Peter Stothard's Blog, page 57

July 29, 2013

Economy of Thought

by TOBY LICHTIG

A crowd of protestors marches through the streets,

united in their stand against capitalism. Six floors above, a banker waves a

£50 note outside an office window. Having attracted the attention of the

demonstrators, he lets go of the money and watches it waft down to the pavement.

The man has made a bet with his colleagues.

The agitators, he says, will be unable to resist it. Their idealism is flimsy:

once the chance for easy cash is put before them, they'll fight tooth and claw.

But the man is wrong. Instead, a protestor

sets fire to the note. Falsely sensing trouble, the police intervene, violently,

and the protestor is smashed on the head, leaving him unconscious and in hospital.

This incident – inspired by a true story – is

the basis for Patrick McFadden's agile and intelligent play about corporate

greed, careerism and personal responsibility. The narrative follows the fall-out

of the episode as it develops into a scandal, and the bankers are threatened

with exposure.

The question of complicity is complex. It

was Reece (Jonny McPherson) who dropped the note, but the others egged him on.

Amanda (Katharine Davenport) wasn't even at the window – should she be

implicated too? The debacle is further complicated by Amanda's sister and

flatmate Collette (Rose O'Loughlin), a journalist on the look-out for a story.

Motivated more by the greasy pole than the moral maze, she presses her sibling

for information. This could be her break; it could also be Amanda's downfall.

Hypocrisy abounds. Reece may be odious, but

at least he is honest. His colleagues roll their eyes at him but are they any

better? Any sweetness in Tom (Ed Brody) seems predicated on his juniority. Amanda's ideals are subservient to the business of rising through the ranks. As for senior

management, they are horrified: not by the event but the negative publicity.

With a running time of just over an hour, Economy of Thought is aptly named: McFadden packs a great deal of cerebral material into a surprisingly short time. It is

witty, punchy and unfolds at a pleasing pace. Many productions are twice as long and

half as good.

Friday's performance at The Yard in Hackney

Wick was a preview for the Edinburgh Festival, where it is set to run for most

of August. If you're in town and have some spare time, I'd highly recommend

it.

July 24, 2013

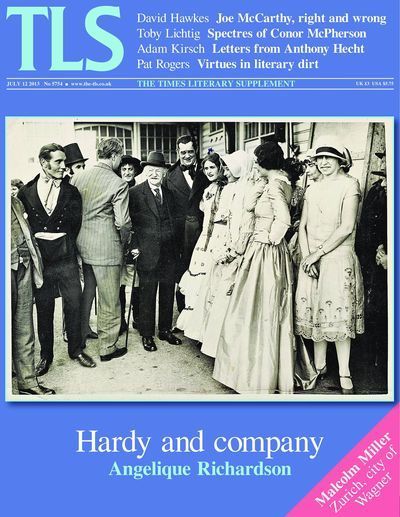

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor on the TLS sports issue

This is the sports issue of the TLS and regular readers may be

reasonably disquieted at the prospect of descent into running, jumping,

kicking, throwing and other pursuits deemed in one way or another to be

sporting.

Never fear. We begin with mountaineering and the “multiple modernities” which

Peter H. Hansen sees in the acts of those claiming to see and climb

mountains for the first time. The first man to “discover” Mont Blanc was an

Englishman who visited Savoy’s glaciers in 1741 and published a pictorial

pamphlet. Next we turn to cricket, a peak of human endeavour which the

English can more easily claim to have discovered although, as Stephen Fay

notes, the Indians like to see it first within the most ancient paths of

their own Hindu culture. Indians certainly own the game now, he concludes,

reviewing two books on high-speed matches, gambling, corruption and the only

place where the passions of rich and poor ever meet.

Football will be back in Britain soon and the TV screens are already aflicker

with the prices of Croatians and Brazilians trafficked between London, Paris

and Rome. Toby Lichtig considers Red or Dead, a novel by the

“unflinching” David Peace about how Liverpool Football Club rose from lowly

“second division” origins to become “one of the greatest teams of the past

half century”. Its central character is a manager who once said that

football was “more important” than life or death. Lichtig finds little to be

said in support of Peace’s “cut-and-paste prose” and much that is

appropriately predictable.

Who was the first to have a Jockey Club? If Maryland had one in 1743, “why did

it take at least another seven years before the founding of a British one?”

Donald W. Nichol poses the sporting question and discovers the reassuring

answer that the institution which set the rules for horse racing has an

English history stretching further back than once was thought. In the 1720s,

and maybe as early as 1709, “the Jockey Club” was already doing what it does

best, providing a home for a man who has “gambled away his trousers”.

Peter Stothard

July 19, 2013

Baseball or cricket? It's a no-brainer

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“Gerald died that afternoon. He was broken up in the

football match.” This anecdote appears in E. M. Forster’s novel The Longest Journey, and has always

struck me as oddly phrased: “broken up?” And how exactly did he die as a result

of an injury during a school football match? We’re not told. It happens early

on in the novel, so poor Gerald doesn’t have much impact on the story.

It occurs to me that organized team sports play

really quite a small part in C20 English fiction. For example, if you exclude

P. G. Wodehouse it’s striking how infrequently cricket appears in post-WW2

novels (or maybe I’ve just been reading the wrong ones). Looking at the

“cricket in fiction” section of a certain website confirmed that there are

indeed slim pickings.

This is not an original observation: it’s often been

pointed out that a game that has over the decades attracted so many good

writers lacks its great novel. Yet it’s a game made for a set piece at least – a Test

match, or even a village game would do. Yes, there is L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between, memorably filmed by

Joseph Losey with that great scene involving the rustic lover Ted Burgess

played by Alan Bates smiting a six off the bowling of the aristo cuckold

Trimingham (Edward Fox).

Joseph O’Neill’s acclaimed novel Netherland has sat on my shelf unread

for some time now. Opening it the other day I came across the following (the

novel is partly about a cricket team . .

. in New York): “Softball, my teammates and I observed with a touch of

snobbery, was a pastime that seemingly turned on hitting full tosses – the

easiest balls a cricket batsman will ever receive – and taking soft,

glove-assisted catches involving little of the skill and none of the nerve needed to

catch the cricket ball’s red rock with bare hands.”

You could extend that definition to baseball – I’m

sure that’s the implication. (And what about baseball’s role in American

fiction? There’s Chad Harbach’s The Art

of Fielding and the opening of Don DeLillo’s door-stopper Underworld, which I haven’t read . . .

and many others no doubt – although, looking again at Richard Ford’s fine The Sportswriter, I

couldn’t spot any refs to baseball in that novel.)

Which brings me to a direct and totally unnecessary

comparison between the two sports: one is played professionally in a World

Series, that world stretching from the East Coast to the Pacific and the

Canadian border to Mexico. The other stages a World Cup every four years, featuring

16 teams. It’s not a “world” cup in any real sense, but there are plenty of

associate members of the International Cricket Council, including the rapidly

improving Afghanistan, Kenya, Canada and . . . the United States.

What about the game itself? In one, the pitcher

generally hurls the ball at the batter; it doesn’t bounce. The batter tries to

whack it out of the park and if he makes contact, drops the bat and runs to

first base, or, if he gets lucky, makes a home run. The fielders wear mitts in

order to facilitate the catching of the ball. It strikes me as being not much more than glorified

rounders (a game I played in the park last Sunday).

Cricket’s equivalent of the pitcher, the bowler,

comes in many guises: fast, medium-fast, swinging, seaming, leg-spinning,

off-spinning. The ball almost always bounces of course, and deviates off the pitch: the

batsman therefore can’t just whack it, but has a range of strokes, defensive

and attacking, at his disposal. Of those in the field, only the wicketkeeper

wears gloves. Add to that the influence of the weather conditions. And then there’s the fascination of the statistics: batting and

bowling averages, immortalized in the game’s annual, Wisden.

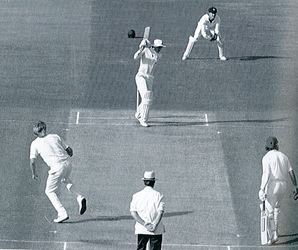

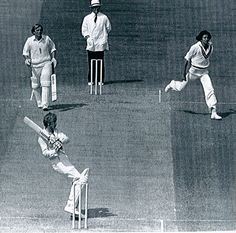

I would rather watch somebody like David Gower stroking the ball effortlessly to the boundary (below, twice) –

than some guy trying to slam it out of the park.

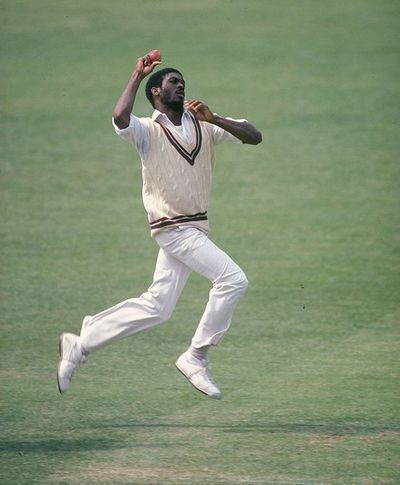

And when it comes to poise and athleticism in bowling, what about the great Michael Holding in full flow (below)?

I'm sure this guy's a great pitcher, but it just doesn't do it for me:

The complexity and sophistication of cricket means that it simply has no peers. And as the current Test series between England and Australia shows, it can be pulsating over a full five days.

As for golf – a good walk spoiled as Mark Twain said – don't get me started.

July 17, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from Editor

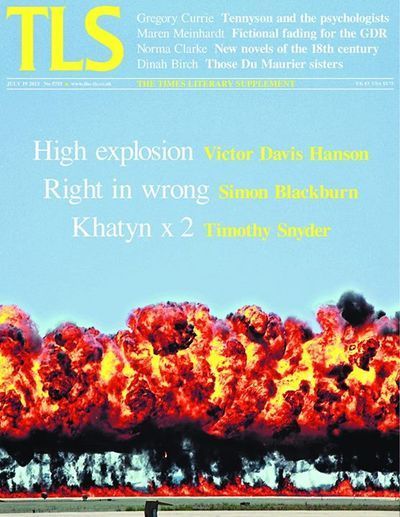

The military historian, classicist and raisin farmer Victor Davis Hanson recalls “the most lethal single day in the history of human conflict” when his father joined the napalm-fed B-29 bomber raids on Tokyo, March 9, 1945.

The bomber commander, Curtis LeMay, “acknowledged that he would have been tried for war crimes” if America had lost that war. But napalm, Hanson says, has become an unhelpfully persistent “metaphor of destructive American excess”, not so much because of the Tokyo attacks as its later use in Vietnam. Reviewing a “biography” of the diabolical goo, and a history of saltpetre, the main ingredient of explosives before the discovery of cordite, he doubts whether the chemistry set has contributed as much to the thinking behind warfare as critics allege. His father and his fellow pilots could at least, however, smell the results of what they were doing, unlike the subjects of Christopher Coker’s book, Warrior Geeks, who fight from computer terminals and armchairs far away from their enemy.

Gregory Currie considers the relationship between Victorian poetry and the nineteenth-century advance of psychology, chiefly through the works of Tennyson, analysed in Gregory Tate’s book The Poet’s Mind.

Currie approaches the arguments cautiously, noting “valuable interactions” between poetry and the new science but remaining sceptical about any similarities between poems and experiments. In Commentary this week three scholars combine to assess audience responses to Antigone and King Lear using the measuring sticks of science – with “one strikingly unexpected result”.

It has become a commonplace of criticism that “well-written sex scenes” are increasingly rare in the contemporary novel. Norma Clarke has been reading four tales of eighteenth-century life and gives a special welcome to Jonathan Grimwood’s The Last Banquet in which a natural scientist has a refined appetite for sensuous experience. Non-sexual questions include the best herbs to use with rat and the cooking time for tiger.

Peter Stothard

July 16, 2013

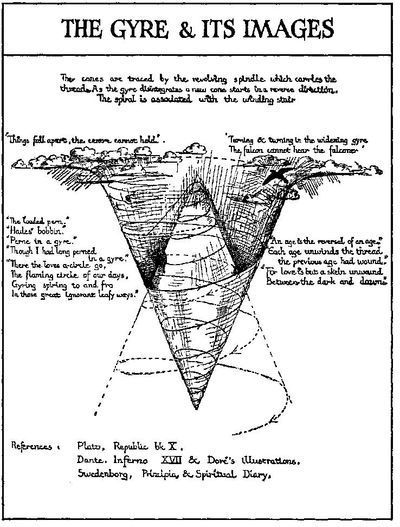

Do not use the word “gyre”

Sound advice for poets appeared in the TLS recently, in the form of “English Provincial Poetry” by Miles Burrows: the would-be versifier is counselled to refrain from quoting Dante as an epigraph (“This will look / Like pampas grass in front of a 1950s terraced house”) and given constructive suggestions about the objective correlative (“This could be a sunset, often a wild bird . . .”).

Also, Burrows advises: do not use the word “gyre”. “This can produce a severe reaction / In some readers. The same goes for ‘desolate’. . . ”.

How right he is. “Gyre”, however, has had many fans, going back beyond W. B. Yeats to Bishop Joseph Hall (who writes of the life of scholarship: “others run still in the same gyre to weariness, to satiety; our choice is infinite”), Edmund Spenser and Ben Jonson (who has now reached Huntingdon).

Yeats can perhaps only be blamed for the rise of “gyre” as a noun; it’s Lewis Carroll’s wabe-gyring (and wabe-gymbling) “slythy toves” who made it popularly quotable as a verb.

Taking a “route one” approach to its continued usage, Google’s Ngram Viewer suggests that there are now more gyres than ever.

Ah, that William Butler Yeats and that Lewis Carroll have a lot to answer for.

And in the TLS? There have been a fair few gyres one way and another over the years, many of them Yeats-related. Under that great influence, and going against all Burrows-derived wisdom, Ronald Bottrall put the word into a poem that also recalls Dante in its use of terza rima, “Anniversary”, in 1956:

By fire we are preserved from the foul gyre

That kindles, fridges and consumes its being

In selfish heat and cannibal desire.

But what if it’s 1967 and you’re trying to think up a headline for a review that begins with a whole paragraph about touring London in circles, “gyre by gyre as a pigeon plans its flights”? What headline would you give such a review?

Why, “Good Gyrations”, of course, in homage to the Beach Boys single released the previous autumn.

(Ah, headline writers have a lot to answer for, too.)

July 14, 2013

Thomas Hardy's sense of humour

By MICHAEL CAINES

That might sound like the title of a very short anthology. Or a startingly inaccurate piece of literary criticism. But don't let the received reputation of the author of Jude the Obscure deceive you. Readers of Angelique Richardson's lead piece on Hardy's letters in this week's TLS will learn that he in fact had "a fine sense of humour" and was, by one account, a "happy man".

He also had an "amused take on the advances of technology" – hence this footnote to Richardson's observations on the role of letters in Hardy's novels: as she says, letters play a significant part in The Mayor of Casterbridge and Tess of the d'Urbevilles, as they did in his own life; and it's "not only because . . . he couldn't hear anyone who rang" that the belated appearance of a telephone on the domestic scene didn't transform his habits of communication.

There's an earlier novel, however, in which letters see off another supposedly more technologically advanced form of communication – the telegram – only to prove insufficient for the correspondents' needs in turn. In A Laodicean (1881), the heroine Paula Power goes off to Nice with her "phlegmatic and obstinate" uncle Abner. That "breathing refrigerator", as her admirer George Somerset thinks of him, clearly wants to keep them apart – 900 miles apart. Since George has to remain at his post, overseeing the work of modernizing her home, Stancy Castle, how can he possibly keep up his burning expressions of love over that inconvenient distance?

Part of the fun is that George longs for effusions of love, whereas Paula, at their parting, is much more practical:

"I may write to you?" (George asks.)

"On business, yes. It will be necessary."

"How can you speak so at a time of parting!"

"Now, George – you see I say George, and not Mr. Somerset, and you may draw your own inference – don't be so morbid in your reproaches! I have informed you that you may write, or still better, telegraph, since the wire is so handy – on business. Well, of course, it is for you to judge whether you will add postscripts of another sort. . . ."

Once again, shortly before she steps into the carriage, Paula reminds him of the superiority of the (relatively) new technology ("Telegraphing will be quicker!"), before Hardy has some fun teasing George by raising doubts about her commitment to him – and the conviction that Abner is moving against him.

Then Hardy puts George through further torment as he tries to follow his beloved's instructions:

"One morning he set himself, by the help of John, to practise on the telegraph instrument, expecting a message. But though he watched the machine at every opportunity, or kept some other person on the alert in its neighbourhood, no message arrived to gratify him till after the lapse of nearly a fortnight."

The "meagre words" that arrive from Nice give no comfort to him, so he tries again:

"Will write particulars of our progress [i.e., the business side of things, the building work]. Always the same [i.e., the no-so-cryptic avowal of a constant lover]."

Then he writes a letter and receives a telegram of acknowledgement, promising a letter in due course – which, when it arrives, turns out to be, true to character, balanced between encouragement and elusiveness.

The correspondence continues – "Away southward like the swallow went the tender lines" – but culminates in a crisis, as the correspondents disagree over its purpose. "I am almost angry with you, George", Paula writes, "for being vexed because I will not make you a formal confession. Why should the verbal I love you be such a precious phrase?"

They revert to telegrams, the crisis (which is in some measure one of misinterpretation and silence) deepens, and, sure enough, and not to give much more away, George is soon on his way to the Continent, to try to put matters right between them face to face.

With Tess's letter under the carpet in mind, it may be that we're more apt to think of correspondence in Hardy's fiction as a cause of tragedy – if so, A Laodicean is the antidote. There are many sides to Thomas Hardy, as those newly published letters show, and, yes, one of them is humorous.

(But the poetry, you say – "The Darkling Thrush" and so on? Well, that's another matter . . . .)

July 12, 2013

Reading Saul Bellow

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I have a confession

to make: I have yet to read The

Adventures of Augie March. Published in 1953, Saul Bellow’s first “big”

book was described by Martin Amis, Bellow’s most eloquent and fervent

reader-critic, as “the great American novel”. No real excuse not to have read

it then.

But I have read all of Bellow’s other novels. Reading Bellow has been like a long, broken

but hugely rewarding journey. I first became acquainted with his work twenty-five years

ago, partly prompted by Anthony Burgess’s influential book Ninety-Nine Novels: The best in English since 1939. (Burgess’s

hope was that someone would choose one of his works as the 100th –

A Clockwork Orange perhaps?) Burgess

opted for Bellow’s The Victim as one

of his two best novels for the year 1947, the other one being Malcolm Lowry’s

Under the Volcano (not read). He called Bellow’s second novel a “quiet

masterpiece”. At the time, that seemed an accurate assessment. I’m sure it still

applies.

For some

unfathomable reason – what dictates our reading patterns?, I wonder – I didn’t

read another Bellow for a further three years or so: Something To Remember Me By, which included the novellas The Bellarosa Connection and A Theft, as well as the wonderful title

story of rites of passage in 1930s Chicago. But several more years passed

before I had a serious attack of the Bellows: the novella Seize the Day, More Die of

Heartbreak (great title, great book), Dangling

Man (his first), Herzog, The Actual, and Henderson the Rain King. I wasn’t at all persuaded by this last book,

but ploughed my way diligently through it. I’m still baffled by the high status

it’s accorded.

Amis’s first

published collection of essays The

Moronic Inferno and Other Visits to America (1986) took its title from Humboldt’s Gift (1975): “Now the moronic

inferno had caught up with me”, says the narrator Charlie Citrine as he surveys

the ruins of his swanky Mercedes which has been smashed up with baseball bats

outside his Chicago apartment.

Meanwhile, in his

memoir Experience, Amis writes, of

Bellow’s last novel Ravelstein

(2000), “I have to keep reminding myself that the author was born, not in 1950

but in 1915” (he died in 2005). There is indeed a remarkable energy to the

book, published in Bellow’s eighty-fifth year. The phenomenon of writers

remaining near the top of their game well into their eighties is still pretty

rare (and perhaps restricted to the twentieth and now the twenty-first century). If one

excludes poets, only a few names come to mind: the leading figure of the nouveau roman Nathalie Sarraute was

still near her best in her nineties. Her fellow nouveau romancier Claude Simon published one of his finest (and

briefest) works Le Tramway at the age

of eighty-eight – a sunny, captivating and fictionalized account of the novelist’s

childhood in a seaside town in the south-west of France.

On the debit side,

Philip Roth, who recently turned eighty, has declared that he will not be writing

any more fiction. The late Gore Vidal disappointed many of his readers with a

slackly written and woefully under-edited follow-up, Point to Point Navigation, to his fascinating, waspish memoir Palimpsest (1995). It might have been

better if the second book had not seen the light of day, particularly as it

turned out to be Vidal’s last work.

But Ravelstein doesn’t flag; as a homage to

and undisguised portrait of Bellow’s late friend the academic Allan Bloom,

whose best-selling book The Closing of

the American Mind was such a divisive work when it appeared in 1987, it

brings out the flamboyance and slight preposterousness of this larger-than-life

figure. Bellow clearly held Bloom in the highest regard, and at one point has his narrator compare him favourably with Diderot: “’The Palais Royal’ – Ravelstein

gestured loosely toward it – ‘was where Diderot walked late every afternoon and

where he had his famous conversations with Rameau’s nephew. But Ravelstein was

by no means like the nephew – that music teacher and sponger. He was above

Diderot, too. A much larger and graver person . . .”. Really?!

“The main thing

about Chicago is that it’s not New York”, wrote Bellow, of the two cities at

the heart of his work (Montreal might be a third). A blog is no place for lit

crit (and I’m no expert on American fiction) but it seems to me that if you

want to learn about life in twentieth-century urban America, and the Jewish

experience in particular, as well as much else too, Bellow’s work should be the

first port of call. And it might be said that his peculiarly European sensibility both expands and deepens its qualities.

And of course

there’s the humour: one of my favourite characters is the shameless Pierre Thaxter

in Humboldt’s Gift, a literary con man, serial

adulterer and father of nine, who travels across the

Atlantic on a liner in first class – his mother picks up the tab – in spite of

the fact that he’s flat broke (significantly, Thaxter is Californian). Citrine

tells him:

“If I had no

cash, I’d ask my mother to put me in steerage. How much do you tip when you

get off the France in Le Havre?” I

asked him.

“‘I give the chief

steward five bucks.”

“You’re lucky to

leave the boat alive.”

“Perfectly

adequate,” said Thaxter. “They bully the American rich and despise them

for their cowardice and ignorance.”

I have a Library of

America edition of Novels 1970–1982,

a period that represents the high point of Bellow’s career, the possessively

titled trio Mr. Sammler’s Planet, Humboldt’s Gift and The Dean’s December. One thing that struck me about this otherwise

very handsome volume is the extraordinary number of typos it contains,

particularly as the reader is assured that the “texts are presented without

change, except for the correction of typographical errors”. Here’s just a

sample selection: “Punisment”, “Sannnler” for Sammler, numerous “he”s for “be”s

and “be”s for “he”s, “staff” for stuff and so on, as well as the comical “New World Symophony” – none of them, granted,

an impediment to comprehension, but still . . . . I imagine these errors will

now remain uncorrected.

(Writing as someone

whose shared responsibilities at the TLS

include making sure the paper goes to bed with its hands as clean as possible,

i.e. proofreading the pages – the weekly equivalent of proofing a 50,000 word

novel – I always react to typos spotted too late as if I’ve taken a blow to the

solar plexus. I’m determined never to let through weirdly common misspellings

such as “elegaic” and “pharoah”.)

In her newly

published Literary Miniatures

(translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan; Seagull Books, $20/£13), a collection of

interviews with (non-French) authors, Florence Noiville, editor of foreign

fiction for the weekly supplement Le

Monde des Livres, describes meeting Bellow near his Vermont fastness in

1995. He greets her with the question “Suis-je celui que vous attendiez?” – “Am

I the one you were expecting?” It is strange to hear French spoken in this

remote inn in Vermont"; but it’s a reminder of Bellow’s early Montreal

upbringing, his Paris sojourn in the late 40s, and enduring Francophilia. Later in

the piece he reveals that “J. D. Salinger lives on the other side of these

hills, in New Hampshire. He’s a bear. Doesn’t see anyone. Never goes out. Worse

than I am”.

Now, on to Augie March.

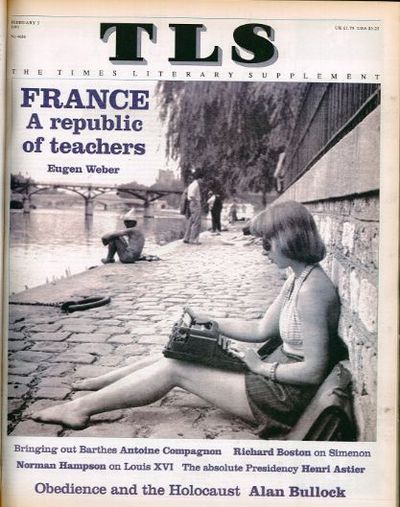

July 10, 2013

A small mystery solved

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Early in 1993 the TLS

published a French special issue with a cover image by Robert Doisneau of an

unidentified young woman sitting on one of the Parisian quais within sight of Notre Dame Cathedral, probably at work on her

first novel. How very French we thought, although one colleague did point out

that he would have found it irritating to have someone typing away near him in

a public space.

The identity of the young typist can be revealed. She is

Emma Smith, whose memoir As Green as

Grass (Bloomsbury) has just reached the TLS

offices. The photo appears inside as well as on the cover and is captioned “Summer

in Paris, working on The Far Cry and keeping

cool by the Seine during a heatwave, 1948”. The TLS, I’m happy to say, reviewed The

Far Cry in 1949, together with two other novels, including one by

Marghanita Laski: “Miss Emma Smith writes, in contrast to Miss Laski’s almost

masculine style, on a note of feminine sensibility, happily leavened by a sense

of the ridiculous which occasionally becomes humour . . . ; her first novel

marks a definite advance in her career, and if the influence of Miss Elizabeth

Bowen sometimes becomes perceptible, The

Far Cry is none the worse for it”. The novel went on to win the James Tait

Black Memorial Prize.

Think of Doisneau’s famous photo of the young lovers outside

the Hôtel de Ville in Paris: the young woman in that one was revealed to be

English too. A curious double for the photographer.

Emma Smith’s memoir will be reviewed in the TLS in due course.

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

The eighth volume of The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy includes

previously unpublished letters from all periods of the author’s life. The

previous seven were edited by Michael Millgate and Richard Purdy and

published between 1978 and 1988. The new volume, edited by Millgate and

Keith Wilson from new discoveries, contains insights into a wide range of

Hardy’s interests, from bicycles to booksellers, songbirds to cider,

feminism to the First World War. “Superbly edited and annotated”, in the

words of our reviewer, Angelique Richardson, it introduces new

correspondents, John Cowper Powys, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Lord

Kitchener, providing “a most absorbing volume for anyone who is interested

in the inner lives and outer worlds of the Victorians and the art of

letter-writing in which they excelled”.

The American poet Anthony Hecht, whose selected letters are reviewed by Adam

Kirsch this week, lived almost as long as Hardy, from 1923 to 2004. Kirsch

sees his defining years as those he spent as a combatant in the Second World

War, fighting in Europe and witnessing the liberation of a concentration

camp. This was experience that separated him from the slightly older

generation of Robert Lowell. Both men suffered from depression but, while

Lowell put the experience at the centre of his work, Hecht “made a conscious

decision to let the rational mind prevail”. The book contains intriguing

letters to the poet Anne Sexton, from the early 1960s, but no letters to his

wives.

When Nelson Mandela dies, we can expect many days of what Tom Lodge calls “the

uplifting narrative” of how the hero and his comrades led a “disciplined

rebellion” that eschewed violence in the spirit of “pragmatism and

idealism”. This “generally received version of the ANC’s history” is one

that is “long overdue for revision” and gets it in a book by Stephen Ellis

who notes, from the ANC’s own records, that its “leaders were by no means

reluctant warriors”. But Ellis “probably overstates the extent of the

Communist Party’s domination”.

Peter Stothard

July 8, 2013

On the Road (with Ben Jonson)

By MICHAEL CAINES

Ben Jonson’s London was a place where devils feared to tread. That much is clear from the first scene of his comedy The Devil Is an Ass, in which Satan, wary of maintaining Hell’s “reputation” among sophisticated metropolitan sinners, wonders if a “foolish spirit” called Pug ought not to be sent to Lancashire “or some parts of Northumberland” rather than the other place. “Stranger, and newer” forms of vice flourish there, and are “changed every hour”. True devilry can’t keep up.

On this day in 1618, Jonson himself got out of London: it was on July 8 that he set out on an expedition to Scotland, by foot. In general terms, this is territory Jonson had imagined, fifteen years earlier in an “Ode Allegorike”, coming under the flight path of a black swan, which unites King James’s kingdoms as it wings its way over them – from the “Hebrid Isles” and “scatter’d Orcades” to “Loumond lake, and Twedes blacke-springing fountaine”. Elsewhere, he alludes to Will Kemp who “Did dance the famous Morrisse, unto Norwich”.

Until recently, however, not much more could be said with any certainty about the poet’s own northern expedition, other than that it led to William Drummond of Hawthornden and his notorious notes on Jonson’s table talk: Shakespeare “wanted Arte”, Beaumont “loved too much himself and his own verses” etc. We now know a great deal more about it, however, thanks to a discovery reported by James Loxley in the TLS a few years ago.

Jonson, it turns out, had a travelling companion (identity currently unknown), a previously unsuspected Boswell to this Johnson without an “h”, who kept a manuscript account of what he called their “foot voyage” together. Whereas Drummond’s “Informations” about Jonson are all gossip and garrulity (about vermilioning Queen Elizabeth’s nose, among other things), the author of the foot voyage gives us dates and destinations, detours to Pontefract and Rufford Abbey, and encounters with a “network of friends and benefactors”. Noblemen receive them courteously; at Welbeck, “my Gossip made fat harry Ogle his Mistress”. . . .

Now – virtually at least – Professor Loxley and his collaborators, Julie Sanders and Anna Groundwater, are setting out in Jonson’s footsteps. From today until October 5, it will be possible to keep track of Jonson on the road, via Twitter and Facebook. Tonight, as they note on their blog, Jonson gets as far as Tottenham, after spending last night, “no doubt, at the Mermaid or Mitre in the City, or over at the Devil Tavern on Fleet Street”. It will be good for him, no doubt, to get away from those London devils. And good for any virtual camp-followers, too, now we have the Cambridge Edition of Ben Jonson (to be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS) and Ian Donaldson’s biography of “the dominant literary figure of his day” from which to draw further inspiration.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers