Peter Stothard's Blog, page 45

March 28, 2014

Toni Servillo’s ‘Inner Voices’ at the Barbican

By Thea Lenarduzzi

Eduardo de Filippo’s play Le voci di dentro (Inner Voices) was written over the course of a few days in 1948. A run at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano was followed by two television adaptations by De Filippo (the first in 1962; the second in 1978), which helped to make it one of his most well-known plays (he wrote over fifty). In recent years, however, it has received little critical attention – until, that is, Toni Servillo – flush with awards from La grande bellezza (The Great Beauty), his most recent collaboration with Paolo Sorrentino – turned his considerable talents as actor and director to reviving it and touring it around Europe. Last night – and for two more before moving on to Madrid and then back to Italy – Inner Voices ran, with English subtitles, at the Barbican.

Peppe Servillo as Carlo Saporito

This isn’t the first De Filippo play to be taken on by Servillo and his theatre group Teatri Uniti de Napoli: their prize-winning production of Sabato, domenica e lunedì (1959) toured Europe for four triumphant seasons from 2002. It too was subsequently adapted for television, by Sorrentino. De Filippo grouped Sabato, domenica e lunedì and Le voci di dentro together in his collection of comedies written between 1945 and 1973, La Cantata dei giorni dispari – "giorni dispari" (days of inequality) as distinct from "giorni pari", which De Filippo confined to a pre-war collection. For it was, of course, the Second World War and its aftermath that dictated the switch from “pari” to “dispari”.

Servillo’s sets are paired-down, modern or, rather, timeless: off-white floor boards, off-white walls, off-white chairs with faded raffia seats, and an off-white table centre stage. Many of the actors from Servillo’s earlier production reappear in Inner Voices, with the addition of Peppe Servillo, Toni’s brother in both real life and the play, where they are Carlo and Alberto Saporito. (A nod here to the family dynamic favoured by De Filippo, who cast his sister Titina in the play’s first run and his son Luca in the 1978 film.)

The play begins with the young Maria slouched over the table asleep. She is woken by Rosa and told to look sharp, have a coffee. Both plays in fact start with two women on opposite sides of middle age busying themselves organizing the family’s food in the kitchen. But while Sabato, domenica e lunedì’s Rosa distractedly prepares her famous a ragù for the evening meal, Aunt Rosa (Betti Pedrazzi), in Inner Voices, is concerned with making breakfast – including, for her nephew Luigi, the topsy-turvy dinner-breakfast mix-up of macaroni (burnt because this Rosa, too, is distracted).

One by one, the play’s characters are brought into the blur of the morning’s activity, with sleep still in their eyes. Maria recounts a dream – which begins with a church-going maggot emerging from the broccoli and culminates in her heart jumping out of her chest and running away from her – to Rosa and the caretaker Michele (Marcello Romolo) who pops in for a coffee. (People are forever popping in in De Filippo’s plays). Michele laments that he is no longer able to dream the vivid dreams of youth (“belli come operette di teatro”), while Don Pasquale Cimmaruta, the (seemingly cuckolded) man of the house, played by Gigio Morra, complains of insomnia.

Carlo and Alberto, ageing heirs to their deceased father’s furniture rental business – the religious festivals they used to rely on are either fewer, or sourcing cheaper chairs elsewhere – call in to see the Cimmaruta family. (Neither of them eat much, they tell Rosa – you just don’t when it’s only the two of you – and yet Carlo proceeds to eat the macaroni, as well as Don Pasquale’s plumbs, thus confirming the latter’s emasculation.) Alberto becomes convinced that the family have murdered his friend Aniello Amitrano (his name playing on the centre-piece of “agnello” – lamb – at every respectable pranzo pasquale . . . ) . The police are called to take the family in for questioning: “La famiglia rispettabile”, a favourite trope in De Filippo’s plays, is set up and blown apart. (Cimmaruta; cima rotta; broken top/spire/head . . . .)

And yet there is no body, no evidence. In fact, the more Alberto thinks about it, the more convinced he is that it was all a dream – brought on by the 10g of olives and the cold pig’s trotter he shared with Carlo the night before. But by now the dream has become a vehicle for suspicion and anger on a course of its own: it has, in a sense, become fact, with each family member accusing the other and begging Alberto to produce “il documento” required by the police to put the culprit away. On a veiled mezzanine in the background, the brothers’ uncle Nicola (Šparavierzi) – who, disillusioned with humanity, has taken a vow of silence, communicating rarely in a kind of Morse Code punctuated by fireworks – dies at the height of the farce. His last and only words are: “Per favore, un poco di pace!”

The minimal action of the play is carried by unpredictable dialogue of this sort (most of it in the Neapolitan dialect which De Filippo championed). Pauses, ellipses and inversions multiply. Uncle Nicola symbolizes the fate of man to be forever misunderstood by his peers. But if, in De Filippo’s version, the comedy tended more towards the absurd, Servillo restores the menace of the original text, bringing last night’s production closer to Pinter than to Pirandello. And while De Filippo’s characters suffered the peculiar neurosis and injustices of the post-war condition (including the anxiety of never knowing if there would be coffee, or a government, in the morning), Servillo’s show that the crises – economic, religious, moral, in both public and private spheres – are just as, if not more, endemic today.

March 27, 2014

Valérie Trierweiler and Paris Match

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The unofficial role of first lady in France is one commentators had difficulty in defining at the time of the messy separation between President Hollande and his partner Valérie Trierweiler (above) earlier this year. Perhaps if there is ever to be a “first man” in France, the role will be taken more seriously. After all, Ségolène Royal, Hollande’s former long-term partner and the mother of his four children, is still active in the Socialist Party and could stage a comeback – she ran unsuccessfully in 2007 and might yet have another go in 2017. Having said that, the leader of the far-right Front National, Marine Le Pen, looks a better bet for 2017 after the successes of her party in last Sunday’s first round of municipal elections (and the Socialists’ catastrophic showing in the poll): the city of Orange in the South is now in Front National control and things could get worse after this Sunday’s second round.

Trierweiler has her job as a “Grand Reporter” (the staff list also includes someone responsible for “rewriting”) with Paris Match to fall back on. Under the rubric “Regard de Valérie Trierweiler” she reviews books for the glossy publication (with a circulation of 600,000 plus). Two weeks ago she reviewed the autobiography of a handicapped swimmer (the most recent issue doesn’t have anything from her). It doesn’t on the face of it seem a very demanding role.

I sense that Paris Match’s reputation is bigger than its circulation figures would suggest. Roland Barthes devoted a chapter of Mythologies to it. Everyone, surely, has heard of the magazine. Founded in 1949, it blazed a trail in covering the antics of movie and pop stars – the cover image of Jean-Paul Belmondo, star of Breathless among other films (above) captures the spirit of the publication absolutely – and royalty. And I wonder how many times Catherine Deneuve (below) has appeared on the cover. The Grimaldi family of Monaco has provided abundant copy: the death in a car accident of Princess Grace, the marital problems and tragedies of her daughter Caroline, and the waywardness of her other daughter Stéphanie. And not forgetting the son Prince Albert, the reigning monarch.

But the magazine has a more international view, too. Its photo-journalism has always been of the highest standard, and it hasn’t shied away from covering political scandal: two weeks ago, the former president Nicolas Sarkozy appeared on the front cover in Carla Bruni’s loving embrace above the coverline “Spied on by the judges and betrayed by an adviser – Carla wants to fight on his behalf” (the most recent edition has a distraught-looking Mick Jagger on the cover and two articles on his late girlfriend L’Wren Scott).

In addition there are articles on the Malaysian airliner, the Parisian mayoral elections, which will be won by either the Socialist Anne Hidalgo or the Conservative Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (NKM) – the first woman mayor of the City of Light, in other words. Elsewhere we can read about the 76-year-old Frenchman Claude Dany whose artificial heart beat “7 million times” before he died, François Mitterrand’s tangled domestic arrangements, the current popularity of Pope Francis, or the plight of the Tatars of Crimea.

The Hollywood angle, meanwhile, is covered with a picture-led item on George Clooney and his Lebanese lawyer girlfriend Amal Alamuddin on holiday in Tanzania. And there’s a piece on Annie Leibovitz’s photography.

Sarkozy is clearly something of a house favourite as the most recent edition covers his trip to Nice where, in the company of Bernadette Chirac, he inaugurated an institute for research into Alzheimer’s disease.

And those looking for coverage of those ageless French rockers Johnny Halliday and Eddy Mitchell won’t be disappointed: there they are on p22, next to the announcement of a French tour in 2015. Rock on!

March 25, 2014

After Arden: Ann Thompson and Hamlet

By MICHAEL CAINES

A characteristically deft, Janus-faced observation on page 52 of John Carey's new book, The Unexpected Professor, has him going, as a boy, to see Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in Antony and Cleopatra, at the St James's Theatre in 1951. "Not that Olivier and Leigh were particularly bad", he recalls, "It was just that, as often with Shakespeare, when actors start to waddle around and gesticulate[,] it seems absurdly inferior to what your imagination has created from words on the page." The young critic comes fresh from reading all of three Shakespeare plays as set texts at school, and intoning Othello's suicide speech ("Soft you, a word or two before you go . . .") in front of the mirror at home, "wearing my red dressing gown, the nearest thing I had to Moorish garb", before stabbing himself with an imaginary dagger.

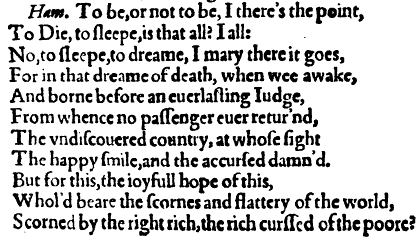

John Carey's recollections of coming away underwhelmed from seeing two great actors at work comes to mind after hearing the grandly named Annual London Shakespeare Lecture in Honour of Stanley Wells. This was given last night by Ann Thompson at the University of Notre Dame's London branch. Her subject was that most ubiquitous of Shakespeare's speeches – not necessarily a soliloquy, mind you – in which the Prince of Denmark weighs up whether or not he should –

Well, there doesn't exactly seem to be unanimous agreement about what "To be or not to be" is about. Suicide? Killing Claudius? Life in general? People keep changing their minds. Nor can they agree where the speech should go in the play Hamlet (theatre directors congratulate themselves on moving it so that it doesn't immediately follow, and contradict, "O what a rogue and peasant slave am I", but tend to pick a spot already taken by the so-called "bad" quarto, the first, of 1603), nor who hears it and from where (do Claudius and Polonius leave the stage altogether, or linger nearby?).

And then, as Professor Thompson (recently retired from King's College London, co-editor of Hamlet in the Arden edition, third series) pointed out, there are the verbal uncertainties and matters of interpretation in performance: is the poor man or the proud man's "contumely" that Hamlet counts among the "whips and scorns of time"? Is Polonius being considerate towards or dismissive of Ophelia when he turns to her and says "How now, Ophelia? / You need not tell us what Lord Hamlet said; / We heard it all"?

So Ann Thompson's rhetorical question was: when it comes to Hamlet, "have we heard it all?".

Her answer – or at least one of the many prudent observations in this lecture, which was well attended by her fellow editors, including Stanley Wells, the odd actor and, even odder, some members of the public – was that this supposedly all-too-well-known speech and the scene to which it belongs, 3.1, are full of perplexities to keep us guessing, to show us that we can't, and probably never will, have heard it all.

There's pleasure in these perplexities, too. After ten years' immersion in the task of editing it, and after seeing more productions of the play than she can count, Professor Thompson herself seems to have a preference for versions of Hamlet which can surprise her, rather than any convictions about the inherent superiority of her own view of the play to the absurdities foisted forth by waddling actors.

Peter Brook's staging in 2000 and 2001, she recalled, starring Adrian Lester, seemed to promise something very exciting: Hamlet without "To be or not to be". It wasn't in Act Two or Three. Would Lester leave it out altogether? But no, there it was, replacing its supposedly lesser counterpart, "How all occasions do inform against me", in Act Four.

I would have liked to ask her about women playing Hamlet (or directing it, which seems to be even more of a rarity) or maybe the temptation the actor Michael Pennington felt, comparable to her own desire for novelty, perhaps, to adopt the first quarto's version of that speech, "To be, or not to be, I there's the point . . ." (as above).

But open the door to this multiplicity of princes and their dilemmas, and you can see why the RSC once playfully suggested in their in-house magazine that there ought to be a moratorium on the play. And I can see why a friend of mine recently announced, only half joking, I suspect, that if we get round to holding our own Shakespeare evening, a (probably deeply embarrassing) private attempt at a 450th-anniversary celebration, he would be playing Hamlet – hands off! I was duly condemned to Mark Antony. Though whether he meant the Antony of Julius Caesar or Olivier-and-Leigh fame, or both, he didn't say . . . .

March 22, 2014

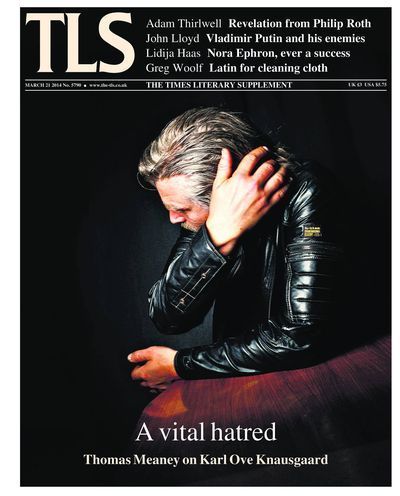

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

Karl Ove Knausgaard aims to capture “the tedious, repetitive and microscopic” aspects of life – and he has done so in a six-volume, 3,500 page novel in Norwegian called My Struggle. Pram-pushing, nappy-changing and the school run are some of the subjects on which he lingers. So too, the entry of bacteria into the heart, certain English rocks songs, and the impact of milk upon breakfast cereal. This week Thomas Meaney reviews the third part of the whole to appear in Don Bartlett’s “superb work” of English translation, making the preliminary judgement that its “extreme artlessness creates a far more intense realism than we might have thought possible, a confessional novel that outdoes most confessions”.

For the Emperor Vespasian the contents of a baby’s nappy would have been a potential new income source. As Greg Woolf describes, urine provided some of the essential chemicals for cleaning and brightening the woollen cloth that Romans used for togas and other uniforms of their day. The fuller’s trade was essential and profitable if little sung in history and literature. The phrase pecunia non olet (money has no smell) is attributed to Vespasian as a response to a fastidious complaint from his son and successor, Titus, about so unsavoury an addition to the tax take.

The smell of money is a matter of concern, sometimes akin to desperation, for those seeking to punish the rulers of Russia and Ukraine for the problems of Crimea. Confiscating the dirty assets of oligarchs would be one of the easier sanctions if one could sniff out what and where they were. John Lloyd, reviewing two books about supporters and opponents of Vladimir Putin, describes the depth of the new corruption and its links to the “centuries old norm” of survival that requires enriching those above one in the hierarchy as flagrantly as one enriches oneself.

Few of our literary critics have been as consistent sniffers out of the decadent rich as the Oxford professor and Sunday Times reviewer John Carey. D. J. Taylor praises the memoir of a writer and scholar who never found much to like in the Bright Young Things.

Peter Stothard

March 21, 2014

Wrath recorded

By MICHAEL CAINES

If you can skip past my inept introduction (only a couple of minutes, and then you get to the experts, as previously mentioned on this blog), here's the audio evidence of a discussion I chaired last month at the LSE. The subject of this debate, now a podcast, was The Grapes of Wrath, as well as questions of "wrath" – meaning the kind of righteous anger inspired by, say, extreme social inequality, racism, or sexism, and how it is expressed in literature today. There are novelists working now, somebody insisted, who share Steinbeck's sense of outrage – but could a novel have the same impact now that this book did in 1939?

Thanks to some differences of opinion on the panel itself and some excellent contributions from audience members, it turned out to be a lively and wide-ranging discussion. And it's one that will go on, in other forms and in other places, throughout this seventy-fifth anniversary year, particularly in the state (in Bakersfield and Salinas), where the Joads wind up, the family disintegrating under the sheer impoverishing pressure of the inhuman forces that drive them off their own small patch of Oklahoma.

Penguin, meanwhile, are reissuing the novel alongside several other Steinbecks. I like Jim Stoddardt's characteristically striking cover designs (here's TLS fiction co-editor Toby Lichtig, by the way, talking about book covers, also at the LSE: Don't Judge a Book by Its Cover); I'm not so sure about their decision, if that's what it was, to reprint the introduction by Robert DeMott without his name attached. But maybe that's a different debate.

March 19, 2014

A few stops with Richard Brain

By MICHAEL CAINES

Good proofreaders and sub-editors, we are told from time to time, are in short supply; but for many years the TLS was lucky to have what its former Editor, Ferdinand Mount, described as the Rolls-Royce service of two superbly tenacious correctors of grammar and spelling, pursuers of stray facts and upholders of consistency in house style. One of this team was the late Keith Walker – "a tall, elegant figure in a grey suit, with a packet of Gitanes perpetually to hand", as our diarist recalled. Those were the days, I remember, when you could still smoke in an office.

The other, Richard Brain (above), has just died at the age of eighty-five. One of John Gross's last appointments to the staff of the TLS, he worked on the paper, a retirement or two aside, for over a quarter of a century, after a notable career at Oxford University Press. There, as Literary Editor of OUP's General Division, he helped, among other things, to secure Athol Fugard's reputation on this side of the world and co-edited a new and greatly expanded edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

These achievements equipped him, like Keith, to write authoritative reviews on unfortunate attempts to occupy the same territory (he gave the Times Book of Quotations magnificently short shrift) and the occasional book or film. His first piece, for example, on the Uncollected Poems of John Betjeman, begins by suggesting that it's the kind of book that might be, as it were, "good for a few stops", "like a 104 bus when you're waiting at the Archway for a 43 or a 134 to take you to Muswell Hill", but ends with a warning about the "gushing, derivative foreword by Bevis Hillier which fills one with foreboding about the forthcoming multi-volume biography". And there's an enviable side-swipe towards the end of his piece on Dead Poets Society, that "romance of adolescent hopes and supposings", about the cast of "barely professional actors (Robin Williams not excluded)".

There were enthusiasms, too, though, to counter the barbs, as well as the anecdotes and benefits of his experiences in the publishing world – translating Georges Simenon, having dinner (mainly rice pudding, apparently) with Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, corresponding with Nancy Mitford. How many tyros and their typos he must have put right over the years.

March 18, 2014

The chronicler of Ferrara

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“I write about that time . . . only in the hope of understanding and of making others understand.” So ends the opening paragraph of Giorgio Bassani’s novel Dietro la porta (1964; Behind the Door). The narrator, in the depths of despair, speaks of a “secret wound bleeding” – a brief childhood betrayal that’s seared in to his memory and has made the ensuing decades of his life “useless”.

“It’s a powerful reminder”, said the novelist Paul Bailey last night at a Royal Society of Literature talk to celebrate Bassani, “how certain moments, even if trivial, can haunt you.” And this is what the Italian writer does best. Narratives in Bassani’s work are often barely there; it’s the relationships between the characters and his imagery that take centre stage. In the TLS of April 16, 1964, Margaret Bottrall wrote of Bassani's “elegiac feeling for those who suffer . . . [his] prose has always been meditative and lyrical, and his characteristic atmosphere that of twilight”.

We heard snippets of Bassani’s writing in the original Italian followed by their English translations from the poet Jamie McKendrick (who is currently translating Bassani’s collected works, Il romanzo di Ferrara, for Penguin Modern Classics). McKendrick began the discussion, which was chaired by Peter Parker, with one of Bassani’s early poems, “Verso Ferrara” (“Towards Ferrara”). Striking images (“lingering red on city towers”, “bare wood benches”, “fingers of laced lovers”) were the result, Bassani wrote in a postscript, of a train journey to Ferrara (where he grew up) viewed from a third-class compartment. An image of students going back and forth on the same train opens Bassani's book Gli occhiali d'oro (1958; The Gold-rimmed Spectacles). “Here autobiography and fiction overlap”, said Bailey. “Bassani’s books precede what we now call ‘faction’.”

In an interview, Bassani confessed to being a laborious writer obsessed with accuracy. He would write and rewrite every page “with the intention to tell the truth, the whole truth”. But his precise typography of streets, the locations of brothels, the names of cafés and obscure Italian political parties (which now require footnotes) goes beyond historical documentation because he adds his own experience – of Ferrara, and, in particular, of the city’s Jewish community and what happened to it after Mussolini’s Racial Laws were introduced in 1938. As a young Jew during this period, he encountered the social ostracization, fear and confusion that he describes so effectively in his books.

There’s a similarity in Gli occhiali d'oro between the exclusion of the Jews and of the homosexual Dr Fadigati, the novel's protagonist and victim. The crucial difference in this book – McKendrick argued – is that the Jews were initially accepted by society and suddenly found themselves pushed out. But it’s when the community discover Dr Fadigati’s “secret” (his homosexuality) that they decide to isolate him. In one dynamic scene, McKendrick recalled, a mongrel dog follows Dr Fadigati around the streets of the city. They pass a brothel, overhearing a seedy conversation, and witness a Fascist group of kids urinate against a wall, before a mist descends and obscures the view. “There’s a sense that Ferrara is a hellish city of predation”, McKendrick said. The parallel of the treatment of homosexuals and Jews emerges through the author’s intricate subtleties.

“He doesn’t tell you about history. He shows it to you through individual, ordinary lives with a lightness of touch”, continued Bailey. McKendrick, however, pointed out that the description of the synagogue in Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (1962; The Garden of the Finzi-Continis – Bassani’s most famous novel, which was adapted into a film in 1970 directed by Vittorio de Sica and starring Dominique Sander and Helmut Berger) is a tremendous piece of architectural writing, “like a guide book”. Members of the audience quickly debated whether the Finzi-Contini’s extensive garden exists in real-life Ferrara. One woman claimed it did and that she’d found the wall on which the narrator rests his bicycle; whereas some preferred to think of it as an imaginative amalgamation of gardens.

Parker finished by describing Bassani’s writing style as cinematic. Long sentences (lots of parenthesis, asides and qualifications), pauses and a “detached sympathy”, he argued, show a peculiar respect for the privacy of his characters, as if they’re autonomous. Proustian in flavour but instead of “worrying away at his characters like a terrier, [he] dangles them in the air, doesn’t tie up the ends, leaves spaces”. Perhaps it was his fondness for long cycle rides, to urge on and put off writing, that shaped his work.

March 17, 2014

Muddied oafs and Irish triumph

Brian O'Driscoll celebrates. NPHO/Dan Sheridan

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This post is mostly about rugby, so please, non-rugby fans, feel free to stop reading now.

Ireland won the 2014 Six Nations championship on Saturday, just in time for St Patrick’s Day today, by narrowly defeating France (22–20) at the Stade de France in Paris. (England had comfortably beaten Italy in Rome earlier in the day, and therefore finished with the same number of wins as Ireland but with an inferior points difference.)

I hadn’t watched any of the Six Nations matches this year, but sensed that the France–Ireland game would be one not to miss. I was right: it was a pulsating match, with both teams giving it their absolute all. Spice was added by the fact that it was to be 35-year-old Brian O’Driscoll’s last match in Irish colours. The buccaneering centre went out with a Man of the Match award and all sorts of records to his name: most number of Test caps (141), most tries in the Six Nations (26) etc. The game will miss him and Ireland will certainly miss him: he’s a once-in-a-generation player.

O'Driscoll scored a hat-trick of tries the last time Ireland won in Paris in 2000, carving up the French defence with pace and swerve.

Stu Forster/Getty Images

And how the game has changed. In spite of the photo above, it’s now less a case of muddied oafs (to borrow the title of Richard Beard’s 2003 book) lumbering up the pitch, while the “Jessies at the back”, as a former England forward once labelled them, nimbly evade tackles. International pitches are invariably pristine rather than mudbaths. Forwards and backs have become almost physically indistinguishable, all rippling muscle and thick necks, many weighing well over 90 kgs.

You could say that the professionalization of the game in the 1990s drew some of the romance out of it (think of Wales’s rampaging team of the mid-70s, all imagination and guile). Teams now have the vast array of technicians we see in other, more professionally established sports: specialist coaches, dieticians, psychologists; laptops are amply in evidence, in an attempt to reduce the error count in players’ performances. It doesn’t always work though: late in the France–Ireland match on Saturday the hosts had a great opportunity to score a winning try but fluffed it with an (illegitimate) forward pass. No amount of psychologizing, it seems, can counter the pressure of the moment. Which is reassuring surely.

In a TLS review of Richard Beard’s book the late Mick Imlah struggled to find many literary connections with the elliptical ball game: he came up with Kipling, Wodehouse, Conan Doyle, John Buchan. One might add Imlah himself, with his elegy for his friend Stephen Boyd: "So we put you at full-back, farthest away / From the kick-off, at least; you had arrived / In a pair of khaki shorts (we played in black), / Which in a private reference to the kilt / You wore with nothing underneath, and kept / Your heavy-duty glasses on as well". In his review Imlah derided the hideous moniker “Team England” as well as English players’ tendency to refer to “the guys”. This last habit has, alas, spread, as the charming French coach Philippe Saint-André spoke after last Saturday’s match of how “Ze guyz was being criticized” in the French press.

It’s unquestionably true that English rugby teams (“the guys”) have often had an image problem: dourness and lack of flair (a term traditionally ascribed by commentators to French teams, as in “Gallic flair”) complemented by occasional arrogance; then there are the rah-rah supporters with their unofficial “Swing Low” anthem and chunky sweaters.

The Six Nations tournament, made up of, along with France and the newest competitor Italy, four teams from the British Isles – England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales – has often had a certain edge: how Scotland love to beat England (it doesn’t happen very often). As do Wales of course. In February 2007, when their usual home stadium Lansdowne Road was being redeveloped, the Irish team hosted England at Croke Park, apparently the third largest stadium in Europe. It was also the scene in November 1920 of a massacre by the Royal Irish Constabulary during a Gaelic football match.The match in 2007 passed off without incident, even with the playing of the anthem “God Save the Queen” (I guess that's the "English" national anthem – how complicated it all is). Ireland won by a record margin of 43–13. Their captain that day was Brian O’Driscoll.

March 14, 2014

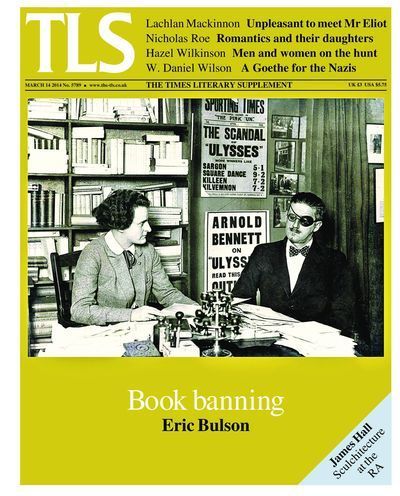

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

John Horne Burns was once “extravagantly acclaimed” and is now “virtually forgotten” writes Eric Ormsby this week, reviewing David Margolick’s “excellent and highly readable biography” of a writer who illuminated the sexual life of Americans in Naples in the aftermath of the Second World War. Burns’s once bestselling novel was called The Gallery, after the nineteenth-century city centre arcade where Italian men and women offered sex to GIs in exchange for cigarettes and gum. Burns was fearless, for his time, in writing “what is often cited as the first open description of homosexual life in American literature”. To be gay was to be “dreadful” – both as noun and adjective, a code word that worked its way into popular comedy of the 1950s. Dos Passos and Hemingway were impressed by The Gallery, but Burns died of sunstroke in 1953, despondent, suggests Ormsby, at the later trajectory of his career.

During the war, Burns was both a brutally frank observer and a censor of letters from prisoners of war. Eric Bulson considers the paradoxes of an earlier generation of censors struggling to deal with the national interest and with vigorous descriptions of sex. The neologisms of James Joyce caused difficulties for authorities around the world. Americans saw the publication of Ulysses in the 1930s as a brave response to book-burnings by Hitler even though Ulysses was not, in fact, banned in Germany till 1938.

Burns was a failed novelist before he reached Italy, and his biographer argues that it was the war which removed his “ungenügender Selbstsucht”, a term for the insatiable love of self which he found in “Harzreise im Winter” by Goethe. W. Daniel Wilson describes how the “exaggerated Goethe cult” in Germany today sits uneasily with the stories, still hidden in Weimar archives, of how the Nazis used the writer, who is “still a central touchstone for national identity”. Wilson recommends that the street in Goethe’s home town named after his Archive’s “committed and active anti-Semite” director, Hans Wahl, should be renamed for Julius Wahle, his Jewish predecessor.

Peter Stothard

This week's TLS is available to read now, both in print and as an app for the iPad, Kindle and Android devices.

Whish! James Joyce's river speaks

by THEA LENARDUZZI

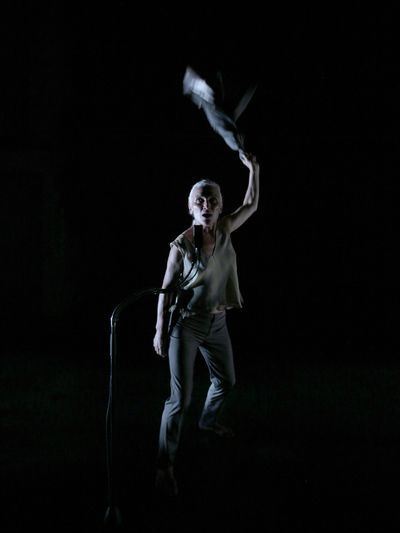

“The order is othered.” This is one of the few lines I can quote with any certainty from riverrun, Olwen Fouéré's one-woman adaptation of Finnegans Wake, performed in England for the first time this week at the Shed. But, then, it might have been “The other is ordered”, for no sooner had Fouéré said the words than they were carried off on an unpredictable tide of language which ran, without interruption, for just over an hour. Another line bobs to the surface, now: “I'll be your aural highness”; or was it “your oral heinous”?

Fouéré is a striking figure, in a grey silk camisole, her silver hair tied back loosely, as she snakes her hips gently, shifting her weight from side to side. She took as her starting point, when devising her monologue, the famously interrupted last line in Book Four (the beginning of the end of Joyce's masterpiece): “A way a lone a last a loved a long the” – which comes full circle to the book's very first line, “riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs”. Book Four sees Anna Livia Plurabelle – the embodiment of the river Liffey, or Life, which runs through Dublin and, indeed, through everywhere and everything – be swept out into the sea of time. Fouéré speaks for the river. Her first three words are Sanskrit, “Sandhyas! Sandhyas! Sandhyas!”, meaning the break of dawn, and there are echoes, too, as Fouéré stands before us, of Molly Bloom's “and yes I said yes I will Yes”.

But to make this comparison is, perhaps, to ignore Joyce's comment to friend while writing the book he preferred to call his Work in Progress (a process which took him roughly seventeen years, or “at least 1,200 hours”, Ian Pindar says in his biography of Joyce): “Je suis au bout de l'anglais” – and this from the man who had once declared English “the most wonderful language in the world”. The upshot, Finnegans Wake, is a triumph of multilingualism, or, in a sense, supralingualism – a “language which is above all languages”, “pure music” (in Joyce's words). This is, perhaps, never more alive than in Fouéré's soundscape which, as the novel itself puts it, makes “soundsense and sensesound kin again” – doubly heartening considering that most people will never read Joyce's original, “the greatest experimental novel of all time” (Pindar again) or “the best example of modernism disappearing up its own fundament” (as J. G. Ballard saw it).

As a result of the process of cannibalization to which Fouéré has subjected Joyce's text – “moving backwards towards the source ... intuitively selecting journey points, skipping chunks of text, inserting a couple of short passages from earlier in the book” – motifs recur and themes emerge. The story of Joyce's life, for instance, is brought closer to the surface. “As is, without a doubt”, Fouéré explains, “the voice of Lucia, Joyce's incarcerated daughter, with her silenced rage, her dancer's brilliance and the multilingual fire of her wit.” Daughter and father wash together in the riverrun, and joy and mourning become indistinguishable in Liffey's exclamation as it nears the sea: “I rush, my only, into your arms. I see them rising! Save me from those terrible prongs! Two more. Onetwo moremens more. So. Avelaval . . . Whish! A gull!” She is born – “a gull!”, a girl – into an ocean of opportunity, and at the same time she is undone, pulled under and lost in the depths.

Fouéré perfectly captures the babbling nature of Joyce's prose, the chopping and changing between register, theme, tone – conversational, almost cute, one minute, garbling the Ten Commandments and spitting damnations the next. She has described the Wake as “a seam of dark matter somewhere between energy and form”, an interpretation close to Samuel Beckett's that “Here form is content, content is form . . . . [Joyce's] writing is not about something; it is that something itself”. And, as all hope of narrative structure or fixed characters goes asunder to sound, it is this something that asserts itself; for, by bringing the rules of logic crashing together, swishing them around, drowning them, splicing them and turning them on their heads, a new order emerges, fluid and unfixed, which performer and audience understand implicitly. We all laughed at the same moments (for, lest we forget, Joyce proclaimed himself “a great joker at the universe”) and leaned further forward in our seats, as though to catch some secret wisdom, at others.

The performance culminated in a well-deserved standing ovation for Fouéré; and, of course, for Joyce's book itself, still something of a work in progress, after all, still fulfilling the author's intention “to keep the critics busy for three hundred years”.

Olwen Fouéré's riverrun is at the Shed until March 22.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers