Peter Stothard's Blog, page 56

August 21, 2013

A hooptedoodle or three

By Thea Lenarduzzi

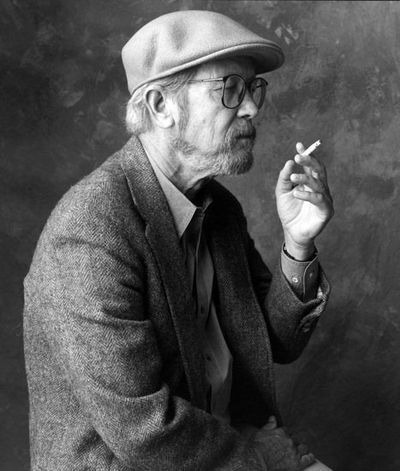

Elmore Leonard c.1990. Copyright: Marc Hauser Photography Ltd/Getty Images

Following the death of Elmore Leonard, the internet has been awash with articles on “The prolific US crime writer . . . author of such books as Get Shorty, Maximum Bob and Out of Sight” , “Elmore Leonard, the legendary crime novelist and screenwriter, who wielded sharp prose and created quirky misfit characters”, “Elmore Leonard, the writer of gritty crime novels who was as prolific in his output as he was pithy in his widely celebrated prose” – and other pieces riffing on the sort of “prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword”, described by Leonard in an essay on writing, in the New York Times. (None that I have come across so far draws on the weather for atmosphere, though the Washington Post’s opening line, “Sad news this morning …”, might have raised a wry smile from the proponent of showing not telling.)

Leonard’s observance of rules 8, 9, and 10 in his New York Times piece about his methods for “remain[ing] invisible when I'm writing a book” (“Avoid detailed descriptions of characters”; “Don’t go into great detail describing places and things”; “Try to leave out the part that the readers tend to skip”) led to the pared-down style that set him apart – “Your prose makes Raymond Chandler look clumsy”, Martin Amis is reported to have said.

In Leonard’s prose, too, it was the dialogue that carried most weight and, fittingly for a writer whose aim was to be invisible in his work, an important contribution comes in the form of what others – critics and fans – have said about him.

There is more “hooptedoodle” – Leonard’s borrowing from Steinbeck to describe a writer’s “flights of fancy” – in some of these reviews than in others. (It was not until Unknown Man No 89, in 1977, that the TLS started reviewing Leonard’s work; by then he had written twelve novels, many of which had already been adapted and re-adapted for the big screen, as well as countless short stories. So there was some catching up to do.)

At the time of his death, Leonard was “very much into his 46th novel….working very hard”, so it may not be too long before more hooptedoodle comes our way. Until then, we offer this selection from our archive:

A review of Unknown Man No 89, October 1977

Michael Wood's Elmore Leonard round-up, from December 1986

A review of Maximum Bob, from September 1991

A review of Rum Punch, from October 1992

A review of The Tonto Woman and Other Stories, from October 1999

Stephen Abell on The Complete Western Stories, from June 2006

J. C. on Elmore Leonard's "10 Rules"

A review of Djibouti: A Middle East Western on water, from April 2011

August 20, 2013

Just a reminder

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's around this time of year that we receive calls from puzzled subscribers, wanting to know what's happened to their copy of the TLS. Has it got lost in the post? Has their subscription lapsed? Are we deliberately withholding it for fear of what they'll read on page 32?

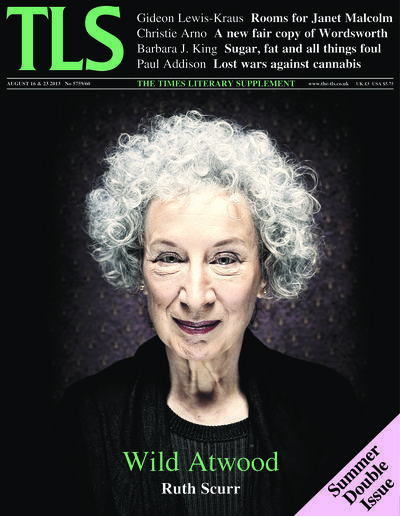

The query is understandable – this is a weekly publication for weekly people, to mangle a phrase from The League of Gentlemen. Twice a year, however, in August and at Christmas, we publish a "double" issue (which last week managed to cover everything from Margaret Atwood to Angela Merkel, Janet Malcolm, obesity, poetics and garden gnomes), making the total number of issues per year fifty rather than fifty-two. If this is no concern of yours, please forgive this minor piece of housekeeping; but if you're a reader looking forward to a TLS for August 23, please be aware that it's already out there, in the form of the TLS for August 16 & 23 . . . .

NB: Two years ago, the image above, of an imagined meeting between Marcel Proust and Henry James, is what you would have seen on the cover of the TLS after the summer double issue. (The inspiration being this piece about literature and the mind by Gregory Currie.) They don't appear to be enjoying one another's company, do they? Suggestions for what M. Proust is saying – or James is, unspeakably, thinking – are welcome.

August 14, 2013

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

We should perhaps not be adding to the discussion of obesity at this time of the year. The evidence on the summer streets and beaches is reminder enough of what men and women can do to their bodies or, as Barbara J. King describes this week, what the food industry has too often cajoled, encouraged and bribed them to do. King is reviewing three books that show, in different ways, how sugar, salt and fat make us want to eat sugar, salt and fat. A cycle of desire connects “allure” and “bliss points” and can send consumers “over the moon”. Every food problem is a food industry opportunity. Parental fear of processed meats leads to three-year-olds beating a billion-dollar path to a place where, at some summer in the future, they will not want to be.

BlyssPlus pills and the murkier content of minced meat have already played a part in Margaret Atwood’s dystopian sequence of novels that began in 2003 with Oryx and Crake. Ruth Scurr recalls the SecretBurgers chain, in which cat fur and mouse tails are just some of the problems for consumers in the “pleeblands”. MaddAddam, the latest volume, is acclaimed for its bleakness, humour and intelligence, and its success at “enacting the transition from oral to written history within a fictional universe”.

Obesity is only one of many nasty traits passed down the generations. Andrew Scull considers the peculiar desire that our children should repeat our own lives, the paradox by which, though many of us take pride in how different we are from our own parents, we are “endlessly sad at how different our children are from us”. He is reviewing Far From the Tree by Andrew Solomon, a collection of “wrenching, often heart-breaking” cases in which parents confront various differences – dumbness, dwarfism and dyslexia – for which life has left them unprepared.

In Renaissance Florence it was fashionable to decorate gardens with statues of dwarves. Later came the ornamental hermits and the garden gnomes; all of them, as Jennifer Potter says, “great dividers of taste”.

Peter Stothard

August 12, 2013

Soapbox sitopia

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Running

alongside the Royal Academy of Art’s new exhibition on Richard Rogers, artists,

designers, architects and writers are arming themselves this summer with a microphone

and a wooden soapbox to speak about the issues confronting contemporary

architecture and cities (if you follow the RA’s twitter account you’ll have

noticed the numerous, contentious conversation-starters they’ve been feeding us

lately “live” from these talks).

Audience

participation, they told us at the start of the fifteen-minute discussion on

Friday, is key; but there were only a handful of polite contributors, no fiery

hecklers – a shame. Perhaps the “free, no booking required” talk (only to those who had bought a ticket to the Richard Rogers exhibition) held at the Burlington

Garden gallery would have engaged more public scrutiny had it been in the RA’s

courtyard, and really open to all . . . .

What

would it be like to describe a city through food? This was the question posed by the architect and writer Carolyn Steel at the end of last week, based on her

book Hungry City: How food shapes our lives (2008), which won the Royal Society of Literature

Jerwood Award for Non-Fiction. Her last chapter coined the word “sitopia”, from

the Greek “sitos” (food), to mean an evolving utopia with

food at its centre. After all, she argued, food is a way of thinking, seeing

and changing cities, “a tool to understand the city as an organism . . . and for

dwelling in a holistic way. We need to ask ourselves how we live”.

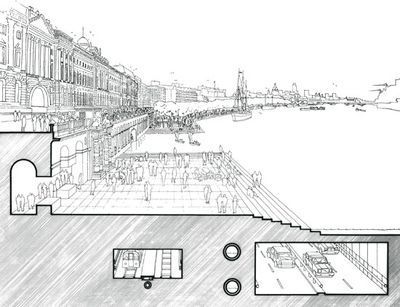

"London As It Could Be", 1986, Richard Rogers Partnership.

"London As It Could Be", 1986, Richard Rogers Partnership.

The ecological loop of a city can be

mapped through food (its production, use, waste etc.). A huge influence on

Steel’s thinking is George Dodd’s book (and no doubt his extensive subtitle) The Food of London: A sketch of the chief

varieties, sources of supply, probable quantities, modes of arrival, processes

of manufacture, suspected adulteration, and machinery of distribution, of the

food for a community of two millions and a half (1856). While lecturing in

Cambridge during the 1990s, Steel discovered that her students intuitively

understood the importance of sustainability in architecture when she related it

to food. “If there is food in the middle of a table of people, we all know how

to behave, how to share, how to respect each other’s needs around us.”

Can this food-thinking be applied to how

we create and inhabit space? She has a point. Architecture should address the

humanness of a space, and not only for environmental reasons (good architecture

does both). Buildings, cities, public spaces – these are all intense places for

human interaction.

Around the gallery, quotations from Richard

Rogers stamp the wall in bold, black lettering on bright (those iconic Rogers

colours) poster-like backgrounds: “good design humanizes. Bad design

brutalizes”; “the concepts of citizenship, civil society and civil responsibility

were all born in the city”; “architecture plays a vital part in humanizing

cities, structuring the scale of spaces and buildings, and shaping an

environment that encourages justice, fairness and delight” – snippets

from his BBC Leith Lecture in 1995 (published in the book Cities For a Small Planet).

Another block of colour states “The

Ephebic Oath” – “I shall leave this city not less but more beautiful than I

found it” – apparently it was sworn more than 2,400 years ago by the young

people of Athens (a world city at the time) as they were formally inducted as

citizens.

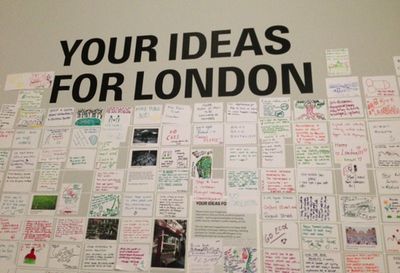

Elsewhere on the walls are “Your Ideas For

London” (above) – a selection of A6-sized notes written by the public, some serious,

some not. My favourites include “use empty buildings” (a thoughtful, ecological

idea for housing a growing population and the importance of a building’s legacy);

and “make a massive spoon swimming pool that sits on top of the Thames . . .

and make it heated”.

In light of Thomas Heatherwick’s plans for a tree-lined pedestrian

bridge across the Thames, a spoon swimming pool doesn’t seem too far-fetched.

And I’m sure Carolyn Steel would be pleased with a cutlery-shaped urban structure.

August 7, 2013

A graphic Somme

By DAVID HORSPOOL

We're bracing ourselves at the TLS for a barrage of books on the First World War, as publishers scramble to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the outbreak of hostilities next year. Being impatient types, many of them have decided to release their volumes a year early, and not just those that focus on the last year of peace in their time ('1913' by Florian Lillies, or '1913' by Charles Emmerson -- doesn't JC offer a prize for this sort of thing?). Max Hastings, Saul David, Allan Mallinson and Margaret Macmillan all have books coming out over the next months, which will be scrutinized, and perhaps even reviewed, as they arrive. Next year, Mark Bostridge, the biographer of Florence Nightingale, will be publishing a study of England in 1914.

Originality is at a premium when it comes to this subject, so another arrival here is most welcome: the graphic novelist Joe Sacco's "illustrated panorama", The Great War: July 1, 1916, The First Day of the Battle of the Somme (Jonathan Cape, £20). In 24 black-and-white plates, printed on a continuous sheet of "accordion fold" paper, Sacco depicts the preparations for and eventual horror of the bloodiest day in the British Army's history, with 20,000 deaths among 60,000 casualties. To give an idea of the impact of the book, as we move from the order of HQ and the massing of troops to the chaos of battle, I tried stretching it out and filming it. Apologies for the quality, but you get something of the atmosphere of this twenty-first-century Bayeux Tapestry, which is accompanied by an author's note explaining each plate, and an introductory essay by the historian and biographer Adam Hochschild.

In this week’s TLS – a note from the History editor

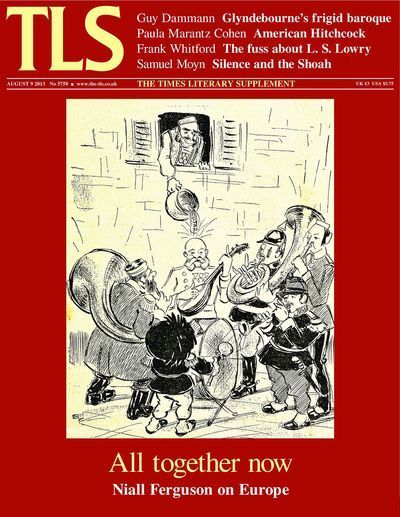

Not too long ago, the cartoonist’s joke shown on this week’s front cover would

have been a familiar one. Here is the “Concert of Europe”, making a filthy

racket, as the Great European Powers attempt to find harmony in the

political settlement that followed the Congress of Vienna. By the time the

Italian artist was working in 1913, this balance had lasted, after a

fashion, for almost 100 years, but was, of course, about to be shattered for

ever. Niall Ferguson welcomes a book on Europe that reassesses such

unfashionable matters as diplomatic history and the relations between great

powers. Brendan Simms, he writes, is “challenging a set of assumptions about

history that came to dominate the academic world in the generation after A.

J. P. Taylor’s”, and he does so in pithy, controversial style that bears

comparison with the master.

In a focus on the Performing Arts this week, our reviewers discuss two

examples of wholesale reinterpretations of classics. Peter Brook has spent

decades restaging Shakespeare, taking his inspiration from sources as

diverse as Norse myth, Kabuki, the Chinese Circus, and painters such as

Breugel, Bosch and Watteau. His Reflections on Shakespeare, John Stokes

finds, show that at the age of eighty-eight, Brook is still thinking

unconventionally about the Bard. At Glyndebourne, the modern operatic

convention of bizarre staging is firmy adhered to, with Rameau’s stately

measures being sung from the interior of a kitchen appliance. Guy Dammann

takes this “designer-garish” setting in his stride, and finds it “faithful

to the baroque spirit”.

In Arts, Frank Whitford discusses the “most popular painter in Britain” (apart

from Rolf Harris), and argues that, contrary to received wisdom, L.

S. Lowry was no amateur “Sunday painter” (he studied for two decades at

Manchester and Salford) and he often strayed from his “home territory”. Nor

was he “neglected”: he was an official war artist and artist at the

Coronation, as well as a Royal Academician. He was also offered a

knighthood. But was he any good?

David Horspool

August 5, 2013

Children’s books: whose pick?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

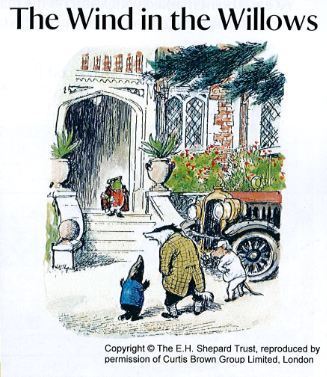

There’s a nice mini exhibition of E. H. Shepard’s illustrations for The Wind in the Willows at Nymans, a

National Trust house in Handcross, West Sussex. The house previously belonged

to the Messel family, originally from Darmstadt in Germany. Shepard was a

friend of the family and visited Nymans in the early 30s, and may have found inspiration from those visits to the house.

The Times, in its mania for

lists (see my recent post on Waugh in Chagford), recently compiled one

of “The 50 books that every child should read”, in which The Wind in the Willows came 3rd. I have to confess that

when I reread the book not so long ago I found it rather disappointing:

meandering to the point of tedium. But that’s by the by. These lists, on this

occasion the work of seven experts on children’s literature, cry out to be picked

apart, of course.

My first objection would be to the word “should”: says who? It

smacks of the “this will be good for you even if you don’t enjoy it” mentality;

I only say this because I took soundings close to home and came up with an

alternative list of books (so I’m doing it now . . .): absent, wrongly in my view,

were The Call of the Wild by Jack

London, Charlotte’s Web or The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White,

Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, Walkabout by James Vance Marshall,

anything by Lauren St John, Michael Morpurgo, Enid Blyton (yes, I’m afraid so –

golly!), the Lemony Snicket books, Cornelia Funke and – weirdly – Hans

Christian Andersen.

And what topped the Times

list? The Hobbit, of course. There was

just one book, Matilda, by Roald Dahl

(whom, I have to confess, I’ve always found wilfully zany, but I can see the

brilliance if not genius). Beatrix Potter gets just one entry: The Tale of Peter Rabbit; for sheer

terror, The Tale of Samuel Whiskers

(“ . . . make me a kitten dumpling roly-poly pudding for my dinner”) might have

been a better choice. No Edward Ardizzone? Shame.

Elsewhere on the list are the too-weird-for-my-taste Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster and The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken, which features wolves

in C19 Kent – come off it! The Silver

Sword by Ian Serrailler, the story of three children’s struggle for

survival in Nazi-occupied Europe, is by common consent a great book, as is the

closer-to-home story of survival Goodnight

Mister Tom by Michelle Magorian. But it’s a pity no room could be found for

the Morris Gleitzman books Once, Then and Now about a ten-year-old Jewish boy in occupied Poland.

But I’m now falling into the trap of picking “ought to be read” books.

Perhaps the best thing for adults/parents is to suggest titles gently, and for

them not to show disappointment if their own childhood favourites fail to find

favour. These kinds of lists always have as many supporters as opponents (on a

melancholy personal note, I couldn’t help noticing the number of books that had

passed me by as a child and parent and that I would probably now never read).

Among the correspondence it provoked was one letter that caught my eye:

“What

an ill-considered list. Top of the list? The cringe-making Hobbit, safe in his feebly imagined olde worlde 'Shire', surrounded

by Oxbridge dons – I mean 'wizards' – quaffing real ale and smoking pipes while

defeating those horrid proletarian Orcs. All the other usual suspects: the

creepy Maurice Sendak, loved by Freudian parents, loathed by children; The Wind in the Willows, only redeemed

by its illustrations; Roald Dahl, despite his being forced on children by film

and musical makers. Just check the falling sales and borrowing figures for

those books. Almost every title in the list is what an adult imagines a child

ought to read. No Jacqueline Wilson?”

Strong stuff. The letter-writer? Ralph Lloyd-Jones, a librarian from Nottingham.

He should know.

And, for what it’s worth, what did the TLS make of The Wind in the

Willows back in 1908? The review is worth quoting, as they say, in full:

August 2, 2013

July 31, 2013

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

“Why writers drink” is the subtitle of a new book by Olivia Laing, praised this week by Paul Quinn for its insights, care and close reading of texts. There is always the danger in such a subject of “reducing writers who drink to drinkers who write”. Laing avoids the traps by concentrating on hard drinkers, John Cheever, Raymond Carver and others, who both thought and wrote about their needs for alcohol. Suicidal and resentful fathers play a part in answering the “why” question. Carver’s famously commanding editor, Gordon Lish, is charged with putting the good of the stories above the health of their author. Laing concentrates on men because her mother’s lesbian partner was an alcoholic and she does not want to go “too close to home”.

Daniel Heller-Roazen considers the history of personal identity from Descartes to Hume, noting the difficulty of tracking the issue before the early modern age. Plutarch may have wondered at the Athenians of his time who referred to a local tourist attraction as the Ship of Theseus even though every timber of their ancient hero’s craft was changed every few decades. But ancient philosophers offered little on the identity over time of thinking subjects. Theologians came to see problems for divine judgment. Lawyers wondered whether a man was responsible for forgotten actions committed when drunk, an escape clause rarely available to Cheever.

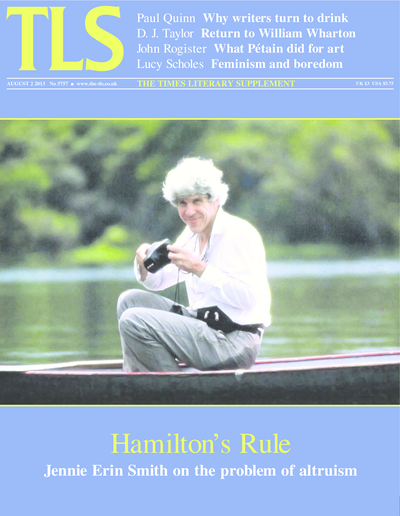

Charles Mosley is unimpressed by the efforts of Britain’s former Labour deputy leader, Roy Hattersley, to write about the Devonshires, one of Britain’s most enduring aristocratic families. His objections are not in the political oddity of the project. He notes merely an “embarrassingly slipshod family tree”, an ignorance of heraldry as well as history, and the misspelling of the Ottoman seat of government. The Sublime Port, he suggests, would be “a good brand name for a fortified wine”, the kind that writers drink when they are reduced to working on station platforms, the fate that, for a while, befell William D. Hamilton, the biologist, who is this week on our cover.

Peter Stothard

July 30, 2013

Waugh in Chagford

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

It’s raining here so, in an attempt to cheer myself up, it

seems a good moment to ask: is this the nicest open-air public pool in England?

The pool, which was opened in 1934, lies on the edge of the medieval stannary (i.e. tin-mining) town of

Chagford, in the heart of Dartmoor National Park. It is fed by the nearby river Teign.

The Times recently ran an item on “the 30 best lidos in

Britain” (we do love lists in this country, don’t we?), in which Chagford Pool

was placed a rather lowly 28th. I’d have put it much higher.

A mile or so down the road is Easton Court, the rather

unprepossessing hotel where Evelyn Waugh stayed, on army leave, in 1944, to

write Brideshead Revisited: “I came

to Chagford with the intention of starting on an ambitious novel”, he recorded

in his diary. Meanwhile, to his wife Laura, who was expecting, he wrote in

February, “The other guests in the hotel are all like old house-keepers. There

are plenty of eggs. I have found an old man who will go to Stinkers to get me

claret”, He was composing at quite a rate – “Mag. Op. steams along slowly at

about 1500 words a day”. The novel is signed off “Chagford, February-June,

1944.” To his friend and literary agent A. D. Peters he confessed “It would

have a small public at any time [he has the wartime paper shortages in mind]. I

should not think six Americans will understand it”.

On February 13, he notes in his diary “My wine arrived on

Thursday”. But the war is never far from his thoughts: aside from the anxiety

at the possibility of having his leave cut short – “No news from the War

Office” – he feels that “it is hard to be fighting against Rome. We bombed

Castel Gandolfo”.

The baby arrived in May: “Telephone message that Laura has

had a daughter and is well. A dull day’s work.” The next day, “. . . walked to

Mass at Gidleigh – delicious fresh morning and beautiful path by river” (“mass”

would of course have been pronounced with a long vowel).

Near Easton Court is the field where the Chagford Show is

held every August. In Chapter Four of the novel Waugh describes how Sebastian

and Charles are “sunbathing and watching through a telescope the Agricultural

Show which was in progress in the park below us. It was a modest two-day show serving the neighbouring parishes, and

surviving more as a fair than as a centre of serious competition”. It would be

nice to think that Waugh may have got the idea for the scene locally.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers