Peter Stothard's Blog, page 60

June 7, 2013

Alexandria: speech and Spectator

by Peter Stothard

Yesterday morning I sat in a recording studio (a sometime underground prison cell) to hear myself played, with flattering fluency, by Kenneth Cranham for the forthcoming version of Alexandria: The Last Nights of Cleopatra on BBC Radio Four Book of the Week. In the afternoon I emerged into the sunlight to read another account of myself, moving but surprising too, in this week's Spectator. When I wrote a three-week diary at the onset of the Arab Spring two-and-a-half years ago I never thought I would come out as so many different people.

The convention at the TLS is that the Editor's books are not reviewed in the paper. But this is the link to James McConnachie's Spectator piece.

June 5, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

Not far behind the pall-bearers at Margaret Thatcher’s funeral have come the publishers and writers. The military have now departed and the literary have taken their place, less colourfully and a little less obediently too. It would be wrong to say that books played a great part in the life of Britain’s first woman Prime Minister. While she enjoyed the company of supportive intellectuals in her Downing Street years, she also made clear, as Ferdinand Mount notes this week, that her ideas about her country were all formed when she was in her late teens. The current crop of assessments includes some decent works but will not be the end of the story-telling. Charles Moore has begun a “marvellous biography”, writes Mount, but his official chronicle has so far reached only as far as the Falklands War. The furthest rise and sharpest fall are yet to come.

While it would be impossible to write the history of post-war British politics without mentioning Margaret Thatcher, it would be perfectly possible, writes Matthew Sturgis, to do the same for art without a word on Rex Whistler. And yet the painter too had his own unique distinctions. The new study by Hugh and Mirabel Cecil creates a “rich and satisfying record” of a man who rose from modest beginnings, became a master of watercolour and drawing but painted much of his greatest work on theatre sets and little-seen walls. A man of rare talent and glamour, he died on his first day of war in Normandy in 1944.

In Commentary this week we publish Patrick Leigh Fermor’s account of a war incident which, as our contributor concedes, he had most certainly written and talked about many times before. But Adrian Bartlett’s version of the sinking of the Ayia Barbara in 1941 is taken from the full account that the author himself put down on paper for a local historian in Greek.

Tim Llewellyn reviews Andrew Finkel’s “lucid and informative” guide to Turkey, still a mysterious country to many and much needing lucidity at a time of sudden domestic protest and encroaching regional war.

Peter Stothard

Alexandria:The Last Nights of Cleopatra (2)

by Peter Stothard

I am learning how to talk

about Alexandria: The Last Nights of Cleopatra (published later this

week: available from all good bookshops etc).

'Why did I write it?' has been

the FAQ of FAQs at festivals so far, from Fowey to Hay-on-Wye. No surprise

in that but it has not been so easy a question to answer.

Ice-bound London airports in New Year

2011 played a part. So, more importantly, did unexpected conversations

with my oldest friend as he was about to die. There was the coincidence that I

was in Alexandria in the weeks before the beginning of the Arab Spring. And

then the increasingly awkward memory that I had many times begun a book about

Cleopatra and failed to finish it.

This is a book that connects old friends, new

acquaintances, men and women from the distant past, the near past and

now. 'Evocative, touching and funny in the finest tradition of English

letters': those were some appreciative words at the weekend from the

Egyptian novelist and critic, Ahdaf Soueif.

She characterised Alexandria as

'a love letter to (a very particular) England and a rumination on the

nature of history and politics'. Cleopatra’s story, she said,

'provides the fixed point in the past, his story with Cleopatra the fixed

point in the present'. I won't disagree with that.

Like On the Spartacus Road

in 2010, Alexandria is a diary, a daily record of

three weeks seeing some unusual things and confronting much about myself that I

had previously avoided. And this is the result - now published very beautifully

by Granta and about to be read as BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week from June 17. I

can still feel surprised - and am still learning to talk about it.

Oscar Wilde's sac de voyage

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Have you ever wondered what The

Importance of Being Earnest reads like in French? No, neither have I.

But to anyone who would like to find out, I can recommend Charles Dantzig’s

new translation, in a nicely presented bilingual edition published by Grasset. The title itself is a telling choice for a French version:L’Importance d’être constant plays on

the not very common name Constant. Jean Anouilh, by contrast, called his version, in 1954, Il est Important d’être aimé.

Charles Dantzig is indefatigable: by my calculation that is his third

publication in a matter of months. (His À

propos des chefs-d’oeuvre will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.) Maybe he’s in too much of a hurry:

in his preface he refers to The Portrait of

Dorian Gray – a common enough error, perhaps.

According to his biographer Richard Ellmann, Wilde considered applying

for French citizenship: “If the Censor refuses Salome, I shall leave England to settle in France where I shall

take out letters of naturalization”. Elsewhere Wilde proclaims, “There is a great deal

of hypocrisy in England which you in France very justly find fault with”. But in

spite of these sentiments, Wilde's work seems to have been a little neglected in France, its author held up, in Dantzig’s

phrase as an “amuseur de petites bourgeoises sentimentales”. Un Mari idéal was only first staged, successfully, in Paris in

1994. And I see there’s a production of The Importance of Being Earnest – again, in a different translation – scheduled for this year’s Avignon Festival.

Dantzig’s introduction has some good nuggets: a musical comedy entitled

Oscar Wilde opened in the West End in 2004 and closed after one night. It was

described by one newspaper as “the worst musical in the world, ever”. He has

rather camply titled his introduction “La Première Gay Pride"; in it, he breezily

runs through the well-known story of Wilde’s triumph and downfall.

But Dantzig

claims to have unearthed some new information, "not told in any account of

Wilde’s life up till now, not even the excellent Richard Ellmann”, whose

account of the funeral in Bagneux, some 7 km south of Paris (his remains were

transferred to the Jacob Epstein tomb in the Père Lachaise cemetery in 1909)

includes this: “At the graveside there was an unpleasant scene, which none of

the principals ever described – perhaps some jockeying for the role of

principal mourner. When the coffin was lowered, [Lord Alfred] Douglas almost

fell into the grave” (Oscar Wilde,

1987).

We learn from Dantzig that the poet Paul Fort (1872–1960), the author of Ballades françaises, gave a

description of the funeral on French radio in 1950. But, as relayed by Dantzig,

Fort’s account doesn’t appear to add much. Ellmann mentions a “Marcel

Bataillant” as having attended. Fort refers to Marcel Batilliat, “petit

romancier charmant venu spécialement de

Versailles” (not that far away). Batilliat was apparently a friend of Émile

Zola (although he doesn’t feature in the index of Frederick Brown’s mammoth

biography).

The TLS had a paragraph

on one of Batilliat’s novels, La Liberté (1913), that goes: “There are three heroines in this story, and all three wish to lead their own lives. One seeks liberty through a loveless marriage; another in a brief liaison; and the third in a series of lovers. One can imagine such a book

being humorous, but, like so many French novels of the kind, the author has

written it with a purpose – this being, it is hardly necessary to say, to show

that true liberty is found in normal, sane surroundings”. You had to be

there.

Oh, and the line everyone knows from the play: "Un sac de voyage?"

June 4, 2013

Sky-high at the RA Summer Exhibition

by ANNA VAUX

The

four piece steel band playing at the top of the stairs at the Royal

Academy on Monday was presumably there to make us feel summer had

arrived. And as luck would have it, it had. I thought the President of

the RA looked relieved as well as warm when he announced to a crowd

sweltering under the glass roof of the large main room that the sun

always shines for the Royal Academy summer show.

This was Varnishing Day – or, more accurately, non-members

varnishing day, when the selected artists and their guests get to see

the show before it’s open to the public – so-called because in the days

when you varnished the oil on your painting, this was the day on which

you could go in to the academy and finish off. Turner used to put a drop

of red paint in his varnish to make his pictures glow and to make those

of his neighbours look flat and lacklustre.

I

wondered out loud if this sort of thing still went on, if there was a

modern day equivalent to varnish tampering, painterly doping. You have

to watch the hangers, my RA friend told me, helping himself to a handful

of mini cheese scones from a passing tray. I don’t trust the hangers.

They can sky you.

RAs

are supposed to be hung at eye level. This is important in a show where

there is such a huge amount to look at. The President told us that

11,000 works had been submitted to this year’s show – and there are 1270

listed in the Summer Exhibition booklet. It’s hard to know where to

turn, what to give attention to, even which direction to go when you

arrive. I turned right, which is wrong, and came through the show

backwards, looking for something to settle on, some way in to the

exhibition.

My

moment came in the Sculpture Room, which was airier and cooler than the

others, with large works surrounded by lots of space, where I saw what

must be a piece by Michael Landy: a red worker’s stepladder in the

middle of the floor. Part of the fun of the summer show is guessing

which works are by which artists, since the works on the walls are

identified only by a number and you have to then source the number in

the booklet. Michael Landy had a bin in last year’s show

and I watched several people try to put rubbish in it. I noticed a small

black m on one of the steps of the ladder, and an e,

placed at an angle, as though it had slipped slightly. A Duchampian

clue, I thought, though while I was looking for the number with which to

identify it, a man in overalls came and wheeled it away.

I

turned my attention to people watching – another fun part of the

spectacle, surely. You can tell an RA by the huge gold medallions they

wear on looped gold chains round their necks, like lord mayors, or

pearly kings and queens. But Varnishing Day is the wrong day for people

watching, it turns out. My RA friend, who had taken his medallion off,

perhaps because it clashed with his braces, said people watching was

tomorrow. I asked if that day had a special title. He couldn’t remember

exactly. It’s the Glamorous Day, he assured me, brushing crumbs of

meringue from his front and glugging back a large glass of Pimms.

After

that, the fun is to look for the most expensive works of art – Zaha

Hadid’s, perhaps (£450,000), or Gary Hume’s (£168,000). Looking for

the cheapest pictures is not the same sort of fun – though flicking

through the catalogue I saw plenty of work that seemed reasonably

priced, provided I suppose, that you like it, or think it’s any good.

And

is any of it any good? When Picasso showed at the Salon in Paris, he

was asked how he thought his work looked. He said, it looks terrible,

like everybody else’s, but the difference is I know why it looks

terrible and they don’t. My RA friend told me that story, nodding

towards the main room, filled with hundreds of works of art, all bathed

in that famous natural sunlight. A steaming pile of horseshit, he said

loudly. I assume he was talking about his own picture, which I now saw

had been hung rather high up. Skyed, in fact.

June 3, 2013

A weekend at Hay

By TOBY LICHTIG

The sun came out for

the final weekend of this year's Hay Festival, the surrounding hillsides, well

nourished by recent downpours, almost impossibly lush amid the dazzle.

Fertile as ever was the programme, the recent spat over apparent snubs and

prejudices looking increasingly like a breeze in a Fleet Street

teacup. The marquees were full, the deckchairs out, the punters looked

delighted.

Navigating the packed programme is always a challenge. Our first stop on Friday evening was to

see the TLS Classics editor Mary Beard, who spoke about her recently published

collection of reviews and essays, Confronting the Classics, and the

significance of the verb in the book's title (“there's no point in being deferential

and reverent”).

This was probably the

noisiest audience of the weekend, and Beard received a rapturous reception, not

least when one member stood up to thank her for her services to feminism and

recent attack on internet trolling. Returning to the main subject, Beard spoke about why Classics is still “relevant” (it's “so embedded in

Western culture that you cannot remove it without leaving a bleeding

torso”), while reminding us that this state of affairs is also a matter of happenstance: “Dante

didn't read Gilgamesh; he read Virgil . . . . But if the

Persians had won the Persian war we'd be in a different place.” Speaking

about her recent television series, Meet the Romans, Beard artfully let slip

that she's working on another television project, about Caligula. “No one is

to tweet this”, she cautioned, as 1,000 mobile phones pinged into life.

On Saturday morning,

Simon Hoggart gave a wonderfully commanding performance about the past thirty

years of parliamentary life. Part lecture, part stand up comedy, his routine focused largely on the sanity of Margaret Thatcher, a subject about

which Hoggart appeared to be in little doubt: “She was completely and

utterly bonkers”. The sketch writer then trotted out a few – it must be

said – rather hackneyed anecdotes about the former Prime Minister's sense of

humour, including the story about how a line from Monty Python's “dead

parrot” routine ended up in one of her speeches in which she poked fun at the Liberal Democrat "bird of liberty" logo. Failing to get the joke

about the symbol – “this is an ex-parrot” – Thatcher was first shown the sketch by her writers. She is said to have remained “absolutely

stony faced”, later asking, “This Monty Python. Are you sure he's one

of us?”

Similarly commanding

and entertaining – though rather more serious in terms of content – was Jay

Rayner, who delivered a performance lecture, complete with graphs, graphics and

a conversation with himself, about the current state of the global food

industry. Rayner's basic thesis, explored at greater length in his recent book,

A Greedy Man in a Hungry World (to be reviewed in a future edition of the TLS),

is that the current vogue for locally sourced produce, organic fare and farmer's markets is little more than a middle-class fad which

will do nothing to solve the encroaching food crisis. Rayner argued persuasively that food miles account for a

tiny proportion of a product's carbon footprint and reminded us that we've been

genetically modifying what we eat for centuries. "We're supposed to favour the

artisanal over the industrial", he said; but what we actually need to do is produce

more, grow and distribute it more efficiently, and cut down on land-intensive

food such as beef, rather than simply buying nicely-packaged versions of the

stuff. Rayner argued for "sustainable intensification" and a

necessary hike in some food prices, to stop farmers allowing their fields to

lie fallow (one particularly tragic case involved a recent British plum harvest

left to rot after farmers were undercut by imports). "Unless we pay more

for our food now, we'll have to pay vastly more later", said Rayner.

Food was also on the

mind of the journalist and China commentator Jonathan Fenby, who spoke about

the "certainty" of a food crisis in China, after the false economy of several years of

good harvests. In a deeply absorbing session, Fenby confronted numerous other

problems facing the country, including those caused by its growing,

disenfranchised migrant worker population, its political corruption, creaking

judiciary, an unaccountable "shadow" banking system, and a set of

vast and essentially "frozen" dollar reserves. These factors – and

more – contribute to Fenby's belief that China is unlikely to

"dominate" the twenty-first century.

Today's literary

climate demands that successful authors must also be captivating speakers. This does

not, inevitably, suit everyone. The highlights of the weekend were notable for their

oratorical excellence and feats of presentation; other events fell rather more

flat. Peter Sawyer, whose The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England is reviewed in this

week's TLS, while charming and full of insight, didn’t quite make the

distinction between an academic lecture and a literary event; a talk about

teenage runaways was filled with poignant and memorable stories but otherwise

lacked substance; Rose Tremain and John Mullan made an excellent double act –

both witty and confident speakers – but their discussion of historical fiction

could have benefitted from greater literary context. Some interviewers were more inventive in their interrogations than others. Audience questions were generally apposite. The food was

varied, excellent and expensive. The bookshop was selling out. Hay, whatever

the recent imbroglio, appears to be in rude health.

May 30, 2013

In the best possible taste

By TOBY LICHTIG

The subject of artistic taste has always been fraught, bound up as it is with notions of intellectual elitism, class

politics, social identity and consumer power. Taste is both a tool for

organizing society and a matter of individual freedom.

Writing about the subject in The Spectator in 1712, Joseph Addison defined “taste” as “that

Faculty of the Soul, which discerns the Beauties of an Author with Pleasure,

and the Imperfections with Dislike”. Our artistic preferences, for Addison,

were imbued with divine powers – or potentially devilish ones.

Literary taste is perhaps more fraught than most

because literature is such a democratic artform: cheap to produce (even before

the digital revolution), available to the many (at least since the printing

press), and a temptation to anyone interested in a good story. Literary

taste has meant different things in different times, though what we value about

literature has perhaps remained more static. As Arnold Bennett wrote in another well-known essay on the subject, “Literary Taste: And how to form it”:

“The aim of literature is not to amuse the hours of

leisure; it is to awake oneself, it is to be alive, . . . . It is well to

remind ourselves that literature is first and last a means of life, and that

the enterprise of forming one’s literary taste is an enterprise of learning how

best to use this means of life.”

The question of literary taste and the current state

of “literary values” are the subject of a panel debate I’ll be taking part in

on Friday, June 7, somewhat ominously entitled “Pandora’s Box”. The discussion – hosted by

The Literary Consultancy, an organization that has made a business out of

evaluating literature – is being held at the Free Word Centre in Farringdon, as part of a two-day conference on Writing in the Digital Age, in partnership with the TLS.

Also on the panel will be Andrew Franklin, the founder

and Managing Director of the excellent Profile Books; Scott Pack, the publisher

of the experimental HarperCollins imprint The Friday Project and the director

of another experimental (community) literary project called authonomy; the

“book doctor” Sally O-J; and The Literary Consultancy’s co-founder Rebecca

Swift.

The focus of the debate will be on the brave

not-so-new world of the digital. We will consider how literary

values have been either eroded or enhanced by social media, Amazon, citizen

journalism and the literary blogosphere. We will question whether

the gateways to literature – from academia to publishing in all its forms, from

creative writing courses to literary agents, professional journalism to Twitter,

casual book groups to word of mouth – have changed the quality and quantity of

what is available and the ways in which we think about and critique it. We will

grapple with the consequences of print-on-demand and self-publishing, the

demise of the high street bookshop, squeezed margins at traditional publishers

and the inexorable – and potentially redemptive – rise of the e-reader.

Is the question of literary taste now more fraught

than ever? Certainly people are worried: about corruption and self-promotion in

Amazon online reviews; the dreary ubiquity of prize culture and its

concomitant, list culture; the lack of professionalism in the vast amount of

online criticism; the demise of the literary editor and remunerated hack; the

sheer amount of literary material being produced and written about, sifted through or allowed to

proliferate in an advanced state of bookish metastasis. Who, we might ask, are the "gatekeepers" now?

Last year, our Editor, Peter Stothard, provoked howls

of consternation and hollers of support in equal measure by daring to suggest,

in an interview in the Independent,

that “not everyone’s opinion is worth the same”. “Criticism needs confidence in

the face of extraordinary external competition”, Peter said. “It is wonderful

that there are so many blogs and websites devoted to books, but to be a critic

is to be importantly different than those sharing their own taste.”

Peter was right, of course, and somewhat

unsurprisingly I intend to make the case for professional criticism as one of

the cornerstones of a healthy literary climate. Literary journalism is a means

of stepping back from the babble, assessing what is out there, remembering to

be sceptical.

For me, a decent literary review serves two chief

functions: it should critique the book in question, impartially, preferably

against a broad backdrop of the reviewer’s learning, interests, frame of cultural

reference and painstakingly assembled prejudices; and it should perform a

discrete function as a stimulating and diverting piece of writing. Or, to put

it another way, a review has to serve both the author of the book and the

reader of the review. That good criticism is enjoyable is, I believe, why

there will always be people prepared to pay for it – and professionals prepared

to devote their time to it.

But professional criticism (a niche genre even in its

heyday) is just one component alongside all the other modes and means of

talking about literature. And even as we worry about being engulfed in a sea of

unmediated literary outpourings, I see new filters popping up all around: innovative

publishing projects, high quality blogs, the vast flowering of literary

festivals, new little magazines, in digital and print, which rise and fall and

rise again, much as they've always done.

It's worth bearing in mind that we've been worrying

about literary "values" ever since we first had literature. Indeed, just

two decades after Addison’s essay, the Weekly Register was decrying “the degeneracy of Taste since Mr

Addison’s time”. And as for Bennett: “The one primary essential to

literary taste", he wrote, "is a hot interest in literature”.

But what are your thoughts? Is being passionate enough? Are standards declining or blossoming? Is there such thing as too much literature? Who are today's gatekeepers? And are they doing a good enough job?

May 29, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

Why do we still study the Roman empire? Because it was so successful. Why was it so successful? The Romans themselves asked that question and, like the rest of us who came later, could not find a single satisfactory answer. As Mary Beard discusses this week, one of the first attempts to explain the superpower to itself came from a Greek called Polybius, tutor to the young Scipio Aemilianus, conqueror of Carthage and scion of other great Roman conquerors. Although it is not easy to decide how successful Polybius was himself (only five of his forty books survive complete), he left behind numerous citations by other historians, an oeuvre that in the twentieth century so dominated the life of the classicist F. W. Walbank that “it is now almost impossible to think of Polybius separately from Walbank, or vice versa”. Beard notes the personal cost as well as the historical gain in this relationship, a subject not often confronted in festschrifts and one that should be “required reading for every academic”.

Eventually the city of Rome was supplanted by Constantinople. Peter Frankopan reconsiders the deceptive simplicities of this shift. T. Corey Brennan praises Caroline Vout’s dazzling account of how Rome so long saw itself as a city of seven hills. For students of both Greece and Rome, the sacrifice of animals is one of the customs deemed to define the ancient against the modern. But why did it begin? As a relic of Palaeolithic humans hunting wild beasts? A reminder of communal dinners once men and women had settled down on farms? The formal point of sacrifice was to communicate with the gods but, when Peter Thonemann assesses the origins, he finds the best explanation in “an act of violent killing in order to eat”.

The latest novel by the eighty-seven-year-old American novelist James Salter begins in 1945 at the end of the Pacific War: but its massive naval clashes evoke the violent rituals of the Iliad, writes Michael Saler. Salter’s life and fiction demonstrate “the conjugation of two sets of ideals – that of archaic moral values and complex aesthetic truth”.

Peter Stothard

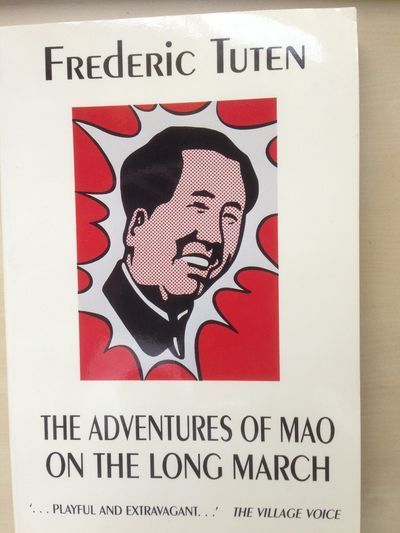

Roy Lichtenstein and Frederic Tuten

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Anyone who visited the recent wonderful Roy Lichtenstein retrospective

at Tate Modern and made use of the audioguide will have heard a tribute to the

artist from his friend Frederic Tuten: “I knew him for more than thirty years.

I think he was the happiest person I’ve ever known in my life, ever. Ever . . .

. It was really remarkable to know him”. Elsewhere he wrote “To understate,

that is the quiet beauty of the work”.

Tuten, a novelist and writer on art, has had considerable succès

d’estime with his five novels (he was born in 1936 in New York). Lichtenstein

put the seal on the friendship by providing cover illustrations for two of

Tuten’s published works, both “created expressly for this novel”: The Adventures of Mao on the Long March

(1971) and Tintin in the New World

(1993).

Any self-respecting Tintinophile will be familiar with Tintin in the New World, a playful and

imaginative expansion of the boy reporter’s life experience: he loses his

virginity and receives instruction from the main characters in Thomas Mann’s cerebral

door-stopper The Magic Mountain. He

grows a beard and gets a sun tan! The novel is dedicated to “the memory of

my friend Georges Remi (Hergé)”. Susan Sontag, whose approbations can be found

on the covers of more than one of Tuten's novels, wrote

of it “I love the way the novel deepens as it goes, the music, the sadness, and

the inventive humor. Its wisdom and its art moved me very much”. Of the Mao

novel she said “. . . Tuten has written a violently hilarious book”, while another

novel, Tallien: A brief romance

(1988), prompted the comment “There’s nothing like the ride and rush that

Frederic Tuten can give. His ‘brief romance’ is the real thing: unforgettable” -

not a bad trio of recommendations from such an eminent critic. (Mao also drew what must surely have been

a rare puff from Iris Murdoch: “Delightful and original - funny and bitter and

serious”.)

I read The Adventures of Mao recently and don’t feel it’s ageing well; its

experimentalism is a little willed. Tuten is not uncynical: at one point he has

a footnote that reads “See last month’s column, “Money to be made in

meditation”. Later, without warning, he indulges in a parody of Bernard

Malamud. I only know because Tuten tells the reader in his “Sources” at the

back of the book. There are also too-easy parodies of Kerouac and Hemingway, that are

wholly unrelated to the narrative. Lichtenstein’s portrait of Mao is nicely

ambivalent in its expression. I wonder what he made of the book.

Tallien, an imaginative reconstruction

of the life of the French revolutionary Jean-Lambert Tallien (1767–1820), who falls in love with and rescues a

beautiful aristocrat from the guillotine, is the most satisfying of Tuten’s

novels; it has its quirky moments too: a courtroom is described as smelling “like

the disinfected Métro stations of East Berlin”.

The Lichtenstein exhibition was reviewed in the TLS by James Hall, who didn’t appear very taken with it. I loved its wit

and sense of fun, the way it lifted the spirits, as well as the sexiness of the Late Nudes (“soft-porn cinematic cliché”,

according to Hall). In his excellent booklet Roy Lichtenstein: How modern art was saved by Donald Duck, Alastair

Sooke points out that “everything was fair game as a potential source for art.

In fact, the more clichéd something was, the better. You could even say that

Lichtenstein was the most clichéd artist who ever lived. But it was the way

that he presented clichés that made him great”. Sooke also fronted a BBC

documentary about the artist before the show in which he interviewed

Lichtenstein’s still-beautiful widow Dorothy.

One thing particularly struck me

about the show: the number of works borrowed from private collections (who

wouldn’t want a Lichtenstein hanging on their wall?), but having said that, one of my

favourites, the still life “Purist Painting with Bottles” (1975), was on loan

from the Wolverhampton Art Gallery.That I would dearly love to have on my wall.

May 24, 2013

“Blog”: the ugliest word I ever heard

By Thea Lenarduzzi

“BLOG is the ugliest word I ever heard . . . ”. It pains me somewhat to write this post in the wake of these lines read by Anne Stevenson last night at the final event of British Academy Literature Week.

Stevenson read a selection of her poems (some from her most recent – “probably my last” – collection, Astonishment), in such a way as to leave us in no doubt that, despite her age (she is celebrating her eightieth year) and partial deafness, the commitment to music evinced by her youthful piano and cello playing has not waned in the slightest.

We heard poems about wonder (or “astonishment”, as Stevenson insists all her poems have been) drawn from the many phases of her life and career: from an early metaphysical exercise, “Sierra Nevada”, in which the blow of nature’s indifference is softened by the suggestion of reconciliation in rhyme (If we were to stay here for a long time, lie here / like wood on these waterless beaches, / we would forget our names, would remember that / what we first wanted / had something to do with stones”), to her more recent poems written for family weddings and friends’ birthdays.

“Small Philosophical Poem”, written in the 1980s, conjures a strange domestic scene, playing on Stevenson’s upbringing by a philosopher father (who studied under I. A. Richards and Wittgenstein) and novelist mother: it’s dinnertime and Dr Animus, “whose philosophy is a table”, is “eating his un- / exceptional propositions”, when “his wise / wife Anima, sweeping a haze-gold decanter / from a metaphysical salver, / pours him a small glass of doubt . . .”.

After such breadth and variety, Stephen Regan’s discussion on (ode to?) anthologies was a welcome trot through the “Where have we been?” of modern British poetry, bringing us smoothly to the second phase of the evening – a panel talk asking, “Where is British Poetry Today?”, for which Regan and Stevenson were joined by Simon Armitage.

Taking in Al Alvarez’s survey of the state of modern poetry (The New Poetry, 1962), Blake Morrison and Andrew Motion’s 1982 Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry (with its uncomfortable inclusion of Seamus Heaney, which occasioned the lines, “Be advised, my passport’s green / No glass of ours was ever raised to the Queen”), and Armitage and Robert Crawford’s corrective (though admittedly awkwardly-titled) Penguin Book of Poetry from Britain and Ireland since 1945 (1998), Regan suggested a few directions, “should the editors of the next anthology come knocking”: more existential dilemmas, more eschatology, and more space for mourning, grief and loss. (Thankfully, however, humour too would play a part, along with poems about nature – motivated by contemporary ecological concerns, or more general explorations of place – and heritage, too.)

But the thing with anthologies is, no sooner is their poetry of the “now” than it is of the “then” (to paraphrase a line from Stevenson): tidied, bound and shelved. The names are ones we know and have known for some time (Larkin, Hughes, Muldoon, Oswald and Stevenson herself), which attest to the fertility of pastures old(er). Armitage’s reassurance that “there’s never been a golden age of poetry” was well-timed. We must think in terms of moments, not eras, he said, for poetry is where it has always been – “just about alive . . . . Utterly unkillable”. There is now no dominant style, no school to speak of; poetry prizes dictate the “industry standard”, but little more. The future of poetry is tied up with that of the book and print media in general; “the book in the hand”, as Regan later termed it – “the book object”, Fiona Sampson, chairing the panel, volunteered (“I’ve never thought of a ‘book object’”, said Stevenson) – is threatened by a sea of “poetic space junk”.

And yet Armitage was cautiously unpessimistic (“concerned”, yes, but not “worried”, as such…). He noted in the work of his students at the University of Sheffield the development of an “amphibious” quality, which makes their poetry equally at home on the page, the screen, stage or film. Should we take this weakening of written words to be an opportunity for a strengthening of those spoken, shouted or sung? Is this, perhaps, evidence of poetry reinventing, or, rather, rediscovering itself?

More overtly underwhelmed by the possibilities of mixed media was Stevenson. “There’s an awful lot of poetry about”, she said, emphasizing one word in particular. “And with 9,000 teachers of Creative Writing in US Colleges, turning out ten protégés each . . . you’re bound to bring the standard down”. With characteristically wry humour she questioned that age-old obsession with “doing something ‘new’” (“it’s terribly hard to do anything new, you know”), which operates at the expense of more self-probing verse (not to be confused with the “Words about words about words to pamper the ego / Of some theoretical bore”); and “Do It Yourself Poetry” built in ignorance of proper craftsmanship (with no sense of rhythm, form, heritage ). “We are losing contact with language . . . . I wouldn’t even begin to talk about the visual arts, ‘Conceptual Art…’” (that carefully placed emphasis again, a glint in her eye, and a laugh: “I am eighty, you know!”).

“I’ll just throw all of that in”, Stevenson quipped before bringing the evening to a close with a reading of her most recent poem, “An Old Poet’s View from the Departure Platform”, its final stanza running thus:

“I gaze over miles and miles of cut up prose, / Uncomfortable troubles, sad lives. / They smother in sand the fire that is one with the rose. / The seed, not the flower survives.”

And there we all were, ready to go.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers