Peter Stothard's Blog, page 54

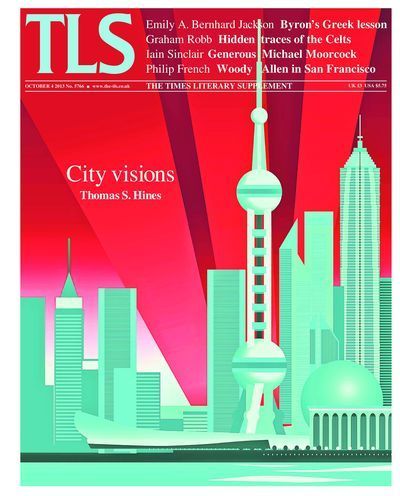

October 3, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the History editor

The human impulse to impose ourselves on our environment has inspired men and

women to build cities, to erect monuments, or to incorporate the animal

kingdom into our own rituals. This week, Thomas S. Hines considers a book by

Daniel Brook that takes four grand urban visions of the future, and sees how

they resulted in “four cities that would come to look and be like no others

in their surrounding cultures”. These versions of modernity all reimagined

western models in eastern settings. In Shanghai, the aim was to create “a

western city that just happened to be in the Far East”, whereas in Bombay –

the name the Portuguese coined, only replaced by the Indian version in the

1990s – the project was directed at the native, not the expatriate

population, to “create a new man who looked like an Indian but thought like

a Briton”. Such epic flights of fancy made victims, from the thousands of

serfs who died to build St Petersburg to the “coolies” on whose backs

Shanghai rose. But they also represented the birth pangs of a mixed, messy

modernity.

In Commentary, Graham Robb reveals a very different record of human

interaction with the landscape, one which, far from transforming it, “for

much of its course . . . exists only as an abstraction, an ideal trajectory

joining various sites”. This is the fabled Via Heraklea, which Robb has

traced on map and by bike. Despite his best attempts to disprove it, the

route also seems to track the angle of the rising sun at the summer

solstice, the sort of discovery that makes a reputable scholar worry that he

is suffering from “historical hallucination”.

Human encounters with the natural world take any number of forms, but it can

be argued that we have assimilated birds into our lives more thoroughly than

any other animal. To English-speakers, as Jeremy Mynott points out, birds

allow us to crane our necks, crow over misfortune or swan around. But

throughout the world, whether in the rituals of the tribes of Papua New

Guinea or the battery farms of Europe, we live with and through birds.

Mynott praises a “major literary event as well as an ornithological one” in

Mark Cocker and David Tipling’s Birds

and People.

David Horspool

October 2, 2013

A real good horrorshow

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

On holiday in the remote mountains of

Mallorca recently, I read Anthony Burgess’s A

Clockwork Orange, and for days

after finishing the book, had a recurring nightmare which involved a person with

a “Peebee Shelley maskie” violently hacking me into tiny, bloody bits. Maybe

I’m easily shocked, but the nightmares are a price worth paying for the experience of reading Burgess’s unexpectedly mind-blowing prose. The incidents that Alex,

the novel's school-boy narrator, describes are shocking; more so because of the book's disturbing language. Here’s how Alex and

his “droogs”, Georgie and Pete, rape a woman and attack her husband, a writer:

“He did the strong-man on the

devotchka, who was still creech creech creeching away in very horrorshow

four-in-a-bar, locking her rookers from the back, while I ripped away at this

and that and the other, the others going haw haw haw still, and real good

horrorshow groodies they were that then exhibited their pink glazzies, O my

brothers, while I untrussed and got ready for the plunge. Plunging, I could

slooshy cries of agony and this writer bleeding veck that Georgie and Pete held

on to nearly got loose howling bezoomny with the filthiest of slovos that I

already knew and others he was making up.”

In the TLS of April 22, 1965 (three years after the original, UK publication

of A Clockwork Orange), Burgess wrote

an article explaining his experimental style: “I wanted to write about possible

ways of dealing with the disease of juvenile delinquency, and I wanted the

story of one young thug’s rehabilitation to be recounted by the patient

himself. This, I thought, called for the use of teenage slang, and I began my

first draft in the coffee-bar idiom (most painfully learnt) of the day. But I

reflected that, by the time the book came out, the slang would already be out

of date . . . . A trip to Russia showed me that stilyagi behaved much like our own (as they were then) teddy-boys,

and I was struck by the notion of fusing the cognate images into one . . . by

manufacturing a composite language, a sort of Anglo-Russian dialect I called

(after the Russian “-teen” prefix) Nadsat.

Conservative by nature, I do not like strangeness for its own sake, and the

fact that my new slang could be justified in terms of a real foreign language

eased my embarrassment at having to write in it . . . . The title of the book

is A Clockwork Orange, taken by some

Americans as avant-garde clever-cleverness but, as any Cockney will know, as

native and traditional as Bow Bells”.

The author’s unfamiliar “slovos”

(words) are especially imaginative when it comes to describing body parts: “litso”

(face), “rot” (mouth), “zoobies” (teeth), “rookers” (arms and hands), “guttiwuts”

(stomach) and “glazzies” (eyes). “Droogs”

comes from Russian drugi, meaning

friends in violence. “Horrorshow”, from kharashó, the

neuter form of the Russian word for “good”, is used as a term of

approbation, like modern slang “wicked” and “sick”. The latter, incidentally,

is also used by Alex to express approval – an unintentionally prophetic stroke on Burgess's part.

For me, one of the best slang coinages is “sinny”

(cinema), apt given the evil Alex is forced to endure through films and also because

of what Burgess was later to feel about Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation, released

in 1971. Burgess thought his novel’s unfamiliar language veiled the violence – nothing

is described outright, he leaves it to the reader’s imagination (which is often

more powerful) – whereas Kubrick’s film starkly realizes the incidents and Burgess’s wordplay is mostly lost.

An awareness of his novel’s potential

to do harm perhaps encouraged Burgess to write a letter to the Editor of the TLS in 1964 defending the work

of his friend, William Burroughs:

“if any writer is likely to rehabilitate an

effete form and show us what can still be done with a language that Joyce

seemed to have wrung dry, it is William Burroughs . . . . Unfortunately, too

many people who should know better protract a squeamishness about

subject-matter that sickens their capacity to make purely literary judgments. I

do not like what Mr. Burroughs writes about; for that matter I do not always

like what I myself write about: I was nauseated by the content of my A Clockwork Orange. There is . . . no

lip-smacking on the part of Mr. Burroughs when he works at the refining of his

raw material into art. Life is, unfortunately, life. Out of life we must

choose, for our writing, what will best stimulate us to write well. ‘Everything

that lives is holy.’ This may not be morally true, but it is true of the

subject-matter of literature. For heaven’s sake, let us leave morals to the

moralists and carry on with the job of learning to evaluate art as art”.

In his autobiography, Burgess suggested poor sales of A Clockwork Orange were probably

down to over-exposure – people didn’t feel they

needed to read the book, especially following the film. Yet Kubrick based his film adaptation on the American edition, which cuts the last chapter where Alex matures and reforms,

and then muses that the next generation will go through the same mayhem of adolescence,

“so it would itty on to like the end of the world, round and round and round”. The

US publishers, W. W. Norton, thought this ending wouldn’t appeal to

American readers; perhaps they didn't get the author’s subtle,

cyclical pessimism. (Burgess only accepted the cut

and the addition of a Nadsat glossary

for financial reasons, but in later reprints, he insisted on reinstating the last

chapter and dropping the glossary.) And another editorial oversight, this time from the English publishers, Heinemann: in

Burgess’s typescript, from which the original 1962 edition was taken,

an editor has written in the margin, “will this name be known at publication time?”, beside “Elvis Presley”.

Why read A Clockwork Orange now? Well, if you don’t, “bolshy

great yarblockos to thee and thine”.

October 1, 2013

Lectured by Leavis

By MICHAEL CAINES

F. R. Leavis had a not-very-soft spot for the TLS, at least in later years. Major or minor, real or imagined, slights and misrepresentations abounded, such as the paper's astounding folly in not welcoming East Coker as a work of heart-breaking genius (in fact, it gave Four Quartets little attention at all), and its general failure to kowtow before the throne of Scrutiny.

The mention of D. H. Lawrence or the incautious glossing of Leavis's views, could prompt a letter of rebuke, dutifully published in the next week's paper; his wife Q. D. Leavis joined in for good measure, once demanding an explanation from the Editor, following an "impenitent and impudent reply" from a reviewer. Then a bizarre, Leavis-baiting error occurred in 1955: a translated History of Switzerland appeared with the claim that he had written the "concluding pages". The publisher's abashed apology for their "printing error" appeared below Leavis's brief yet thoroughly contemptuous reply: "I must ask you to give publicity to the statement that I have never written any pages about Switzerland in any language, and that this use of my name is wholly unauthorized and unwarranted".

Uneasy relations did not prevent the occasional lecture by Leavis appearing in the TLS, but, according to Derwent May in Critical Times, Leavis "went on harassing and haranguing" the paper's mid-century Editor, Arthur Crook, "until the end of his editorship". This was not least because of the rematch with C. P. Snow this paper published in 1970, which returned to the same acrimonious battleground as the "Two Cultures?" debate of a decade earlier, only this time with Leavis throwing in a few "personal barbs", aimed at the Provost of University College London, Noël Annan, for good measure. Leavis almost found himself on the receiving end of a libel action for that. It was averted by Arthur Crook.

Understandably, in 1976, a TLS reviewer could write off Leavis as "our antediluvian polemicist"; and today, you might think, nobody would need to write him off at all. Instead, however, there are signs that interest in Leavis's views on literature, and the place of literary studies in universities, has revived rather than fallen off completely: David Ellis's Memoirs of a Leavisite and Cambridge University Press's new edition of Two Cultures?: The significance of C. P. Snow, with an introduction by Stefan Collini, have appeared this year (and will be reviewed in the TLS shortly); and the University of York holds a conference devoted to Leavis later this month, with an inaugural lecture by Christopher Ricks, following a similar (and most enjoyable) event in 2010. The organizers tell me that there is some serious interest in Leavis abroad, particularly in the Far East, and that there may be more events and publications in the pipeline.

Why the resurgence, if that is what this is? The explanation might lie in the Leavisian qualities identified in a TLS review of 1962, which identifies the wellspring of the critic's admirable qualities as well as his deleterious tendencies:

"As for Dr. Leavis [this follows an account of William Empson's "brilliant and exasperating" Seven Types of Ambiguity], The Common Pursuit contains some of his finest, as well as some of his most irritating, work. The prickly quality, the gracelessness which seems, even to his admirers, to disfigure much of his writing, springs from a genuine and full-blooded concern with standards, with the whole truth as he sees it, which has had a profound if complex influence on most of the younger, critics. . . . Perhaps more than anyone else he has made the rewriting of recent literary history not only desirable but necessary."

The Common Pursuit ends, incidentally, with a chapter called "The Progress of Poetry", which takes issue with a review of W. H. Auden's The Age of Anxiety – a review first published in – well, you know where.

September 27, 2013

Spoons in the Serpentine

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

A white-winged structure swoops

beside a nineteenth-century former gunpowder store in Kensington Gardens. It’s

the new Serpentine Sackler Gallery, which opens tomorrow (a five-minute walk

from the original Serpentine Gallery), and the distinctive design of the architect

Zaha Hadid. She has converted the grade II listed, neoclassical brick building

(“The Magazine”) into a gallery and created a membrane-roofed modern extension to

be used as a restaurant and social space.

“You don’t look forward by

looking backwards”, Hadid says, “you create structures that are adjacent and

juxtapose with historical buildings.” (Last night, the RIBA Stirling Prize 2013 was awarded to Witherford Watson Mann Architects for Astley Castle, a modern home inserted into the walls of an ancient castle.) The extension is certainly a twenty-first-century design. But the dynamic exterior is let down by the inside which feels like an airless white tent. The ceiling stretches high in the

centre; five columns, like upside-down Chinese soup spoons, support the billowing

domed roof and double as sky-lights. These are inspiring shapes, but the edges

of the structure claustrophobically envelop you. Where the roof curves to the ground

at three points, an overhang casts shadow on the cantilevered side-windows (and one

of the larger windows is mostly obstructed by the restaurant’s open kitchen). A

remarkable feature of the Serpentine Gallery is its positioning in the Royal

Park, yet the surrounding landscape is barely visible from inside.

The converted gallery space

is sensitively designed. A light, white cube encircles the two ready-made

vaulted rooms where gunpowder and munitions were kept during the Napoleonic wars.

Raw brickwork and beamed ceilings are exposed here, along with two very small

windows on either end of each chamber. So these rooms are dark, and perhaps

less versatile as display spaces, though they will probably stimulate more site-specific

work from artists.

Adrián Villar

Rojas, an Argentinean artist who is the first to exhibit in the new gallery, has

filled one of these vaulted “powder” rooms with an archive-like collection of

clay sculptures, found objects and living plants (including sprouting phallic

potatoes that nod towards Victor Grippo and the sculptural art tradition). All

are carefully positioned on towering glass shelves lit with brash strip

lighting, as if showcasing a fossilized history of humanity, perhaps from the

past, or perhaps a preserved future age. In the other “powder” room,

Rojas has put stained glass in the two windows, leaving the expansive space empty

and sacred. And throughout the gallery, the floor is covered with loose red

bricks (the whole space smells of damp earth) that beautifully clink underfoot,

and slow your pace, encouraging reflection.

In the white outer-ring

gallery, a huge clay elephant (below) carries a mock-up of the external façade

of the Sackler – is the elephant holding the old building up or is the animal

ramming it down? The same question can be asked of Hadid’s design interventions on the old building.

At the original Serpentine

Gallery sculptures made from raw materials by the Italian artist Marisa Merz also reflect the

fragility of the human condition. One installation, undated and untitled, features

nine clay pin-heads with searching faces on a square paraffin tray. Without any

indication of scale, they could be planets in the universe or stars in the sky.

A feeling of insignificance and anonymity, yet some of the heads flash with gold leaf.

The directors and curators

have thought carefully about the dialogue between Merz and Rojas’s exhibitions.

And an umbilical cord (the “Bridge Commission”) will always link the two

galleries. This year the focus is on literature – every month a new short story,

lasting the five minutes it takes to walk from one gallery to the other, will

be available as an audio download on visitors’ mobile phones. Twelve authors have been commissioned, including Ben Lerner, Adam

Thirlwell, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Luisa Geisler and John

Jeremiah Sullivan; the

first story is by Valeria Luiselli.

The Serpentine is a mushrooming campus

of culture and experimentation. Earlier in the summer I wrote

about Sou Fujimoto’s breath-taking Serpentine pavilion. It was a joy

to walk past it again this week. I don’t think I’ll be saying the

same about Hadid’s extension.

September 26, 2013

French literary anniversaries, part 2

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

French literary anniversaries seem to be coming thick

and fast (and francophobes should stop reading this now). I mentioned last week

(September 19) the forthcoming Proustian landmark in November – more on that nearer the

time. November 7 will

see the centenary of Albert Camus’s birth. And before those two dates we have,

in October, the hundredth anniversary of the publication of

Alain-Fournier’s only novel Le Grand

Meaulnes – an excuse for my second reproduction of a Livre de Poche cover in a week.

As is

well known, the author was killed in action on the Meuse in September 1914 at

the age of 27. Less well known is the fact that a promising fragment of a

second novel, Colombe Blanchet,

appeared in 1990; or that Alain-Fournier lived in Turnham Green in west London

for a while (working in a wallpaper company); or that he changed his name from

Henri Fournier to Alain-Fournier so as not to be confused with the champion

cyclist Henri Fournier; or that it took until 1991 for his remains to be

formally identified.

Le Grand Meaulnes always appears high on any

list of great c20 French novels, and is probably still a staple for lycée students; not everybody was

enchanted by it: Anne Duchêne once

referred to it in the TLS as “that

rather tiresome classic”. I suspect it appeals to adolescent males more than

any other group of readers, but there’s no denying the classical beauty of the

writing. It has that indefinable quality, timelessness.

J. C. suggests

(NB, September 27), in an item on the sixtieth anniversary of the Livre de Poche, that

it’s ”an essential text for the debutant lecteur”.

The arrival in the office of a Centenary Edition (published by Oxford

University Press on October 7, £12.99/$19.95), with an introduction by Hermione

Lee, prompted me to have a look at the available translations.

There

are at least four to choose from: Valerie Lester’s The Magnificent Meaulnes (2009,

Vintage), R. B. Russell’s liberty-taking if occasionally inspired (but poorly

proof-read) version for Tartarus Press (1999), the late

Robin Buss’s 2007 translation (The Lost

Domain, Penguin Classics). And then there’s the new Oxford edition, with a translation

by Frank Davison, which dates from . . . 1959. It was the Penguin edition until

Buss’s version replaced it. Confusing, isn’t it?

Partly out of a sense of loyalty to Robin Buss, who was

a model reviewer for the TLS over

many years, I’m prompted to suggest that his is the best. Buss was a skilled

translator, from Dumas to his near-anagram Camus. Our reviewer David Coward

called his Lost Domain (Buss’s last

translation) “lyrical”, which seems an apt adjective. It’s certainly the most

direct and precise. Davison’s strikes me as broadly eccentric: phrases

such as “an abode from which our adventurings flowed out” don’t really float my

boat, and distort the original: “demeure d’où partirent et où

revinrent . . . nos aventures”. It might

have been an idea to revise it.

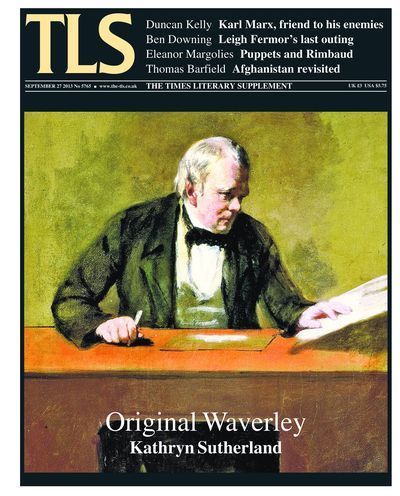

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Managing Editor

Few writers have been so deeply involved in the business of writing as Sir

Walter Scott. Described by Thomas Carlyle as “a Novel Manufactory”, Scott

oversaw a production line employing many hands – amanuenses, house readers,

compositors, and his business partner, James Ballantyne – not to mention the

fictitious “pseudonymous editor-historians” in the novels, and his own later

re-editing of his “grande opus”. This makes the task of reconstructing an

“authentic” version of the Waverley novels a challenging one: Kathryn

Sutherland respects the diligent case-by-case negotiations evident in the

new Edinburgh Edition.

Scott, Sutherland writes, “invented the historical novel in its modern form”.

History creates its own fictions and dramas as it evolves. Thomas

Barfield reviews a number of recent books on Afghanistan, and notes that

a focus on leading figures or dramatic turning points (occupation, surge,

withdrawal) sometimes obscures a messier truth: a world of many actors with

diverse motives, also in need of delicate case-by-case negotiation. Stephen

Lovell reviews 1990, which examines Russian society in a year of

transition, but wonders if that year was a genuine turning point, or just a

useful snapshot from a longer, more awkward transition.

Decades earlier, Russia had withdrawn from Austria, leaving “a symbolic cache

of arms and tanks” as a gift and covert threat. The Austrians reciprocated

by giving the Russians a report from the 1850s made by one of the Austrian

spies who had been monitoring the exiled Karl Marx. As Duncan Kelly points

out, reviewing a new biography of Marx, the fervent Communist was, for some

of the time, an unwitting puppet of his enemies in Vienna.

In Commentary this week, Eleanor

Margolies investigates an intriguing link between real puppetry and Arthur

Rimbaud. Charleville-Mézières, Rimbaud’s hometown, is home to the

world’s largest puppet festival, as well as the Institut International de la

Marionnette; but the connections, Margolies argues, go much deeper than

that.

Robert Potts

September 25, 2013

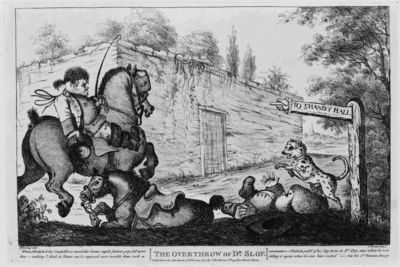

Sterne season

By MICHAEL CAINES

“As my life and opinions are likely to make

some noise in the world, and, if I conjecture right, will take in all ranks,

professions, and denominations of men whatever, – be no less read than the

Pilgrim’s Progress itself – and, in the end, prove the very thing which

Montaigne dreaded his essays should turn out, that is, a book for a

parlour-window; – I find it necessary to consult every one a little in his

turn; and therefore must beg pardon for going on a little farther in the same

way: For which cause, right glad I am, that I have begun the history of myself

in the way I have done; and that I am able to go on tracing every thing in it,

as Horace says, ab Ovo.”

The author of “this humorous rhapsody” did not,

of course, come to the birth of his hero, Tristram Shandy, until three volumes

into his great work – but Laurence Sterne himself was born on November 24,

1713, three centuries ago – so a season of suitably quixotic celebrations is

about to begin.

Up at Shandy Hall, the house in Coxwell that

Sterne moved into the year after the publication of the first two volumes of The

Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, the celebrations began a while

ago, but they continue this Friday with an “educational event” on how to get

drunk eighteenth-century style. They continue in York Minster with Voice from

the Pulpit on October 14, inspired by Sterne/Yorick’s final sermon, with the

premiere of a new work by David Owen Norris – there’ll be a different

educational element on that occasion, in that four school choirs are due to

participate.

Closer to the tercentenary itself, on November

20, there’ll be a “Shandyfest” at King’s College London, involving “talks,

performances, ingenuity and fun”, and, it’s a fair bet, some laudatory remarks

from the usual corners of the newspapers.

As people and Penguins (Penguin Classics, that

is) like to point out, Samuel Johnson seemingly got it wrong when he said that Tristram

Shandy was an oddity that would not last; the coming commemorations show

that it’s “lasted” long enough to still be read around the time of Sterne’s

300th, and recognized as an ancestor of certain experimental, playful

approaches to storytelling. Eminent admirers include Marx, Goethe and that

other novelistic devourer of encyclopaedic knowledge James Joyce.

Suitably quirky forms of admiration would

include Shelley taking the adjective “Slawkenbergian” from Sterne’s “great and

learned” authority on noses (one of the many mock-authorities mixing with real

ones throughout the book), to describe the “prodigious” conk of somebody he

disliked. “I, you know, have a little turn up nose”, he added, “Hogg has a

large hook one but add both of them together, square them, cube them, you would

have but a faint idea of the nose to which I refer.”

You can find Leigh Hunt, meanwhile (or in my

case via Dr Bowdler’s Legacy by Noel Perrin), carrying out a “chastening”,

as he called it, of Sterne for his Classic Tales, Serious and Lively in

1806. Knowing full well what Sterne was sometimes getting at, but comically

disguised for the broader humour of his contemporaries, Hunt could only bring

himself to include “three snipped-up passages” from Sterne in his five-volume

publication. Hunt’s selection, devoid of “vulgar sportiveness” was still doing

the rounds, according to Perrin, at the end of the century.

Can a whiff of that wariness still be detected

as late as 1927, when Herbert Read, writing in the TLS, called it “odd”

that A Sentimental Journey “should have had to wait for the 796th place

a popular reprint of the classics”? Even better, perhaps: Sterne doesn’t

feature at all on a list of the “hundred best novels” (of which more soon, I

hope) as they appeared to a literary critic in 1898. Imagine having room on

your shelf for Black but Comely by G. J. Whyte-Melville and The

Collegians by Gerald Griffin but not Tristram Shandy. (Of course, the

modern shelf has room for all three . . . .) And even now, as one critic

observes, is Sterne “better known read”?

Enough of these “whiffling vexations”. Here’s

what the late David Nokes had to say about how Europe received Sterne’s magnum opus, among other works –

beginning not ab Ovo, but with Marx’s imitation of Sterne, and ending

with a disquieting return to Johnson’s dismissal.

“–and so the chapter ends.”

September 19, 2013

Anatole France and Proust

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

A new translation of Anatole France’s

novel Les Dieux ont soif is being

published next month by Alma Classics, as The

Gods Want Blood. First published in 1912, the book is set during the Terror

of 1793–4 and features, fleetingly, both Marat and Robespierre. As its

translator Douglas Parmée

writes in his introduction, the novel has contemporary resonance: its main

character, the mediocre painter (pupil of Jacques-Louis David) and

revolutionary fanatic Évariste

Gamelin “would surely make a first-rate suicide bomber”. France did his

research thoroughly, with the result that his novel, in Parmée’s words, “bears

throughout the stamp of historical authenticity”.

The publication seems timely: the

elegant, epicurean Anatole France counted among his admirers one Marcel Proust,

whose work celebrates a rather significant anniversary this November. The first

part of his great novel, Du Côté de chez Swann, was published in

November 1913. Proust had devoured France’s work. In her recent Monsieur Proust’s Library

(which I reviewed in the TLS earlier this year), Anka Muhlstein wrote “France’s “style and interests are very similar to the

ones attributed to [Proust’s] fictional writer” Bergotte.

She also pointed out

that “When he was still in school, Proust admired France with a passion that

recalls the Narrator’s at that age for Bergotte. Although he did not know him,

he wrote Anatole France a veritable fan letter after reading a nasty review of

one of his books”. One of Proust’s biographers Jean-Yves Tadié reveals that

Proust “went so far as to plant real France sentences in passages of Bergotte’s

prose”. France wasn’t of course the only model for Bergotte; it’s been

suggested that he was a composite of France, the orientalist novelist Pierre

Loti and John Ruskin – and let’s not forget that the novelist’s own powerful imagination

was at work.

France wrote a brief, rather perfumed preface for

Proust’s early publication Les Plaisirs

et les jours (1896), a collection of stories, poems and observations:

“Marcel Proust delights equally in describing the desolate splendour of the

sunset and the agitated vanities of a snobbish soul”. He noted the author’s “marvellous

spirit of observation, and a supple, penetrating and truly subtle

intelligence”.

According to Muhlstein, Proust’s “enthusiasm for

France’s work . . . waned over the years”, but “their friendship endured,

strengthened by their common fight for Dreyfus”. Later France was to write of

the younger novelist, “I’ve tried to understand him, and I haven’t succeeded.

It is not his fault. It’s mine”.

The new translation of Les Dieux ont soif will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

September 18, 2013

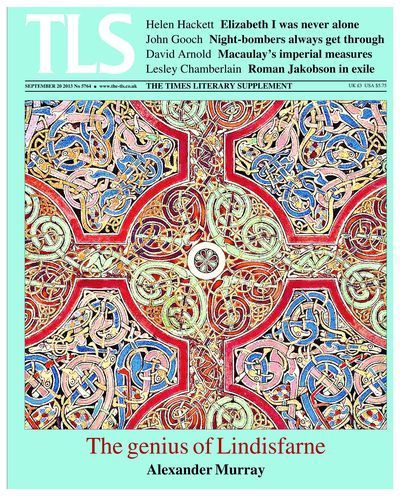

In this week’s TLS – A note from the History editor

The sumptuous book now known as the Lindisfarne Gospels led a peripatetic life

in the two centuries after its creation, but it rarely travels these days.

It has survived in near perfect condition (minus original binding) for

around 1,300 years, and as Alexander Murray writes, its conservators at the

British Library have decreed that “no page may be exposed more than once in

five years or for more than three months at a time”. But Durham, the city

with which it was long associated and where, up until the Dissolution of the

Monasteries, it resided, is a special case. The book has been lent out to

feature as the main attraction in an exhibition at Durham University’s

Palace Green Library. The show not only displays some of the masterpieces of

early medieval art but, as Murray finds, does so “in the highly instructive

company of related manuscripts and artefacts”.

Luckily, the Lindisfarne Gospels avoided the fate of many other early English

treasures, of being looted by Viking raiders. But war has always made

cultural casualties. In the case of the air war over Europe, it was long

argued that Allied attacks on places of cultural rather than military

significance, such as Dresden, were responses to German escalation of the

air war to include attacks directed at civilian morale as well as materiel.

Reviewing Richard Overy’s impressive history of The Bombing War,

John Gooch concludes that, on the contrary, “we started it”, switching the

focus of raids to “heavy material destruction in large towns” in 1940. This

was a case, Overy argues with an Orwellian flourish, of “pre-emptive

retaliation”.

If that overturns one widely held misconception about Germany, a much more

curious feature of German life is the subject of a book by H. Glenn Penny,

reviewed by Peter Pfeiffer. The Germans have a long-held affinity, it turns

out, for Native Americans. Evidence for this comes not only in the form of a

history of self-identification traceable back to Tacitus, but in some of the

most popular German books and films, particularly those of Karl May,

featuring “Old Shatterhand” and his Apache friend, Winnetou.

David Horspool

September 17, 2013

Turning Japanese

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

While on a trip to Japan in the early 1980s, the President of the United States, Jimmy Carter, made a pun.

After a short hesitation his interpreter translated the witticism into Japanese. The Japanese audience burst into excessive laughter, which later prompted the President to ask

the interpreter what exactly he had translated. Was his pun really that humorous? The interpreter admitted that, instead of attempting to translate the pun, he had simply said in Japanese: “the President

of the United States has made a pun. Please laugh”.

Here lies a crucial problem in

translation: how do you translate idiom and wordplay? Last night Sandra Smith (Irène Némirovsky's English-language translator) treated us to the anecdote at a Royal Society of Literature talk on translation, chaired by Adam Thirlwell (whose most recent book Multiples, reviewed in this week’s TLS, collates 12 stories, translated in and out of English and 17

other languages by 61 authors). Also in attendance were the writer and francophile, Julian Barnes,

and the novelist, Ali Smith.

The discussion began with each providing a previously prepared translation (i.e. subjective interpretation) of Nicholas

Chamfort’s aphorism, “Vivre est une maladie dont le sommeil nous soulage toutes

les seize heures. C’est un palliatif; la mort est le remède”. Their translations differed markedly in voice and style. Some were

freer than others; some focused on retaining the rhythm and balance of the sentences.

(Thirlwell finally revealed Samuel Beckett’s translation: “sleep till death / healeth

/ come ease / this life disease” – as Barnes commented,

Beckett had gone “quite biblical”.)

Apart from the more obvious challenges of translation

(including whether a translation corrupts the original text), interesting ideas were raised about the dialogue between an

author and translator. How much influence should an author have over their

translation? “I’m just flattered they’re bothering to translate my work in the

first place”, said Ali Smith. But all agreed that a good

translator taps into a country’s culture, adapting the author’s style to allow the work to resonate in the new language.

Translations are part of a text's afterlife; just as a reader’s interpretation is an ongoing process, no particular translation can ever be ultimate and complete (texts ought to

be translated at least every 50 years as readers and languages evolve, it was agreed). Ali Smith referred us to Muriel Spark’s poem, “Authors’ Ghosts” (2004), in which the

speaker suggests that dead authors “creep back / Nightly to haunt the sleeping

shelves / And find the books they wrote” and “put final, semi-final touches, /

Sometimes whole paragraphs . . . How otherwise / Explain the fact that maybe

after years / have passed, the reader / Picks up the book – But was it like

that? / I don’t remember this”.

Thirlwell talked about the

first time his novel Politics (2003) was

translated into Swedish. The translator asked him about specific words, such as

his use of “grandmother” – did he mean the character’s maternal or paternal grandmother? There are precise words for both in Swedish, but Thirlwell had no idea. He thought about it and gave an answer. And so his novel became more realized in its Swedish version.

The title of a book often poses the

most difficult challenge for a translator. Ali Smith’s recent novel There but for the (2011) has proven especially

hard. And so she allowed her translators to drift away

from a too literal translation of her words. It seems there are no rigid rules for translation.

After all, as Julian Barnes forcefully argued towards the end, you would never give Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary

the title Mrs Bovary in its English incarnation.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers