Peter Stothard's Blog, page 50

December 10, 2013

Tindersticks and the painted sky

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Please do not read the lyrics whilst listening to the recordings." Jarvis Cocker has sometimes had to explain why that polite request has appeared in every album by Pulp bar one – the one in which the lyrics were not included. Why print them at all, then? These were albums that seemed to say the lyrics were worth reading (in silence) as well as listening to, a suggestion encouraged by Faber's eventual publication of a selection of Cocker's lyrics as Mother, Brother, Lover, which sets them out with characteristic reverence.

Deprived of the melody that enlivened them, collections of lyrics in print can often seem redundant, inert. Loretta Lynn's Honky Tonk Girl gets round that problem by becoming a kind of biography: it describes her "life in lyrics", the songs themselves being cushioned by reminiscences about being born in "them hills" or entering a talent contest run by Buck Owens ("I entered . . . and won me a watch!"). In a foreword, Elvis Costello describes working with her and turning over a piece of cardboard that fell out of a concertina file labelled "SONGS", and finding one of her most celebrated hits written on the back. The cardboard turns out to have been formerly part of the packaging for an item of underwear – "all that was available when inspiration struck".

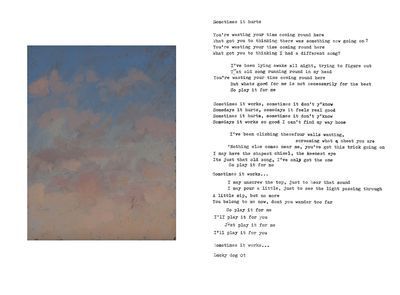

Singing Skies (which appeared earlier this year) is different again, still personal, and rather beautiful. Its creators, Stuart A. Staples and Suzanne Osborne, are husband and wife: a songwriter who doesn't normally write down his song lyrics at all, and a painter who was keen to get back to work after an unproductive period of "stasis".

"Too many songs in my head", the songwriter grumbles in an introductory note to the book by way of explanation for its existence; he went out and bought a typewriter from a junk shop, to clatter out the ones he liked, plus others he didn't, attempting them only once each. So there's a spontaneity to them, which you can see in the vagaries of ink, spelling and spacing, at the same time as some of them are twenty years old.

The painter, meanwhile, for a year from September 18, 2010, undertook daily sky studies, as something that could be carried out wherever she went – anywhere from Istanbul or Limoges to Nottingham or Carlisle. They mainly emerged from her studio in France. As below, the book pairs one of these studies of Osborne's consistently available yet ever-changing subject, with a song by her husband that also ends with a place and a date:

As Stuart Staples says, this seems like a good use for an old song lyric: the processes of painting sky scenes (he watches his wife work "sometimes furiously to catch a moment in a fast-changing sky", tearing off a moment's inspiration) doesn't seem so different from that of writing songs. "I felt they belonged together." Realigned in Singing Skies, words and images seem to contemplate one another, without the connections between them seeming forced.

To extend the experience, you can try reading, say, "Dancing" while occasionally glancing over at the cumulus that happened to be passing that French studio at 6:30pm one October night a few years ago, and listening to Dancing, as recorded many years ago by Staples's band, the mighty Tindersticks. (Some TLS editors prefer to listen to some unstoppable force of narcissism; others like a spot of posthumous revenge; nothing wrong with either, I think, but sometimes it's good to hear something a little more melancholy.) I should have mentioned Tindersticks earlier, perhaps. Because they're the reason this book exists. A great band. A band who have worked with Isabella Rossellini and the French film director Claire Denis. And a songwriter is nothing without all kinds of collaborators, it seems . . . .

December 7, 2013

Dayanita Singh’s museums

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

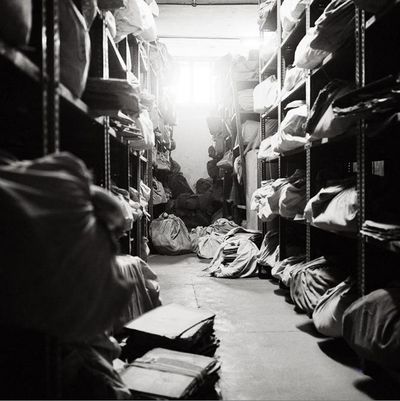

Anyone who has had to confront officialdom or bureaucracy in India will be familiar with backrooms full of dusty ageing files, still present in an age of computers and automation. (Would it be presumptuous to speculate that the bureaucracy is a British legacy, an offshoot of that other parting gift, the civil service?)

The photographic artist Dayanita Singh, who was born in New Delhi in 1961, has admitted to “an obsession with archives”, eloquently expressed in the Museums sequence of her exhibition Go Away Closer, at the Hayward Gallery (until December 15). Archivists, she says, “design their own structures, whether it be metal or wood, and most of the time also design their own catalogue systems. So there is great individuality there, and I love that”.

As the Director of the Hayward Gallery Ralph Rugoff writes in a foreword to the accompanying book, Dayanita Singh has “also chronicled the end of an era in the information age, by photographing bureaucratic archives in India that are filled with piles of disintegrating paper documents”. Geoff Dyer, in his introduction to the book, says of the file pictures, “what cries out to be described as Dayanita’s most ‘substantial’ body of black-and-white work, File Room [is] a documentary record of documents!”

According to the curator of the exhibition Stephanie Rosenthal, “her images are meant to be read, not simply seen; they demand the sort of active looking that engages the mind as much as the eye . . . the images are rarely given captions, since Singh believes that factual information gets in the way of the viewer’s experience of the image”.

"Zeiss Ikon 1996"

There is a poignant sequence of photos of “her greatest friend”, the eunuch Mona Ahmed, who has gone from “being a diva to becoming an outcast among outcastes, living in a graveyard . . . . She asks God, ‘why did you make me like this?’ and tells us: ‘ no one becomes a eunuch by choice. We are not like men trying to be women, we are the third sex’”.

Singh creates “Museums”, beautiful wooden structures, folded like Japanese screens but containing sequences of photographs (nearly all black and white). Thus we have the Museum of Chance, the Museum of Men (which includes a photo of a quizzical-looking Günter Grass in a side street, possibly in Delhi . . .), the Museum of Embraces and so on. Of her Museum of Machines Singh says, “these are not just machines, these are sculptures. There is something organic about them”.

In an exhibition leaflet the visitor is told that the "Museum Bhavan is a collection of museums made by Dayanita Singh. Permanently installed at Vasant Vihar, New Delhi, the museums will, however, travel to other venues . . . . The design and architecture of the museums are integral to the images shown and kept in them. Each large, wooden, handmade structure can be placed and opened in different ways".

For me, the most striking image (not available for reproduction) was that of an indoor swimming pool at night (Singh has talked of working at night, “with the ‘wrong’ film and the ‘wrong’ exposures”), the overhead lights playing on the surface of the black water, while large arched doorways, their shutters pulled back, open on to the darkness outside with a couple of lights in the distance; there are three small starting blocks and, just visible in frame, a diving board. The whole scene is pervaded by a sense of mystery.

Go Away Closer occupies the upstairs gallery of the Hayward. Downstairs are the Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta’s earthy and blood-soaked images, which Judith Flanders reviewed in the TLS of October 14.

December 6, 2013

Stan Tracey at Trinity

One purpose of being a student is to show what a particular student cannot do.

One of many things that, in Oxford in the seventies, I found that I could not do was to be a jazz promoter.

The death tonight of Stan Tracey reminds me of that inadequacy - as well of some leaping, bubbling music, some of which I am playing on Spottify now.

In 1970 I could claim, with only mild exaggeration, to be a young jazz critic. I had won a competition in The Daily Telegraph to write a short piece every month. Stan Tracey was one of my subjects. I wish I could rediscover now the album that I had at that time but Spottify is not as helpful as I need it to be.

But back then, at Trinity College Oxford, we had space, a hall, the money to pay for Stan Tracey. Why should we not offer the greatest British jazz musician to our fellow students?

No reason, I thought.

The first problem came when the maestro came to check the piano.

I was not sure at first that it was Tracey himself. Surely I thought (far too much thinking here) he would have someone else to test his pedals.

But Tracey - then and, it seems, for most of his life - lived and played without the 'people' that is genius merited. In 1970, I discover now from his obituaries, he was close to giving up and becoming a postman.

Our piano, expensively hired and carried into our dining hall though it had been, was no good. The wouldn't-be postman made that very clear, like one of our tutors rejecting the scansion of a Latin line.

A retuning was required - and in those generous financial days was ordered and quickly achieved, albeit at some significant cost to to our margins for profit.

All that remained was to wait for the band to return before the announced time - and for the paying audience to follow.

Tracey was in place precisely as paid for.So were the three other players for the night. The oil-painted college founders beamed down benignly upon the scene.

A band of my closest friends was there too, but only my closest friends, encouraged by the Trinity College Arts Committee's commitment to interval drinks.

At the moment when the music was about to begin a bustle of bearded men (and one woman) arrived, probably not students but who cared or could tell?

They seemed prepared to pay but they needed some questions answered.

Were we offering the Stan Tracey Septet, which seemed to be what they wanted?

Or the Quintet which seemed to be what they were expecting?

Or the Quartet which was going to send them instead to an evening at the White Horse?

The White Horse had a good night.

Mr Tracey played for the agreed time, precisely for the agreed time, took his money and left.

After that I never rediscovered my fiercest enthusiasm for the man who made jazz a British art like no other ever had or has.

An early lesson for me about critics and money-makers and how the two may be resistant to mixture.

RIP to Stan Tracey.

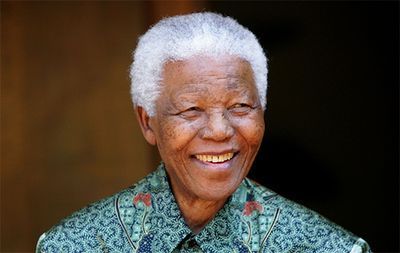

Remembering Mandela

“When I first met him in Johannesburg, when he was in charge of the ‘defiance campaign’ of 1952, he already had a formidable presence”, writes Anthony Sampson in his review of Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom (TLS, December 30, 1994).

Sampson, a British journalist who lived in South Africa for four years in the 1950s and attended the Rivonia trial, published his own biography of Mandela, which Randolph Vigne reviewed together with F. W. de Klerk’s autobiography in the TLS of July 9, 1999: “It was the Robben Island period which formed Mandela the liberator . . . ”.

We remember the extraordinary life of Nelson Mandela.

December 5, 2013

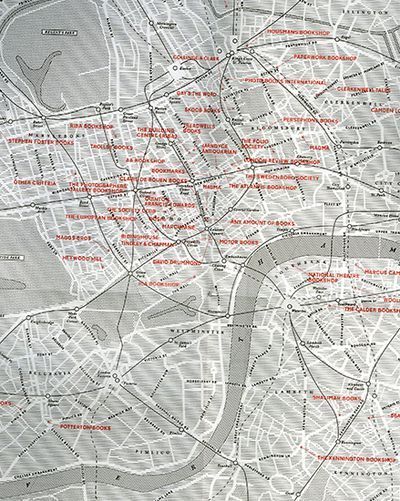

Digital bookshops

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“A young soldier is being treated very harshly by his commanding lieutenant. He is accompanied the entire time by a naked or nearly-naked woman.”

This was a short story I digitally generated before breakfast this morning using The London Bookshop Map App, which has recently been launched. Part of the free iPhone app showcases compressed writing (not unlike our current TLS Twitter competition) collected by the artist Dora García for her on-going project, “Twenty-three million, five hundred and eighty-six thousand, four hundred and ninety stories”.

The app takes snippets of text from García’s previous work, “All the Stories” (in which participants wrote stories up to four-lines long) and then splices them together. Story number “2527” eloquently explains the development of this project: “An artist wants to write all the stories in the world. She meets a cartographer and an inventor. The inventor makes a machine to make old stories new. The new stories are stranger than the originals”.

Some of the resulting lines are disjointed – grammar and pronouns are often questionable – and they can sound like short summaries rather than stand-alone stories. But the idea is exuberant and fun, like a Dadaist or Surrealist experiment, a textual game at the push of a button (“Tell me a story”). You can then view your story in the “logbook” alongside others; each story gives the date and time of creation and a rough location (recent posts come from Vilnius, Zagreb and San Francisco).

Here are a few interesting cross-breeds:

“An employee kills his employer. Well, she didn’t dislike it.”

“In the beginning, men couldn’t talk. He decides to educate him and push him further than he himself was ever able to go.”

“A man decides to leave his wife to begin a new life. He then gets a hand transplant from a mysterious surgeon – and finds he has the impulse to kill.”

“A company develops a robotic sentry to guard the border between North and South Korea. An infinite walk, without purpose, without any sense of direction. But still she is not his wife, and her silence when they make love drives him crazy.”

According to the developers, the main point of the app, other than commissioning and distributing contemporary text-based art work, is to promote local independent bookshops that stock “thoughtful and idiosyncratic choices of books rather than market-driven selections . . . [and] are crucial platforms for alternative publishing”; with García’s project, the app itself serves as a new kind of publishing.

The physical edition of the map which you can pick up, also for free, at independent bookshops has a beautiful graphic design; like a finely inked ordnance survey map of London. But the advantage of the app is that it shows your location and suggests bookshops nearby. You can also filter your search by specialism, such as “Antiquarian”, “Cookery”, “Zines”, "Radical", "Specialist Bindery", "Middle Eastern" and “Magic”. My nearest suggestion for the latter was the Atlantis Bookshop on Museum Street: the app shows you how to get there, gives you the shop’s phone number, opening times and a small description (“Europe’s oldest independent Occult bookshop. Aleister Crowley, Austin Spare, Dion Fortune and W. B. Yeats shopped here. New and second hand books on all aspects of the esoteric sciences, Tarot cards, crystal balls, and regular events”).

It’s a wonderful sort of interactive mappa mundi for bookworms.

December 4, 2013

From wooden O to U: inside the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

By MICHAEL CAINES

Architects and theatrical designers must have this uncanny experience a lot: walking into a space that’s somehow both new and familiar, because it’s both freshly constructed and an echo of floorplans and elevations. Soon, however, all those scholars and admirers of seventeenth-century drama who have found themselves entranced by certain enigmatic drawings discovered several decades ago in the archives of Worcester College, Oxford – drawings once thought to be Inigo Jones’s designs for an early seventeenth-century theatre in London, the Cockpit or Phoenix near the modern Drury Lane – can enjoy something like that experience, courtesy of Shakespeare's Globe.

The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse opens to the public in January with a production of The Duchess of Malfi, with The Knight of the Burning Pestle and The Malcontent, to be played by a company of young actors. It’s the kind of programme that the adjacent open-air space could hardly accommodate nowadays, with its duty to fill the house at the height of every tourist-thronged summer. Exciting though this might be for lovers of pure Jacobean drama, however, it ought to be even more of a thrill for them to see these plays in this intimate, hybrid replica of a seventeenth-century theatre, lit by beeswax candles. It seats just shy of 350 people (including, I guess, that modern paradox of “standing seats”).

It was certainly a pleasure to see, as I saw last week, in the company of other members of the press, how near to completion London’s latest playhouse is. The shell has been there for a long time, but a year ago, after the Globe had returned to its original plans to create an indoor theatre to complement the outdoor one, the auditorium looked something like this:

Now, I can say, it’s in a state much closer to the computer vision of a “wooden U”, complete with musicians’ gallery, ornately limned ceiling and serried candlelabra:

The Jones attribution for the Worcester College drawings might no longer matter as much as it once seemed to (and here’s the persuasive work done by Gordon Higgott dating it to much later in the century and identifying the hand as that of John Webb), but pains have been taken, we visitors were assured by the Globe’s artistic director, Dominic Dromgoole, to ensure that there is a period precedent for every detail here, carved into oak by Peter McCurdy and his team, who built the Globe itself (and over on YouTube you can get a taste of how that process has worked). The effect is apparently quite distinct from that of walking into the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia, though at first glance they might appear to be similar.

The intimacy of the space, too, with the curving rows of seats in the pit seeming to divide their attention between the stage and their counterparts on the other side of a central aisle, and a stage that projects something like halfway into the whole auditorium space, holds out its own promise of the entertainment to come – and something very different from the open-air Globe’s fun with groundlings and sonic battles with the noise of passing air traffic. In fact, somebody told me, the company had already enjoyed experimenting with scenes, lighting and musical instruments; if anything, actors would have to learn how to resist, as well as give in to, the intimacy of the space. In the 1600s, Malfi was first performed indoors, at the Blackfriars, before moving outdoors to the Globe. Being able to walk around the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse as well as the Globe gives you a sense, if you hadn’t already imagined it clearly enough, of just how drastic a transformation that must have been. Does the play exist that could comfortably transfer from one stage to the other without being radically upset along the way?

Personally, I'd be curious to see much more of the old repertoire on this stage, including (although it’s probably not high on the Globe’s list of priorities) some pieces out of the Restoration stock (the Phoenix was still just about in business after 1660). Let's hope the opening season is a sign of things to come.

December 2, 2013

Hitchcock comes home

By Thea Lenarduzzi

There's a scene in Hitchcock's 1939 adaptation of Jamaica Inn in which Sir Humphrey Pengallan's manservant dares to bring up the matter of his master's unsettled accounts. Sir Humphrey's response, delivered with brio by a bloated Charles Laughton, is, "Don't butcher and baker me". It seems particularly ironic given that that is precisely what Hitchock and his team of scriptwriters – which included J. B. Priestley – was doing to Daphne Du Maurier's novel. Du Maurier disliked the adaptation so much that she considered denying the director the rights to bring Rebecca to the big screen the following year. Thankfully, she came round ….

Last night I took the train to Leytonstone again. I was lured there for a screening of that film (and the promise of mulled wine and the first mince pies of the year), part of a Hitchcock season organized by Create London and Barbican Film. Leaving the Tube and heading above ground, a swipe of my Oyster card saw me pass like a spirit through the barrier before me; a colourful display of Hitchcock-inspired murals led the way.

The aim of this year-long season, launched in September with a screening of Vertigo at St Margaret’s Church, Leytonstone, is to reinforce the links between the great man and his suburban birthplace (Leytonstone, Essex, at the time) by bringing “the suspense, adventure and glamour of Hitchcock’s films back to the place that was perhaps their original inspiration”. Part of a programme of events leading up to the opening of the new Empire Cinema next year, the screenings herald the return of cinema to a borough that has been without for ten years.

Last night’s screening was held in Leytonstone School, a captivating example of early twentieth-century mock Elizabethan architecture, all lattice windows and ivy. After trying (like fools) to capture its gothic airs with our mobile phone cameras, we were ushered into the assembly hall where we took our seats, the beams of the building whispering softly of the beeches of Manderley, their “naked limbs leant close to one another, their branches intermingled in a strange embrace, making a vault above my head like the archway of a church”.

The film critic Catherine Bray stood up to introduce the project and the film, a copy of the novel in her hand. Du Maurier described the story, in a note to her eagerly awaiting publisher in 1937, as “Psychological and rather macabre”, an epithet which, Bray suggested, might do just as well for Hitchcock’s own work. Rebecca holds a special place in his filmography; it was the director’s first Hollywood film and, though it was not his first adaptation of Du Maurier’s work, it was certainly his most faithful. This was less a reflection of the novelist’s tight grasp following the Jamaica Inn debacle – she insisted that Laurence Olivier take the role of Maxim de Winter, more polar an opposite of Laughton could surely not have been found – and more a result of the producer David O. Selznick’s if-it-ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it attitude. The novel was after all – and in spite of the reviews (“A lowbrow story with a middle-brow finish”, said the TLS) – a best-seller for a reason.

The ending – that is, the morally dubious happy ending written by Du Maurier – could not, however, make the final cut: the Hollywood Production Code maintained that a crime of the sort committed by Max de Winter – and covered up with the assistance of the “my wife”, “my dear”, “erm…”, played by Joan Fontaine – could not be seen to go unpunished. And it is this version of Maxim we met again last night, played with great charm by Olivier, of course, but stunted nonetheless – a part of him shaved off, the darkest knot carved out.

Mrs Danvers, too, is a rootless figure, sinisterly so. There is none of the maternal psychology of the novel – Judith Anderson who took the role was, at forty-two, considerably younger that Du Maurier’s antagonist. To put it bluntly, the lesbian subtext is to the fore – a lingering close-up on Mrs Danvers’s face as she brushes the heroine’s cheek with one of Rebecca’s furs “You can feel it, can’t you? The scent is still fresh, isn’t it?”.

You will find them all preserved, however, in Du Maurier’s novel, a reissue of which will, I predict, come sometime in the new year alongside a couple of remakes – Jamaica Inn on the BBC; the Hollywood (re)treatment for Rebecca.

But what struck me on re-watching this Rebecca was the humour – and I don’t think it was all retrospective, a result of the mannered dialogue and techniques of the period – and the score, which chops and changes from soaring strings to thunderous drums as quickly as the whirlwind romance between de Winter and “erm” plucks them from Monte Carlo and drops them in Manderley. It is a kind of cinematic hysteria. As Du Maurier said of the novel, “a tragedy is looming very close and CRASH! BANG! something happens”; the speed with which one must move from relaxed laughter at something “you silly fool” has said to the heights of anxiety as Mrs Danvers closes in is dizzying.

There was a round of applause last night – equal parts appreciation and a curious sense of relief that the spell had been lifted – with everyone turning to their neighbour, checking each other’s reactions. When was the last time you clapped at the end of a film (in public, I mean)? A reminder of the power of cinema, for sure, and of the importance of this invigorating project.

November 30, 2013

Before (and after) The Catcher in the Rye

Much attention has been given to the recent oral biography Salinger, in which the claim is made that the author of The Catcher in the Rye carried on writing until his death in 2010. Salinger's last published story – "Hapworth 16, 1925" – appeared in the New Yorker in June 1965. But according to David Shields and Shane Salerno, the authors of Salinger, several completed works exist among the author's papers, of which publication is set to begin in 2015. The work that will be most keenly anticipated is The Family Glass, which collects "all the existing stories about the Glass family, together with five new stories that significantly extend the world of Salinger's fictional family". All five concern Seymour Glass, whose suicide was recorded in the original Glass story, "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" (1948). One "deals with Seymour's life after death". All are said by Shields and Salerno – who haven't read them – to be "saturated in the teachings of the Vedantic religion". Another posthumous work is a manual of Vedanta, "with short stories, almost fables, woven into the text". A full-length novel is thought to be based on Salinger's relationship with his first wife. Should it appear, it will be only his second novel, extraordinary as it seems. It has a wartime setting, as does a new novella.

Fans of the Glass and Caulfield clans will look forward to it all. It is seldom remarked, however, that there already exists a collection of stories by Salinger, not published in the usual sense but available to anyone with access to a computer. "Uncollected Stories" consists of twenty-one tales published in the 1940s, in magazines such as Collier's, Esquire and the Saturday Evening Post. Once, it would have been necessary to go to a major American library to read them, but now you can print them out at your desk. Some are good, and even the earliest have the recognizable likeable touch. Here is the opening paragraph of "The Young Folks", written when Salinger was twenty-one and probably his first professionally published sentences:

"About eleven o'clock, Lucille Henderson, observing that her party was soaring at the proper height, and Just having been smiled at by Jack Delroy, forced herself to glance over in the direction of Edna Phillips, who since eight o'clock had been sitting in the big red chair, smoking cigarettes and yodelling hellos and wearing a very bright eye which young men were not bothering to catch. Edna's direction still the same, Lucille Henderson sighed as heavily as her dress would allow, and then, knitting what there was of her brows, gazed about the room at the noisy young people she had invited to drink up her father's Scotch."

"Uncollected Stories", which sits before us in a 230-page A4 print-out, contains several stories involving members of the Caulfield family, including baby sister Viola – never to be seen again – and Kenneth, who died young. In The Catcher in the Rye, Kenneth appears to have been replaced by the deceased brother Allie (neither makes an actual appearance).

Salinger said of these early stories that he was happy to let them die a natural death. He failed to foresee the internet. Salinger by Shields and Salerno will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

J. C.

November 28, 2013

Turner in Brighton

J. M. W. Turner: “Moonlight over the sea at Brighton”, c.1796

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Mention the name Brighton and the first thing most people are likely to think of is the onion-domed Royal Pavilion. The twenty-one-year-old George, Prince of Wales first visited the pleasure town in 1783 (then boasting a population of 7,000 or so), and in 1787 he asked Henry Holland to convert a farmhouse he had taken a lease on into a neo-classical villa. On becoming Prince Regent in 1811, he commissioned John Nash “to enlarge the building further”, according to the visitor’s brochure. “Between 1815 and 1822 it was transformed into the present Pavilion, with an exterior inspired by Indian architecture” – but without the benefit of the brilliant Indian sun to set it off (the stone can look very dull on a grey day). But the real interest is inside: the orientalist decor, including mahogany handrails made to look like bamboo, and elaborate chinoiserie, the opulent Banqueting Room and magnificent Kitchen, the giddying Music Room, a riot of brilliant colours.

When did Brighthelmston(e) become plain Brighton? In 1769 Boswell wrote of Johnson being “at Brighthelmstone with Mr. and Mrs. Thrale”. Later, Johnson, in a letter to Mr. Robert Levett from Brighthelmstone on Oct. 21, 1776, revealed that he “did not go into the sea till last Friday, but think to go most of this week, though I know not that it does me any good . . . ” (in late October!). By 1779 it was Brighthelmston without the final “e”: “Mr. Thrale goes to Brighthelmston, about Michaelmas, to be jolly and ride a hunting . . .”, Johnson wrote to Boswell on September 9, 1779. In 1780 he was admitting to Boswell “I do not much like the place”.

Turner probably first visited Brighton in 1796. By the time he visited again in 1824 at the age of forty-nine the fashionable watering hole had become the fastest-growing town in England, its population swelled to 24,000. Turner’s rival John Constable grumbled that the beach was “Piccadilly by the sea-side”. Turner was later to say of Constable’s paintings of the sea off Brighton, “he knows nothing about the sea”. Constable spent much of the summer of 1824 on the South Coast whereas Turner appears to have stayed no more than a couple of days that year, recording his impressions in a notebook.

The Royal Pavilion & Museums in January 2012 acquired Turner’s Southern Coast watercolours (at auction at Christies in New York). The works are on display in the Pavilion in a mini exhibition (one room) until March 2014.

Most striking are Turner’s depictions of the Royal Suspension Chain Peer, the first of Brighton’s three peers, which was “intended to overcome the lack of a natural harbour, and to provide a landing stage for larger vessels, especially the steamboats that crossed the Channel to Dieppe”. It “extended out to sea for 350 yards on four platforms with cast-iron pedimented pylons . . . . Eight massive chains were used to stabilise the pier” until “it was destroyed in a storm in 1896” (Brighton is down to one pier now, the second having been almost entirely destroyed in a fire – the fate of all too many piers around the country).

“The Chain Peer at Brighton” (with Pavilion in the centre), 1824

As Ian Warrell writes in an informative brochure to accompany the small show, “the most curious detail . . . is the appearance of the Royal Pavilion. Turner’s pencil sketches reveal that it was impossible to see more than its minarets from the pier. But he wanted to combine all of Brighton’s attractions in one scene. To achieve this he removed the seafront terrace that obscured the Royal Pavilion, and then . . . distorted the position of the palace, suggesting it sits by the water”. In June 1824, the Somerset House Gazette wrote of Turner’s Southern Coast series: “We have no hesitation in saying, that for masterly effect, splendour, and painter-like feeling, on copper, they surpass any works of the same class, of every age and every school!”

In 1828 Turner embarked on a second trip to Rome from Brighton, and a couple of years later sketched in nearby Rottingdean and Newhaven (now a major cross-Channel port). By the 1840s the railway from London reached Brighton, via the Ouse Valley Viaduct at Balcombe (the scene of recent anti-fracking protests), a masterpiece of Victorian engineering (below).

But Turner had by now transferred his preferences from Brighton to Margate, a town which is said to be undergoing a regeneration with the 2011 opening of the Turner Contemporary gallery.

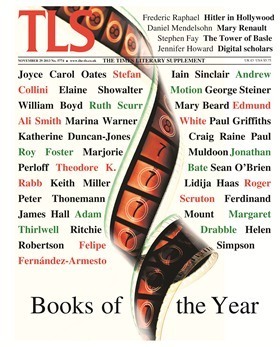

November 27, 2013

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

“Impossible to stifle a whoop of joy on hearing that Alice Munro had won the Nobel”, writes Ferdinand Mount at the start of his selection for our Books of the Year. That is a view, one of many I am pleased to say, in which the previous Editor of the TLS and his successor concur. There is rarely a clear winning choice among our heterodox band of critics but Munro edged her way to first place in 2013 by taking the votes of Beverley Bie Brahic and Ruth Scurr too. It is always good for readers to see on these lists the books that they have already enjoyed: so it was a pleasure for the Editor that at least one vote, that of Jonathan Bate, went to Under Another Sky, Charlotte Higgins’s scholarly travelogue through Roman Britain; and another, that of Roy Foster, for Colm Tóibín’s novel The Testament of Mary. The selections also provide reminders of books intended for reading earlier in the year but somehow forgotten by its end: my sharpest prods are from Margaret Drabble’s choice of Antonio Pennachi’s The Mussolini Canal and Peter Green’s vote for Elizabeth Donnell Carney’s Arsinoë of Egypt and Macedon. Every reader of the TLS, I hope, will find similar pleasures.

It does not seem likely that any of Frederic Raphael’s friends will get a seasonal gift of The Collaboration: Hollywood’s pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand. Why, the author asks, did powerful Jewish movie executives do deals in the 1930s with the most anti-Semitic regime in history? The likeliest answer, replies Raphael, comes in the “old Jewish joke which ends with the tagline ‘Please, do you have another globe?’” Hollywood was for hits; for messages there was Western Union.

Daniel Mendelsohn considers the lifetime attraction to Alexander the Great felt by Mary Renault – a novelist whose time in South Africa led her to the conclusion that less evil was done by conquerors of earlier ages, who needed no moral justification for war, “no need to work up hatred”. Prejudice of a different kind is at the heart of Renault’s reissued classic The Charioteer, which, as Jonathan Keates notes, “was unquestionably fuelled by the author’s anger and despair” at the persecution of homosexuals.

Peter Stothard

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers