Peter Stothard's Blog, page 40

August 26, 2014

Will Sept 18 dawn bright and sunny?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

What if the Scottish independence vote were suddenly thrown open to citizens of the rest of the UK, i.e. England, Wales and Northern Ireland? It would concentrate the minds of those of us who don't have the vote, wouldn’t it? It's conceivable, after all, that we haven't given the issue the mental space it demands.

I write as one who lives and works in the South-east of England and who is just back from Scotland (a last trip without a passport maybe). Superficial impressions from that trip would suggest a win for the “Yes” camp, in terms of the number of signs on display (the one shown above is on Mull), car stickers, flags, etc. In addition I saw a “Yes” convoy of cars on the outskirts of Edinburgh – there had been a rally apparently. Against that, I counted two “No thanks” signs. But then no thanks is not a great rallying cry, as has been frequently pointed out.

The staff at the “Yes” campaign headquarters in Dunfermline (above) we visited were confident of a win for their camp, which does appear to be gaining ground in the polls. And then there’s the matter of the second, slightly bad-tempered televised debate between Alex Salmond (“Salmond fishing for the yea men (and women)” as I think of it) and Alistair Darling last night, which the former is generally reckoned to have come off best from.

But what if, like me, you don’t truly understand the economic arguments, and are consequently easily swayed by both sides, as I find I am? Because, let’s face it, the debate has been mostly about economics and the pound, hasn’t it? What if, as a South of England-based Scottish friend of mine (who of course won’t be able to vote on the future of his country) suggested recently, the outcome could simply depend on how people feel on the day?

In which case, is it too fanciful to think that Alex Salmond will be praying that, rather than being a day of grey skies as above, September 18 will dawn bright and sunny?

August 15, 2014

Hugo Ball, Dada and “Elefantenkarawane”

By TOBY LICHTIG

In this week’s issue of the TLS (out today) David Collard reviews Hugo Ball’s Dada novel Flametti, which first appeared in German in 1916 but is only now available in an English translation (by Catherine Schelbert).

To accompany his piece on this “wildly inventive” little book, which – according to Ball – contained the author’s entire Dada philosophy (or, rather, anti-philosophy), Collard recently came into our studio to give a little background to the novel, to read out a passage from it, and to give a wonderful recital of Ball’s sound poem “Elefantenkarawane” (Elephant Caravan):

As Collard explains, this poem is meant to be performed. . .

And it was first performed by Ball – dressed in the extraordinary garb of a kind of “cubist bishop” (see above) – before a noisy crowd at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, 1916, and against the horrific backdrop of the First World War. It was a cross, it was said, between a liturgical chant and an angry “articulation of unreason”.

The liturgical element is important. Ball was raised a Catholic and died one, and – although Dada was anti-religion as well as anti-philosophy and anti-art – his poetry recalls, in effect if not sound, the Latin Mass, recited in a language unspoken by the congregation yet made familiar through repetition (the same could be said about the Ancient Hebrew chanted each day in synagogues across the world).

Ball explained that his sound poetry was based around “the equilibrium of vowels”, and, as Collard’s performance shows, the inflections that recall African as well as European languages reflect the Dada movement’s interest in primitivism and other non-Western forms.

You can subscribe to the TLS's occasional series of readings, by the way, via iTunes.

August 14, 2014

Lyon or Lyons?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In my post last week about George Sand I spelt the Balearic island under discussion “Majorca”, because that’s English style, but personally I prefer “Mallorca” – and indeed the Rough Guide spells it thus.

is, I confess, something of a personal obsession, even if I tend to go with the flow. I’m not one of those people who refer to Firenze and Napoli (except in reference to the football team from that city), but I make an exception for Mallorca: the “j” sounds potentially ugly to me, while the double “l”, Spanish style, is unambiguous.

Does anyone still talk of Leghorn when mentioning the Italian port of Livorno? Admittedly it probably doesn’t get much discussed now, except in a Byron/Shelley context. And while we’re on the subject of Continental towns and cities, is there any sense in persisting with the redundant “s” on Lyon and Marseille – unless, that is, one wants to pronounce that s? Otherwise, what useful purpose is it serving? (The TLS had a contributor who used to pronounce Lyon like the plural of a pride of big cats, but I think that was an affectation.)

When it comes to Greece’s second city, I am immovable: not Salonica, or those halfway houses Thessalonica or Salonika, but Thessaloníki – not forgetting that stress on the fourth syllable.

August 13, 2014

Buoyant Beckett

By TOBY LICHTIG

One final (I promise) aside about the recent Beckett Festival in Enniskillen. In researching Beckett's schooldays in Anthony Cronin's excellent biography, The Last Modernist (1996), I came across a poem the young Beckett wrote in the autograph album of his friend Tom Cox while the pair were students at Portora.

Beckett, seated on right. Photograph: Courtesy of Portora Royal School

I'd read Cronin's biography years ago at university but hadn't remembered the poem. Having pointed out the incongruity of staging a Beckett festival at all, I was struck by the peculiarity of this poem in relation to the author's later work, its jaunty optimism so wonderfully at odds with everything Beckett was to stand for.

Here is the (untitled) piece of verse in full:

When a bit of sunshine hits you

After a passing of a cloud,

And a bit of laughter gets you

And your spine is feeling proud,

Don't forget to up and fling it

At a soul that's feeling blue,

For the moment that you sling it

It's a boomerang to you.

As Cronin wryly comments of these lines: "So at variance with [Beckett's] own mature outlook and so appalling in certain literary respects are they, that one wonders whether they were not inscribed with satirical intent".

I've always found there to be something tremendously uplifting about Beckett's (often brilliantly funny) acceptance and exploration of uncertainty, fallibility, hopelessness, existential silence – just as the enforced buoyancy of this little piece of juvenilia can only feel humourless, crushing and constraining.

Perhaps, though, if Seán Doran's festival is to embrace its kitsch aesthetic to the full then this squib might become the event's ironic motto. Happy Days indeed.

August 12, 2014

Waiting for Godot . . . and waiting some more

By TOBY LICHTIG

One of the great pleasures of last week's Beckett festival was seeing Waiting for Godot twice in the same day. The prospect may strike some as gruelling but this couldn't be further from the truth.

A play so steeped in repetition and minor variation – not to mention boredom – naturally lends itself well to back-to-back performances, and these two productions contained enough by way of difference to make comparisons fascinating.

En Attendant Godot (with somewhat crowded English surtitles) is staged by the Théâtre Nono and directed by Marion Coutris. It courses with a subtle energy and a whiff of cabaret, from Estragon, with his face painted white, and the red-nosed buffon Vladimir, to Pozzo in his suspenders and boxer shorts. There is something wonderfully French about Vladimir's theatrically elongated way of calling out to his comrade: "Goggooooo".

A deep tenderness is established between the two eternal hobos, Vladimir stroking Estragon's feet as he helps him with his boots; and when they playfully mimic the slave and master ("On pourrait jouer à Pozzo et Lucky"), the sense is of a pair of children working through a trauma. The interplay between Pozzo and Lucky is similarly affecting, especially Lucky's physical performance as he sobs and gags, his dance at the end of Act I sliding into a comic grotesquerie that couldn't stop me from thinking of Ricky Gervais's infamous impersonation of MC Hammer in The Office.

Noël Vergès as Estragon and Christian Mazzuchini as Vladimir. Photograph: Cordula Treml

My only quibble with this excellent production is the unnecessary liberty taken with Beckett's very definite final stage direction: "They do not move" becomes "They move slowly off stage left". The stasis is respected at the end of Act I and it is hard to see what this interpretation adds.

The second version I saw was staged in Yiddish: suddenly the laconic, French Godot became a shrugging, Jewish one, the hobos remnants of a shattered Europe, communicating in a language rendered almost obsolete by genocide. In Vartn af Godot, staged by the New Yiddish Rep New York and directed by Moshe Yassur, the tree (which hangs surreally upside down in the Théâtre Nono's version) is a stark piece of metal piping; the sandbags around the stage are remnants of conflict; the ill-fitting shoes and trousers recall the deprivations of the concentration camps.

Yiddish, with its guttural vibrations, suits Godot very well, particularly at high moments of insult and exclamation. I particularly enjoyed the visceral “Alles drippit” (“Everything oozes”), “Zushmettert” (“appalled”), the boy’s shrugging “Ikh vis nit” (“I don't know”) and the notion that Godot may be coming for “Shabbos”. Pozzo’s “Happy days” is rendered as “L’chaim”. More jarringly, when Vladimir asks Estragon if he’s confusing the place they're thinking of with “the camp” (a line I can’t seem to find in my English edition of the play), the Yiddish “lager” carries with it a resonance that’s impossible to ignore.

David Mandelbauma as Estragon, Rafael Goldwaser as Lucky, Shane Barker as Vladimir, Allen Lewis Rickman as Pozzo

For all its interest, however, I found this version of the play less compelling than the French one. Riffing on the clichés of Yiddish paralinguistics, Shane Barker as Vladimir and David Mandelbaum as Estragon hammed it up a little too much, playing to the audience with facial ticks and gestures. Allen Lewis Rickman was a credible and overweeningly self-satisfied Pozzo, and it was instructive to compare Rafael Goldwaser's Lucky to Grégori Miege's one in En Attendant Godot. Goldwaser's presence was more minimalist than Miege's, his Lucky quietly broken, as opposed to grossly distorted. I found Miege's rather more persuasive.

One real treat of Vartn af Godot was the location: the old theatre at the Portora Royal School where Beckett was once a student (so too was Oscar Wilde, whose name was visible on the board of scholars). The thought of Beckett having once been in this hall, of his learning about theatre here, was not lost on the actors, whose joy was palpable in the speech they gave after the show.

Immersing myself in Godot, forgetting, at times, the language (I spent ten minutes ignoring the surtitles of the Yiddish version), was a thoroughly rewarding experience. By the time I headed home, reflecting on the four separate days on which Godot had failed to turn up, I was ready for a third version . . . perhaps this time in English.

August 8, 2014

Beckettland Enniskillen

By TOBY LICHTIG

Enniskillen is not the most obvious venue for the International Beckett Festival (which began on July 31 and runs until this Sunday). The small town in County Fermanagh, now in Northern Ireland, where the teenage Beckett boarded at the Portora Royal School between 1920 and 1923, does not, on the face of it, appear to have exerted much hold on him.

Though Beckett was popular at Portora, prospering at his studies and excelling at sports, few will be surprised to learn, in the light of his later work and general disposition, that his schooldays were not an era of untrammelled joy. . .

According to his biographer Anthony Cronin, the schoolboy Beckett was "moody, taciturn and, with most, uncommunicative". He never contributed to the school magazine. And as he grew famous, he refused all entreaties to return. "No invitation, no matter how pressing" would persuade him, according to the wife of a future headmaster.

Portora must have been a gloomy place when Beckett was there. Aside from the usual delights of British boarding schools of the era, including bone-shivering dormitories, there was the grim strife of political upheaval, as Ireland fissured into two, and the awful legacy of the First World War. At the festival, I heard a former Deputy Headmaster of Portora who is currently researching the fate of the school's wartime alumni provide a depressing welter of statistics and stories (“winner of the 100 metres in the summer; dead in France by Christmas”), and tales of teachers grieving for their former pupils. Beckett is often remembered for his relationship with the Second World War, but it was this environment that shaped his young mind.

Perhaps even more incongruous than the location, however, is the idea of a Beckett festival at all. There may not have been a rollercoaster called "The Void" but Beckett kitsch – two words that surely have no place in such proximity – was nonetheless everywhere apparent. Volunteers wandered around in "Team Beckett" T-shirts; at a café we really were served "Beckett-themed" chicken and turnip flan (sucking stone soufflé was mercifully off the menu). One location was decked out in the black and yellow stripes of Beckett's school colours; his craggy face plastered on billboards and lampposts, quotations displayed in windows: "I can't go on, I'll go on"; Wait a little longer, you'll never regret it". Wise to the irony of all this, the festival's founder and driving force, Seán Doran, has seen fit to name the grim-gay gala "Happy Days".

Yet who could begrudge Enniskillen its embrace of this wise, humane, supremely gifted son? Paris (the obvious choice) already bursts at the seams with literary heritage; Dublin too. Enniskillen is primarily remembered for the devastating IRA bomb that killed eleven people in November 1987. And the co-option seems genuine enough on a literary level. Events were extremely well attended, the audiences engaged. 8,000 people came along last year; more are expected this time around. Aside from the frivolity, Beckett was met with the seriousness he deserves.

Over a single weekend, I saw performances of Waiting for Godot (twice; of which more in another post), Catastrophe, the prose piece Texts for Nothing, the radio play Words and Music; Antony Gormley's Godot tree, a performance by the Gavin Byrars Ensemble of Beckett's poems set to music, various lectures and an exhibition. Plenty more was on offer.

For the performance of Catastrophe (directed by Adrian Dunbar), we were driven out to a ruined church in the countryside: a suitably menacing location for Beckett's short play (written for Vaclav Havel) in which an actor/victim, static on a plinth, is meticulously arranged by a pitiless director/dictator, before finally lifting his head in defiance. Something about the persecutor's mania for detail reminded me of Kafka's story "In the Penal Colony", an adaptation of which I reviewed for this blog last year. For the reading from Texts for Nothing, around sixty of us were taken out by boat to the eerie and isolated Devenish Island on Lough Erne, this time to a ruined monastery. Huddling around the actor Frank McCusker (who had also played the tyrannical director in Catastrophe), we listened on as the fragments of pure consciousness dissipated on the morning breeze.

Terry Eagleton was in typically wry and pugnacious form for his talk on "Political Beckett" ("Lack of knowledge tends to produce fewer corpses than ideological certainty") and, as if to highlight the importance of studied bewilderment, our trip was rounded off with a stage adaptation of the very challenging radio play Words and Music, in which the two art forms of the title compete with and complement each other. "All dark no begging / No giving no words / No sense no need" sings "Words"; the confidently discordant reply, by the Crash Ensemble orchestra, seemed to offer something more decisive. As Beckett himself put it: "Music always wins".

So too, in Beckett, does silence. He himself – meticulous about the way his works were represented – would doubtless have been appalled by Doran's festival. But he might also have found a begrudging glimmer of appreciation for the notion of giving it a go. As James Lord once commented of Beckett's friendship with Giacometti: "What they eventually found in each other's company was the supreme value of a hopeless undertaking".

August 7, 2014

George Sand (and Chopin) in Majorca

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

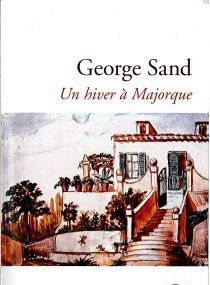

George Sand spent four months in the winter of 1838–9 in Majorca, together with her two children Maurice and Solange and her lover Frédéric Chopin, some six years her junior. The experience gave rise to Un Hiver à Majorque (1842, A Winter in Mallorca).

The book caused considerable offence to the islanders on account of its less than flattering depictions: “Travellers usually write about the good fortune of the southern races . . . . I have abandoned the idea since my visit to Mallorca. There is nothing as sad or as pathetic in the world as this peasant who knows nothing but praying, singing and working, and who never thinks . . . . If vanity did not wake him from his stupor from time to time and set him dancing, his feast days would be devoted to sleep” (in Shirley Kerby James’s translation – apparently that longtime Majorca resident Robert Graves also produced a translation of the text in the 1950s, although he noted “the bitterness” that the sojourn had “left in [Sand’s] heart”).

Later she writes, “When one wonders how a rich Mallorcan can spend his money in a country with no luxuries or any kind of temptation, it can be explained by looking into their houses at the grubby idlers of both sexes, who occupy a part of the house reserved for them . . .”. And again: “The men don’t read, the women don’t even sew. The only sign of domestic activity is the smell of garlic that betrays the act of cooking, and the only sign of private amusement are cigar butts squashed on the paving”.

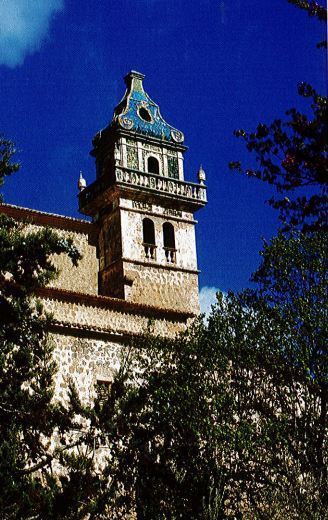

The group ended up staying in the Carthusian monastery of Valldemossa (“la poésie de cette chartreuse m’avait tourné la tête”), about 20 km north of the capital Palma, where they had disembarked (from Barcelona). Sand was impressed by the architecture of the villas in Palma and, of course, by its Gothic cathedral. She goes into some detail about the bureaucratic challenges presented by, and the costs involved in the need to transport Chopin’s Pleyel upright piano across rough terrain to Valldemossa (it is now on display in the monastery). While there, Chopin revised his 24 Preludes.

Valldemossa (above) made an impression: “When the sight of mud and fog in Paris makes me miserable, I close my eyes and see again, as if in a dream, that green mountain, those fawn coloured rocks, and that solitary palm tree lost in a pink sky.” So struck was she by the beauty of the scenery that she longed to bring her friend Eugène Delacroix to the island.

These were interesting times for the Balearics, with Carlist wars on the Spanish mainland producing a trickle of refugees to the islands. Sand notes all this, provides a short history lesson – the horrors of the Inquisition and persecution of Jews and Muslims/Moors in particular – and describes the reforms being undertaken by the Liberals, taking effect even on Majorca.

I put Chopin’s name in parentheses in the heading to this post as he barely features in Sand’s narrative, except as “notre malade”, “our invalid”: “All these fiery and heady wines disagreed with our invalid, and even with us . . .”. Her spirited children, indeed, are more prominent in the text. Chopin's absence is left unexplained, but maybe it was out of respect for a convalescent. In any case, it’s unlikely that Sand would have been struck by a bout of pudeur – that would not have been her style. Although, as Béatrice Didier, editor of the Livre de Poche edition of Un Hiver à Majorque (cover, above), points out, the cramped, shared sleeping arrangements in the monastery would hardly have been conducive to intimacy.

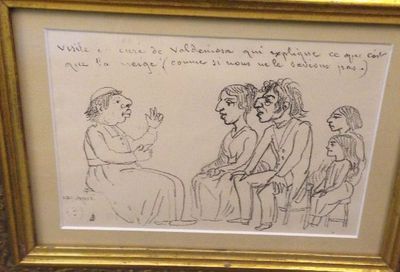

For all her complaints and criticisms, Sand appears to have developed a grudging respect for the locals as they struggled against harsh conditions. After all, she did write affectionately and knowledgeably about the peasantry of the Berry in her fiction, and was politically on the side of progress and reform. But her sharp tongue is never entirely absent here, as in her response to the local priest, captured in this drawing she made of his visit to her “family”:

The words read: “Visite du curé de Valdemosa qui explique ce que c’est que la neige (comme si nous le savions pas.)” – “priest’s visit during which he explains what snow is (as if we didn’t know.)"

August 2, 2014

July 30, 2014

Tales of Tove

Island living, Tove by Per Olov Jansson,1930; image courtesy of the Finnish Institute in London

By LUCY DALLAS

Until the end of August, the ICA is home to a small exhibition of photographs of Tove Jansson, best known as the creator of the Moomins (for children) but also the author of brilliant, spare short stories and novels (for adults). The distinction feels even more artificial than usual in this case; the Moomin books are far from cute and heart-warming, as the marketing would have you believe. There is plenty of solitude, angst and fear in these stories, and no shying away from unpleasant facts, whereas the "grown-up" writing is clear, simple and resonant.

To English readers familiar primarily with her books, it comes as a surprise to learn how popular the Moomin comic-strips were – featured in 120 papers across the world at their height. Jansson needed time away from the pressure and escaped, with her partner Tuulikki Pietila, to a remote Finnish island, Klovharu, where they were the only (human) inhabitants. Jansson called it an "angry island", and the conditions there could be hard – there are photos of Jansson sawing logs, mending fishing nets – and sometimes the weather would cut them off entirely. Yet there is fun along with the hard work; we see Jansson swimming with a wreath of flowers on her head, and walking barefoot, with a flash of red toenail – not quite as austere as one might think. There is also a beautiful shot of Jansson feeding her pet seagull; the bird is hovering, with a morsel in its beak, just taken from the outstretched bowl.

The island does feature in Jansson's fiction, and she and Pietila also published a book about it, Anteckningar från en ö (1993, Notes from an Island). The photos were taken by C-G Hagstrom, who became a friend, and Per Jansson, Tove's brother, over a period of sixty years, and they have a direct intimacy about them. The curator of the show and Director of the Finnish Institute in London, Susanna Pettersson, will give a talk on August 21 at 6.30, if you need more Moomins in midsummer.

July 25, 2014

Enduring War – with or without pepper

By THEA LENARDUZZI

On one of the hottest days of the year, I ducked into the coolness of the British Library for a little breather. Aside from the watercooler, I was attracted by one of the library’s current exhibitions, Enduring War: Grief, grit and humour, which runs along the back wall of the Folio Society Gallery, out of direct sunlight.

Insofar as grief, grit and humour could be separated in the midst of a war that obliterated most other things man thought he could distinguish, the exhibition brings together private and public ephemera – memorial rolls, photographs, official posters, a knitting-pattern for balaclavas – which has taken on new significance in this centenary year.

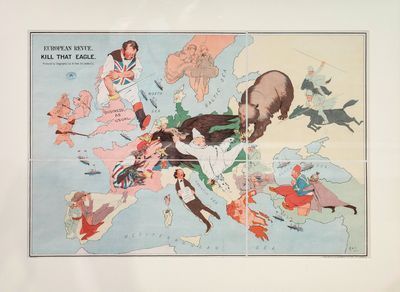

Walking into the section loosely held together by humour, I found examples of satire from both sides: the German Thomas Theodor Heine’s cartoon “The Englishman and his Globe” (1915), which shows a puny-looking colonizer desperately straddling his blood-soaked empire (“Curses! Blood is more slippery than water!”) confronts us with a very different embodiment of Britain than does the best-foot-forward, Churchillian muscleman of “Kill That Eagle”, produced in London in 1914 – the year before the then Lord of the Admiralty’s disastrous involvement in Gallipoli:

(The French, meanwhile, were depicting L’Armée du Kaiser as a bunch of wilting radishes, their Pickelhaubes bent and scraggly.)

Also on show is a parody of the Bayeaux Tapestry by Norman Rybot, a major in the Indian Army, who served in Egypt and Mesopotamia between December 1915 and April 1916. The cartoon compares the starvation he and his comrades experienced with the more bountiful circumstances (relatively speaking) of the upper echelons: “Certayne knyghtes fare ryghte svmptvovslie in ye beleagvered citie of Coote”, he finds, while “Certayne other knyghtes are lyke to dye of wante”. Here, food – and, specifically, a gnawed horse leg depicted in the cartoon’s lower pane – represents the fine line between humour and grief (no doubt with plenty of grit, too).

I found myself recalling countless scenes in Journey’s End when provisions – their inadequacy or utter absence – meant the difference between a good and bad war. Take this exchange, from Act I, between Lieutenant Osborne and the cook Private Mason, in the trenches of Saint-Quentin:

TROTTER (throwing his spoon with a clatter into the plate): Oh, I say, but damn it!

OSBORNE: We must have pepper. It's a disinfectant.

TROTTER: You must have pepper in soup!

STANHOPE (quietly): Why wasn't it packed, Mason ?

MASON: It, it was missed, sir.

STANHOPE: Why?

MASON (miserably): Well, sir, I left it to –

STANHOPE: Then I advise you never to leave it to anyone else again unless you want to rejoin your platoon out there. (He points into the moonlit trench.)

MASON: I'm, I'm very sorry, sir.

. . . .

OSBORNE: We must have pepper.

TROTTER: I mean, after all, war's bad enough with pepper (noisy sip), but war without pepper, it's, it's bloody awful!

In this company – military and domestic – pepper is a beacon of civilization amid barbarism, what the anthropologist Mary Douglas called a “stabilizing factor”.

Letters made a difference, too, of course. One soldier wrote to his brother: “You know letters from home are the only solace to me amidst the noisy cannonade, Rifle fire, Bomb reports from whizzing aeroplanes & and all other wild noises of unceasing butchery . . . .”. Not to mention good socks, as the artist Phyllis Garner (at home) explains in a letter in which she begs her lover, Rupert Brooke (then in Antwerp), to send his holey ones back to her for darning: “If we must be knitting, we, for the defenders of our country, why not for you in particular?”

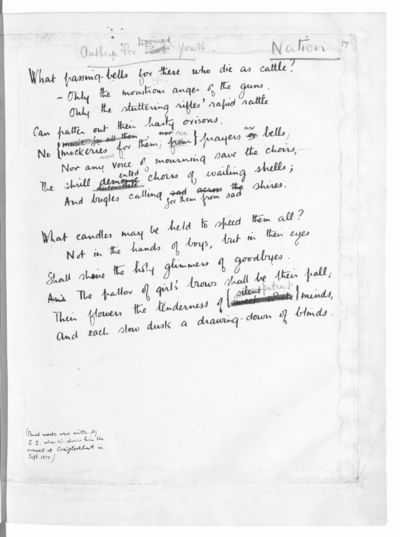

Brooke, in turn, found a kind of comfort amid the chaos – a purchase, of a sort – in his poems. “The Soldier”, scrawled by the poet in a letter to Edward Marsh in January 1915 (Brooke would die in April), is displayed here, as are originals of Laurence Binyon’s “For the Fallen” (1914) – an undated recording of which, made by the poet, plays over the sound system – and Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem For Doomed Youth” (1917), written while he was recovering from shell-shock.

Beside the young Owen’s words are those of a more mature companion, Siegfried Sassoon, who crossed out “silent” and replaced it with “patient” in the poet’s lines on “The pallor of girls' brows . . . . and the tenderness of [their] patient minds”; Sassoon gave the poem its title, too.

(By permission of the Estate of Wilfred Owen)

A copy of Sassoon's famous statement to the government, in 1917, against the continuation of war – for even the most patient of minds would have been broken by this war – is displayed in another part of the exhibition. In it, Sassoon expresses the hope that his protest “against deception . . . may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share and which they have not enough imagination to realise”.

Enduring War is, in this sense, a very gentle aide-imagination.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers