Enduring War – with or without pepper

By THEA LENARDUZZI

On one of the hottest days of the year, I ducked into the coolness of the British Library for a little breather. Aside from the watercooler, I was attracted by one of the library’s current exhibitions, Enduring War: Grief, grit and humour, which runs along the back wall of the Folio Society Gallery, out of direct sunlight.

Insofar as grief, grit and humour could be separated in the midst of a war that obliterated most other things man thought he could distinguish, the exhibition brings together private and public ephemera – memorial rolls, photographs, official posters, a knitting-pattern for balaclavas – which has taken on new significance in this centenary year.

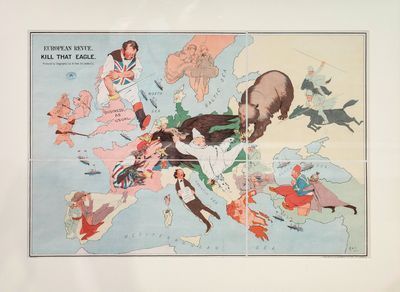

Walking into the section loosely held together by humour, I found examples of satire from both sides: the German Thomas Theodor Heine’s cartoon “The Englishman and his Globe” (1915), which shows a puny-looking colonizer desperately straddling his blood-soaked empire (“Curses! Blood is more slippery than water!”) confronts us with a very different embodiment of Britain than does the best-foot-forward, Churchillian muscleman of “Kill That Eagle”, produced in London in 1914 – the year before the then Lord of the Admiralty’s disastrous involvement in Gallipoli:

(The French, meanwhile, were depicting L’Armée du Kaiser as a bunch of wilting radishes, their Pickelhaubes bent and scraggly.)

Also on show is a parody of the Bayeaux Tapestry by Norman Rybot, a major in the Indian Army, who served in Egypt and Mesopotamia between December 1915 and April 1916. The cartoon compares the starvation he and his comrades experienced with the more bountiful circumstances (relatively speaking) of the upper echelons: “Certayne knyghtes fare ryghte svmptvovslie in ye beleagvered citie of Coote”, he finds, while “Certayne other knyghtes are lyke to dye of wante”. Here, food – and, specifically, a gnawed horse leg depicted in the cartoon’s lower pane – represents the fine line between humour and grief (no doubt with plenty of grit, too).

I found myself recalling countless scenes in Journey’s End when provisions – their inadequacy or utter absence – meant the difference between a good and bad war. Take this exchange, from Act I, between Lieutenant Osborne and the cook Private Mason, in the trenches of Saint-Quentin:

TROTTER (throwing his spoon with a clatter into the plate): Oh, I say, but damn it!

OSBORNE: We must have pepper. It's a disinfectant.

TROTTER: You must have pepper in soup!

STANHOPE (quietly): Why wasn't it packed, Mason ?

MASON: It, it was missed, sir.

STANHOPE: Why?

MASON (miserably): Well, sir, I left it to –

STANHOPE: Then I advise you never to leave it to anyone else again unless you want to rejoin your platoon out there. (He points into the moonlit trench.)

MASON: I'm, I'm very sorry, sir.

. . . .

OSBORNE: We must have pepper.

TROTTER: I mean, after all, war's bad enough with pepper (noisy sip), but war without pepper, it's, it's bloody awful!

In this company – military and domestic – pepper is a beacon of civilization amid barbarism, what the anthropologist Mary Douglas called a “stabilizing factor”.

Letters made a difference, too, of course. One soldier wrote to his brother: “You know letters from home are the only solace to me amidst the noisy cannonade, Rifle fire, Bomb reports from whizzing aeroplanes & and all other wild noises of unceasing butchery . . . .”. Not to mention good socks, as the artist Phyllis Garner (at home) explains in a letter in which she begs her lover, Rupert Brooke (then in Antwerp), to send his holey ones back to her for darning: “If we must be knitting, we, for the defenders of our country, why not for you in particular?”

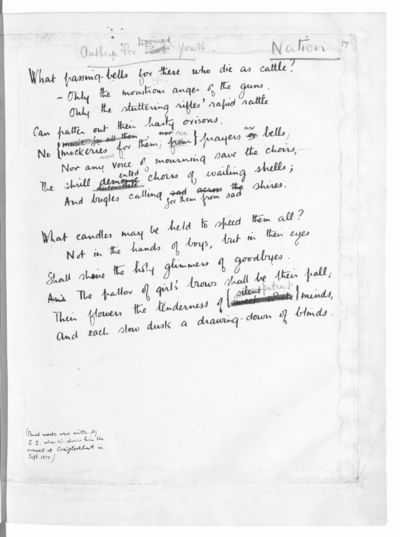

Brooke, in turn, found a kind of comfort amid the chaos – a purchase, of a sort – in his poems. “The Soldier”, scrawled by the poet in a letter to Edward Marsh in January 1915 (Brooke would die in April), is displayed here, as are originals of Laurence Binyon’s “For the Fallen” (1914) – an undated recording of which, made by the poet, plays over the sound system – and Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem For Doomed Youth” (1917), written while he was recovering from shell-shock.

Beside the young Owen’s words are those of a more mature companion, Siegfried Sassoon, who crossed out “silent” and replaced it with “patient” in the poet’s lines on “The pallor of girls' brows . . . . and the tenderness of [their] patient minds”; Sassoon gave the poem its title, too.

(By permission of the Estate of Wilfred Owen)

A copy of Sassoon's famous statement to the government, in 1917, against the continuation of war – for even the most patient of minds would have been broken by this war – is displayed in another part of the exhibition. In it, Sassoon expresses the hope that his protest “against deception . . . may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share and which they have not enough imagination to realise”.

Enduring War is, in this sense, a very gentle aide-imagination.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers