims are far less circumspect, though. When the Grand Mufti of Egypt stated that Muslims were free to change their religion, he was rapidly contradicted by Dar al-Iftaa, Egypt’s most authoritative theological council.

Researching my book Christianophobia: A faith under attack three years ago, I interviewed twenty Afghan refugees in Delhi who had fled to India after being threatened with murder by their families for converting to Christianity. Nineteen members of this group were men. Herein lies a scandal that progressive Muslims – and secular liberals in the West – should be more exercised about.

June 2, 2014

May 30, 2014

“Art about what we know about war”

By Thea Lenarduzzi

Following Michael Caines’s “eve-of battle note”, I’m relieved to report that proceedings at “ANZACs at War: Writing about WWII and Vietnam” this morning remained peaceful. As Mark Dapin began telling us about his most recent novel, Spirit House, donning his “performing hat” (a New York Yankees cap, not a helmet, for the occasion), everyone looked very relaxed. We were surrounded by the ambrosial beauty of King’s College Chapel, after all.

Dapin started us off by describing his novel as a kind of “wish fulfillment”, written with his grandfather in mind. Which is not to say that the veteran at the centre of the novel, who toiled on the Burma Railway, is based on his grandfather (“I don’t think he ever left Leeds”) – but he was a cabinet maker, and at the heart of Dapin’s novel is the gently crafted relationship that grows between an elderly veteran and his thirteen-year-old grandson as they build a Spirit house, a shrine to hold the memories of atrocities he had known but never spoken.

Recovery after war, Dapin reminds us, is so often measured in terms of repression and silence, a severance of “during” from “after” based as much on the subject’s reluctance to revisit dark days as on the belief that nobody wants to know, or should have to. Even the most basic amateur psychologist could debunk this in a second. “We think of war”, Ashley Hay said, “as a tap that can be turned on and off.” But, of course, taps leak; one day you might get home and find your house flooded.

Hay came to write about war (in The Railwayman’s Wife) after a visit to Queen’s House, Greenwich, with its vast collection of war paintings. These examples of “art about what we know about war”, led her to interrogate the importance of “keeping war in the imagination”. A Spirit House of sorts, but one in which memories (first-, second-,third-hand), history and invention constantly change the layout. Fiction about war is necessary, she argued, citing a recent study which shows a link between the reading of fiction and the ability to feel empathy. (We might also relate this to the old prejudice against the novel as a feminine divertissement, not for real men…but perhaps that’s another blog.)

C. K. Stead was the only writer present who could say for certain that his novel had been used to make a point, as it were, about war: Smith’s Dream, “a political fantasy” about a Vietnam-type situation taking hold in New Zealand, was published in 1971 and adapted into a film, Sleeping Dogs, a few years later; now it is taught in NZ’s schools – “a boys’ adventure”, but one that allows teachers to branch into history, politics – and switch over to the film if attention starts to wane….

Film played a small part in the conception of Evie Wyld’s After the Fire, a Still Small Voice (2009). Not long after watching Total Recall (the Schwarzenegger one, very loosely based on Philip K. Dick’s story, from 1966, “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”), she diagnosed a similar blending of fact, fabrication and (selective) memory in her Australian uncle’s photo album from his time in Vietnam. Jungle, jungle, explosions, jungle, “a small dead boy in black pajamas”, a beautiful woman, jungle . . . . These documents – trophies or memorials? – spoke of a war that her family never acknowledged, but in which Uncle Tim fought. (Wyld’s mother, meanwhile, had moved to London and was taking to the streets to protest against it.) The scrapbook, kept but never openly shared, represented the contradictory impulses to share and to store away, to expose and to conceal, and led Wyld to ask him the questions nobody else had. (As Hay reminded us, the Australian Government’s failure to publish, until 2011, interviews conducted in 1946 with veterans suffering the effects of PTSD speaks of a similar discrepancy between the will to document and that to deny.)

Dapin closed – ambitiously, with only half-a-minute to go – with a far reaching point: because of the geography, Australia’s and New Zealand’s war writing had always been a kind of travel writing. For what is travel but a suspension of the day-to-day, and a chance to choose the things we take home and those we leave behind? Except it’s never as straightforward as that.

May 29, 2014

An ANZAC aside

An eve-of-battle note about the ANZACs, ahead of the event I'm chairing tomorrow morning at King's College London:

In my post about Australasian soldiers in later twentieth-century conflicts last week, I almost mentioned a minor incident in After the Fire, a Still Small Voice by Evie Wyld (one of the novelists who'll be speaking on the ANZACs at War panel). "Hold up your hand whoever's dad is out in Korea now", a teacher orders in class one day, in 1952. One boy, Leon, feeling sorry for the others whose fathers hadn't volunteered, holds up his hand "so high his shoulder clicked". The teacher shows them photographs of "the kinds of thing you got in Korea", to Leon's delight:

"You got muskrats and brown bears and tigers. His dad liked animals, he'd be excited to see a tiger. Leon imagined him lying on his front very still among the ferns and watching a tiger roll with its babies in the long grass."

It's a fearfully ominous naivety Wyld captures here, I think; the sort of enthusiastic innocence also found in, say, newsreel footage of happy soldiers marching off to certain victory with a dash of glory thrown in for good measure.

Something like Leon's view of the supposed joys of signing up and seeing the (natural) world is there, too, in the work of another of the speakers, Mark Dapin's Spirit House, in which the boy-narrator simply tells the reader: "I liked war, all the guns and tanks and uniforms . . . ." And sure enough, it's there again in C. K. Stead's Talking about O'Dwyer, in the war games two boys, among the bamboo trees – between them, they "shot a lot of Jerries".

I'm guessing, in other words, that we could find ourselves talking tomorrow morning just as much about innocence as experience – youthful expectations running up against bloody realities.

A further point about Leon's dad, though, and one that has acquired renewed and ugly unwelcome pertinence back here in the Old Country: he's a first-generation immigrant. Goaded into fighting – not exactly handed the white feather, not mobbed in the street – but clearly challenged by the immediate community around him to do something for his adopted country as it mobilizes for war, he and his wife argue in Dutch about his trying to prove he's "more Australian than anything else" (while she is described by somebody who presumably feels herself to be more of a native as a "Flaming clog wog"). How better to prove that, his actions imply, than to go off and fight for your country, and demonstrate your willingness to lay down your life for it?

So maybe we'll end up talking about immigration, too, then – albeit not in a sense that any gaffe-happy British politician, enjoying his moment in the sun after the recent local and European elections, would understand. "You know what I mean."

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers