Peter Stothard's Blog, page 43

May 22, 2014

May 1814: Napoleon arrives on Elba

Napoleon arrives on Elba - the Art Archive/Alamy

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Next June will see the bicentenary of a certain battle on a plain near Brussels. But in the year before that climactic event, Napoleon was dispatched by his enemies to the Mediterranean island of Elba, 20 km off the Tuscan coast. According to the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau drawn up by his Prussian, Russian and Austrian opponents (Britain refused to sign on the grounds that he was a usurper and it didn’t want to grant him legitimacy), Napoleon signed a letter of abdication on April 6, 1814. Alan Forrest writes in his Napoleon (2011) that he received “in return the right to retain his imperial title, sovereignty over the tiny island of Elba, . . . and an income of two million francs a year, to be paid to him by the French government”.

Insisting on travelling on a British rather than a French vessel, on April 28 Napoleon boarded the HMS Undaunted at Fréjus on the French coast, and arrived off Elba’s main harbour Portoferraio, on May 3. The captive chose to stay on board until the next day, meeting political and religious representatives before disembarking – a “political” gesture in the words of Gloria Peria, a local historian quoted by Le Monde’s Italian correspondent Philippe Ridet who recently visited the island to witness the bicentennial celebrations. Napoleon remained there for ten months: the Hundred Days were therefore preceded by the 300 days on Elba.

Ridet points out that whereas Napoleon is regarded on the Italian mainland as a tyrant and pillager of art treasures, on the island he is remembered with “affection, compassion even”. As one would expect, he wasn’t idle. According to Antonella Giuzio, “one of the island’s cultural officials”, “he didn’t make war with anyone, he developed the economy of the island, and he left us an important legacy: his library and the houses he had restored to live in”. Ridet writes that no sooner landed, he designed a new flag, toured the island, visited the iron mines that drove its economy (hence, presumably, the name Portoferraio, a ferraio being a blacksmith), reformed the administration (something of a speciality), merged the civilian and the military hospital, signed commercial treaties with Livorno and Genoa. And, for good measure, he appointed three generals who had chosen to travel with him (as well as a thousand men), Bertrand, Drouot and Cambronne, as interior and war ministers and commander of the Imperial Guard, respectively. “Napoleon did what he was born to do” – even if in this case he was dealing with a population of 13,700 islanders.

But, Forrest writes, Napoleon soon became "both bored and frustrated with what life could offer on a small Mediterranean island . . . . As a ruler, albeit of a tiny state, he had set about providing for its defence, against both an Allied attack – never a likely occurrence – and the more likely incursions of pirates from the Barbary coast. To this end he raised an army of just under two thousand men, which included more than six hundred former members of his Imperial Guard who elected to follow him out from France”. And there was also a small navy, which would prove handy for escape. Sudhir Hazareesingh writes in The Legend of Napoleon (2004), that “From the moment Napoleon left France for Elba in 1814, many of his soldiers had begun to predict that he would return ‘when the next violets bloomed; hence his popular nickname of Père La Violette”.

Interestingly, Ridet reveals that the island was a “nest of spies”: “English, Russians, Austrians, French in the pay of Louis XVIII [the Bourbon king] walked up and down the quays after the slightest bit of information”. But how vigilant were they? Napoleon took advantage of the absence of Neil Campbell, the “unofficial British representative” on the island, to slip away on a frigate (adding a "handful of Corsican and Elban volunteers to his party", according to Forrest) on February 26, 1815. He landed near Antibes on March 1 with an army of 900 men and thus began the Hundred Days.

Meanwhile, actors have been re-enacting Napoleon’s arrival on the island (Franco Giannoni in the lead role above). Its tourist website quotes the words of the deputy at the time, Jean-Toussaint Arrighi: “L’isola d’Elba, già celebre per le produzioni della natura, diviene oggi più illustre nella storia dei popoli perché rende omaggio al suo novello Principe di fama immortale.” (The island of Elba, already celebrated for its natural resources, today becomes even more illustrious in the history of peoples because it is paying homage to its new Prince of immortal fame.)

In one little Mediterranean outpost the Corsican ogre's influence appears to have been entirely benevolent. And anyone visiting the island this summer might find themselves taken two centuries back in time.

May 21, 2014

To the book (and parasol) fair

This year's London International Antiquarian Book Fair opens tomorrow. It's an annual event over at the Olympia Exhibition Centre and, among other things, it gives those who have no intention or hope of parting with large sums of money for long-sought treasures the less costly pleasure of merely gawping at some of the most unusual and beautiful of books still on the market – as well as the sometimes unexpected objects that some astute dealer has picked up along the way. Hence the photo above: this is apparently one of Queen Victoria's parasols.

It's for sale together with a photo by A. J. Melhuish, in which the monarch is, most unusually, seen smiling (albeit "slightly") at her daughter Beatrice, standing beside her, parasol aloft. The lot could be yours, via Sophie Dupré, for £7,500. The same dealer is also has on offer a short but rather poignant letter from Charles Dodgson (£6,250) and the Countess of Clonmel's fan, signed by another pseudonymous writer, Samuel L. Clemens, among other luminaries (£3,250).

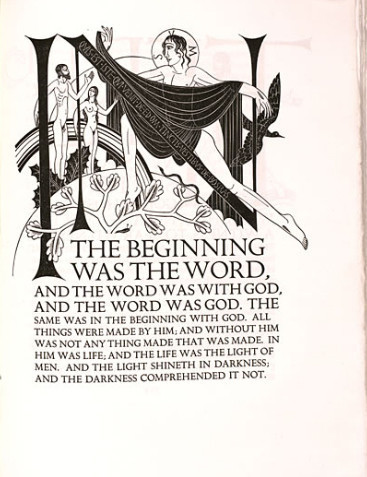

Not tempted? All right. If those prices seem somewhat beneath you: consider, as alternatives, the "extraordinarily clean and bright" copy of the Golden Cockerel Press The Four Gospels of the Lord Jesus Christ (Sophie Schneideman Rare Books, £11,500):

Or how about the "original concept album cover artwork" for the US issue of Jimi Hendrix's album Electric Ladyland (Lucius Books, £11,000)?

Or Shackleton's Heart of the Antarctic, in signed, limited and de luxe form, bound in vellum (Bernard Quaritch, £30,000), or the first edition of Pride and Prejudice in a contemporary binding (Jonkers Rare Books, £57,500), or The Wonderful Wizard of Oz signed by both L. Frank Baum and his illustrator, W. W. Denslow (Jonkers, £150,000). Or, to descend rapidly from six figures to three, perhaps Antiquariaat Dik Ramkema will pick up £335 for what seems to be a rarity, a Book of Trades (c. 1830), with plates; sure enough, "bookseller" is one of the listed trades, alongside plumber, house-painter and lighterman:

And so the gawping goes on. . .

May 20, 2014

ANZACs real and imagined

By MICHAEL CAINES

It’s not exactly the most stunning view New Zealand has to offer: a misty morning on North Head, overlooking Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour. Note the disused building, though – a remnant of the country’s coastal fortifications built in anticipation of attack, at various points in the past century, from Japan or the Soviet Union. A network of tunnels runs through this strategically significant promontory, connecting one heavy artillery position to another; apparently, the big guns were never fired in anger, and, as I learned a few years ago, when I took this photograph, the hill is now a national park.

New Zealand’s soldiers, by contrast, saw no shortage of action abroad – most famously alongside their Australian counterparts at Gallipoli during the First World War. The centenary of that prolonged battle falls next year, and will no doubt feature the same sort of reflection and revision of the historical revision that we’ve already seen in relation to the outbreak of the war in 1914. Less widely acknowledged outside Australasia, perhaps, is the part that these expeditionary forces, the ANZACs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) played in later conflicts: Australia’s most sustained military engagement, for example, was apparently in Vietnam, and it sparked the same kind of controversies there that it did elsewhere.

Writing about war’s power to beget literature in last week’s TLS diary column, J. C. noted that, besides the obvious poetry of the First and Second World Wars, Vietnam gave us memoirs by Tobias Wolff and Michael Herr, Korea Chaim Potok’s I Am the Clay and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (published in 1961, regarded by the author as a comment on the 1950s, but based on his own experiences as a bomber pilot dated from a decade earlier). Iraq, though? “If something of the calibre of The Quiet American has emerged from the conflict, we haven’t heard about it.”

I’ve heard of several Australians and Kiwi writers, on the other hand, who have written about both the front line and its delayed impact on life back home – distinctive work, I feel, for the dislocation between antipodean communities and Old World theatres of war. There is C. K. Stead’s Talking about O’Dwyer, for example, in which a Kiwi recalls how it all seemed to be happening “over there”, even though Auckland had black-outs, rationing and “signs saying DIG FOR VICTORY”. (Things briefly look more alarmingly close to home after Pearl Harbour and the Germans sink a ship, the bullion-laden RMS Niagara, “not far north of Auckland”.)

There is also Evie Wyld’s After the Fire, a Still Small Voice, a powerful dramatization of life after Korea and Vietnam for generations of men – and there’s a novel I started reading only yesterday, Spirit House by Mark Dapin, which begins with a brutal bulletin, from 1944, in territory that Ian Watt, the author of The Rise of the Novel, would have recognized from his time as a prisoner of war working on the Burma railway.

They’re not the only ones, of course, but, along with Ashley Hay (whose novel The Railwayman’s Wife features not only memories of war but, Russian doll-style, memories of writing about war), Evie Wyld, C. K. Stead and Mark Dapin are the writers with whom I’ll be discussing all of this (disarmed Auckland hillocks included, maybe, who knows?) at King’s College London on May 30, as part of the Australia and New Zealand Festival of Literature and Arts. TLS readers – and anybody who happens to read this blog, would you believe it – can purchase two tickets for the price of one for this event, ANZACs at War: Writing about WWII and Vietnam, merely by entering the code TLS241 at the virtual checkout. I can only assume it’s going to be a lively discussion, with plenty of knowledgeable opinions voiced – although whether that necessarily makes it an easier or a more difficult discussion to chair, I’m not entirely sure.

May 17, 2014

Does the TLS have (a) style?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I only ask what may seem a rather self-regarding question because I was recently made aware of the existence of an essay entitled “Sur le style du Times Literary Supplement” by Maxime Cohen. (Thank you to TLS reader and contributor George Walden for the tip-off.)

The essay appears in Promenades sous la lune (Grasset), a wide-ranging collection, as the titles suggest: “Petit éloge des ordinateurs” (in praise of computers), “Des vins”, “De la plus courte scène érotique de la littérature française”, “Au sujet d’Aristote”. Cohen, who is (or at least was when the book appeared in 2008) a librarian in Paris – well, more grandly, “conservateur général des bibliothèques” – is an essayist of the old school, prefacing his pieces with well-chosen epigraphs and eschewing an index. His “Propos sur l’e muet” (on the silent e) is particularly well turned and opens: “L’e muet ou muette est la plus grande beauté de la langue française”. And in this case the epigraph, from Voltaire writing to M. Deodati de Tovazzi on January 24, 1762, is so good that I quote it in full:

Vous nous reprochez nos e muets comme un son triste et sourd qui expire dans notre bouche; mais c’est précisément dans ces e muets que consiste la grande harmonie de notre prose et de nos vers. Empire, couronne, diadème, flamme, tendresse, victoire; toutes ces désinences heureuses laissent dans l’oreille un son qui subsiste encore après le mot prononcé, comme un clavecin qui résonne quand les doigts ne frappent plus les touches.

(roughly translated: “you reproach us our silent es as a sad and mute sound that expires in the mouth; but it’s precisely in these silent es that the great harmony of our prose and verse consists . . . ; all these happy word endings leave a sound that continues after the word has been uttered, like a harpsichord that resonates after the fingers have touched the keys")

The TLS essay turns out not to be particularly about the paper’s supposed style and more about the English essay tradition (but it’s good to know that a reader as discriminating as Cohen clearly sees the paper). He does point out how a TLS reviewer will “patiently pick out the errors of a historian who is in all other respects an established academic”. That rings true enough.

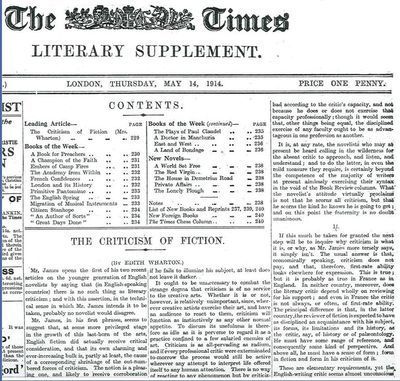

But is there such a thing as TLS style? A hundred years ago, as the excerpt at the top of the post shows, there was a certain formality: Mrs. Wharton’s repeated references to “Mr. James” would grate on the modern ear, and we are not told that the Mr. James in question is Henry James – obvious though it would have been to readers at the time.

I should say that I don't have an objection to the use of "Mr" or "Mrs" in a review – indeed it's sometimes appropriate and displays old-fashioned courtesy (rather than heavy sarcasm). But it can pall if it appears repeatedly.

When I started out on the paper, I was told that we referred to authors reviewed initially by their full name, and then by their title and surname and then just by the surname, before rounding off with the full name. The latter strikes me as unnecessary and liable to produce a jarring effect in a concluding paragraph – we don’t bother with it now – but we will, I hope, always overrule the occasional academic tendency to refer to authors just by their surnames from the outset.

The Times recently had a style overhaul, dispensing with what they saw as redundant capitalizations. Maybe we’re a little bit guilty of this at the TLS, i.e. “the West”, and should think again. It is the 21st century after all. Watch this space.

May 16, 2014

Reading dangerously

By TOBY LICHTIG

“I stand before you a sinner.”

Thus spoke Andy Miller, sombre, humble, bowed with contrition. He wasn’t the only one. There we sat before him, our heads hung low, contemplating our delinquencies, a congregation of literary penitents.

Each was handed a pencil and a small slip of paper. On this we wrote our names and the title of a book: a book we’d always meant to read but hadn’t quite got round to. A book we may even have lied about reading.

Our rehabilitation had thus begun. No more deceit and second-hand opinions, half-remembered shortcuts or self-deceptions. This was the first day of the rest of our literary lives: lives of healthy engagement and carefully acquired taste; lives of pride and action. Later, these slips would be read out in public. We would stand before our peers and admit to our lacunae, resolve to overcome them. First we had a therapy session to attend to.

Andy Miller's ten-step programme, designed to cure bad reading habits, is based on his new book The Year of Reading Dangerously (which I'll be reviewing in a future edition of the TLS). Beginning with “Choose books only for yourself” and ending with “Always tell the truth”, it is designed for those who love literature but have somehow lost their way, who believe they have read Middlemarch or Moby-Dick or The Master and Margarita by sheer dint of their enthusiasm for everything about them, only to discover that they merely own them, or thought they owned them, or once had a superb conversation about them in the pub without actually ever having opened them.

I must confess a bit of self-deception here myself. Each of these books featured in the talk but I include them simply because I myself have read them. It feels good to say so. I could instead have chosen The Communist Manifesto, The Odyssey or Wide Sargasso Sea, all of which I own, none of which I've read.

The literary dilettante Pierre Bayard has visited this territory before with his wittily disingenuous How To Talk about Books You Haven't Read, but Miller's aim is the opposite: to renounce this appalling habit for good. How To Read Books You've Merely Talked About might have been another title for his book.

Miller elected to write about the subject after he realized he'd been living a lie. Despite spending two decades immersed in literature, first as a bookseller, then as a publisher, he found he had little time for proper reading, or so he thought. Hurtling towards forty he realized there was a finite time left to enjoy the great literature he believed he would one day get round to. So he drew up a list, did nothing for two years, and then finally set to work. His method was to treat it like homework – fifty pages a day, no matter what. If he was struggling with a particular book, he struggled on. He gave up on nothing. “Always finish” is another of Miller's mantras (though I'm not sure I agree with him about this).

The event took place at the Radisson Blu Edwardian in Bloomsbury, as part of Hidden Prologues, a monthly programme of literary salon events. Around twenty-five of us were there to be chastened and entertained. Miller is an excellent speaker and he has honed his performance into a rewarding mixture of literary talk, motivational lecture and stand-up comedy routine (he's the editor of Stewart Lee, who's clearly a big influence). Along with summaries of his reading experiences, he treated us to some surreal anagrams (Herman Melville, Moby Dick becomes “Hmm, a credible milky novel”) and amusing flights of fancy, such as when he envisaged books rising up like robots against their pathetic human masters (“I see ebooks as a valuable first step”).

I'll save further comment on The Year of Reading Dangerously to the review itself, but in the spirit of Miller's project I wonder what readers of this blog would have written on that slip of paper had they been there. The evening's host, Sam Leith, chose Robert Musil's The Man Without Qualities: “James Wood is always going on about how wonderful it is but I know so little about it I don’t even know what qualities the man is without”. “Sam”, we all intoned, “You will read The Man Without Qualities.” Someone else chose Strikingly Different by Gary Lineker (“I've had it on my shelf for twenty years”). I chose Tristram Shandy, which I'm pretty sure I've written about but have certainly never read.

What, gentle reader, would be your choice? If you can bring yourself to write it down then you're part of the way there. To confess here is to commit to atonement . . . .

May 14, 2014

Beryl Bainbridge, novelist and painter

Dr Johnson in Albert Street with his Cat Hodge (2000, oil on board) © The Estate of Beryl Bainbridge

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Turning, he was confronted by an image of himself in the vast mirror on the gallery wall and did not recognise his features. It was as though the shaving glasses at Streatham Park and Johnson's Court, deceived by familiarity, had presented a false portrait, for here the mouth that he had privately considered generous appeared licentious in its fullness, and his large eyes, at home seemingly so expressive of candour, were lit with a sly regard, as of a man fixed on himself."

Which, as portrayed by Beryl Bainbridge in this paragraph from According to Queeney, Dr Johnson really is. The oil painting above, however, is also her work. It has Johnson, by contrast, sitting for his portrait at the table of her house in London, stroking his cat Hodge, and looking back at us.

He is a guest here as he is in the Thrales' house (as depicted in the novel); his head seems to me to be pretty much dead-centre on the canvas, but the scenery around him draws attention to itself, too, in the details of the cut-work, the flowers rising over him and the beaded lamp, as well as the aslant rectangles of the table and the window before and behind him. Perhaps something similar is going on in the passage I've just quoted from According to Queeney: Johnson's disturbed view of himself comes in the middle of another spectacle, a royal dinner; relief only comes when he escapes into the outside world where "white clouds flapped the heavens", "like sails in a blue sea".

This painting is one of two Johnson portraits Bainbridge produced as she was writing that novel about him and the Thrales fourteen years ago. Those who know According to Queeney and Bainbridge's other novels (Young Adolf, say, in which the protagonist describes himself "bitterly", following his rejection by the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, as a "painter of postcards") will perhaps find much "harmless pleasure" (Johnson'sseemingly grudging praise of his friend David Garrick's achievements as an actor) in the exhibition Art and Life: The paintings of Beryl Bainbridge.

Curated by Susie Christensen, it opens next week, on May 22, in the Inigo Rooms of Somerset House, and runs until October 19. Bainbridge had no formal training as an artist, but drew and painted all her life, apparently, and made a little money from that work, too, before she made any from her writing. She's by no means unique, I suppose, in being an adept in both visual and verbal media (step forward, Mervyn Peake, Ian Hamilton Finlay et al), but the close ties between the two are intriguing. Out of the associated talks, I'm particularly looking forward to hearing Brendan King talking about working with the novelist and his forthcoming biography of her, but also about a painting that depicts the same shooting incident from life that Bainbridge put into The Bottle Factory Outing. As above, such connections prompt the thought that maybe the concision and acute observations in the fiction are the result of her having, in some other sense, seen it all already.

May 13, 2014

Blinded by Bardolatry?

By MICHAEL CAINES

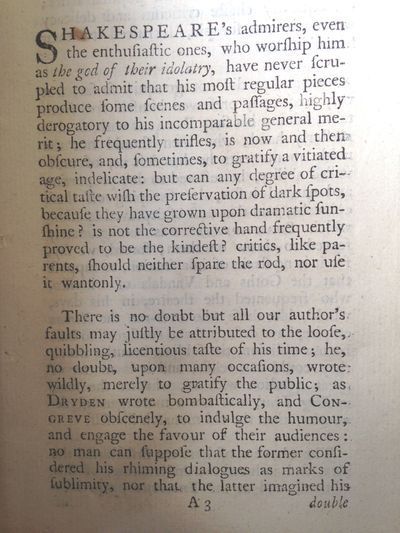

A postscript to yesterday's post about biographical imaginings, accidental or otherwise, on a connected point: here are the opening pages from a book by an eighteenth-century actor and critic, Francis Gentleman. The editor of what was once described as "unquestionably the worst edition that ever appeared of any English author" (an edition of Shakespeare published in the 1770s), Gentleman wrote extensively about Shakespeare and the actors of his day. He lived a rather hapless life, I think.

I couldn't say, in the Fertile Fact style, what Mr Gentleman would have made of Twitter or how he would have got on with Spotify, were he alive today; but I can point to these pages as a good example of how underlying biographical assumptions can shape (or deform) critical views. Specifically: how Shakespeare was so sublime a genius that he couldn't possibly be ultimately responsible for the more disagreeable elements in his work: "he frequently trifles, is now and then obscure, and, sometimes" – brace yourself – "indelicate".

Opening this particular book again (it's my fragile copy of a not especially rare edition, that will probably become one copy rarer if I open it again), I couldn't help but find something pertinent to what I'd just been writing about, in Gentleman's confident assertion that Shakespeare could do no wrong – and that the "loose, quibbling, licentious taste of his time" was responsible for anything smutty or less than sublime in Shakespeare's plays.

This is a conventional view for the period, when notions of the eighteenth century's inherent superiority to earlier times, such as Shakespeare's, held sway. To rewrite Shakespeare was fine (for example: giving King Lear a happy ending, as a Poet Laureate, Nahum Tate, had done, in the adaptation that still dominated the stage in Gentleman's day) because this was merely to reveal the "noble monument" beneath the "cobwebs". Adulation seldom equates with clarity of vision, you might say. Worshippers at literary shrines, take heed . . . .

May 12, 2014

Shakespeare, the Scots and the fertile art of biography

By MICHAEL CAINES

Arguments about the art of biography usually turn on questions about the past. Is biography properly a branch of historical writing, a matter of dutifully recording facts that happen to relate to a single life? Or is it more a matter of interpretation, of crafting those raw factual materials into something more like a novel? Is it ridiculous even to assume the distinction exists?

Given this tendency to think of biography as merely a matter of the past, I like the present-minded take on life-writing of The Fertile Fact, a website that both takes its name and adapts its guiding principle from Virginia Woolf's essay "The Art of Biography":

"Almost any biographer, if he respects facts, can give us much more than another fact to add to our collection. He can give us the creative fact; the fertile fact; the fact that suggests and engenders."

Run by Rhys Griffiths, the diverting "more" of The Fertile Fact is to invite "biographers/experts/super-fans" to see "famous authors and artists like fictional characters", but in relation to the present day. General, all too familiar themes emerge – anything to do with social media or scientific advances, for example – but they are "seen" from the perspective of somebody who lived without them and could only dream of life with them. There is also an idiosyncratic side of many of these portraits of the artist as a time traveller, as in Claire Harman's pen-sketch of Robert Louis Stevenson, that "notably scruffy dresser" and keen walker, in modern trainers.

Hence Strindberg's biographer Sue Prideaux likening the playwright's "celestographs" (a kind of photograph of deep space) to images from the Hubble telescope, and imagining how he would have taken to Twitter, on the evidence of his knack for an apopthegm. Also, Nicola Upson on how the crime writer she has made the protagonist in her own series of detective novels, Josephine Tey, would have taken to LoveFilm and watching the horse-racing on Channel 4; Michael Sherborne on the "futurity man" H. G. Wells and the banking crisis; and Baudelaire, as seen by Rosemary Lloyd, running up endless credit card bills and SMS-ing an urgent request for dosh. "Chère maman, please deposit more money into my account before close of trade . . ."

As these examples might suggest, playing this particular game requires a knowledgeable immersion in the world of the subject – a respect for and attention to facts, perhaps, that tend to be ignored when, for example, a biographical theory runs riot, as in the case of David Shields and Shane Salerno's compelling yet dubious Life of J. D. Salinger, and its view of the author as being, among other things, "unhealthily preoccupied with female innocence" and a war veteran whoes undiagnosed "post-traumatic stress disorder" shaped The Catcher in the Rye. It also goes missing when politicians and pundits turn to the past to find support for their views.

Reading the MEP Daniel Hannan's recent, not particularly convincing Spectator piece on Shakespeare "inventing" Britain, I noticed that Hannan wisely avoids saying "If Shakespeare were alive today, he'd be out there urging the Scots to vote in September to keep the Union" – "Patriots began appropriating Shakespeare almost as soon as he died", Hannan observes, with Ben Jonson's reference to "Britaine" triumphing over "all Scenes of Europe" thanks to the plays of Shakespeare gathered in the First Folio – but it's implicit throughout the piece that he'd like some of the supposedly union-endorsing wisdom of the great man ("the most complete human being ever to have lived" is the glass-shattering final note) to rub off on his more independent-minded readers.

It's no surprise that a few of Hannan's readers and commenters (yes, I know, only a fool reads below the line) cannot resist the temptation to ventriloquize the past in confirmation of their own views. "Shakespeare, today, would be arrested for 'Hate Crime', or killed by immigrants." (Gosh. Which bardicidal immigrants exactly?) "Can you imagine what the Victorians would be able to do if you brought them whole to this age with our technology?" (No, I can't. But that's a Queen's message I'd certainly like to see on Christmas Day.)

In the TLS diary column, J. C. has taken a more informed view of how James Boswell, Henry Cockburn, Jane Carlyle and RSL would cast their hypothetical votes: it's a tie, the facts suggest, until you take Mrs Carlyle's husband in to account. "3–2 against" would then be the result, "and that, we predict, is how it will come out in reality".

There's something like the Fertile Fact game going on, albeit not necessarily examined or understood, whenever we examine our own situation by the supposed light of some figure who isn't here to do the same – whenever somebody says asks what Jesus or Johnny Cash would do, imagines Beethoven rolling over (and telling Tchaikovsky the news) or, in some television drama, says "it's what Mum would have wanted!". So I look forward to hearing more of this sort of thing – more remonstration via Rabbie Burns, Robert the Bruce et al, well informed or not – as the great day of the referendum approaches. Well, I say "look forward" . . . which is it, forward or back?

May 8, 2014

Talking heads

I’ve always admired Alan Bennett’s biting humour, and hearing him talk with Nicholas Hytner (the Director of the National Theatre) in the Olivier Theatre last night confirmed him to be one of my favourite writers. “When a critic praises the outstanding performance of an actor and doesn’t think much of the play, it’s as if they assume a character’s written their own lines”, Bennett remarked. He spoke “from a playwright’s point of view”, and didn’t hold back – but isn’t honesty what’s so likeable about him and his work?

In the TLS of July 29, 1965, George Melly, reminiscing about youth theatre, singled out Bennett’s qualities just before he appeared with Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and Jonathan Miller in Beyond the Fringe:

“In 1960, in a restaurant in the Euston Road, four young men, eyeing each other mistrustfully, were talked into putting on a late-night review at that year’s Edinburgh Festival . . . . of the cast, however, only Alan Bennett was a convinced satirist. At the preliminary sessions before Edinburgh he had constantly pushed the phrase ‘tough and accurate’ as what to aim at . . . . He was also the only member of the cast with strong political feelings. If The Fringe was satirical, Bennett was really responsible”.

Compared to the others in Beyond the Fringe, Bennett said last night, he always felt costive at writing. But he then explained how in The Habit of Art (2009), a play about a fictional meeting between Benjamin Britten and W. H. Auden, he'd channelled the memory of this feeling into Britten's character.

The first play he attempted to write was set in a school in Leeds – sounds familiar. “It was terrible, but in a sense I was trying to write about school all my life.” Later in his career came The History Boys (2004): Hector and Irwin, apparently, were originally one character, and each classroom scene was the result of one of his three-minute bursts of writing. Talking Heads, written during the 1990s, was an easier, more liberating process. “They came to me almost intact, all at once, like poems”, though having said that, “I can’t do them now. I wish I could”.

We were treated – how could he have denied us? – to a mellifluous reading by Bennett from his memoir Writing Home (1994). Here he describes the appearance of Miss Shepherd, who lived in a van parked in his driveway and was the inspiration for his play The Lady in the Van:

“Hats were always a feature . . . . She also went in for green eyeshades. Her skirts had a telescopic appearance, as they had often been lengthened many times over by the simple expedient of sewing a strip of extra cloth around the hem, though with no attempt at matching . . . . When she fell foul of authority she put it down to her clothes. Once, late at night, the police rang me from Tunbridge Wells. They had picked her up on the station, thinking her dress was a nightie. She was indignant. ‘Does it look like a nightie? You see lots of people wearing dresses like this. I don’t think this style can have got to Tunbridge Wells yet.’”

Alongside unforgettable voices, he creates strong imagery. The idea for People (2012), Bennett said, sprang from a vision he had of a dishevelled woman in a fur coat and slippers (which is now the opening of the play). Like Miss Shepherd, George III in The Madness of George III (1991) and the serial killer in The Outside Dog (from Talking Heads, 1998), she is one of many “derelict, extreme characters”, Hytner suggested, “that Bennett insists to us are human, even though we wouldn’t want to spend time with them”.

And what does Bennett think of his own writing? Having been asked by a member of the audience which of his works he likes the most, his favourites were his first play, Forty Years On (1968), Sunset Across the Bay (1975), and “I have a sneaking regard for things that haven’t gone so well, such as Marks (1982)”. But then: “I tend not to go back" he added, "it’s indulgent. I just get on”.

Throwing both hands in the air in appreciation of the audience’s whoops and claps, you wouldn’t believe that he turns eighty tomorrow. On Saturday, BBC Four kicks off a season of celebration with a similar interview between the writer and Hytner, as well as re-broadcasting some of his television and film work. He shows no signs of slowing down (in fact, his memory for dates and actors’ names was sharper than Hytner’s). There’s talk of The Lady in the Van becoming a film, and both Bennett and Hytner hinted that another play at the National is on the cards in the next couple of years. It must be habit, I suppose.

May 7, 2014

From Eddie Cochran to Edward Elgar

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

A few weeks ago I blogged about the imminent handover from Jarvis Cocker to Iggy Pop on a Sunday afternoon show on BBC Radio 6 Music. I ended up by wondering what sort of music Iggy Pop would be playing.

Well, what I've heard so far has been pretty good and last Sunday he gave a masterclass in presentation. Under the rubric “In Praise of Beauty” (every show has a theme – last week’s, which I missed, was on “Sunny California”, and he nicely signed it off, I see, with “The End” by the Doors), “the musician known as Iggy Pop”, as he invariably introduces himself, kicked off with Frankie Avalon’s “Venus”. This was followed by Shocking Blue’s rather different “Venus”. But “some people like their Venus a little more perverse, so let’s put her in furs, with the Velvet Underground”. The same band featured again, with Nico and “I’ll Be Your Mirror” – “she [Nico] benefits from their presence”.

George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord”, the Sex Pistols’s “No Feelings” (beauty? Narcissism more like, as he acknowledged), Fellini’s composer Nino Rota’s “Pin Penin” from the film Casanova, Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay”, the Doors’ “LA Woman”, John Lee Hooker’s “Solid Sender”, Nina Simone, Roy Orbison . . . what was not to like?

Interesting that Pop should have confessed to “tearing up” when he used to hear Stevie Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour” as a kid. Who’d have thought it?

Oh, and there was a plangent cello piece by Edward Elgar (below), “Sospiri”, that I had never heard before in years of listening to Radio 3 – “Gee whizz, I like that” was the show presenter's verdict.

And the number that will have had people dancing around their kitchens up and down the land? Eddie Cochran’s “Somethin’ Else” (of which Sid Vicious once did a decent cover version). It was sad to be reminded that Cochran died in a car crash in 1960 (in England) when he was only twenty-one. What a talent he was. Aside from “Somethin’ Else”, he left us two universally loved songs, “C’mon Everybody” and “Summertime Blues”, which has, I think, the finest couplet in pop music:

“I’m gonna take two weeks, gonna have a fine vacation

I’m gonna take my problem to the United Nations . . ."

Next week’s themed show is entitled “Complaint Department”. I wonder whether it’ll include “Summertime Blues”?

To think that the BBC were on the brink a couple of years ago of axing Radio 6 Music as a cost-cutting measure. What a scandal that would have been!

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers