Peter Stothard's Blog, page 49

January 4, 2014

In the first TLS of 2014 – a note from the Deputy Editor

Plots were “problems not proofs” for nineteenth-century geologists, according to a new study of an emerging science and the fiction it had little time for. Even so, there were occasions, our reviewer Trev Broughton writes, when geology yielded to “the enchantment of romance”, not least in its practitioners’ sense of their own “heroic questing” – and their partiality to the works of Sir Walter Scott. Dr Broughton also reviews the new Cambridge History of the English Novel, in which“the stubborn influence of romance, and of Scott especially”, is a connecting thread. And Scott naturally figures – though not largely enough, in A. N. Wilson’s view – in a book about the Victorian invention of the British past: one that served “a self-myth of self-improvement”. It was a fabrication, furthermore, that “no more implied antiquarian reverence than does the reproduction of the Roman Forum in Las Vegas”.

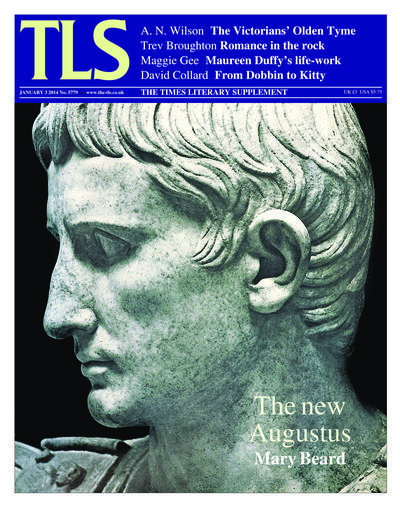

This first issue of 2014 finds our own Mary Beard, not in Las Vegas and not (or not quite) in the Forum, but in Rome nevertheless: at the exhibition Augusto. Looking back to an earlier Augustan extravaganza, which was opened by Benito Mussolini in 1937 and marked the 2,000th anniversary of the first emperor’s birth, she finds this commemoration of his death concerned to distance itself from its Fascist forebear. Augusto celebrates the artistic achievements of the Augustan age; it gathers together “in one place more of the most significant, original works of art of Augustus’ reign than have ever been assembled before – even in the ancient world itself”, and offers “a stunning introduction to the very best that Rome could produce”. And yet, Professor Beard concludes, “it is hard to resist the idea that Augustus might have liked the way Mussolini’s exhibition presented him”. Joseph Luzzi reviews a new translation of Pleasure by Gabriele D’Annunzio which helps us to enter that writer’s “museum-like imagination”. Out of a very different Italy – via Stanford – comes the scholar and critic Franco Moretti, whose “remarkable trajectory” is described by David Winters.

Alan Jenkins

January 2, 2014

Jacques Kallis and the lower-case Test

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This blog seems to be oscillating predictably in its choice of subjects between French literature and cricket. I really ought to get out more.

The South African all-rounder Jacques Kallis retired from Test cricket earlier this week, signing off with a century – his 45th – against India in Durban, thereby helping his team to victory (South Africa are the 1st ranked team in the world and India the second, so it was a significant win). England, meanwhile, appear on the brink of a 5–0 drubbing by Australia.

Kallis’s contribution to his country’s cricketing success at the longer form of the game has been immense: over an eighteen-year career (he made his debut at the age of twenty) and 166 Tests, he has scored 13,289 runs at an average of 55.37, taken 200 catches (mostly at slip I imagine – “hands like buckets”, as they say) and 292 wickets at 32. These are staggering statistics. His tally of 97 sixes meanwhile puts him second behind only Australia’s Adam Gilchrist in that field and belies the notion of him as a dour play-safe accumulator of runs: he could be destructive when the situation demanded it. In fact, we are looking at of one of the most complete cricketers to have played the game: an indomitable, occasionally bullying batsman, superb slip fielder and aggressive and effective medium-fast swing bowler.

I write as someone who made a fool of myself with a letter to the TLS’s rival publication the London Review of Books back in October 2005, in response to an article by David Runciman about England’s momentous triumph over Australia in that summer’s Ashes series. Runciman had compared England’s man of the summer Andrew Flintoff unfavourably as an all-rounder with Kallis and I took objection. The letter (published) is here in full:

“David Runciman compares Andrew Flintoff’s record as an all-rounder unfavourably with that of the South African Jacques Kallis. It’s true that Flintoff’s batting and bowling averages (33 and 32 respectively) are inferior to Kallis’s 56 and 31, but comparisons of the two players’ records in matches against Australia are instructive: in his five tests against them so far Flintoff has scored 400 runs at an average of 40 and taken 24 wickets at 27 each, whereas Kallis, in 12 tests against Australia, averages 32 with the bat and has taken a mere 22 wickets at 39 each. Kallis’s test batting average of 56 against all-comers is admittedly impressive, but the dour South African has a reputation for gorging himself on weak Zimbabwean and Bangladeshi bowling. Also, Flintoff scores his runs at 67 per 100 balls, whereas Kallis manages a rather more Boycottian 42 per 100 balls.”

That probably felt clever at the time but time didn’t vindicate me as Flintoff never reached those heights again. I did witness his last significant act for England, in his final Test at the Oval in August 2009, where he ran out Australia’s No 3 Ricky Ponting with an Exocet of a throw from mid-off, thereby snuffing out Australia’s slim chance of victory and ensuring that England would have the Ashes. I have never seen a cricket ball thrown so hard and I swear that had it not splattered the stumps it would have carried on at a frightening speed towards where we were sitting. Flintoff, ever the showman. raised his arms in a trademark gesture of triumph, while Ponting could barely drag himself away from the crease.

Kallis has never, as far as I’m aware, quite displayed Flintoff’s flamboyance but it’s clear that his record is far superior to the Englishman’s, and he managed to up his strike rate from 42 runs per 100 balls to nearly 46, while Flintoff’s dropped by the end to 62. (I eat humble pie and will refrain, after this blog, from pronouncing on things I know next to nothing about.)

When I later endured watching England bat against South Africa, again at the Oval (in 2012) Kallis was the best bowler on show, which, given that South Africa have the most potent bowling attack in world cricket, was pretty impressive (he bounced Kevin Pietersen out). For good measure he scored 182 not out and South Africa won by an innings (this was the match in which Hashim Amla made a mere 311 not out, in a huge partnership with Kallis).

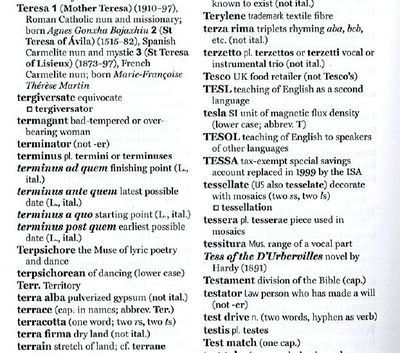

I was pleased at the time that the LRB saw fit to publish my silly letter but irritated at their lower-casing of the T of the word Test. Not even the Guardian which tends to lower-case most words, refers to “test” as opposed to Test matches. And as our style guide here, the New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors, makes clear, the T should be capped.

This is a small pedantic point perhaps, but I suspect some people have a problem with cricket, seeing it as part of some kind of post-imperialist hangover. It can be hard to keep politics and ideology out of cricket. Having said that, maybe at the TLS we err too much on the side of upper-casing words that no longer demand it, but we are slowly, inexorably, moving into the twenty-first century.

Meanwhile the name Jacques Kallis with its vaguely French inflections has always intrigued me. Jacques is pronounced with a long “a” (preferably in a South African accent). I’ve yet to read a biography of the cricketer so don’t know his family history much beyond the fact that he hails from Cape Town. But online researches did throw up the following (in response to someone as curious as I am):

“The first Kalis (or Kallis) to arrive in the Cape (from Hungary) was Joseph Kalis, b 1753, d 17 Apr 1859. He or his ancestors were French, named Berange, fled France and went via Poland where the name was changed, taken from the town Kalisz. Kallis appears to be one branch of the family, from about the 1870's, starting with the children of Joseph Gerrit Kalis.”

So there you have it: a champion Test cricketer with possible French roots. It doesn’t get much better than that.

January 1, 2014

Alexandria in paperback in The Guardian

On this day three years ago I was in Egypt, writing a diary that became Alexandria: The Last Nights of Cleopatra.

Today, when I am somewhere else writing something else, a handsome Granta paperback appears of this book - £9.99 and at only £7.99, I discover, at Watersones.

I enjoyed reading the reviews last year of the rather pricier hardback but there was a particular pleasure today to read in The Guardian Nicholas Lezard's Paperback of the Week.

I liked what he had to say but I also liked being reminded of New Year 2011 - and hoping that this quieter new year brings both good new words from me (every writer's hope) and new readers for the old.

December 31, 2013

Feasting with Dennis Wheatley

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's not what I'd imagined I'd be reading in Christmas week – the latest reissue of Dennis Wheatley's first novel, The Forbidden Territory, with this grinning Damien Hirst-a-like on the cover. It's turned out to be fairly suitable entertainment for the season, however, being a ripping yarn (first published in 1933) about a perilous rescue mission into unknown Soviet terrain, that also features plenty of outrageous feasting.

The tone is set from the start, with the Duke de Richleau, an "elderly French exile", sharing a post-prandial Hoyo de Monterrey cigar and a mysterious letter with his young Jewish friend Simon Aron. Next Simon finds himself enchanted by a Russian actress at a party in Hampstead; she consumes "two large plates of some incredible confection, the principal ingredient of which seemed to be cream, with the gusto of a wicked child" and knocks back champagne lashed with Benedictine.

The Hoyos follow our heroes to Moscow, where they are welcomed with some enthusiasm: "Simon . . . ran his fingers lovingly down the fine, dark oily surface of the cigars". The imported cigars, naturally enough, serve as a cover for a smuggled-in pistol. The disappointments of bad food are not allowed to pass without comment. Things get (gastronomically) rougher before they get better, but our heroes can still dream. "Wouldn't mind Ferraro showing me to a table at the Berkeley . . . just at the moment", Simon says, as they head into the frozen depths of the forbidden territory itself.

Such pleasures, Hoyos, mysteries and all, were to become common fare in this particular series of Wheatley books: following this extremely successful debut, he wrote a further ten novels starring Richleau and his associates. In the last one, Gateway to Hell (published in 1970 but set in the mid-1950s), they are still dining on "smoked cods' roe, beaten up with cream and served hot on toast, after being put under the grill, followed by a Bisque d'Homard fortified with sherry, a partridge apiece, stuffed with foie-gras, and an iced orange of very old Madeira" etc. As with James Bond's blow-outs, recently back in the news thanks to a full (and sobering) medical examination, the reader might at first envy all of this fantastic indulgence, before having second, more timid thoughts about its likely effect on the body. It's fortunate for the Duke, an old soldier, that he at least knows "the secret of certain exercises, which relaxed the muscles and relieved their strain" – one of the "many things about the human body" he learnt from a "Japanese manservant".

It's been said that Wheatley's secret agent Gregory Sallust provided Ian Fleming, his sometime colleague in the extraordinary Deception Planning operation during the Second World War, with a model for Bond. Here in Wheatley's first novel, however, a few years before Sallust came on the scene, that crucial motif of indulgence is already present, anticipating the Bond of Casino Royale (1952), Fleming's own first novel, in which the protagonist finds that the trouble is not "how to get enough caviar" but "how to get enough toast with it". Bond has other pleasures, of course, but lacks one that Wheatley gave to the Duke: an interest in literature.

Bond, in Andrew Lycett's words, "never reads much more than Scarne on Cards and the occasional thriller", something that sets him apart from Fleming himself, the founder of The Book Collector. Wheatley, by contrast, in this series at least, has the luxury of dividing the necessary heroic qualities between the Duke, Simon and their usefully burly American friend, Rex Van Ryn. On the Duke, Wheatley bestows, among other things, a magnificently adorned library: "The walls were lined shoulder-high with books, but above them hung lovely old colour-prints, and a number of priceless historical documents and maps". This might be a fantasy, but Wheatley himself, at his death, had accrued a collection of thousands of books that Blackwell's, in Oxford, deemed to be worth cataloguing and selling off. He inscribed a copy of The Forbidden Territory to the bookseller Percy Muir, "my old friend . . . who has put me on to many good books".

And on a long train journey, we are given a clue to the Duke's literary tastes: "They settled themselves comfortably on the wide seats, and the Duke took out Norman Douglas's South Wind, which he was reading for the fourth time". There is much more detail about Wheatley and his characters in Phil Baker's excellent biography, The Devil Is a Gentleman, but Wheatley himself has this much to say about South Wind in the second volume of his memoirs, Officer and Temporary Gentleman, 1914–1919: "This book is a riot of enjoyment for the conscious hedonist; for those who regard the Ten Commandments with indifference; for the truly intelligent who seek only beauty and happiness". These latter phrases don't fit squarely with De Richleau, I admit, but the first part would seem to describe an addict to Hoyos and fine dining pretty well. We usually find him dining in company, but it's easy to imagine him devouring a good book along with a good meal on his own.

The Forbidden Territory is one in an enjoyable trio of books to be reissued recently by Bloomsbury in paperback – while many of the many others have been made available as e-books. (Apparently, they've been edited, although it's not immediately clear what changes to the text, if any, that has entailed.) The other two, The Devil Rides Out and To the Devil, a Daughter come closer to the satanic stereotype for which Wheatley has remained famous, but represents another side of his work, pitching somewhere in the wide territory between Fleming and John Buchan. Its wary depictions of Soviet society are also noteworthy, although the anonymous TLS reviewer of 1933 thought the novel would have been better off set somewhere like Anthony Hope's Ruritania; although he "occasionally achieves accurate description of Soviet conditions", there are "obvious errors" of fact that the novel wouldn't otherwise draw attention to.

With regard to Wheatley's style, Ronald Hutton, in his TLS review of The Devil Is a Gentleman, seems to have hit the nail on the head. Although writing was Wheatley's "natural vocation", "In one sense, he did it badly":

"he could never spell properly, had a poor literary style and committed howlers. His editors weeded out most of these, but one story still made Copenhagen the capital of Sweden. What he provided were superb plots, designed to build and release tension expertly, in wave-like patterns. His characters, though stock, were vivid, the settings luxurious and the historical and cultural backgrounds usually carefully researched. He published on an industrial scale, completing two new books per year in the first half of his long career and one thereafter. His experience of business enabled him to excel at marketing them, and though they never earned him honours from the literary world or the nation, they did make him rich. Baker argues plausibly that, in his range of subjects and the associations that his name evoked, Wheatley was the greatest non-literary writer in twentieth-century Britain."

There were certainly awkward patches in my easy holiday reading: for instance, the bemusing scene in which a man in a mask that completely conceals his lips manages both to spit on the floor for dramatic effect and swallow his drink through a slit. It was interesting to discover, then, that Wheatley himself did not regard all his creations as equal. He agrees with the reviewer who says of The Fabulous Valley (one of several books published the year after The Forbidden Territory): "Mr Wheatley should make up his mind whether he is going to write a thriller or a guide-book", and judges Uncharted Seas to be "Not a patch on They Found Atlantis". The Forbidden Territory, however, is "much better" than Three Inquisitive People (an earlier effort not published until later).

This information about Wheatley's self-assessments comes from this website devoted to the author and his works; further examples, probably buried in unique book inscriptions, are sought. Also: any further examples of Wheatley's Christmas cards . . . .

December 27, 2013

Malcolm Bowie the critic

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In between the mince pies and rounds of charades I’ve been dipping into the Selected Essays of Malcolm Bowie. It’s proving a rewarding experience. Bowie (1943–2007) was one of the most penetrating and stylish critics the TLS had the good fortune to commission (and whom I never had the fortune to meet). One of his last essays for the paper was a characteristically generous and thoughtful review (July 26, 2002) of two massive biographies of Marcel Proust, one by the French scholar Jean-Yves Tadié, the other by the American William C. Carter. Here is its bracing opening paragraph:

“The narrator of Proust’s A la Recherche du temps perdu has many unkind words for self-proclaiming art lovers. And as he prepares to launch his own aesthetic manifesto in the final volume of the novel, his hostility to those he calls ‘les célibataires de l’art’ – art’s bachelors – acquires a new intensity. They are locked inside their admirations, and when they eventually do break out into speech they often merely exclaim and expostulate. They are like goslings who flap their infant wing-stumps in a ridiculous attempt at flight. Or rather, he adds, pressing home the insult and warming to his aeronautical theme, they are like those early flying machines that never left the ground. Critics are even worse, the narrator goes on to say, in that they combine docile adherence to fashion with a fondness for desiccated classificatory schemes, whereas the enthusiasts at least have the merit of an active appetite for artistic experience. Their oohs and aahs may even conceal a nascent idea or two.”

Bowie praises both biographies, while referring to them as “untouched by textual discussion” (Bowie was all about the text), and concludes “Finishing either of these thousand-page volumes will . . . leave readers hungry for the pleasures of Proust’s book. As we turn again the pages of the novel, the wit, malice and swagger that are so little present in the story of Proust’s life suddenly reacquire life of their own”.

This article is not included in Dreams of Knowledge, the first of two volumes of Bowie’s essays (published by the Oxford-based academic imprint Legenda). The two volumes will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS but I thought it worth while to draw attention to them here as these books will not be available in your local bookstore.

In her Editor’s Introduction, Bowie’s widow Alison Finch (herself a French specialist at Cambridge) gratifyingly suggests that his “relationship with the TLS was a productive one. He enjoyed ‘talking to’ its educated readership . . . . The reviews gave full scope for that quality which, in Proust, he describes as ‘intellectual gaiety’”.

As the second volume bears out, Bowie’s range was considerable: as well as the probing essays on French poets from Mallarmé to Francis Ponge and René Char, he wrote programme notes for opera productions at Covent Garden, reviewed Edward Said’s Musical Elaborations, while his last long piece for the TLS was an article on the German Lied. He was also excellent on film.

Among the essays on Proust in this volume (in “a wealth of material which will be new to almost all of his readers”) is the brilliant “Proust and Italian Painting”, which was first published in Comparative Criticism. (At this point I make no apology if a TLS blog should once again find its focus on Proust. as his anniversary year draws to a close.)

“Simplifying matters somewhat, we could say that, for Proust, Italian painting springs fully formed into life as Giotto paints the Scrovegni Chapel in the early fourteenth century and expires some two hundred and fifty years later during the old age of Titian. Baroque and eighteenth-century painting exist only fitfully in his compendious [good adjectival variant!] novel, and later Italian painting not at all.” How strangely useful it is to be told this.

Bowie discusses an episode in La Prisonnière in which Charlus takes his young lover the violinist Morel to a restaurant:

“I can’t go out with him to a restaurant without the waiter bringing him notes from at least three women. And always pretty women too. Not that it’s anything to be wondered at. I was looking at him only yesterday, and I can quite understand them. He’s become so beautiful, he looks like a sort of Bronzino; he’s really marvellous.” (C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation, revised by Terence Kilmartin and further revised by D. J. Enright)

“We could say that Bronzino appears here simply as shorthand for sexual ambiguity in males, and that the languid elaborations of the Mannerist style are being summoned up by Charlus for his familiar purpose of erotic provocation. He seems to know what Bronzino was at when he painted those beautiful feminized youths whose displaced virility is returned to them by a sword, an armoured codpiece, or a nearby marble figurine.” Bowie directs us to Bronzino’s “Portrait of a Sculptor” (in the Louvre, above). Brilliantly illuminating.

But then Italian painting has its more prosaic purposes for Proust’s characters: they “use paintings for their own worldly ends, handle them with carefree impropriety, and have only a fleeting sense of their independent aesthetic dignity. Proust’s novel is a disorderly imaginary museum in which no exhibit has a fixed position or a stable value. The Italian galleries of this museum have their own fluttering population of ghostly grandees, whether artists or sitters.”

December 20, 2013

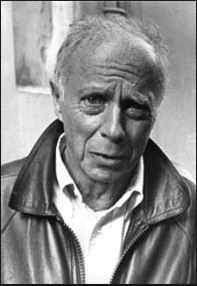

Claude Simon, George Orwell and Catalonia

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Before the year is out it would perhaps be right to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of Claude Simon (above, born on October 10, 1913). In the glut of Gallic anniversaries which I blogged about in October and November there was simply no room to fit him in. Simon, born a few weeks before Camus, considerably outlived him – he died in 2005. Like Camus he was awarded the Nobel Prize (1985). There the similarities end.

Camus’s work is well known but even in France Simon remains little read, being considered difficult. An early nouveau romancier, he only truly found his voice with La Route des Flandres, published in 1960 – the year in which Camus had his fatal car crash. The novel drew considerably on Simon’s disastrous experiences in the French cavalry in the spring of 1940, when the country was overrun in a matter of weeks.

Like an itch in continuous need of being scratched, the war was a theme he returned to repeatedly, notably in the triptych-like novel with the Virgilian title Les Géorgiques of 1981 – the artistic allusion is apt as Simon trained as a painter and was a great admirer of his near-contemporary, the Brut artist Jean Dubuffet.

The outer panels cover 1940 and the Revolutionary period in the shape of the career of an army officer who took part in the storming of the Bastille before retiring to the south-west of the country to tend his vineyards (Simon himself inherited a vineyard). The middle section focuses on a certain English writer identified as "O", and is, in the late Christopher Hitchens’s phrase, “an obsessive reworking of the action of Homage to Catalonia . . . “. In his Why Orwell Matters (2002), Hitchens took strong exception to the way Simon represented Orwell, attributing to him thoughts and sentiments he could not possibly have deduced.

In a (rare) interview to the Review of Contemporary Fiction (Spring 1985), Simon made the bizarre claim that Orwell’s account of the Spanish Civil War was “faked from the very first sentence”: “There is an element of fellow-feeling in my response to Orwell’s personality, and I have a profound admiration for his personal courage. I would unfortunately not be inclined to go so far regarding his intellectual courage and honesty. Without making too much of it, and mentioning only for the record his idyllic description of Barcelona in November 1936, which is little more than a comic tourist guide, I should point out to these same critics that Homage to Catalonia is a work (or rather a piece of special pleading on his own behalf) which is faked from the very first sentence: ‘In the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona, the day before I joined the militia,’ etc”.

The “faked” assertion drew particular scorn from Hitchens. It is a strange claim and one that Simon doesn’t explain satisfactorily. Maybe the interviewer should have pushed him further on it. Orwell himself was in no doubt about the difficulties he faced in reporting: “I have tried to write objectively about the Barcelona fighting, though obviously, no one can be completely objective on a question of this kind. One is practically obliged to take sides" (p153, Penguin edition).

Hitchens later writes “M. Simon had himself been in Spain, though fighting on the side of the Stalintern forces [an implied criticism – Simon was a member of the French Communist Party], and must at some point have believed that ‘History’ did indeed have a point and a direction, and was indeed on ‘his’ side”. Hitchens concludes, fiercely, “The award of the Nobel Prize to such a shady literary enterprise is a minor scandal, reflecting the intellectual rot which had been spread by pseudo-intellectuals”.

But it’s worth stressing that Simon’s portrait of Orwell is far from unsympathetic. He writes: “Having returned to the front line towards the end of May 1937 after a short leave and a winter spent in the trenches on the Aragon front, O . . . is hit during a tour of inspection of the forward outposts by a bullet which goes clean through his neck . . .” (this from the translation The Georgics by Beryl and John Fletcher). Later we read: “There will however be gaps in his story, things left unclear, even contradictions. Either because he takes certain things for granted (his past: the education he received in the aristocratic college of Eton . . .)” (Simon’s grasp of English was, I sense, shaky); and “On the one hand his upbringing (or his dignity – or his natural decency?) preserves him from all boastfulness . . .”.

And finally: “He (O.) also leaving behind him the accredited correspondents perched on their bar stools, busily writing for the organs of the liberal foreign press the articles which he was later to devour on his return with the dejected amazement, the dejected indignation that a survivor of a shipwreck would feel on reading in black and white that there had been neither storm nor shipwreck . . . ”.

Can this be the same Claude Simon that Hitchens viewed with such disdain?

Simon’s last full work, Le Tramway, was published in 2001. I reviewed it in the TLS, suggesting that it “displays all the qualities for which his writing has become celebrated [an exaggeration there surely]: the sweeping, endlessly ramifying clauses (with their parentheses within parentheses), intended to convey a constantly shifting pattern of thought and sensation; the almost photographic description and . . . powerful recourse to memory”. I also called it “a book drenched in the summer sun: the sights and smells of the Mediterranean . . . “. It’s certainly a long way from the polemics over accounts of the Spanish Civil War.

December 18, 2013

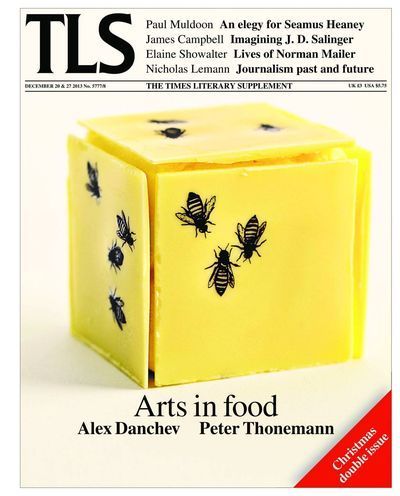

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

To those readers already sated with sugared platitudes of the season, this is a bracing, salted double edition of the TLS. James Campbell delivers a damning verdict on the new, much-publicized biography of J. D. Salinger, the official book of the little-acclaimed new film about the author of The Catcher in the Rye. Campbell detects two dominant theses, about war and sex, neither of which convince. He fails to detect an index to the 600 pages because, bizarrely for such a book, the publishers saw no need for one. Daniel Karlin has been considering another life of a legend, Ian Bell’s massive work on Bob Dylan, in which the early period comes with not a single new fact or forgotten witness, and the rest is resonant (very slightly) with “summary lessons on major events”. Neither Gandhi nor his latest biographer emerge well from R. W. Johnson’s review of the Mahatma’s life in South Africa before 1914: Ramachandra Guha’s account, however, is “suffused with a sort of euphoric glow from the Gandhi-yet-to-come era in India”. Michael Dirda, formerly of the former Washington Post Book World, recounts his memories of Christmas times gone by, when books were bought, rated in lists, but not very much read.

The TLS does turn out to have one set of holiday heroes this year, the bakers of cakes based on modern works of art, like the Richard Avedon parfait of bees which graces our cover. And there is credit too for the cooks of the Soviet Union, those inventive mistresses of the arts of Stalinist cod and processed cheese. Lesley Chamberlain praises a memoir by Anya von Bremzen that offers nostalgia, tragedy and “absurdity by the ladleful”.

Finally, for all those anxious about the future of all newspapers this festive tide, Nicholas Lemann salutes George Brock’s Out of Print, which “deals comprehensively, intelligently and unsentimentally with the entire range of major questions about journalism now”. Brock’s book is the “best single source available for wisdom and context about the situation as a whole”, a verdict which sounds like a recommendation for the Christmas trade but might be better kept for when reality and reading return in the New Year.

Peter Stothard

December 17, 2013

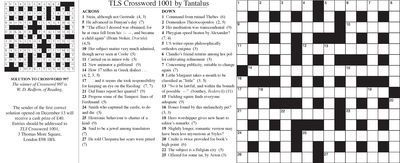

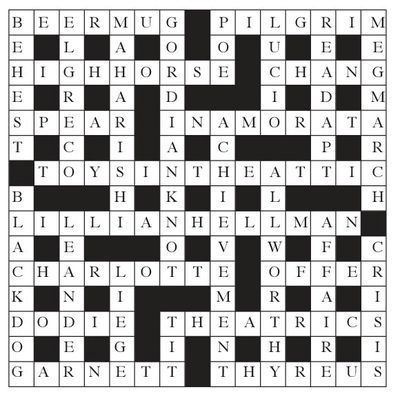

1,000 TLS crosswords and counting

By MICHAEL CAINES

TLS subscribers will already know that there's one part of the paper that recently reached a significant milestone: the crossword. The 1,000th puzzle appeared last month and, as was noted in the paper at the time, most of this grand total is the work of one man, "Tantalus", "periodically revealed to be Don Yerrill of Dumfries".

It's only recently, however, and most unusually, that I had the chance to appreciate once again what an intricate and particular skill setting such a puzzle is, as, in one of ad hoc situations that sometimes affect a busy office, I had to prepare this week's crossword (1,005) and the solution to 1,001 for going to press. Apologies in advance to any puzzle addicts who find that 1 Across won't be made to tally with 4 Down – blame the stand-in (me), not Mr Yerrill.

At least that gave me the chance to mark that milestone by putting 1,001 online, above (click on it to see the the thing at a more legible size), and its solution (below) on the TLS blog. And if you don't speak the cryptic crossword language, this example may give you some sense of how the game works, and why some people become lifelong addicts.

The basic secret is: the quotations with missing words aside, there are two parts, or a double meaning if you prefer, in every clue, one reinforcing the other, and in the particular case of the TLS Crossword, there's usually (but not always) a literary slant to the answer. "Charlotte", for instance, is the solution to 21 Across, which innocently asks "Did Bates report her quarrel?" (9). The double meaning lies in the last word: in Charlotte's Row, Bates (H. E.) was referring to a row of Midlands houses, rather than any other kind of "row".

There's more thorough guidance and enlightenment on the long history of the crossword – which apparently turns 100 on December 21 – in the recently published Two Girls, One on Each Knee (7) by Alan Connor. This book shows you, among other things, how speaking aloud unpromising phrases such as "Tooting Carmen" and "Servant Tease" can yield obvious answers, and how sociable the crossword is. Of course, it can be tackled alone, and in Brief Encounter, it represents the antithesis of the longed-for romance, but it's also perhaps fun to tackle with two or more heads rather than one. "Crosswords bind families", Connor argues, through the "exchange of texts between geographically distant siblings that accompanies their regular appointment with a Saturday prize puzzle, or the extended clan attempting a group-solve of a Christmas jumbo over those post-Christmas Day days . . .".

In the end, the "social angle" wins out over the old canard about cryptic crosswords being both the preserve of the particularly intelligent and a charm to keep the mind healthy and memory-sharp in old age. Experience, it would seem is more important than intelligence (some setters and puzzlers like to return to the same clues and/or answers, seeing them as "old friends"), and the crosswords-versus-dementia story is popular with newspapers but scientifically unproven. I'd also like to think that the fun doesn't lie purely in the satisfaction of filling the grid, but bashing your brains against each separate, sometimes ludicrous little phrase. "US writer opens philosophically orthodox enigma" (3). What can it all mean?

December 12, 2013

Undigitized and unknown

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Two pieces in the TLS this year – one by A. S. G Edwards and the other by William Proctor Williams – have warned of the dangers associated with the digitization of books and manuscripts. But a recent exhibition at Senate House, organized by Cynthia Johnston of the Institute for English Studies, provided some striking examples (see some of them above and below) of the sorts of items that can languish unnoticed without its help.

Little attention has so far been paid to the fabulous collection of manuscripts, incunables and early printed books bequeathed in 1946 by R. E. Hart (a member of a philanthropic rope-manufacturing dynasty) to Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery – for the simple reason that few people are aware of its existence. When Johnston visited recently she was told that there had been three academic visitors in five years.

Johnston has called the Hart collection “just one example, although a rather fine one, of underfunded collections marooned by the gap between digital access and vanished funding”; she hopes that the money will, at some stage, be raised to get all Hart’s books online. How else can the museum stimulate international interest in a resource deemed by Johnston to be of “major importance to the study of bibliography, art and social history”?

(The following information is taken from the exhibition catalogue, edited by Johnston and Sarah J. Biggs, 978 0 9927257 0 9.)

Above: A page from the Peckover Psalter; France (Paris or eastern France?), c.1220–40. This is “one of the gems of the Hart collection”, a "lavish production of scholarly devotion and artistic skill". It contains ten miniatures showing scenes from the life of Christ painted against a vivid gold background, and two scenes of King David. Here he is shown playing the harp and (underneath) as a young man confronting Goliath.

Top: Book of Hours, Use of Rome; Northern Italy (probably Venice), c.1470-80. This Book of Hours contains sixteen large historiated initials and eleven full-page miniatures, including this arresting one in the tradition of memento mori.

Above: Book of Hours, Use of Sarum; England, c.1420–30. The historiated initials and complex borders show the influence of Hermann Scheere, whose work is found in some of the most luxurious manuscripts produced in London during the first quarter of the fifteenth century.

Book of Hours, Use of Sarum; England, c.1440. This English Book of Hours contains “not only a beautiful programme of illumination but also remarkable evidence of the aristocratic families that once owned and cherished it . . . . The workshop responsible for its illumination succeeded in creating a unique synthesis of English figural scenes with Flemish-style borders”. This synthesis can be observed in the Annunciation miniature above.

Above: Ars Moriendi; printed by Konrad Kachelofen at Leipzig, c.1495. Ars Moriendi was a popular fifteenth-century guide to dying well: “After conquering a series of spiritual temptations presented by a host of devils, Moriens, the dying man, triumphs over unbelief, despair, impatience, spiritual pride and avarice and is ultimately rewarded by salvation”. This volume is an example of the rarer, shorter version of the Ars Moriendi, which may have been intended for the semi-literate as well as the literate.

Above: Bernard von Breydenbach, Peregrinationes in Terram Sanctam; printed by Peter Drach, Speier, Germany, July 29, 1490. Peregrinationes in Terram Sanctam, first published in 1486, is an account of the nobleman Bernard von Breydenbach’s journey to the Holy Land in 1473. It became one of the best-selling books of its time. Part of its success came thanks to the illustrations by Erhard Reuwick, “the first such to be printed in any account of this kind. Places like Venice, Paris and Rhodes are shown in extraordinary detail, offering us vibrant glimpses of these towns in the late 15th century”. Reuwich’s panorama of Jerusalem is spread across six pages (this copy lacks two of them) centred on the Temple Mount.

December 11, 2013

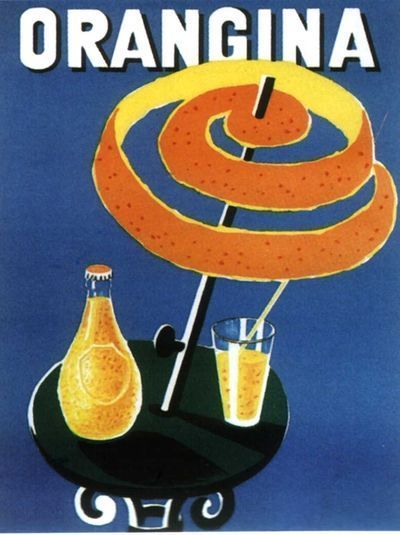

Orangina naturellement

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Coca-Cola may be the king of fizzy drinks but Orangina gives it a good run for its money in France. The distinctively flavoured (orange and citrus) liquid in its distinctive 250 cl bulbous-shaped bottle with a pitted surface to evoke the texture of orange peel was first successfully marketed in France shortly after the war, by Jean-Claude Beton, who has died aged 88. The formula for its content was invented in the 1930s by a Spanish pharmacist called Agustin Trigo, who called it Naranjina. Beton’s father Léon Beton was taken with it and sold it in Algeria in the 1930s as Orangina.

After the war, Jean-Claude Beton set up production in an old distillery in Boufarik in Algeria and devised the famous bottle. French soldiers returning from Algeria were advocates. It wasn’t long before it was being sold and then produced in Metropolitan France. Beton called it “the champagne of soft drinks”. The famous logo, meanwhile, was introduced in 1962.

Orangina was first sold in the United States in 1983 and the UK in 1985 ("Shake it and wake it!"). But the stuff sold mostly in 500 cl plastic bottles over here doesn’t seem to have the intensity or quite the taste of the original – and no pith. In 2008, meanwhile, a TV advertising campaign for the drink was criticized for its sexualized depiction of anthropomorphic animals when it was shown in Britain. Looking at it again, it does strike me as a bit silly but fairly inoffensive.

Orangina has always seemed as quintessentially French as Perrier, Pernod Ricard and Dubonnet (does anyone recall the advertising slogan “Dubo . . . Dubon . . . Dubonnet”?) To me as a child on family trips across France, it represented a reward for agreeing to be shown yet another flying buttress on a Gothic cathedral. I probably consumed it on a café terrace in sight of the cathedral boasting those flying buttresses.

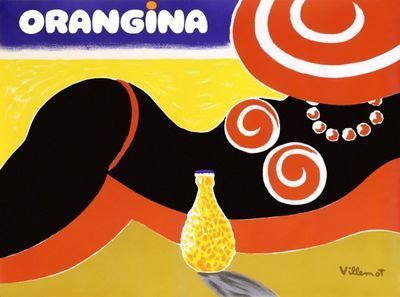

I don’t recall whether Orangina was advertised on the sides of buildings in towns in the north of the country in the way that Dubonnet was – those peeling billboards vying with electioneering posters for Jacques Chaban-Delmas or Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. It was probably a southern thing. It certainly evoked the sun of the South (as in Bernard Villemot's publicity poster, below).

Maybe one day I’ll blog a paean of praise to that other French design classic: Kronenbourg 1664.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers