Peter Stothard's Blog, page 51

November 27, 2013

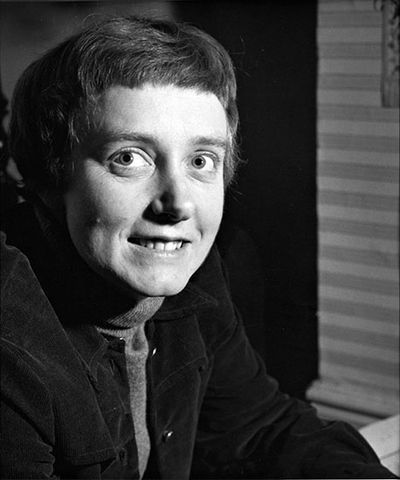

Maureen Duffy at 80

© John Vickers/University of Bristol/ArenaPAL/TopFoto

By MICHAEL CAINES

I'd like to know if this happens often: a writer in her eightieth year publishes two books, all but simultaneously (OK, within months of one another); one of those books is in prose and the other is in verse.

It might sound like the classic Dr Johnson type of praise – ie, we're not impressed by how well it's done, like the dog's walking on its hind legs, but that it's done at all – but I think it's notable for other reasons, too. For one thing, in the case of the formidably versatile Maureen Duffy, it's possible to say that the publication this year of a poetry collection, Environmental Studies, and a novel, In Times Like These, keeps up a seemingly lifelong commitment to working in these two forms. (That's How It Was, her highly praised first novel, appeared in 1962, while her Collected Poems is dated 1949–84.)

And then there's the work for performance, the campaigning for Public Lending Right and – not least with The Ballad of the Blasphemy Trial, prompted by a case against the Gay Times – in opposition to homophobia and its various mechanisms of control. How do writers like her and Brian Aldiss do it?

Duffy also wrote a biography of Aphra Behn, which is why, when you search for her in the TLS archives, one of the things that appears under her name is a review of all but simultaneous (OK, within hours of one another) revivals of two of Behn's comedies:

"It is, I suppose, one of life's little ironies", Duffy wrote in 1984, in a review of The Rover (at the Upstream Theatre, if you remember that) and The Lucky Chance (at the Royal Court), "that after more than 200 years of neglect and vilification two plays by Aphra Behn should have opened in London within a night of each other . . . ."

There's also, incidentally, in a review of one of Duffy's novels of the 1960s, a nice reference to her "staying-power" . . . .

I'm hoping to attend the day of celebration for this author's own brace of poetry and prose publications at King's College London, on December 6, Maureen Duffy at 80, which promises contributions from both novelists (Ali Smith, Maggie Gee) and poets (Alan Brownjohn, Elaine Feinstein, Ruth Fainlight et al). If nobody else asks, I'd like to know: is there simply a switch in the minds of certain writers that enables them to switch from metred to un-metred and back again?

November 25, 2013

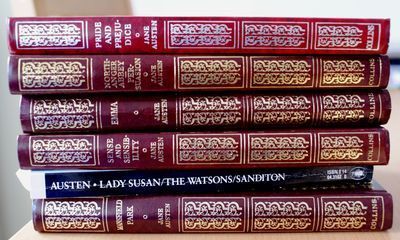

How many great novels did Jane Austen write? And other notes from Austenland

By MICHAEL CAINES

A performance, a panel discussion and a movie are what Bristolian Jane Austen fans can expect tomorrow night, courtesy of the Bristol Women's Literature Festival. To celebrate "The Glory of Pride and Prejudice" together, all they need to converge on the Watershed, where they can enjoy a performance by Kim Hicks, a discussion involving two professors, the author of Who Needs Mr Darcy? and a young Austen fan, and a screening of Joe Wright's film version of 2005. That's surely plenty to be getting on with.

And yet, for the person truly in the grip of Austen-mania, maybe not. You could spend the next few months traversing the South of England, from Bristol tomorrow night to the museum in Chawton, Hampshire, digressing to London for a spot of Austen-based improvization or (early next year) a Mansfield Park study day. By all means, venture up north for Jane Austen's Regency Christmas festival or Jane Austen's Christmas concert – just be home in time for the BBC's adaptation of Death Comes to Pemberley, won't you? You've just missed the Jane Austen Celebration Day in Lymm, but never fear; something tells me there's bound to be another excuse for celebrating Jane's fame soon.

Here's one that I'll mention as a slightly less curmudgeonly NB to my post about the Georgians (of which a proper TLS review, not by me, is coming soon): one neat touch is that the BL exhibition's copy of Cecilia by F. Burney is open at the page where one female novelist seems to have inspired the other:

"The whole of this unfortunate business", said Dr Lyster, "has been the result of PRIDE and PREJUDICE. . . . Yet this, however, to remember; if to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you owe your miseries, so wonderfully is good and evil balanced, that to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you will also owe their termination . . . ."

So now any visitor to the BL this winter doesn't even need to call up a copy of Cecilia in the rare books room to see those words jumping up and down on the page, as they would have done in the mind of the author of "First Impressions", crying out to be stamped on a title page.

The world is always interested in Jane Austen, as another professor put it in the TLS earlier this year – hence the concerts, the films, the films of genre-twisting sequels to the novels. And I'd fondly imagined that the basis of this phenomenon was a widespread admiration for six novels by a single, ingenious hand. (Unless Austen was ambidextrous.) You'll remember the one about the philosopher who was asked if he read novels, and said yes, I re-read all six every year . . . . Only now I know that he/I/we got the most basic thing of all wrong: the adding up.

It’s not the done thing to pick on a press release – although unfortunately it tends to be the impressively poor ones that sometimes stick in the mind, either for their magnificent prose or for getting something completely wrong about the book they're trying to promote – but there's something striking about the first line of the salmon-pink sheet that accompanies Penguin’s latest reissue of the Complete Novels of Jane Austen:

“Enduringly popular, treasured and enjoyed, the seven great novels of Jane Austen, beautifully repackaged in a new hardback edition”

The seven great novels? This isn’t a claim you’ll find on the dust-jacket of the collection itself, also salmon-pink, which instead features this piece of praise from Nigella Lawson:

“Tells us wisely and wittily about the nature of romantic entanglements and the follies of being human”

The grammatical incompleteness gives the game away: it is Persuasion that Ms Lawson is singling out here, rather than Austen’s oeuvre as a whole. She places it above the others, in fact: “Everyone has their Austen, and this is mine”.

The seventh novel turns out to be “Lady Susan”, the short epistolary fiction that is more usually packaged with the incomplete works, “The Watsons” and “Sanditon”, and regarded by some as mere apprentice work, handy principally for the speculations it might provoke about the major ones. So my initial thought was that only somebody trying to sell the Complete Novels both accurately (it contains seven novels) and hard (they're great!) would try to pass off "Lady Susan" as "great". I hadn't read it for years but, actually, enjoyed it very much this time round. Then I wondered what the critics say. Many of them ignore it entirely. But those who don't necessarily dismiss it out of hand.

Of those three minor works (the other two being unfinished), for example, Margaret Drabble, calls "Lady Susan" the "earliest and possibly the least satisfactory" ("What a pity it is that she never, in her mature work, returned to the subject of a handsome thirty-five-year-old widow"). Janet Todd gives it a little more credit, in the Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen; Paula Byrne regards it as one of Austen's "experiments with narrative voice", "an important transitional work"; and Claire Tomalin imagines it could have been a better book "if its heroine were provided with an opponent worthy of her skills", but finds it "truly remarkable", all the same, for its "energy and assurance in trying out such an idea and such a character". Elizabeth Jenkins, many years ago, said:

"it contains no one character of such charm and worth that we long to read the remainder of his history; but as it stands it is a remarkable structure, comprising, within a very little space, a great deal of light and shade, and that most satisfying kind of excitement which is produced in the reader by turns of action at once dramatic and inevitable."

That doesn't sound so bad now, does it? Only don't hold your breath for a Christmas special.

November 22, 2013

Brésil! Brésil! Brésil!

Photo: AFP

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Against the odds, the French football team have qualified for the World Cup finals, to be played in Brazil next year. Condemned to the play-offs (les barrages), France were drawn against Ukraine and lost the first leg 2-0 in Kiev. No team had ever overturned such a deficit in play-offs for the World Cup finals. But France won 3-0 in Paris on Tuesday night. Having overcome their “barrage contre l’Atlantique”, to paraphrase a book title by Marguerite Duras, the team can book their tickets to Rio, as we football pundits like to say. Poor Ukraine. They must have thought they had it in the bag.

France are coached by Didier Deschamps, who was captain of the team when they unexpectedly beat Brazil 3-0 to lift the trophy (as we also like to say) in Paris in 1998: hosts and winners, France joined the one-time winners club, which includes England (will they ever add to that one triumph?) and, the most recent member, Spain, who won in the snoozefest in South Africa in 2010. (World Cup tournaments can be very boring indeed.) The elite teams are Brazil (5 times winners), Italy (4), Germany (3) and Argentina and Uruguay (2 each).

“Black-blanc-beur”, a variant on the “Bleu-blanc-rouge” of the French flag, became the popular slogan attached to the victorious 1998 team, made up of white players (Deschamps and a few others), black players (including Patrick Vieira, who was born in Senegal) and players of North African origin (a beur being a second-generation North African living in France), exemplified by the peerless Zinédine Zidane. Jacques Chirac, the conservative president, and Lionel Jospin, the socialist prime minister, attended the final of course, and subsequently hit record levels of popularity in the polls. France was looking forward to a great harmonious future, newly at ease in its multi-ethnicity and multiculturalism.

But that future hasn’t really come to pass. It was too much to hope for. In the intervening years, there have been riots in la banlieue – that untranslatable term denoting satellite towns of grim tower blocks on the outskirts of the cities. In response Nicolas Sarkozy, as Interior Minister in October 2005, suggested the “racaille” (scum) should be hosed down with water jets (he later claimed he was borrowing the term from an aggrieved resident, but it did no harm to his presidential prospects as it turned out). More recently there were the terrible events in Toulouse in March 2012 when 23-year-old Mohammed Merah went on a shooting rampage, targeting French Muslim soldiers and Jewish primary schoolchildren – 7 people were killed including three children – before Merah was himself killed during a siege. Meanwhile Marseille, France’s second city, has seen a spate of gangland killings over the past few months. And it seems as though every professional sector has taken to the streets in protest at one time or another over recent years, while there have been bizarrely vocal demonstrations against gay marriage. Unemployment remains at levels that wouldn’t be socially acceptable in Britain and standards of living decline.

And then there’s the racism, which has always been brazenly expressed in France. The black Justice Minister Christiane Taubira (who was born in French Guiana) recently endured racial insults of a kind that have been heard recently in largely mono-ethnic Italy but that one wouldn’t expect to hear in France. Her boss, President François Hollande, was slow to condemn the comments – in general, apart from his surprisingly bold and rapid intervention early on in Mali, Hollande has performed rather sluggishly (his popularity ratings are very poor). He must already be feeling the breath down his neck of the young and hugely ambitious Socialist Interior Minister Manuel Valls, who has spoken of the Roma population’s “inability to integrate” – an unexpectedly hardline stance from a left-leaning French politician. Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right Front National (and daughter of its founder Jean-Marie Le Pen), is gathering alarming political momentum: her party stands to do very well at next year’s European elections.

In 2011 Morgan Sportès, who was born in Algiers in 1947 and whose work caught the eye of the late Claude Lévi-Strauss, published a novel called Tout, tout de suite (Fayard) that seemed to capture something of the malaise in French society. His book is rather dramatically precised on the back cover: “Abandon all hope, you who enter here. This book is an autopsy: that of our society in the grip of barbarism”. It’s not clear how one novel can be expected to do so much, but it does reconstruct a real-life event: in January 2006, Ilan Halimi, a 23-year-old Jewish man of Moroccan extraction who worked in a mobile phone store in Paris was lured into a honey trap, tortured and murdered three weeks later. All the while his abductors, a large gang of black and Muslim youths known as “the Barbarians”, with strong anti-Semitic inclinations and a sense that young Jewish men were bound to have money, were in contact with Halimi’s family, demanding a ransom of €500,000 that they were unable to meet.

Sportès’s book is grimly readable: well researched, gripping and not a little shocking to those of us who find this world of depraved criminality alien. The dialogue is excellent and throws up such terms as “From”, “diminutif de ‘fromage’, c’est-à-dire un Blanc, un Gaulois”, “Feujs”, a pejorative term for Jews, and “keuf”, a cop. A “meuf” meanwhile is a "bint" .

In a front-page editorial in Le Monde last Saturday, we were told that the “for fifteen years, the performance of our football team has faithfully reflected the state of the nation”, and that since those heady days, “the collapse of the team has seemed like a cruel metaphor for the fate of the country”. (At its nadir the team refused to train during the finals in South Africa in 2010 and one of the players, Nicolas Anelka, is said to have turned the dressing room air blue in a confrontation with the hapless manager Raymond Domenech.) The editorialist blames this decline on unmerited huge salaries, large egos with little achievement to back them up, lack of national pride, this last perceived fault a gift to Marine Le Pen who is already complaining of too many foreign players in the French leagues (for “foreign” read African).

But the team have turned things on their head with what was by all accounts a very impressive win on Tuesday: so much for lack of pride in the French flag. The societal problems Le Monde alluded to remain. But the football team will after all be playing in the finals in the spiritual home of o jogo bonito. As the radio commentator screamed at the final whistle, “Brésil! Brésil! Brésil!”

November 21, 2013

The wee malt

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

The poetry pamphlet is thriving. Fears about digital poetry killing off print editions are, for the moment, happily unfounded. On Tuesday night at the Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets, now in its fifth year, poets and small presses were celebrated for their inventive, high quality contributions to, and ambitions for, this traditional art form, described by Marina, Lady Marks, whose late husband founded the prize and who continues generously to support it, during the welcome speech as “a complete and total expression of the universe” in up to thirty-six pages.

When the writer Jackie Kay judged the inaugural awards in 2009, she said of pamphlets, “their very smallness [makes] them feel special. There’s a great value, particularly in today’s world of blurb, blog and baloney, in keeping things brief. The pamphlet marks a new poet’s potential in a rather dignified way. It’s the wee malt as opposed to the big pint”.

Pamphlets, or “chapbooks”, are one of the first and, arguably, best places readers can encounter poetry and discover new and established poets. What is most interesting – particularly to this year’s judges, Tanya Kirk (lead curator of Printed Literary Sources at the British Library), Judy Brown (poet-in-residence at the Wordsworth Trust) and our own Thea Lenarduzzi (of the TLS) – are the different ways poets and publishers interact with the form. Tony Frazer of Shearsman Books, one of the shortlisted publishers, spoke on Tuesday evening about how pamphlets offer what books do not: for example, The Sun-Artist by Susan Connolly, which Shearsman published this year, consists entirely of visual poetry; and pamphlets can accommodate “long pieces that over-tip a conventional book layout”.

Flarestack Press received the award for Best Publisher because of their impressive local outreach. They support local poets and this year collaborated with illustration students from Birmingham Institute of Art, leading to pamphlets filled with sympathetic typography and design.

And then we moved on to the prize for Best Poet. Kim Lasky, who was nominated for her collection Petrol, Cyan, Electric, gave a serene reading of her science-inspired “Newton Sees the Seventh Colour”. Her precise writing style eloquently reflected (and refracted) the character of Newton, sitting at his desk: “you barely flinch, intent on experiment”. The best line, “as if rainbows were simply mathematics”, neatly applies to the unfathomable/fathomable process of writing, reading and understanding poetry.

Kim Moore’s nominated pamphlet, If We Could Speak Like Wolves, according to the judges “displayed with total assurance how ordinary settings hide the mysterious, bizarre and sometimes frightening”. After a five-hour train journey from Cumbria to the ceremony at the British Library, Moore was prompted to read her poem about a trip from Barrow to Sheffield. Witty observations of the train carriage (the twenty-five-year-olds on their phones talking about their fears of dying; chewing gum stuck on the table; and loos that will never smell fresh) ended with the image of a man dribbling on the speaker’s shoulder suddenly waking up with the rattle of a drinks trolley, shouting “I’ve got to find the sword”.

Neil Rollinson’s collection of monologues, Talking Dead, was wonderfully original. In it, first-person narrators chillingly speak of their, often violent, deaths – though Rollinson assured us that “it’s not a dark book, it’s a hopeful book”. In “A National Razor” (what the French call the guillotine), the poem’s persona feels the “lip of the blade” and hears the “innocent wood” groan. The chop is followed with more bizarre imagery, the speaker’s head lolling in a wicker basket: “I felt the blood run down my chin” and a man “put his fingers through my hair”.

The winning poet, David Clarke, was chosen for his “dark, political brooding”. “He takes risks and pulls them off”, said Thea Lenarduzzi. As Andrew McCulloch observes in his article (printed in this week’s TLS) about this year's pamphlets, “Clarke’s unflinching engagement with all that is fraudulent, artificial and cheap is backlit by a fundamental humanity”. Inspired by his adolescent obsession with the singer Edith Piaf, Clarke’s reading of “My Night with Edith” reminded me of Jonathan Swift’s excremental poems, with its image of a woman, whose name the speaker can’t quite remember, unfastening her stockings, “ripped off your sling-backs”, “your phony wig”, “your threadbare accent”. Unlike Swift’s personas though, the speaker here had “no regrets”.

November 19, 2013

Filling voids

By TOBY LICHTIG

Saudi Wahhabism and Haredi Judaism are not natural bedfellows, but the two cultures have a great deal in common: ancient traditions, conservative values, a literalist approach to scripture, a preoccupation with what women (and men) should and shouldn't wear (and eat and drink and enjoy), who they should and shouldn't fraternize with and marry. Two recent films have explored these notoriously insular communities with fascinating results – particularly when compared.

Earlier this year, I reviewed Haifaa al-Mansour's Wadjda (the first feature film to be shot entirely in Saudi Arabia), starring a ten-year-old girl whose pursuit of a bicycle (a forbidden symbol of freedom) is played out against the wider story of her parents' marriage – its monogamy under threat following the revelation that the wife can no longer bear children. The film is affectionate about Saudi life while remaining resolutely feminist: a tricky balance in a culture that makes such a daily drama out of subjugating women.

More recently, at this month's UK Jewish Film Festival, I went to see Fill the Void, which recalls Wadjda in both style and theme. Firstly, the look of Rama Burshstein's film is very similar, being made up largely of interiors within a single home. When the camera creeps into the outside world, the effect is jarring. In Wadjda, Riyadh is bathed in dazzling light; in Fill the Void, Tel Aviv seems bizarrely otherworldly in its familiarity. Ordinary teenagers skulk at bus stops and listen to their iPods – a world away from the intimations of eighteenth-century Poland (albeit in a comfortably modernized incarnation) seen behind the closed doors of the Haredi family home. Here, the men, viewed at various gatherings and festivals (most memorably a bibulous Purim celebration), resolutely club together; so do the women, gossiping in the kitchen, preparing food, clucking around the children. This isn't to say that that there isn't overlap – but it is noticeable in both films quite how much people rely on members of their own sex.

Fill the Void (which originally came out last year in Israel as Lemale et Ha'halal) also centres on a proposed marriage considered necessary to the community, if not by the bride-to-be. The film stars Hadas Yaron as Shira, who is encouraged to marry her sister's husband (Yochay; played by Yiftach Klein) after his wife dies in childbirth (the baby survives). There is no question that Yochay must remarry (a man cannot bring up a child alone, perish the thought) and it is deemed expedient to keep Yochay and the infant within the family (there is talk of an alternative match for the widower in far-off Antwerp). Despite her reluctance, Shira is gradually pressured into the marriage by her mother and the local shadchan (matchmaker) – although not by her sympathetic father – the narrative following the twists and turns of her difficult decision as she finds herself caught between social mores and personal volition.

Like the family in Wadjda, Shira's home environment is loving and relatively liberal. The portrayal is warm – but also subtly subversive. It ends ambiguously, on Shira's wedding day, with the young bride half-terrified as she prepares to undress before her husband (Shira is eighteen; Yochay a decade older).

Both films are very good at investigating the control of female bodies in strict religious households, where marriage is considered to be a matter for the whole community – a public event from inception to consummation and beyond. In both, it is the interfering women (mothers and mothers-in-law) who perpetuate this control over other women. The men, by contrast, are portrayed as mild, almost feckless. If women are to have a chance of throwing off the shackles, we are shown, other women will need to take the lead. It is in their very gentleness, their empathy, that both films explore this entirely logical message – one that in its context comes across as little less than radical.

November 18, 2013

The export of Gemütlichkeit

By MAREN MEINHARDT

A few years ago (three, to be exact), we carried a review of a book on the cultural history of the German Christmas. Rebecca K. Morrison, our reviewer, reported how all the things we associate with a traditional German Christmas, rooted in ancient tradition, are actually nothing of the sort: “Roast goose and red cabbage, bratwurst, gingerbread, candles, hand-crafted wooden figures from the Erzgebirge, blown-glass baubles for the Christmas tree, The Nutcracker and ‘Silent Night’" – all of this hasn’t been here for ever, argued Joe Perry, the author of Christmas in Germany.

Instead, according to him, the German Christmas is “a relatively recent invention, one moulded and manipulated by those in power from the early nineteenth century through the fractured society of the 1848 revolutions, the Franco-Prussian war, the unified Germany of the 1870s, two World Wars, the sandwiched Weimar Republic, the Cold War with US care packages – ‘the oranges, fine chocolates, coffee, soap, and perfume ... smelled like the West - and the Red Christmases of the GDR.”

But it’s an invention that exported remarkably well, from the first Christmas tree that Prince Albert introduced in 1840 and installed in Windsor Castle, to the German Christmas Markets that have sprung up all over the country.

So when the German Christmas Market, which has established itself as a recent tradition on the Southbank, was officially opened last Friday, what was needed of course was a German choir. And what better to lend the market authenticity than the Islington Meistersingers, the choir of the German Saturday School in Islington?

Authenticity, of course, is no less contestable a concept than tradition. A Christmas market in Germany is a finely calibrated thing. Several, ideally all, of the following conditions ought to be fulfilled: temperatures should be bitter, music preferably provided by things like bell chimes, and the drink is mulled wine. Focus is on tradition and local craft. The latter accounts for the continued popularity of the aforementioned carved wooden figures from the Erz Mountains, which, under normal circumstances, should constitute a niche taste, at best.

Since the notion of being rooted in local tradition is so crucial, this makes the idea of transplanting a German Christmas market to London a challenging enterprise. What, at any rate, should a traditional London Christmas market look like? I picture holly, ivy, some assorted pantomime villains, and perhaps a huge re-enactment of my favourite British Christmas tradition, the office party, so unlike the quiet and contemplative way things are done in Germany, and find that I am rather liking the idea.

But no matter. We are off to our rendezvous, the moose hut, and the common denominator of both traditions, the mulled wine – we are to be paid for our contribution in kind. Moose heads, incidentally, I can’t help noticing, tend not to manifest on Christmas stall fronts in Germany, or they didn’t when I last looked, admittedly a few years back. And what sort of a tradition do they stem from, anyway?

All of a sudden there is a hand on my shoulder. A huge Santa is has appeared somehow and now has thrown an arm around me and another around my neighbour. The neighbour, a tenor, is not a small man himself, but is positively dwarfed by the Santa. I can’t shake off the feeling that something about his face seems familiar, but cannot put my finger on it. He is loud, talkative and very jolly indeed. City Hall is not that far off -- surely it cannot be Boris Johnson?

Non-Boris then further unsettles us by seemingly throwing into question our status as genuine Londoners: “Are you local?”. I shift my attention momentarily from the music, to reply, a tad defensively, “Harringay, and how about yourself?” “North Pole”, booms the Santa, and I promptly miss my cue.

We get through our repertoire, before collapsing into the safe haven of “Stille Nacht” (without, we hope, any of the "sombre echoes" Rebecca K. Morrison detects), the Santa standing behind us all the while, directing enthusiastically. Three people clap, one of them Cathrin, the Director of the German school and our only fan. And we have started an Anglo-German Christmas tradition all of our own.

November 15, 2013

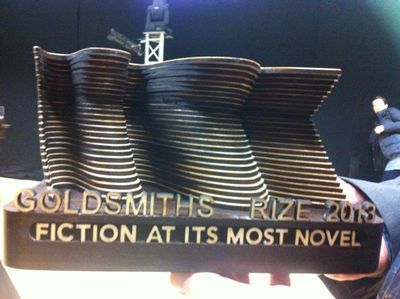

The Goldsmiths Prize: A rizing star

by TOBY LICHTIG

It is often tempting to carp about the hype of literary awards. I’ve done as much myself. But there was something genuinely exciting about Wednesday night’s Goldsmiths Prize.

The award was set up earlier this year to “celebrate fiction that breaks the mould and opens up new possibilities for the novel form”, and its four judges – Jonathan Derbyshire, Gabriel Josipovici, Nicola Barker and Tim Parnell (who chaired) – selected a genuinely intriguing shortlist, bursting with innovation, individuality and fresh ideas about the possibilities for fiction.

Jim Crace may have spent a career forging a now-familiar style, but in nominating Harvest, the judges reminded us that the author’s approach to writing novels is both stylistically and thematically radical, from his distinctive, rhythmic, iambic prose to his use of history to reflect on contemporary politics: both aspects combining in an ethics of fabular storytelling.

Lars Iyer, who was nominated for Exodus – the third instalment in his comic trilogy of anti-philistine novels – has been redefining the existential anti-hero for several years now, combining fiction and philosophy with great wit and invention. Ali Smith is one of Britain’s most interesting novelists and Artful is another blend of forms, merging fiction with literary criticism (the book grew out of a series of lectures Smith delivered at St Anne’s College, Oxford). Not everyone is even sure that it’s a “proper” novel – which probably makes it the perfect candidate for the award.

What I liked most about the shortlist was that its books tend to divide opinion. In different ways, they are all challenging, sometimes awkward, not always “easy” to read. Artful troubled some critics and didn't receive unanimous praise. I personally found Red or Dead by David Peace (an author I much admire and whose previous novels I’d enjoyed) almost insultingly rebarbative. Some agreed with me; others loved it. What I do acknowledge, however, is that it is admirably defiant. Peace has always tried to do new things with his fiction, and in Red or Dead he stretches his ethics of repetition to its elastic limit (snapping it, in my opinion). One critic I know described it to me as “a kind of anti-novel”, which I think is true. Whatever the case, it’s impossible to feel lukewarm about it.

But the best thing about this inaugural award was the choice of winner. (I should at this point confess to having missed Philip Terry’s Tapestry; at least its nomination for the Goldsmiths has prompted me to order it from my local bookstore.) A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride is by the far the most exciting novel I’ve read this year. Its urgent, wholly unique voice transforms what is in some ways a relatively conventional story – the linear narrative from birth to early adulthood of a girl growing up in small-town Ireland – into a head-long plunge into another person’s life and chaotic emotional development. It is bruising, breathtaking, entirely compelling, extremely sad and often very funny. I’m not the only person I know who has already read it twice. I’m also not the only person who was reduced on both readings to streams of tears. McBride’s novel shows us, as do all the nominated books, in their different ways, that form must be the perfect complement to content: a point that Tim Parnell made when announcing the award.

The Goldsmiths Prize is fantastic news for an author who took eight years to get her book published in the first place (the tale of the novel’s gestation is a drama in itself). It’s fantastic news for Galley Beggar Press – an excellent, small outfit run from Norwich on a tiny budget (look out, in particular, for Jonathan Gibbs’s debut novel, Randall, or The Painted Grape – out next year – which, if a recent reading is anything to go by, should be excellent). It’s fantastic news for literature as a whole. And – dare I say it? – it’s fantastic news for “prize culture”. The Goldsmiths Prize may not “replace” the newly expanded Man Booker, as some critics have rather cheekily been suggesting, but if this first year is anything to go by it is already fulfilling a need: for the recognition of genuinely novel novels.

The only downer on the night was the missing “p” on McBride’s rather handsome expressionist trophy, which broke off not long after the presentation (we were assured she’d kept the piece in her handbag for future gluing). This left her the winner of the “Goldsmiths Rize”: a sign, if nothing else, of the author’s – and the award’s – ascendancy.

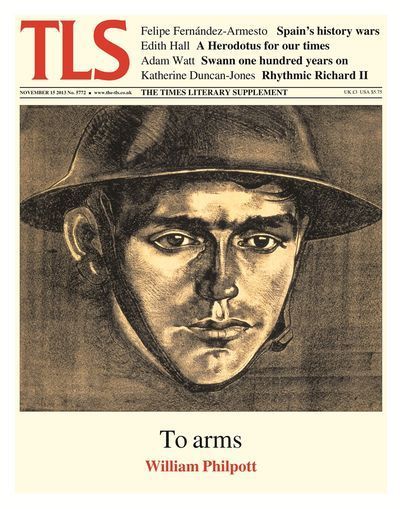

In this week’s TLS – a note from the History editor

With the ill discipline of a less patient age, publishers have anticipated next year’s centenary commemorations of the outbreak of the First World War with a flurry of early histories. William Philpott takes aim at a selection of them, and wonders whether the time is yet ripe for the historians to take over from the memorialists. After the deaths of the last participants, might it be possible to assimilate some of the arguments of academic history into works aimed at a wider public, without risking accusations of insensitivity to the glorious dead?

The First World War does not have a monopoly on remembrance, as Felipe Fernández-Armesto shows in his review of a book on Spain’s own wars of memory, by a former Editor of the TLS, Jeremy Treglown. Fernández-Armesto thinks that “more often than not, appeals to ‘social memory’ are really incitements to perpetuate myths, prolong hatreds and justify conflicts”. In Spain, the bitter divisions of the Civil War took some time to reopen after Franco’s death, but now they are more in evidence than ever. There are a few causes for optimism, but a “realistic consensus on the past” awaits, as with the First World War, a genuine engagement with history rather than the partisanship of disputed memories.

Much of what we mean by “history” was invented by a fifth-century Greek born in modern-day Turkey, whose “pioneering prose treatise sought to explain the nature of the world he inhabited” in a “protean work united by the philosophical question of human happiness”. Those are the words of Edith Hall, discussing the latest translation of Herodotus’ Histories, by Tom Holland. With its descriptions of “princess-rustling” and “heavies”, this is a “twenty-first century Herodotus”, but it is also a translation that leaves this Professor of Classics “in awe” of the translator’s achievement.

Finally, our long-suffering, loyal band of Crossword solvers will notice that this week, we publish the 1,000th TLS puzzle. Of those, 878 have been set by Tantalus, periodically revealed to be Don Yerrill of Dumfries. We are happy to unmask him once again, and salute his splendid contribution to our pages.

David Horspool

November 12, 2013

French literary anniversaries, part 4 – Du côté de chez Swann

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

If literary anniversaries matter at all – and we do seem to be quite keen on them at the TLS – then this week offers a humdinger: the birth of a book rather than an author. November 14, 1913 saw the publication of Du côté de chez Swann. Had that been the end of Proust’s literary career it still would have earned him a place in French literary history, so compellingly strange and original a work was it. But there were a further seven volumes to come, of course, 3,800 pages in all. Readers had to wait until 1919 for the appearance of the second part, À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs – as the anonymous TLS reviewer wrote at the time, “Those who remember the first volume, and who appreciated its qualities, will be happy to know that the cessation of the war has permitted the publication of this work to continue”. (Only four of the eight volumes would be published by the time of Proust’s death at 51 in 1922.)

The groundwork for much of the novel is done in its first part: many of the principal characters are introduced and by the end of it we already feel we know well Charles Swann, Odette de Crécy – not to mention members of the Narrator’s family and of course the cook and housekeeper Françoise; we have also heard much about the Guermantes and Charlus who will come into the picture more fully later. Both the structure and content of the work were already in the author’s mind – as Adam Watt writes in the TLS this week, “the closing chapter of its final volume [was] written immediately after the opening chapter of the first” – all Proust had to do was get it down on paper. Easy!

As is well known, André Gide turned the novel down for the Nouvelle Revue Française, thinking it, on the evidence of the sections he skimmed, the work of a snobbish dilettante – a decision he was to regret for the rest of his life (and a lesson to all publishers’ readers maybe); by 1918, he was writing in his Journal of “Proust’s marvellous book, which I was rereading”, almost as if in a quest for private redemption for his earlier misjudgement.

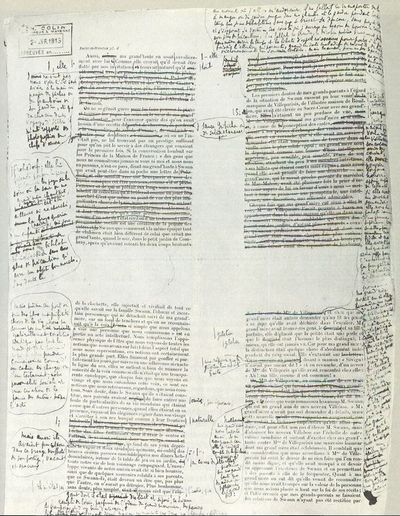

Something for the typesetters to work on: proofs of Du côté de chez Swann (note the working title, "Intermittences . . . ")

Fortunately another publisher, Bernard Grasset, stepped in. William Carter writes in his mammoth and invaluable Marcel Proust (2002) that Grasset regarded the publication of Proust’s work as a “business deal” and had tried to read it “but found it impenetrable”. He told a friend “it’s unreadable; the author paid the publishing costs”.

On the eve of publication Proust set out his artistic credo in Le Temps: “Je ne publie qu’un volume, Du côté de chez Swann, d’un roman qui aura pour titre général A la recherche du temps perdu. J’aurais voulu publier le tout ensemble; mais on n’édite plus d’ouvrages en plusieurs volumes. Je suis comme quelqu’un qui a une tapisserie trop grande pour les appartements actuels et qui a été obligé de la couper” (“ . . . I would have liked to have published the whole thing together, but works are no longer published several volumes at a time. I am like somebody who has a wall hanging too big for the intended rooms and who has been obliged to cut it up”). He points out that his novel “is dominated by the distinction between involuntary and voluntary memory” and goes on to stress that the “Je”, i.e. the Narrator, of the novel is not him, before concluding “The pleasure that an artist gives us, is to introduce us to another universe” – "Le plaisir que nous donne un artiste, c'est de nous faire connaître un univers de plus". He must have known these words could be fully applied to his own forthcoming work.

The first print run was of 1,750 copies, with a number of those going to friends. Among early favourable responses, according to Carter, was that of the Venezuelan-born composer of exquisite songs Reynaldo Hahn, Proust’s one-time lover, who wrote to “Mme Duglé, Charles Gounod’s niece” on November 21: “Proust’s book is not a masterpiece if by masterpiece one means a perfect thing with an irreproachable design. But it is without a doubt (and here my friendship plays no part) the finest book to appear since L’Éducation sentimentale. From the first line a great genius reveals itself and since this opinion one day will be universal, we must get used to it at once”.

The editor of the Figaro’s literary supplement, Francis Chevassu, wrote “an unfavourable account of Swann’s Way in the December 8 issue” (in Carter’s words), acknowledging it as “highly original”, but criticizing it for an absence of plot (not a word helpfully applied to Proust). But Chevassu goes on to say, sensibly: “You must read M. Marcel Proust’s book slowly because it is dense”. Proust dedicated the book to Gaston Calmette, editor of the Figaro, to which he had contributed numerous articles (Calmette was assassinated in March 1914).

It’s gratifying to report that the TLS review was both prompt and favourable. Carter again: “The drama critic of the Times, Arthur Bingham Walkley, wrote a long anonymous piece in the December 13 issue of the Times Literary Supplement. Walkley found similarities between Swann’s Way and Henry James’s A Small Boy and What Maisie Knew . . . . This was a ‘fascinating book’, one whose weaknesses and strengths accorded admirably with the spirit of our times” (whatever that means). Carter tells us that Edith Wharton sent James a copy of the novel, “but it is not certain whether [he] ever read it”.

Carter reveals that in Italy the “writer and critic Renato Manganelli, using the pseudonym Lucio d’Ambra, advised his readers in the Rassegna contemporanea to ‘remember this name and remember this title’ . . . . Proust’s novel was rapidly acquiring many foreign admirers”. At home meanwhile, Cocteau was among those to hail it as a “masterpiece”. The novel had “at least nineteen reviews, notices, and reprints in newspapers – sometimes paid – of favourable reviews . . .” (Proust wasn’t above using his charm and persuasion to try to place reviews).

Lydia Davis, in a translator’s introduction to her 2002 Penguin version The Way by Swann’s, talks of how “many moments [in the book] are . . . so well known that they occupy a permanent place in our literary culture”: the narrator being denied a goodnight kiss by his mother; the dunking of the madeleine in a cup of tea, which calls up involuntary memory, the two paths at Combray . . . . To those who are tempted to identify the Narrator, who is after all called Marcel, with Proust (easily done), Davis says, “this novel is not autobiography wearing a thin disguise of fiction but . . . fiction in the guise of autobiography”; and there are scenes in it which the Narrator could not possibly have been present at, as Proust plays radically with time perspectives.

Interestingly, Davis pays generous tribute to C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s original translation (the first volume of which, Swann’s Way, was completed in the author’s lifetime – the English title caused him anguish as, with his less than perfect English he understood it to mean “Swann’s manner”). She praises Moncrieff’s “sensitive” ear and “adroit handling of the language”. Her own version strikes me as excellent: unadorned, confident and alert to nuance. In compiling useful notes she says that she consulted the biographies of Carter, the Proust scholar Jean-Yves Tadié and George Painter, as well as Edmund White’s short breezy book.

Painter’s two-volume Life (1959 and 65) has rightly been criticized for its overconfident and too literal identification of characters in Proust’s novel with real people. Gabriel Josipovici, writing in the TLS in 1996 (while reviewing the French edition of Tadié’s huge biography), suggested that it “turned Proust’s life into a middle-brow novel” and led some people to think it “was a more than adequate substitute” for the novel itself. But it should be said that Painter completed a huge amount of original research and that, in among the society gossip and fripperies, he delivers many valuable insights. Of course talk of the author having “migrated to the Cities of the Plain”, of “his awakening perversion” or of “the guilt of his Jewish blood” reads absurdly now, but his book is full of amusing anecdotes: at a dinner given by Mme Aubernon, the hostess asks the Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio to talk about love: “‘Read my books, madam, and let me get on with my food’”.

The station at Illiers (Combray)

I recently reread Du côté de chez Swann and was struck by just how much I’d forgotten, so profuse is the detail, beginning with Proust’s handsome dedication to his Figaro editor: “A monsieur Gaston Calmette comme un témoignage de profonde et affectueuse reconnaissance” (“as a token of profound and affectionate gratitude”).

Already on p61 (Folio edition) the Narrator is talking about “l’édifice immense du souvenir” (“the immense edifice of memory” in Lydia Davis’s version).

One of the first of many wonderful passages on reading also occurs early on: “Beaux après-midi du dimanche sous le marronnier du jardin de Combray, soigneusement vidés par moi des incidents médiocres de mon existence personnelle que j’y avais remplacés par une vie d’aventures et d’aspirations étranges au sein d’un pays arrosé d’eaux vives, . . . ” (“Lovely Sunday afternoons under the chestnut tree in the garden at Combray, carefully emptied by me of the ordinary incidents of my own existence, which I had replaced by a life of foreign adventures and foreign aspirations in the heart of a country washed by running waters”).

Perhaps the single most charming moment in the whole novel occurs on p120: the Narrator (not yet ten years old at this point) is disturbed in his afternoon reading by Swann, who is paying one of his regular visits to the family house in Combray; on encountering the boy as he sits in the garden reading a novel by Bergotte (a friend of Swann’s), he offers to have the book signed.

“Je n’osai pas accepter, mais posait à Swann des questions sur Bergotte. ‘Est-ce que vous pourriez me dire quel est l’acteur qu’il préfère ?’

– L’acteur, je ne sais pas. Mais je sais qu’il n’égale aucun artiste homme à la Berma qu’il met au-dessus de tout. L’avez-vous entendue?

– Non, Monsieur, mes parents ne me permettent pas d’aller au théâtre. ”

“I did not dare accept his offer, but asked Swann some questions about Bergotte. ‘Could you tell me which is his favourite actor?’

– Actor ? I don’t know. But I do know that he doesn’t consider any man on the stage equal to La Berma; he puts her above everyone else. Have you seen her?

– No, Monsieur, my parents don’t allow me to go to the theatre.”

(Note the courteous “vous” with which Swann addresses the boy, unavoidably lost in translation.)

The description of the church at Combray is staggering in its detail, as are, of course, the evocations of nature. Elsewhere I’ve noted the priggishness of the composer Vinteuil, the fragrance of asparagus, the thrill of railway timetables, the Narrator’s fishing expedition, Odette “fishing for compliments”, the erotic significance for Swann of the cattleyas, the shocking scene in which the Narrator spies on the late Vinteuil’s daughter as she and her lesbian partner desecrate a portrait of her father during a tryst . . . .

When, in the great finale to the Second Part, “Un amour de Swann”, Swann gradually comes to understand that Odette the ideal and Odette the real person are far apart, the Narrator writes: “Il admirait la terrible puissance récréatrice de sa mémoire” (“He admired the terrible recreative power of his memory”). The crushing realization, after many years, that Odette is “pas mon genre!” (“not my type!”) is one of the most memorable moments in the whole novel.

I only half-remembered Swann’s unrealized project to write a book on Vermeer and had forgotten that he played poker – at the Jockey Club presumably (where one of his models, Charles Haas, had become the first Jewish member).

Elsewhere there is the glorious social comedy of the Verdurins’ “intimate circle”, which Swann, in his obsessive pursuit of Odette, feels drawn into in spite of its philistinism and absurdity, its coarse humour, and casual cruelty offset by occasional acts of genuine kindness.

And the snobbery, not least that of the Narrator who unsparingly tells us, towards the end of the book, how as a boy he recoiled at Françoise’s appearance as she accompanied him to the park near the Champs-Élysées to meet Swann’s daughter Gilberte, with whom he was infatuated – “cette bonne dont je rougissais” (“that maid who made me blush”). The Narrator’s character, in all its complexity, is being formed.

November 10, 2013

The comforts of life and the dancing curator

By MICHAEL CAINES

I can't help but feel bemused by Georgians Revealed, the new exhibition at the British Library, and its emphasis on the affluence and the aspirations of the middle classes during the eighteenth century – not that this is all there is to it, or that what is on display there doesn't impress me a great deal. (And don't take this as an official TLS review, either; that's coming soon, from a much deeper expert in these matters than me.)

On the contrary: I'm glad that anyone who can get into the exhibition, which runs until March 11 next year, can now enjoy the privilege of seeing Jeremy Bentham's violin alongside designs by John Soane, a copy of Eliza Haywood's short-lived periodical The Tea-Table and the exquisite, colourful little volumes of The Infant's Library.

The last room, too, is a treat: a map of London you can walk across in a dozen paces (maybe half? sorry, I didn't count) covers the entire floor. That famous line of Samuel Johnson's, about a man who is tired of London being tired of life, adorns the wall; now you can see, if you didn't realize already, how much smaller was the London he had in mind than the current incarnation.

My bemusement has more to do with attending the press view on Thursday morning fresh from a reading of The First Bohemians by Vic Gatrell, which I reviewed for another paper. In that book, although the author is at pains not to misrepresent living conditions in London during more or less the same period covered by the exhibition, the aspirations, aristocratic pretensions and material wealth of well-to-do eighteenth-century Londoners are treated, I would say, with a certain degree of scepticism.

I must have picked up a little of that attitude. Many of the city's artists, Gatrell observes, lived in the environs of Covent Garden; paid to produce flattering, elegant visions of wealthy patrons, they could hardly have been blind to the deprivations of urban life, to scenes of violent crime, poverty, prostitution, chronic alcoholism, press-ganging and all the other not-so-pleasantries of the time.

I'm not saying that Georgians Revealed ignores deprivation and depravity altogether; it features the nineteenth-century illustration above, for example, as well as references to slavery. But its principal subject is middle-class materialism, and the complementary view of the world. You need to be a certain mood, or be a certain kind of person, to take unclouded pleasure in such displays. Here, Drury Lane is pleasantly free of human traffic, the countryside is bucolic, the teapot is mighty fine china (or something like it; most people couldn't afford the real thing), and one could seek to improve one's social standing by learning how to act proper, like, from the Earl of Chesterfield's letters to his illegitimate son Philip. William Hogarth and Thomas Rowlandson, key figures in Gatrell's history, barely figure here at all.

Instead, there is almost a whiggish version of history here, as summed up in the exhibition's subtitle: Life, style and the making of modern Britain. The last part of that subtitle is crucial. Here are the good things people enjoyed, or emulated, from around the world, thanks to a flourishing mercantile economy; here are innovations such as new forms of transport (the expansion of a network of usable roads being itself a basic improvement); and in the pair of Georgian men's shoes (below) on loan from Northampton Museum, I suppose we have the remains of some popinjay ancestor of today's egregious red trouser brigade.

Thanks to Professor Gatrell, I couldn't help but wander through the exhibition with some less-than-stylish visions of eighteenth-century life coming to mind. I'll have to wander through it again after brushing up on my Chesterfield.

Never mind: you don't even need to go to the BL to see Moira Goff, the world's first dancing curator, introducing the exhibition.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers