Peter Stothard's Blog, page 53

October 21, 2013

A weekend at Frieze

by ANNA VAUX

I went twice. No,

actually, four times if you count Frieze London and Frieze Masters separately,

which you probably should do since they are housed in separate venues, a fifteen-minute walk apart, and you

buy tickets separately – £32 per day

for each, though you can get a package deal: £50 for both. (I was

on a press ticket.) And I’ll probably go again before the four-day event is

over. How else can you take it all in, or even a fraction of it?: 152

exhibitors in one, 130 in the other, over 1,000 artists, from Tokyo, New York,

Berlin . . . from antiquity to yesterday.

How

can you see what’s what, especially at Frieze London, where I stood bewildered on the other side of the security, wondering which way to go, what to look at, right or

left? Thank goodness for Americans with loud voices, I thought, as I took a

steer from one shouting at another: SO many DRIPPY paintings this year! They

rushed determinedly by, surely on their way to somewhere, perhaps to where the

drippy paintings were because there were certainly none where I was standing:

traffic cones, totems, perspex discs, neon tubes, but no paintings, no DRIPPY

paintings, by which I’d imagined he had meant Jackson Pollock-y drippy.

But

perhaps he hadn’t, perhaps he’d just meant drippy as in “feeble” or “sad”, or even

“abject”. And I could maybe see his point as I wandered past a white clay block by Tracey Emin on which a weeny swan floated and into which she had scratched “HUMILIATION” in block capitals. Or her embroidered blanket into which is

sewn a rough sketch of a naked woman, her legs spread wide, and the words “You

made me Feel like nothing”. Or Ron Mueck’s hyperrealist miniature

sculpture of “Woman with Shopping”. Or Elaine Sturtevant’s video “Trilogy of

Transgression”, in which we get to see a vagina – or perhaps it’s a bottom – stuffed with a can of coke.

Then

again, perhaps the man was being ironic. Maybe it was a pose. A line. Because let’s

not forget how much art here is ironic, nor indeed how much people from the art world pose,

just how very fashionable they are, how much more glamour – how much more money – there is in the art world than

in the book world, whose chief event in London, the London Book Fair, was

recently described by the super agent Andrew Wylie as “like being in a primary

school in Lagos”. Just look at the clothes! The shoes! – in pony hair or calf

hair, shearling and suede, strapped and buckled, fringed and studded, wedged,

sculptured, sharpened, blocked. Nothing tired or abject or humiliated here,

unless perhaps you count the shoes the men at Frieze were wearing, shod like

infants with brightly coloured laces and neon soles. I half expected to see

their feet light up as they walked.

But

then, of course, the art at Frieze is not without its infantile side. Some of it

is actually made out of toys, I noted (or string, or sand, or flowers, leaves,

butterflies, driftwood). Some of it is made to look like toys, most notably the work of Jeff Koons, whose display features a shiny upside-down lobster like a beach

inflatable, a set of Tweety Pies swinging in a tyre, a metallic blue-wrapped Easter egg the size of a mobile home, which gave me a headache just to

look at it. For a second I felt bulimic, overstuffed with candy colour.

It

was a relief, then, to walk in the autumn sunshine through Regent’s Park for a

cleansing fifteen minutes, up the gently sloping ramp to Frieze Masters, where

it’s all grey carpeted avenues, low lighting – and quiet. Elegant couples sat

in Marcel Breuer chairs; low tables supported ice buckets, bottles of

champagne. Men in dark suits paced softly, speaking quietly but firmly into

their mobiles. Ah, so this is what money sounds like, I thought. And it’s

mostly French! Non, non, Cherie, je suis

a Frieze . . . plus tard, mon brave, parce que maintenant je suis a Frieze . . . .

The art here seemed wonderfully hushed and still: abstract work in

dull whites, browns, greys, Robert Motherwell, Robert Ryman, Mira Schendel, pen

and inks by Matisse, a huge piece by Richard Long constructed of pale stone. The colour, when it comes, is quite astonishing: the yellows and oranges of a

stunning Josef Albers, green, black and orange in a tiny Gerhard Richter, Dan

Flavin’s fluorescent tubing, small, vibrant Picassos, a vase and an apple, a cup

and a teapot, like jewels, Alexander Calder, Joseph Kosuth, Martin Barré. Rows and rows of extremely beautiful

art. A stand where I wanted everything: Lygia Clark, Mary Martin, Jeffrey

Steele, Bill Culbert, Franz Weissmann . . . . This must be the most beautiful

place in London, I thought for a moment.

At

least, that’s what I thought that day. It was different when I went the next

time. I suppose each of the four days has a different flavour, a different

timbre, and Friday afternoon at Frieze Masters seemed a little tired – and a

lot more Italian. I sat for a while on the plush circular seating near where

you come in (and go out). If I come back, I thought, I’ll look at more, at the

Philip Gustons I’d missed, at the Bob Laws, back to the stand where I’d wanted

everything. I thought of the Yayoi Kusama piece, which had rewarded me for my

fetishism, with fifty pairs of ghostly white shoes stuffed with soft phallus

like forms. My own feet were tired. I looked down at them. (Clogs, I expect,

will be big next year.) Looking at art is exhausting. And buying and selling

art must raise quite a sweat. People were queuing for cups of tea at the café.

The tables were full.

This

tent did not have the stamina of the other, which, it became clear to me when I

went back, could party all night, especially on a Friday. Back in there I leant

against a panelled wall and scribbled on the back of an envelope. Americans

were planning their evening (at Shoreditch House). A dark-haired model in an Alexander

McQueen dress walked by with her entourage. There was a smell of face powder

and hairspray. She was “interviewing artists”, I overheard. No expertise

needed. Perhaps it doesn’t matter what anybody thinks or says. “She’s

definitely going to win the Turner Prize”, I heard someone say in front of a

display by an artist who is not, as it happens, on the shortlist for this

year’s Turner Prize.

On

the way out, the security man checked my bag thoroughly, long fingers

separating the pages of a folded newspaper, a small torch illuminating the

inside of my Frieze press pack. “No stolen artworks in there!”, he chortled,

which gave me pause for thought. I mean, I probably could have got away with a

small piece from Frieze Masters. I probably should have. But I’d never get away

with my favourite piece from Frieze London, “Four in a Dress” by James Lee

Byars, in which four people sit on a plinth holding hands underneath a black silk

valance up to their necks, in quiet conversation. It would be funny if it

didn’t look so tragic.

October 18, 2013

Does anyone have a good word to say for the critic?

Does anyone have a good word to say for the critic? “Asking a working writer what he thinks about critics is like asking a lamp post how it feels about dogs.” So said the screenwriter Christopher Hampton in 1977, the year that saw the release of a now-forgotten, perhaps ill-reviewed, film Abe’s Year. In Brendan Behan’s view, critics are like “eunuchs in a harem”: they know how it’s done, “but they are unable to do it themselves”. The literary critic, said Cyril Connolly, unendearingly, had “the thankless task of drowning other people’s kittens”. Can we rely on Kenneth Tynan, himself a famous critic, to elevate the critic’s position? Sadly, not. “A critic is a man who knows the way but cannot drive the car.”

These remarks are reported in the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, edited by Gyles Brandreth. Theatre critics are particularly unpopular, since the hard work of many vigorous thespians can be undone by the groan – squeal? – of a single eunuch. The characteristic sound of a Sunday morning, said one casualty, is that of Harold Hobson (drama critic for the Sunday Times) barking up the wrong tree.

It is conveniently forgotten that without the harmful drudge scribbling in the stalls, all the dramatist’s great work might go unnoticed, unremarked, unrecorded. And who has not felt like Groucho Marx: “I didn’t like the play, but then I saw it under adverse conditions – the curtain was up”. Or Dorothy Parker: “House Beautiful is play lousy”. Or Noël Coward watching Lionel Bart’s musical Blitz: “As long as the real thing, and twice as noisy”.

To qualify for inclusion in Mr Brandreth’s Dictionary, “you have got to make the editor laugh. Or smile”. Most readers will smile frequently, but we frowned whenever we saw the word “attributed” after a quotation (about drowning kittens, for example). Most of us have had remarks attributed to us that we never made. And, more rarely, remarks we wish we had made. John McEnroe said, “The older I get, the better I used to be”, which we thought was witty of Mac, until we learned that he was quoting the basketball player Connie Hawkins. You might think we’ve just caught Mr Brandreth out there, but in fact he provides the information himself.

The only species with less claim to sympathy than the critic is the male. The Dictionary has a section on men’s foibles, some of it humorous: “Most men think monogamy is something you make dining-room tables out of” (Kathy Lette). The corresponding section on “Women and Woman’s Role” – start feeling the sympathy right now – contains some equally disobliging comment . . . about men. This, too, is often humorous. “The trouble with some women is that they get all excited about nothing – and then marry him” (Cher). The Dictionary of Humorous Quotations (OUP) costs £20.

J. C.

An extract from the NB column in this week's TLS. Picture © Chris Joyce.

October 16, 2013

In this week's TLS – a note from Deputy Editor

Love of innovative gadgetry and pleasure in gee-whiz devices might be a defining feature of our times, but Jules Verne was making them the basis of his most popular works from the 1860s on. Did he, though, in common with Robert Louis Stevenson and William Morris, come to see “the vast nineteenth-century expansion of human knowledge and power” as a dystopic Eden, whose troubling outgrowths included unpredictability, uncertainty, “loss and calamity”? A new study argues that they did; our reviewer Felipe Fernández-Armesto, while he finds the book an “irresistible, endlessly instructive pleasure”, is not so sure. It closes with a vision of “rolling apocalypse”, humankind self-condemned by reckless exploitation of nature. The achievements of Frank (F. P.) Ramsey, dead at the age of twenty-six, have been entirely overshadowed by those of Ludwig Wittgenstein, yet it is Ramsey who – according to David Papineau, reviewing a memoir by Ramsey’s sister – “singlehandedly forged the ideas that have come to dominate the philosophical landscape”. For Wittgenstein, “science was an enemy that threatened to coarsen the human spirit. For Ramsey, it was a friend that could help us understand the place of humans in a world governed by natural law”. Paul Bishop, meanwhile, reviews a selection from the work of another forgotten philosopher, and another Ludwig: Ludwig Klages, whose address to German Youth in 1913 was “arguably a founding document of the Green Movement”, and who offers a persuasive version of what it is to be “truly alive”.

To be truly alive – to feel all “the joy of living”, with its attendant risks – is one of the great themes of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, which is also “one of the great plays about syphilis”, as Sue Prideaux says. Syphilis was widely considered a hereditary disease; Prideaux’s Commentary offers fascinating insights into how and why Ibsen probably knew better. Paul Binding reviews a production that is the first since 1906 to make use of Edvard Munch’s set designs for the play.

Alan Jenkins

October 15, 2013

Four Four Jew

by TOBY LICHTIG

"With the exception of a few minor skirmishes which took place about a quarter of a mile from the Tottenham Football Ground and which were promptly broken up by the police . . . the match at White Hart Lane on Wednesday passed off without any scenes worth mentioning."

The year was 1935 and the match in question was an international friendly between England and Germany. The choice of Tottenham as the venue – with its large coterie of Jewish fans – was highly controversial. Pleas to keep politics out of football were roundly ignored. "Although it was stated that the German supporters would not have flags, there were hundreds of small swastika flags waved by them at exciting moments", reported the Jewish Chronicle.

An astonishing 10,000 Germans arrived in England for the match, and many were taken on tours of the capital. Of the 800 London guides employed for the occasion, 150 were said to be German Jewish refugees. "The guides were given strict instructions not to answer any personal or political questions . . . and on no account to take the trippers near the Whitechapel district." Ten months before the Battle of Cable Street, the Chronicle's correspondent noticed a German wearing a "badge of a Union Jack with fasces on it" and wondered "just how close a contact there must be between Nazism and Mosley Fascism in England".

This original article is one of many fascinating exhibits currently on show at the cutely proportioned and cutely entitled Four Four Jew exhibition at the Jewish Museum in London. (It's worth noting that, in Cockney parlance, the People of the Book were once referred to as "four by twos".) The exhibition – which was last week opened by Arsène Wenger – aims to "re-imagine football as a surrogate religion whose passion and tribal spirit have played an integral role in shaping British Jewish identity from the 1900s to the present day".

Whether it succeeds in this is anybody's guess, but a century of Jewish contribution to – and obsession with – British football has been documented with loving attention. As well as the (admittedly limited) role of professional Jewish players and managers, including David Pleat, Barry Silkman, Mark Lazarus, the observant Harry "Abe" Morris – Swindon's record marksman and the seventeenth highest goalscorer of all time in England – and a selection of latter-day Israeli footballers (Avi Cohen, "Rocket" Ronny Rosenthal, Eyal Berkovic, Yossi Benayoun, Tal Ben Haim), the exhibition looks at the parts played by various Jewish board members, policy makers, representatives of the FA (whose current chairman, David Bernstein, and predecessor, Lord Triesman, are both Jewish) and, of course, fans.

There is a wealth of memorabilia – programmes, scarves, kippot emblazoned with club crests – and intriguing documents, including an excerpt from a 1965 Arsenal programme giving notice of a late kick off "in order to assist our many Jewish supporters who will be observing Rosh Hashana" and yellowed newspaper correspondence regarding the fraught question of attendance on the Sabbath. One fan reasons thus: "I don't pay. I am a season-ticket holder . . . and when I enter the Arsenal ground on Sabbath it is the same as if I were entering a public park, since no money changes hands".

Other controversies include a 1943 "plan for the inculcation of Judaism in Jewish clubs" (the one religion was feared to be superseding the other), indignation at Manchester City's signing of a German goalkeeper (Bert Trautmann) in 1949 – Rabbi Alexander Altman called on Jews "not to punish an individual German who is unconnected with [Hitler's] crimes" – and the current flare-up about the use of the word "Yid" at Tottenham Hotspur: once a mark of Jewish solidarity ("the highest honour that any player at White Hart Lane can have bestowed on him", according to the Guardian's John Crace), it now feels increasingly outdated, distasteful and open to abuse.

We are also reminded that the now-extinct Jewish club Wingate FC was named after the Christian army officer Orde Wingate, who trained up the Jewish paramilitary organization, the Hagadah, in British Mandate Palestine. "Our version of [T. E.] Lawrence, crazy Orde, a goysiher Zionist", writes the author, TLS contributor and boyhood Wingate fan Clive Sinclair in his short story "Wingate Football Club" (1979), a signed limited edition of which is on sale at the exhibition and £3 shrewdly spent.

Four Four Jew is curated by Joanne Rosenthal in conjunction with various advisors, including Anthony Clavane, whose recent book Does Your Rabbi Know You're Here?, explores similar themes. It runs until February 23, 2014 and anyone interested in British Jewry, football culture and the surprisingly nifty interplay between the two is advised to drop in and take a look.

October 11, 2013

French literary anniversaries, part 3: Camus

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In this week’s TLS, Robert Zaretsky reviews Albert Camus’s Algerian Chronicles, a collection of the Nobel Prize-winning

author’s journalism, both early and late, in a “brilliant translation” by

Arthur Goldhammer. Zaretsky writes that Algeria’s right to independence from

France was complicated in Camus’s mind by the fact that he was himself one of a

million French colonists – “the dilemma he could never resolve”. The book’s publication marks the

centenary of Camus’s birth (November 7, 1913).

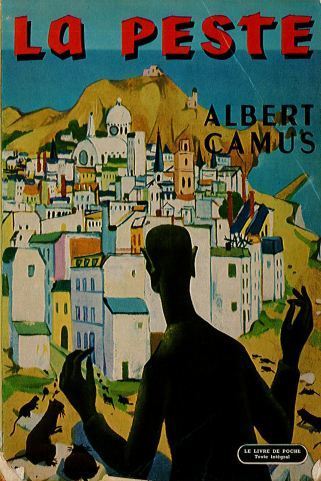

It’s probably safe to assume that it

was mainly Camus’s work as a novelist and playwright that won him that Nobel

Prize in 1957, “for his important literary production, which with

clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in

our times": L’Étranger, La Peste and La Chute in particular. (Does anyone concern themselves much with

the plays these days? The theatre doesn’t seem to have been his natural

medium.)

In common with many readers, I have

always found it easier to read (and admire) Camus than Sartre – the two will

forever be indissolubly linked, thanks to their active presence on the post-war

Left Bank. Camus was the humanist, Sartre the ideologue, Camus the

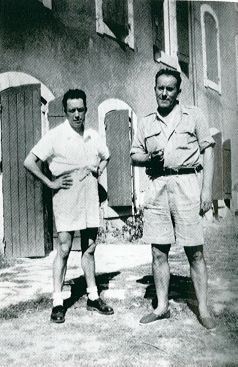

sensualist, Sartre the intellectual and so on. Camus had the better look: the

upturned coat collar and the fag stub (although my favourite photo of the

author has him wearing improbably high shorts, below, with the poet René Char).

But what of Camus’s fiction now? I for

one won’t be reading L’Étranger (The Outsider) again, brief though it is;

the last time I read the book it left a rather unpleasant taste, right from its

notorious opening two sentences: “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne

sais pas”. Reviewing a new translation of the book in the TLS last year, Shaun Whiteside mused: “. . . how strange this novel

now seems. Camus’s Algiers of seventy years ago is a bizarre non-lieu, a European city peopled by

Europeans, where shady anonymous ‘Arabs’ lurk menacingly in the background”. It

did, however, inspire a good song by The Cure.

I have just reread La Peste (1947; The Plague). According to its author, “La Peste may be read in three different ways. It is at the same

time a tale about an epidemic, a symbol of Nazi occupation . . . , and,

thirdly, the concrete illustration of a metaphysical problem, that of evil . .

. “. The symbolic interpretation doesn’t persuade me: the allegory is so vague – are we really to

believe that the rats bringing the bubonic plague to the Algerian coastal town

of Oran are in fact Nazis occupying France? I prefer to read it on a literal

level, as an account of human suffering under terrible conditions, but also of

the strength of the moral and physical courage of some, as well as the stoicism

of others: the saintly doctor, Rieux, who doesn’t have time to worry about his

sick wife who has been sent away on a health cure, and who visits an aged

asthmatic at 10 at night, and his associate Tarrou who accepts his fate with

dignity. It remains a powerful book, and almost painful to read in places: the

description of the death from the plague of a young boy in particular. At times

it’s as if Camus is presenting a world without the possibility of redemption,

while the nature of evil could be said to be explored through the figure of

Cottard, a petty crook profiting from the crisis and happy to see its

continuation.

But again it’s hard not to be struck

by the Europeanness of Camus’s Oran: a Jesuit priest delivers a sermon in which

he places the blame for the plague on its victims; because of the plague, “everyone” in Oran has

forgotten about Christmas this year. Arabs are conspicuous by their absence. This was the world Camus mainly knew.

Camus’s biographer Olivier Todd wrote

that “La Peste’s calm and ample style

was radically different from the terse and dry tone of L’Étranger. It was similar to a lake after a

torrent”. The book was favourably received, although not in Camus’s own

publication Combat, ironically, where

Maurice Nadeau criticized the author’s notions of secular sainthood. Fifty-two

thousand copies were sold within a few months (according to Todd, Sartre, on a

lecture tour of the US, “publicly praised La

Peste and its author’s talent, but privately he declared that Camus was no

genius”!)

Against that, Sartre

called La Chute (1956, The Fall) “the finest and least well

understood of Camus’s works”. Its English translator Robin Buss said that “for

many, it is the best and the most original thing [Camus] wrote”. A bleak autobiographical

meditation set in Amsterdam, it remains worth reading.

As is the

posthumously published Le Premier Homme

(The First Man, 1994), a novel

reconstructed by the novelist’s daughter Catherine Camus from manuscript pages found scattered across the road after the car crash that killed him

on January 4, 1960). In fact, it’s hard not to see it as Camus’s best work, a

moving reconstruction of the history of colonial Algeria from 1830, when the

French first arrived, seen through the eyes of a poverty-stricken family of

settlers (the author drew on his own family’s harsh experiences).

An exhibition, Albert Camus, citoyen du monde, has just opened in Aix-en-Provence.

Writing about it in Le Monde (October

8), Macha Séry explains how the original curator Benjamin Stora was thrown off

the project last year because of his critical views about colonial Algeria,

which didn’t chime with those of the Aixois old-timers who were nostalgic for

French Algeria and happened to be close to the city’s mayor Maryse

Joissains-Masini.

Séry writes: “. . . what’s astonishing

is the extent to which Albert Camus, the best-selling French author outside

France, remains unappreciated in the Hexagon [France]”. She reveals that,

unlike his near-contemporaries Sartre, Boris Vian and Guy Debord, he has never

been dignified with an exhibition at the Bibliothèque nationale. Which is

“incredible, a real mystery”, according to the leading French publisher Antoine

Gallimard (another member of the Gallimard clan, Michel, was at the wheel of

the fancy Facel Vega when he and Camus were killed).

Complex, combative, morally tormented,

Camus, it seems, continues to divide opinion.

October 10, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

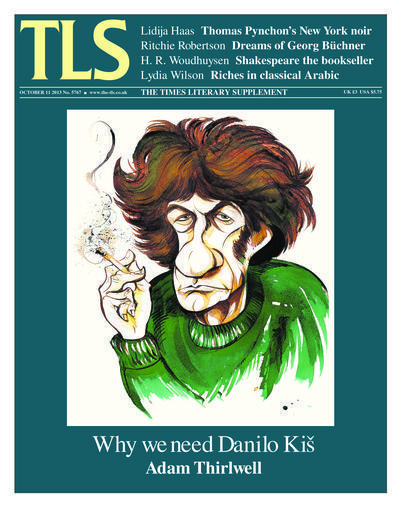

How can one restore justice to Danilo

Kiš? – is the question that preoccupies Kiš’s fellow novelist Adam

Thirlwell this week, though the “comprehensive, erudite and stylish

biography” he reviews might be a start. Kiš, born in 1935 in what was then

Yugoslavia, dying in exile in Paris at the age of fifty-four, of lung cancer

(“a man writes so that he can smoke”, he said), was one of a

“great global generation” of writers that includes Thomas Bernhard, Milan

Kundera, Thomas Pynchon and Mario Vargas Llosa – but unlike them he has “no

global existence”. Yet he is, we hear, “necessary for a future literature ”.

This week’s issue, coinciding with the Frankfurt Book Fair where so many

writers’ global existence has begun, pays special attention to literature in

foreign languages, some already translated into English and some yet to be:

the letters of Julio Cortázar, that show his progression from respected

author to intellectual hot property; a new and “different kind of” biography

of Georg Büchner; Albert

Camus’s Algerian Chronicles, “both timeless and timely”; The

Arrière-Pays by Yves Bonnefoy (“the French expression has been

retained, with the author’s approval, for want of an adequate English

equivalent”); essays by W. G. Sebald and Alexander Herzen (for the first

time, anglophone readers can hear “all Herzen’s voices speak for

themselves”).

[image error]

Thomas Pynchon’s new novel is full of “period detail”, the period being the

recent past – the spring of 2001, “the moment just after the bursting of the

dotcom bubble” – and the place New York, whose immediate future is

foreknown. Lidija Haas enjoys the book’s “vast, paranoiac set of systems,

the everything-is-connected, nothing-is-what-it-seems quality”. Lydia

Wilson, meanwhile, salutes The Library of Arabic Literature, a remarkable

project of editing, translating and publishing that will do for pre-modern

Arabic texts what the famous Loeb Library has done for the Classics, and

promises to “revolutionize” the study of medieval Arabic thought and

literary creativity.

Alan Jenkins

October 9, 2013

not-the-hundred-best-novels

October 8, 2013

Should the TLS review children’s books?

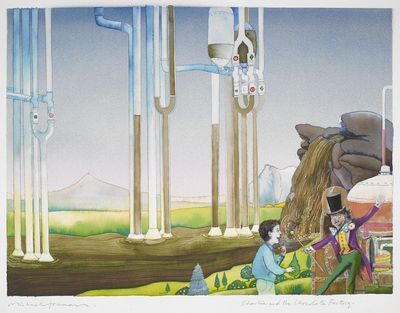

Illustration from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl. Published by George Allen and Unwin. Illustration © Michael Foreman, 1985

By MICHAEL CAINES

Should the TLS review children's books? Because it certainly used to – and here, at the editorial office, we still irregularly receive a few "books for the young", as they were sometimes called when the TLS did carry such reviews. There's nothing we can do with them now, however, since the responses to two reader surveys in the 1990s led to such reviews being discontinued. I wonder what readers think twenty years on.

The question is prompted by the British Library's new free exhibition in the Folio Gallery, Picture This: Children's illustrated classics, which opened last Friday, and which features some children's classics (as if talking about fortysomethings' or pensioners' classics is the norm) that the TLS did review.

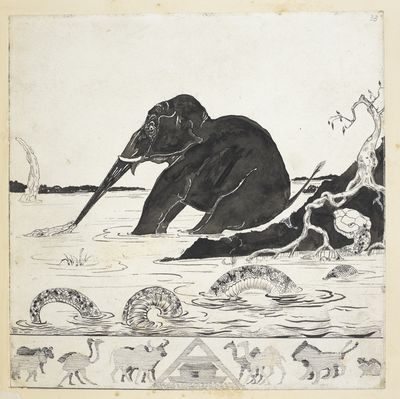

One of the earliest reviews of all, for example, in issue no. 38 (October 3, 1902), took note of Kipling's "healthy, humorous, quite unmawkish" Just So Stories, and makes the point that "No writer of a book for children but lets slip something of his views on education"; does the same hold true today for the likes of Michael Morpurgo, Michael Rosen, J. K. Rowling et al? The reviewer also took a liking to Kipling's own "vigorous" illustrations in black and white, which Kipling himself would have preferred to see in colour. Uncoloured, however, "every line is full of humour and spirit", as in this view of the Elephant's Child in the grip of the Crocodile's "musky, tusky mouth":

Autograph printer's copy of "The Elephant's Child", Just So Stories. Illustrations by Rudyard Kipling © British Library Board

The paper later caught up with Roald Dahl's James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory simultaneously, in 1967, enjoying both very much, although finding the writing in Charlie "more frantic" and "attention-grabbing" than in James. The verses were good, though. "Good illustrations, too." (Above is a "re-illustration" by Michael Foreman from the 1980s.)

On the same page, incidentally, there's a single sentence thumbs-up for Ralph Steadman's Jelly Book, demonstrating a traditional method of testing out an adult opinion against those of younger readers:

"If the children at Westminster Children's Hospital (to whom this book is dedicated) laugh as much as two boys of five and seven have at this, all hospitals had better invest in a copy . . . ."

But spontaneity of response isn't the only test. In an appreciative account of Moominland Midwinter, nine years earlier, Edward Blishen marvelled at the language Tove Jansson and her translator Thomas Warburton used, such as her description, on the second page, of night as being "deep and expectant", and a blizzard as "a bewitched whirl of damp and dancing darkness". "Very difficult indeed", Blishen judged, "for many sevens and eights: not easy, for many nines and tens." But if children needed adult assistance with the book, the adult might be pleasantly surprised, too: "there is always a sense", he wrote, "in which a commentary on real life is implied; especially, here, in the wonderful skiing Hemulen, who is the clumsy hearty set down among creatures more shy and private than himself".

October 4, 2013

Ceci n’est pas un supplement

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Ceci n’est pas un blog, either. It is a declaration. We, the Times Literary Supplement, are not a supplement. We are a separate and autonomous publication, with its own front cover and its own back page.

The latest to struggle with this well-established state of affairs is Anne Robinson, alias “The Queen of Mean” on BBC One’s long-running daytime quiz show The Weakest Link. The slip-up was brought to my attention (I was not watching the programme, you understand) after yesterday’s episode in which a contestant was asked: “In newspaper publishing, a weekly supplement to The Times is the TLS, which stands for Times what?” (“Pass”, said Jonathan, a twenty-eight-year-old commercial financial assistant from York).

Of course, I can understand why many might jump to the same conclusion. Oh the treachery of our title! Yet, as a former journalist – with a stint on the Sunday Times no less – one might have expected Anne to get this right. So, Anne, this is for you – a history of the TLS en bref:

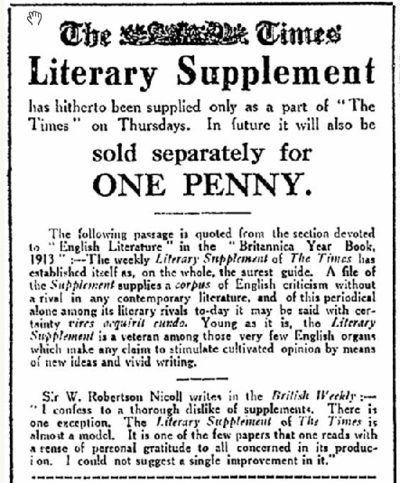

The Times Literary Supplement began its life in 1902 as a weekly supplement (yes) to The Times newspaper. But, with Bruce Richmond – the paper’s longest-serving editor to date (thirty-five years) – at the helm, we parted ways, slowly at first. The paper continued to be given out with The Times for a few weeks, but with this notice:

And then, the cord was cut good and proper. That was in 1914, so next year will, in fact, be the 100th anniversary of our rebirth as a non-supplement.

The year gives some indication of the reasons for the schism. As The Times gave over page after page to reports from the Continent and parliamentary coverage from down the road, the “Lit Supp.” was keen that the books piling up in their small corner of the office be valued for more than their potential as barricade material – which is not to say that Richmond and his contributors were deaf to political developments.

On the contrary, in the wake of the declaration of war on August 4, the newly autonomous TLS led with an in-depth round-up of recent books to provide readers with a real understanding of “the crisis”.

Cited in Derwent May’s Critical Times is a letter from Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times among other papers, to Geoffrey Robinson, then editor of The Times, in which he seems to hold the TLS accountable for a – surely different? – crisis:

“I certainly consider that the Literary Supplement is one of those things which is causing the lamentable figures that are presented to me every day, and which will sooner or later bring about the great crisis”. (But who knows what the man who decided to market The Times as “The Easiest Paper To Read” really intended.)

So, you see, describing the TLS as a supplement to The Times is a bit like describing the Vatican as just another part of Rome: found not far from the old centre, revered by some – no doubt loathed by others – and full of culture and history, involved in politics and economics . . . . Not that I wish to take this analogy any further.

Perhaps, after all, Jonathan-from-York’s “pass” was, in fact, a quiet iteration of defiance.

October 3, 2013

Jeremies in the studio

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Dystopian novels on the whole are not my thing –

there’s enough misery in the real world as it is. Nor do I read thrillers very

often. But I was recently sent a book that falls into both categories and that

I found hard to put down: A State of Fear,

which was published earlier this year (320pp. Gibson Square. Paperback, £9.99).

The author (whom I know a little) published it under the pseudonym Joseph Clyde

and the book came with the cheering message “Enjoy – if you can”.

A

State of Fear imagines Britain after the explosion of

a dirty bomb at the entrance to the Bank of England in the City – an act of reprisal carried

out by an al Qaeda cell (two brothers in this case) for the assassination of Osama bin Laden (a planned simultaneous attack in New York is foiled). In addition to the hundreds killed

by the impact (we never find out exactly how many), the wind is blowing

radiation dust eastwards across the city, with the result that large-scale

evacuations have to be carried out. And then there is the anxiety over the

prospect of a second bomb. Indeed, “the Syrian” and his sidekick, a Trinidadian Muslim convert called Jayson, are planning just that, thereby giving the book real tension.

I guess that a thriller stands or falls by its

plausibility: recent intelligence failures in Nairobi, before that in Mumbai in

2008, and further back than that . . , mean that this book has a certain grim topicality. The author's message is: this could happen, in London – even after the attacks of July 2005.

Caught up near the incident is Julie, a doctor whose

daughter attends a primary school in Aldgate, on the eastern fringes of the City, and who may have been exposed to

the fallout in the school playground. Julie already has plenty on her plate: she is seeking a divorce from her

husband Martin, a curiously indecisive journalist who becomes scarily and

unavoidably embroiled with some revenge-seeking white fascists – “‘Fuckin’

country can be zinging with radioactivity and the Jeremies will be in their

studios doin’ in-depth interviews with their Muslim scholars, so-called’”.

Julie and her daughter are relocated to Sheringham,

on the north Norfolk coast, where the clifftop campsites fill up with increasingly

atomized population groups from London. The real victim of the story – and its

most sympathetic character – is undoubtedly the naïve younger sister of the two

bombers, Safia, who grows up in a deeply misogynistic household and is horribly

duped by her brothers. Her trial on

charges of being accessory to mass murder is particularly well done.

Into the mix the author throws criminally inclined

Russians and Ukrainians: the bullying Mrs Marusak, who runs a beauty salon in the

City . . . and a brothel upstairs, and drinks large Cointreau cocktails; her

boyfriend the thuggish Sergei, whose order to the wine waiter goes

“Give me two bottle. Of this” (this being Chateau Liversan ’82). And the book

is stylishly written, with neat flourishes: “Freeing his arm M. Denizet moved

resolutely away, proving once again that French is the perfect language in

which to discontinue a conversation”.

The historian Michael Burleigh is quoted on the

cover describing the book as “Dark, fast, pitch-perfect”, and again on the back to say that

it “has a firm grip on the subterranean currents at work in our society”. The publishers tell us that “Joseph Clyde’s work as a diplomat

involved him closely with the intelligence and security services”. In writing this novel he appears to have made judicious use of those

connections. What have they made of it I wonder.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers