Peter Stothard's Blog, page 48

January 31, 2014

At home in Malta

By CATHARINE MORRIS

One of the many things I didn’t know about Malta until a fortnight ago, when I joined the audiences of its second International Baroque Festival, is that to English ears a Maltese accent can sound strikingly Welsh. Among the first local people I heard speak at length was Kenneth Zammit Tabona, the Festival’s director (who is also one of Malta’s most popular painters, one with a vaguely Beryl Cook-esque charm), and I imagined that he had spent time in the Valleys, perhaps . . . . But later I noticed a similar lilt in the voice of our tour guide Mariella.

I wonder what accounts for the similarity – coincidence, I suppose; I’m guessing not British rule (from the 1800s until 1964), though that period is very much in evidence – in red telephone boxes, three-pin plugs, driving on the left-hand side, names and, above all, the use of English, which remains an official language. Signs are in English, and almost everyone speaks it. (And in Malta’s capital city Valletta, you’ll see Marks and Spencer, Peacocks and Accessorize – no wonder the British expat community feels at home . . . .)

It’s almost difficult to reconcile such – for some of us – homely touches with Malta’s more distant past: Malta may be small (a fellow Londoner compared it fondly with the Isle of Wight; and I happened to meet a retired teacher who had taught both the Prime Minister of Malta and the Leader of the Opposition), but it is certainly rich in cultural history: its rulers have been Phoenician, Roman, Byzantine and Arab, and on the island of Gozo (twenty-five minutes from Malta by ferry), you can visit what is thought to be one of the oldest free-standing structures in the world – a clover-shaped temple built around 3,400 BC. You can walk inside it – almost unaccompanied, if you go in winter – and contemplate its sacrificial altars. By the entrance you’ll see the spherical stones on which the limestone walls were transported, looking as if they were left there last month, or the month before.

A defining moment for Malta came with the Great Siege of 1565, and the Knights of the Order of St John of Jerusalem (described with some colour in this TLS review of Malta of the Knights in 1929) have been central to its development ever since. Having chosen Valletta – named after the Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette – as their stronghold, they set about building their city in a sumptuous baroque style. St John’s Co-Cathedral (home to two Caravaggios, one of them the huge altarpiece the "Beheading of St John the Baptist") was built between 1573 and 1577 and later decorated by Mattia Preti. Preti was to Valletta, Zammit Tabona told us, what Bernini was to Rome.

“We were in the EU before the EU was invented”, Zammit Tabona went on to say: the Knights came from all over Europe, and each of the cathedral's chapels is dedicated to a different nation. He called St John’s “a repository of our history – it is our Vatican, our Westminster Abbey. We love it passionately . . . . The big concert had to be there”. The big concert was Bach’s B Minor Mass performed by the English Concert and conducted by Harry Bicket. I was among the 1,000 people who gathered for it, and the sense of occasion was as enjoyable as the music.

St John’s is one of a number of churches used as concert venues, but at the festival’s heart is the elegant and intimate Teatru Manoel, built at the personal expense of Grand Master Antonio Manoel de Vilhena in 1731. There we heard the Brandenburg Concertos performed by Concerto Köln, who were using not only newly crafted reproductions of baroque flutes (which had a somewhat placid, enclosed sound) but also the pitch used at the court of the Margrave of Brandenburg – a semitone lower than that used by most baroque orchestras and a full tone lower than that used by modern ones.

It was a rather different atmosphere from that I had experienced in the same theatre a couple of days before, when I heard Hippolyte et Aricie ou la belle-mère amoureuse, a puppet parody of the Rameau opera. It was beautifully staged (see picture, top) and performed by musicians and singers from the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles (CMBV) and Teatru Manoel, and it was as winningly silly as the genre suggests: La belle-mère was definitely amoureuse, there was no doubt about that, as she wrestled Hippolyte to the floor. One of the arias was addressed to a passing chicken, who warmed to the role of confidante, if all that clucking was anything to go by . . . .

The English Concert conducted by Harry Bicket, St John's Co-Cathedral, below; and Concerto Köln performing at Teatru Manoel

January 29, 2014

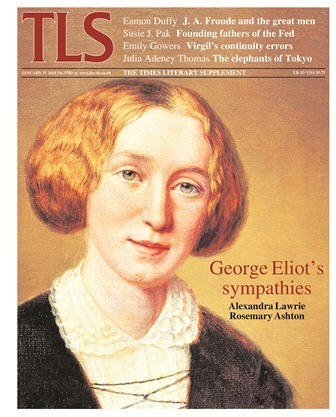

In this week’s TLS – A note from the History editor

It may seem perverse to call a writer “neglected” who is as widely and thoroughly studied as George Eliot. The three books that Alexandra Lawrie reviews this week are testament to the fact that Eliot remains a staple of English Literature departments, and both her life and work will continue to provide material for academic inquiry for decades to come. But as one of the essays discussed by Lawrie asks, why is it that Eliot lags behind other great nineteenth-century novelists when it comes to popular acclaim? If screen adaptations are a reliable barometer, “there have been relatively few reworkings of the novels, at least when compared with the seemingly endless adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Great Expectations”. And of course, “when the Bank of England was casting around for a suitable woman to grace the new £10 note, it was Austen who got the gig”.

In Commentary, Rosemary Ashton revisits a perennial Eliot question: who provided the model for Edward Casaubon, the pedantic scholar whose proposed Key to all Mythologies is out of date because he does not read German? Ashton concludes that the candidate most often put forward was actually a devotee (like Eliot) of German thought, and so not a good fit. The more valuable conclusion is that it is to Eliot’s powers of imaginative sympathy that we should really ascribe her creations.

The three-volume Virgil Encyclopedia, “the first book of its kind in English”, is not quite a key to all mythologies, but it is an attempt to cover “everything of importance that enters into Virgil, that is in Virgil, and that comes out of Virgil into literature, art, and music”. Emily Gowers is not sure how easy a poet as notoriously slippery as Virgil is “to confine, segment and generalize”. Still, “in an encyclopedia, the epic poet’s dream of infinite capacity . . . can be said to come true”.

For those writers who have felt limited even by the ordinary conventions of punctuation, there have been numerous attempts to expand the repertoire of typographical marks, from the “interrobang” to the stand-alone tilde. Sebastian Carter reviews a history of these inventions by Keith Houston.

David Horspool

January 24, 2014

On the road with Raymond Depardon

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts, as it’s not generally known) has always struck me as being incongruously located: an oasis of hipness and cool within a stone’s throw of the Admiralty Arch, Buckingham Palace and the Foreign Office. Just up the steps are Pall Mall and London’s clubland. Its art displays, meanwhile, echo those of the Mall Galleries next door. To feel truly comfortable there you probably need to be well up on your Baudrillard and Fredric Jameson.

It’s currently screening a series of documentaries in its bijou cinema (next week The Armstrong Lie by Alex Gibney, about the disgraced multiple Tour de France winner, and on February 20 ninety bracing minutes of Gore Vidal). This week it was the turn of the French documentary filmmaker and photographer Raymond Depardon who packed his box camera into a large van and set off to parts of the country, such as the Meuse, that he claimed he scarcely knew.

Born in 1942, Depardon has tended to work with his wife Claudine Nougaret, a producer and sound engineer. Depardon has filmed a lot abroad and the 100-minute Journal de France (2012) slightly belied its title by splicing footage from, among other places, Caracas, Venezuela, in 1963, during street protests, brutal mercenary action in Chad, a flag day parade in the newly independent Central African Republic, with the head of state Bokassa looking on proudly (he later declared himself emperor). How, the viewer wonders, did Depardon manage to position himself in the midst of the parade, so that the marchers have to walk round him?

Appropriately we are also granted access to Valéry Giscard d’Estaing who was once involved with Bokassa in some business involving diamonds (anyone remember that?). We see Giscard discussing his presidential campaign with his subordinates, telling them that, having won the first round, the secret is to say nothing and do nothing before the second and concluding round of voting. He won of course.

Jacques Chirac, meanwhile, sports some impressive facial furniture. Did he subsequently have laser eye surgery or did he take to contact lenses? In all his time as president I don’t recall ever seeing him wear glasses. Looking at footage of street scenes from the 60s, I’m struck by just how many people are wearing glasses (and by Depardon’s ability to keep his camera trained on people who are clearly not happy about being filmed or photographed).

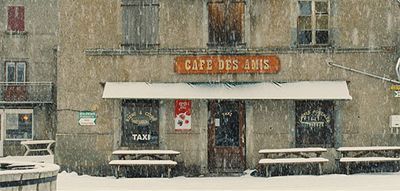

But there is real charm in his work too, not least when he parks the van on the side of the road, sets up his camera and waits for the coast to clear before clicking (how familiar is that feeling: waiting for the intended scene to be clear of cars and people before taking one’s peerless shot?) Maybe it’s just my overwhelming Francophilia but I love ordinary scenes like the one above, in which the subjects reckon they've been sitting there for several decades. They probably have – and why wouldn't they?

January 18, 2014

American Psycho

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Men and women in black and beige trench coats stand in the aisles of the audience singing “we are faceless, perfect faces . . . we are faceless, we are so clean”. Shrieking synths and drum-machine beats: a pastiche of 1980s pop music seamlessly turns into Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” as Patrick Bateman, played by Matt Smith, ascends through a trapdoor wearing tight white Ralph Lauren underpants and a face-pack, all metrosexual and intoxicatingly kitsch.

“This is what Patrick Bateman means to me”, he repeats, along with a list of his toiletries and clothes. He then whips his blazer jacket from its hook on the wall to reveal “last but not least . . . my Walkman. It’s Sony”. We all laugh.

It came as no surprise, last night at the Almeida Theatre, that this new musical adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho worked so well. The story of Patrick Bateman – Wall Street trader, insatiable consumerist, debatable serial killer – couldn’t be more suited to a musical, with its episodes of excess and knowing self-reference. (cf. Martin Scorsese's most recent film, The Wolf of Wall Street.)

The outrage began, of course, before the book was even published, in 1991: the initial publishers, Simon and Schuster, dropped American Psycho (despite paying a $300,000 advance) on the grounds of taste after leaked information about its content – murder, rape, mutilation, torture, misogyny – caused public outcry. James Bowman, in his TLS review, did a hatchet job of his own:

“This is a book about noticing and not noticing things which has managed to get itself noticed . . . . [Ellis] has succeeded, it is true, in the seemingly impossible task of making his book as boring as it is repulsive. But in the end it boils down to the story of a spoiled and vicious child whose complaint that he isn’t noticed enough cannot plausibly be laid to the responsibility of capitalism, Ronald Reagan, the destruction of the environment or even our contemporary ‘moral universe’ . . . but only to that of his sly creator – who now, at least, should be able to get a table at Dorsia”.

Some of the musical’s lyrics are banal (“too much of the things that cost too much”) – but isn’t that the point? It’s the deliberately monotonous libretto of a depraved, unemotional, superficial society. Smith’s deadpan delivery of lines, both spoken and sung, characterize Bateman as blank and hollow: the rhythm and tone of his voice don’t change when he says to a video-shop girl “have a nice day. Have an awesome day”, rendering the words meaningless.

Business cards are the appropriately trivial subject of one of the best songs and scenes in the musical. Bateman and his rival Paul Owen (played by Ben Aldridge) battle in a bar over aesthetics – the thickness of paper, font choice – each trying to prove that his business card is better than the other’s. (It's also iconic in Ellis's novel and in the film by Mary Harron.) Owen naffly dances on a table with exaggerated arms in the air, while Bateman circles him, stalking his prey: "Oh baby, baby, you’re such a card, / making it look so easy, / when you know it’s fucking hard”. "Yours is Times New Roman", Owen scoffs. "I’m no Willy Loman", Bateman replies.

The score mixes new arrangements with 80s "classics", such as Phil Collins’s “In the Air Tonight”, Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me” and Huey Lewis and News’ “Hip to Be Square”, while the slick choreography, visuals and set design recall the era's music videos: hallucinogenic, neon, brash, cubic. One projection looks like Tetris rectangles; in another scene, Bateman has sex with the married Courtney and an almost life-sized pastel pink teddy bear while the rest of the cast act out an aerobics class (with sweatbands, leg-warmers, leotard); in a restaurant, Bateman and his equally odious friends take turns to broadcast their orders to the waitress using a hand-held microphone; and throughout, black plastic strip curtains, like butchers', hang ominously at the side exits of the stage. Such touches are typical of the director Rupert Goold's approach.

The second half brings more of the same, and perhaps the music is less effective because of that. Emphasizing the dark comedy of the novel means that Bateman’s violence and murders are hardly considered as anything other than fantasies, which doesn’t really do justice to the ambiguity in the novel – the terrifying idea that it could all be real. And that we don't know it.

All the same, a transfer to the West End is a safe bet; it really is brilliantly entertaining, and should make – sorry – a killing . . . .

January 17, 2014

Dieudonné and the limits of free speech

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

So he backed down. The French comedian and firebrand Dieudonné (above; full name Dieudonné M’bala M’bala) has been forced to shelve the material he was intending to use for a sold-out tour across France over the next three weeks. The tour went ahead with a gig in Paris earlier this week, but apparently without any overtly anti-Semitic content.

With a show imminent in Nantes last Friday, the Minister of the Interior Manuel Valls stepped in, using all the judicial powers at his disposal to cancel it, in an attempt to break what he described as “une dynamique de haine”. In doing so, he overruled the decision the authorities in Nantes had taken to allow Dieudonné to perform, as they felt a ban would amount to “a serious assault on freedom of expression”, and would therefore be illegal.

But the Ministry of the Interior saw it differently: aside from the “serious risks of public disorder” (I guess that could arise from either course of action – there will be some very angry Dieudonné fans out there), they invoked “a serious attack on the respect due to the values and principles consecrated by the Declaration of the rights of man and of the citizen and by the republican tradition” (it talks of “graves atteintes” whereas the Nantes authorities had “une atteinte grave” – the nuances of the French language . . . ). Interestingly, one poll has shown the French marginally against the actions of the government, although there is overwhelming disapproval of Dieudonné’s stance.

According to Le Monde, Dieudonné’s show contains material that is not only anti-Semitic but also incites racial hatred; the Ministry describes it as an “apology for discrimination, persecution and extermination perpetrated during the Second World War . . .”. Dieudonné has defended Marshal Pétain (not many do that these days), describing him as “less racist than [President] François Hollande”, and welcomed the Holocaust-denying historian Robert Faurisson on stage. He also sings a song called “Shoananas” (“ananas” is a pineapple), so the play on “Shoah” is clear. Having started out on the political Left, he has since flirted with the far Right (he accompanied the founder of the Front National, Jean-Marie Le Pen, on a trip to Cameroon in 2007 – his father is from Cameroon – and Le Pen is godfather to one of his children). The arm gesture he patented, the quenelle, is seen by many as a reverse Nazi salute; he maintains it is an anti-establishment, anti-Zionist gesture. (The French footballer and friend of the comedian Nicolas Anelka recently used it as a goal celebration while playing for the English club West Bromwich Albion – no action was taken against him by the English football authorities. When questioned by French journalists, Anelka used the "anti-establishment" line.)

Clearly Valls’s decision wasn’t taken lightly; all sorts of clichéd expressions come to mind: “slippery slope”, “thin edge of the wedge” etc. But as Le Monde robustly points out, Dieudonné’s utterances are more than mere opinions; they constitute offences (“des délits”) and as such are punishable by law. The paper, incidentally, has been gunning for Dieudonné: it recently published a detailed exposé of the comedian’s complicated financial arrangements. Among other details it revealed that former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad co-financed his DVD and internet film L’Antisémite.

Elsewhere the paper ran an article by Soreen Seelow on the “Génération Dieudonné”, who are mostly young (their opinions therefore matter all the more), left-leaning and claim the right to be able to laugh at anything while denying any taint of anti-Semitism. The Holocaust, for them, is the last comedic taboo while Dieudonné is “the most talented comedian of his generation”. Some complain that they were over-exposed to the history of the Holocaust at school (“we never hear about the Rwandan genocide”), while others, of North African origin, talk “of a hierarchy of racism”: “At school they tell us about Germany’s crimes, but much less about France’s crimes: colonization and slavery. There’s a fear of creating an anti-French feeling among young people from immigrant backgrounds . . . ”. The paper even found a young Jewish male in his audience, who defended the comedian on the grounds that his show constitutes an attack on the “instrumentalization of the Holocaust as described by the American political scientist Norman Finkelstein” – clearly an informed opinion then. But in the same paper a couple of days later Jean Birnbaum expressed the fear that his followers were broadly ignorant and uninterested in history. The Association France Palestine Solidarité, meanwhile, has distanced itself from him, calling him a “political militant of the far Right”.

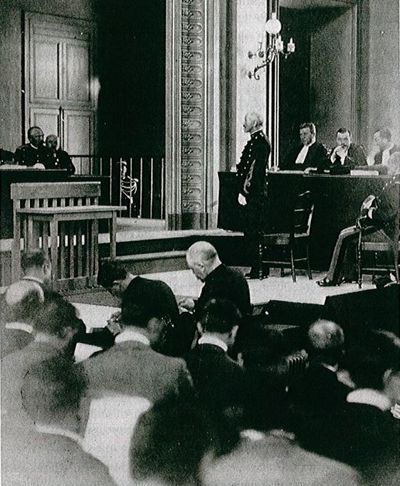

As chance would have it, I’ve recently been reading Robert Harris’s absorbing and well-researched novel, An Officer and a Spy, about the army officer Alfred Dreyfus who was wrongfully convicted of passing on military secrets to the Germans. Although it would be absurd to suggest that the Dieudonné saga has the capacity to convulse, indeed tear apart, the French nation in the way the Dreyfus affair did, crudely pitting Catholics, militarists and monarchists against republicans and those on the Left, there is at least one common thread: Dreyfus was Jewish, of course, as well as being Alsatian (from Strasbourg) and therefore suspiciously German – he even spoke French with a slight German accent.

Alfred Dreyfus (standing) at his second trial, in Rennes, 1899; four years of solitary confinement on Devil's Island have clearly taken their toll (he is not yet forty) – from The Man on Devil's Island

In his acknowledgements Robert Harris thanks Dr Ruth Harris of New College Oxford, whose The Man on Devil’s Island: Alfred Dreyfus and the affair that divided France (2010) he found “immensely useful”. Ruth Harris’s book is a remarkable work, complex, original and illuminating, as well as being deeply researched and wonderfully well written. Among other things, she points out that it would be facile to divide the Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards along Left and Right lines: for instance there were some who “denounced racial anti-Semitism, but still denounced Dreyfus as a means of supporting the army”. But the anti camp were mostly on the right of politics, and the crudeness of some of their rhetoric is still shocking to read.

Harris draws parallels between the Affair and the present. "Today right-wing nationalists keep company with some members of the left outraged by the incursion of religious symbolism into secular education" (this is, admittedly, a reference to the divisive issue of the veil). Nevertheless it seems that today in France, the apparent resurgence of anti-Semitism can be found on the Left as much as on the Right.

Dreyfus himself re-enlisted during the First World War. His granddaughter Madeleine was later in the Resistance. She was deported to Auschwitz where she died in 1944.

January 15, 2014

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

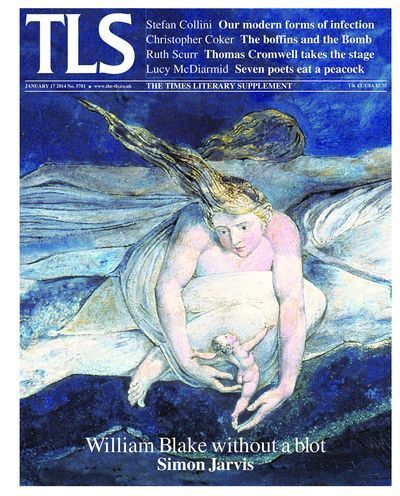

New biographies of two leading figures in English intellectual life whose influence extended far beyond the academy and into politics, R. H. Tawney and Richard Hoggart, prompt our reviewer Stefan Collini to wonder whether “their way” can any longer be “our way” – whether the ethical sensibility and tradition of social thinking they embodied have been permanently undermined by what Tawney identified as the “distinctive modern pathology”: the single-minded pursuit of financial gain. Unfashionable as these two former giants might seem, “it is hard to see how anyone”, Professor Collini writes, “faced with the social destruction wrought by unchecked ‘market forces’ in recent decades, could regard [their] concerns as altogether passé”. Simon Jarvis reviews a “subtle, complicated and counter-intuitive” study of William Blake (pictured) which shifts attention away from that great poet and artist’s radical, revolutionary “enthusiasm”, and maintains a “resolutely agnostic stance on the question of the real extent of Blake’s connections with practical politics”.

For the novelist Jonathan Lethem, politics is personal: “my life was a demonstration”. Lethem’s new novel, Kate Webb writes, develops a critique of the American Left; he “has fun with the drama of revolutionary politics while remaining wary of its self-intoxications”. The America of the Revolutionary War itself is the subject of a book about the leaders on the losing side, reviewed by Mark G. Spencer, and also features in a history of the connections between America’s greatest academic institutions and the transatlantic slave trade – “the American campus stood as a silent monument to slavery” being just one of its “overstatements”, according to George Bornstein. “We dare not America now spurn”, lamented Victor Plarr, a fading minor poet, a few months after he had met the pushful Ezra Pound. And: “The Quack survives when Arts of Learning die, / And every critic learns to cringe & lie!” Pound and Plarr were both guests at the Peacock Dinner, 100 years ago this week: in Commentary, Lucy McDiarmid untangles the insults that were digested along with the peacock.

Alan Jenkins

January 10, 2014

'Drawing the Line'

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Everyone knows that Indian Partition was a very bloody affair, but how many of us can name the man given the responsibility of laying the groundwork for it? In July 1947 Prime Minister Clement Attlee appointed Cyril Radcliffe, a barrister, to the task of drawing the boundary lines between the two new sovereign states of India and Pakistan. There had been riots in the country and the British were looking for as orderly an exit from empire as possible.

The guiding principle, crudely, was that as many Hindus and Sikhs as possible should remain within India’s redrawn borders, while the newly created Pakistan would be home to the majority of Muslims. There was the additional problem of populous Calcutta and Bengal in the East. Radcliffe, absurdly, had five weeks to accomplish this: Independence was set for August 15.

Howard Brenton’s new play Drawing the Line, which has been playing to full houses at the Hampstead Theatre (the curtain comes down with a live-stream performance this Saturday, available on a certain newspaper’s website), focuses on Radcliffe as he struggles with an impossible assignment in a country he has never until now visited, pulled in different directions by representatives from Jawaharlal Nehru’s Congress Party and Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League (at one point he feels inclined to grant all requests to the Sikh representative, purely on the grounds that he has kept silent during an important meeting).

Tom Beard (above, centre, with Nikesh Patel and Brendan Patricks) is excellent as Radcliffe, a decent man in a heavy dark three-piece suit (to keep out the heat?) brandishing a red leather briefcase which he grips firmly, unconsciously perhaps to protect his manhood as he awkwardly exchanges introductory salaams with Nehru’s young aide. We see him struggling with dysentery (some comic touches) and a conviction that he is simply out of his depth. He realizes that there can be no happy outcome however he redraws the map which he is desperately familiarizing himself with, as he holes up in his quarters in the Viceroy’s residence. Mountbatten, the last Viceroy and his boss, tells him that if they can keep deaths down to 100,000 that will be “an acceptable level of violence”.

Mountbatten is nominally neutral but at one point he leans heavily on Radcliffe to urge him to move the line in India’s favour. Brenton dwells – perhaps excessively – on Mounbatten’s chilly marriage with Edwina and her affair with Nehru (nicely portrayed by Silas Carson who, although taller, bears an uncanny resemblance to the statesman), while advancing the theory that his determination to get Edwina out of Nehru’s clutches and back to England hastened the withdrawal from the Jewel in the crown. The whisky-drinking Jinnah (Paul Bazely in a fine performance) instinctively distrusts the British in general and suspects he will not get a good deal.

Brenton is sympathetic to Radcliffe, imagining him, towards the end, on the brink of a breakdown. In what must be a stroke of poetic licence, he seeks inspiration for his actions from the Bhagavad Gita. The real Radcliffe, meanwhile, took the precaution of destroying all his papers before leaving India – were there any repercussions? And in W. H. Auden’s “Poem on the man who drew the lines”,

. . . a bout of dysentery kept him constantly on the trot,

But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided,

A continent for better or worse divided.

The next day he sailed for England, where he quickly forgot

The case, as a good lawyer must. Return he would not,

Afraid, as he told his Club, that he might get shot.

According to Andrew Robinson’s forthcoming India: A short history (Thames and Hudson; to be reviewed in the TLS), the pilot of Radcliffe’s plane (not a boat then) “searched it for bombs” before take-off. Robinson reproduces a letter Radcliffe wrote to his stepson in England on August 13:

"I thought you would like to get a letter from India with a crown on the envelope. After tomorrow evening nobody will ever again be allowed to use such stationery and after 150 years British rule will be over in India – Down comes the Union Jack on Friday morning and up goes – for the moment I rather forget what, but it has a spinning wheel or a spider’s web in the middle. I am going to see Mountbatten sworn in as the first Governor-General of the Indian Union at the Viceroy’s House in the morning and then I station myself firmly on the Delhi airport until an aeroplane from England comes along. Nobody in India will love me for the award about the Punjab and Bengal and there will be roughly eighty million people with a grievance who will begin looking for me. I do not want them to find me. I have worked and travelled and sweated – oh I have sweated the whole time."

In his book The Idea of India (1997), the academic Sunil Khilnani sums up Radcliffe’s letter thus: “It is the weary, fearful, honest pathos of these private words, not the fine public speeches and pomp that accompanied the British departure, that is the true imperial epitaph”.

January 9, 2014

Back in Steel City

By Thea Lenarduzzi

Two men stand smoking on a hill overlooking the sprawling city of Sheffield. Judging by their raincoats and trilbies it is the early 1950s.

“Near half-a-million people live down there”, says one.

“Let’s take a closer look”, says the other.

Cut to silent footage – from the early 1900s – of young men lining up outside a mill, waiting for the taskmaster to give them the nod and the day’s work to start. One gives us the two-finger salute, a four-letter word on his lips. Boys in the forecourt jostle for the camera’s attention.

It seemed far away and long ago to us, as we sat in the plush surrounds of the Curzon Chelsea last night for the premiere of The Big Melt, a film collaboration between Sheffield Doc/Fest and the BBC’s long-running documentary series Storyville. The film combines 100 years of footage from the BFI National Archive, selected and edited by Martin Wallace, with a soundtrack devised by Jarvis Cocker and recorded live at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre last year.

The project, which will air on the BBC on January 26, is ostensibly “about” the steel industry. The opening sequence is drawn mainly from educational videos with authoritative voiceovers describing fire-breathing dragons and rivers of molten ore – but the music brings a very human element to the surface. A rousing string rendition of “Being Boiled” by the Human League (formed in Sheffield in 1977), more mellifluous than the original, accompanies images of the extraction process, all pounding machines and spectacular eruptions. A flute piece – John Cameron’s theme for Kes – is played as a delicate vein of liquid steel pushes upwards like a budding flower.

The connection between Sheffield, steel and music (embodied by the Crucible Theatre which takes its name from a technique discovered in the city in the 1740s), was discussed further in the Q&A which followed the screening. Cocker offered the theory that industrial workers made good dancers – “they had to move to the rhythm of the machines…”. There is a sequence in the film of men dipping and diving on suspension wires during the erection of a bridge, a sort of Fantasia for steel, with the hippos in tutus replaced by slim men in boiler suits. Elsewhere, two men thrust their hips forward and to the right in time, passing a red-hot ingot along the production line. The flipside, Wallace said, is that bass-heavy music took off in Sheffield probably because everyone was deaf from the machinery.

The material in The Big Melt is ordered, cut and selectively repeated so that its different themes gradually emerge: huge bridges are built; brass instruments are played; cutlery forged and shaped. An initially somewhat abstract wave of rivets and bolts which rippled through the clouds in an opening scene finds its place in an animated educational film inviting viewers to imagine “a world without steel”: a man trips up when the garters holding up his socks disappear; his wife struggles to cope as her hairpins vanish; doors fall off as the hinges go, along with the stove, pots and pans. Everything falls to pieces, and the woman's baby is left crying in the wreck of his cot, his nappy unpinned. But then comes the wave, reanimating vehicles that had ground to a halt and fallen apart before a suspension bridge that was no longer there anyway . . . . Thank God for steel, we collectively sigh.

Cut back to the young men queuing, the same footage, but set to a more sombre score; the line-up evokes a different sort of work now. War has come. Women step up, taking steel and transforming it, carefully, tenderly and with visible pride, into munitions that will, hundreds of miles away, undo thousands. A woman’s voice sings huskily about something having gone wrong in the machine – “Some adjustments must be made” – over shots by Jack Cardiff, who was then working as a cinematographer on public information films.

Explicit politics – the strikes of the 1980s, for instance – are deliberately left out to allow for a more meditative experience, a sort of impressionistic reclaiming of the official record. The film was conceived, at least in part, as a work of social history, but, by taking the project back to Sheffield and involving local musicians – from pop stars to school choirs, and the perfunctory brass band – Wallace and Cocker aimed to “drag this archive into the present”. In so doing, they have made something altogether more compelling – in Wallace’s words, “more playful and, at the same time, challenging” – the sort of thing that seems to get less and less airtime on television these days.

Welcome back to Steel City

By Thea Lenarduzzi

Two men stand smoking on a hill overlooking the sprawling city of Sheffield. Judging by their raincoats and trilbies it is the early 1950s.

“Near half-a-million people live down there”, says one.

“Let’s take a closer look”, says the other.

Cut to silent footage – from the early 1900s – of young men lining up outside a mill, waiting for the taskmaster to give them the nod and the day’s work to start. One gives us the two-finger salute, a four-letter word on his lips. Boys in the forecourt jostle for the camera’s attention.

It seemed far away and long ago to us, as we sat in the plush surrounds of the Curzon Chelsea last night for the premiere of The Big Melt, a film collaboration between Sheffield Doc/Fest and the BBC’s long-running documentary series Storyville. The film combines 100 years of footage from the BFI National Archive, selected and edited by Martin Wallace, with a soundtrack devised by Jarvis Cocker and recorded live at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre last year.

The project, which will air on the BBC on January 26, is ostensibly “about” the steel industry. The opening sequence is drawn mainly from educational videos with authoritative voiceovers describing fire-breathing dragons and rivers of molten ore – but the music brings a very human element to the surface. A rousing string rendition of “Being Boiled” by the Human League (formed in Sheffield in 1977), more mellifluous than the original, accompanies images of the extraction process, all pounding machines and spectacular eruptions. A flute piece – John Cameron’s theme for Kes – is played as a delicate vein of liquid steel pushes upwards like a budding flower.

The connection between Sheffield, steel and music (embodied by the Crucible Theatre which takes its name from a technique discovered in the city in the 1740s), was discussed further in the Q&A which followed the screening. Cocker offered the theory that industrial workers made good dancers – “they had to move to the rhythm of the machines…”. There is a sequence in the film of men dipping and diving on suspension wires during the erection of a bridge, a sort of Fantasia for steel, with the hippos in tutus replaced by slim men in boiler suits. Elsewhere, two men thrust their hips forward and to the right in time, passing a red-hot ingot along the production line. The flipside, Wallace said, is that bass-heavy music took off in Sheffield probably because everyone was deaf from the machinery.

The material in The Big Melt is ordered, cut and selectively repeated so that its different themes gradually emerge: huge bridges are built; brass instruments are played; cutlery forged and shaped. An initially somewhat abstract wave of rivets and bolts which rippled through the clouds in an opening scene finds its place in an animated educational film inviting viewers to imagine “a world without steel”: a man trips up when the garters holding up his socks disappear; his wife struggles to cope as her hairpins vanish; doors fall off as the hinges go, along with the stove, pots and pans. Everything falls to pieces, and the woman's baby is left crying in the wreck of his cot, his nappy unpinned. But then comes the wave, reanimating vehicles that had ground to a halt and fallen apart before a suspension bridge that was no longer there anyway . . . . Thank God for steel, we collectively sigh.

Cut back to the young men queuing, the same footage, but set to a more sombre score; the line-up evokes a different sort of work now. War has come. Women step up, taking steel and transforming it, carefully, tenderly and with visible pride, into munitions that will, hundreds of miles away, undo thousands. A woman’s voice sings huskily about something having gone wrong in the machine – “Some adjustments must be made” – over shots by Jack Cardiff, who was then working as a cinematographer on public information films.

Explicit politics – the strikes of the 1980s, for instance – are deliberately left out to allow for a more meditative experience, a sort of impressionistic reclaiming of the official record. The film was conceived, at least in part, as a work of social history, but, by taking the project back to Sheffield and involving local musicians – from pop stars to school choirs, and the perfunctory brass band – Wallace and Cocker aimed to “drag this archive into the present”. In so doing, they have made something altogether more compelling – in Wallace’s words, “more playful and, at the same time, challenging” – the sort of thing that seems to get less and less airtime on television these days.

January 8, 2014

What’s in a difficult name?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I’m glad that Hery Rajaonarimampianina has been newly elected President of Madagascar (with 53.5 per cent of the vote). It’s a tonic for all people with difficult or challenging surnames, and I speak as one.

Before independence from France in 1960 Madagascar was once a kingdom, ruled by the likes of Kings Andriamasinavalona (1675–1710) and Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810). By the 1850s there was a prime minister in office, one Rainivoninahitriniony (also apparently known simply as Raharo). The capital of the island state is of course Antananarivo. I don’t know how these names came to be, but they are wonderfully melodious, aren’t they?

In my case, it might have been easier to have been called something like John Self. My father used to urge me to ask people to pronounce our surname as if they were saying “Tower Hill”, i.e. Towerdin. I rarely acted on his advice – why compound the awkward-name situation by insisting that people pronounce it in a differently difficult way? As a consequence over the years I’ve had everything from “Tahoordini”, “Tahoudini” (that kind of makes sense – Houdini), “Towerdon”, “Touhardini” to people simply not even attempting to pronounce it. It’s never particularly bothered me – maybe it should have. Only in France and French-speaking countries do people generally have no difficulty with it.

The world seems a little short of long- or difficult-named politicians at the moment; at least, few come to mind. Maybe now that he’s out of a Russian jail, Mikhail Khodorkovsky will go into politics one day. But his surname trips off the tongue quite easily. Even Sri Lanka, usually good for long names, is currently governed by the simply named Mahinda Rajapaksa – not a Bandaranaike in sight.

But Sri Lanka has provided some good cricketers’ names over the years: Ranatunga, Jayasuriya, Tillakaratne, Jayawardena, Muralitharan (better known as Murali) – all very fine players incidentally. India, meanwhile, had an excellent spin bowling quartet in the 1970s which included Srinavas Venkataraghavan (he subsequently became an umpire). Unsurprisingly, he is better known as Venkat. Maybe he should run for office.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers