Peter Stothard's Blog, page 55

September 13, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

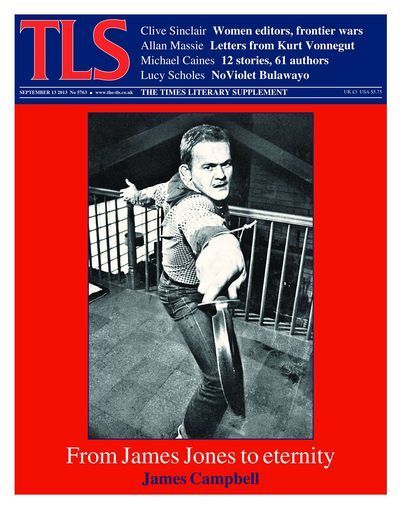

From Here to Eternity is a novel about soldiers waiting and training

for a world war which must inevitably come. When it was published in 1951,

this debut by James Jones was a pioneer, says

James Campbell this week, in shocking a civilian readership with “the

brutality of peacetime army life”. The characters “converse like hoodlums

working up to a brawl” and the title, taken from Kipling’s

“Gentlemen-rankers out on a spree, / Damned from here to eternity”, is used

for a book that “lacks the gentlemanly part”. The new edition restores

expletives and sexual episodes originally excised, an editorial decision

that increases the book’s already excessive length. A bolder decision “to

improve pace and fortify succinctness” would have been to move in the

opposite direction. Kurt Vonnegut made his name with his novel of the

fire-bombing of Dresden in 1945. His newly published letters run from his

prisoner of war’s return to peacetime life, through the best-selling years

of Slaughterhouse-Five, to his death in 2007. Allan Massie muses on

a great American literary life in which Vonnegut kept his readers more

easily than he maintained the support of the critics. Clive Sinclair looks

back at America’s domestic wars and, in particular, the role of women

fighters described in Christine Bold’s book The

Frontier Club. Many wives, it seems, joined the shooters-to-kill

but allowed themselves to be written out of the official reports – only, of

course, after they had also edited the stories for posterity.

The Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid spent the war in the Shetland Islands under

intermittent surveillance as an outspoken Communist Party member. His

self-imposed exile to what Andrew McNeillie describes as “close to a Siberia

of his own” produced some masterpieces of modernism as well as a letter to

one of his investigators in London that is a magnificent serving of vitriol

in itself.

Lesley Chamberlain praises “the immediacy and bite” of Alison Macleod’s novel Unexploded,

set after the evacuation of Dunkirk when the people of Brighton are

expecting a German invasion.

Peter Stothard

September 10, 2013

Sign language

by TOBY LICHTIG

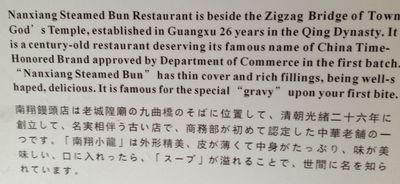

Official language is so intrinsically humourless that it's always a pleasure to see it get mangled. I'm often amazed by poorly translated notices in museums and public places: surely if you're going to the trouble of getting a sign made up in the first place it can't be too difficult to get someone with an idiomatic grasp of the language to cast an eye over it.

Today, however, the ubiquity – and cheapness – of computer translations has if anything littered the world with more bizarre official renderings than ever. And, on a recent trip to Shanghai, I amused myself by taking note of some of the city's more surreal offerings.

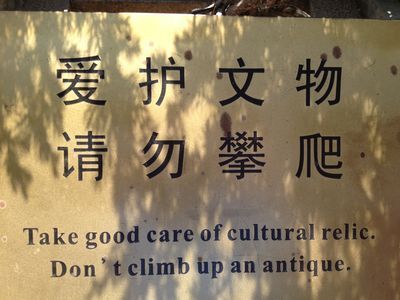

I was delighted, for example, to receive the following advice in the Garden of Leisurely Repose (an enchanting translation in itself).

The garden itself is a paradise of charming nomenclature, and includes, among other pleasures, "The Corridor for Approaching the Best Scenery"; "The Pavilion for Viewing Frolicking Fish"; and "The Tower of Containing Watery Jade".

Round the corner, visitors can treat themselves to a selection of delicious dumplings at a restaurant whose name is celebrated in the following notice:

And it isn't only signs that carry useful information. I particularly enjoyed the following piece of quiet wisdom, emblazoned on this man's T-shirt.

On the subway, customers are warned about the dangers of the electronically operated doors:

The following explains how to use the museum guide:

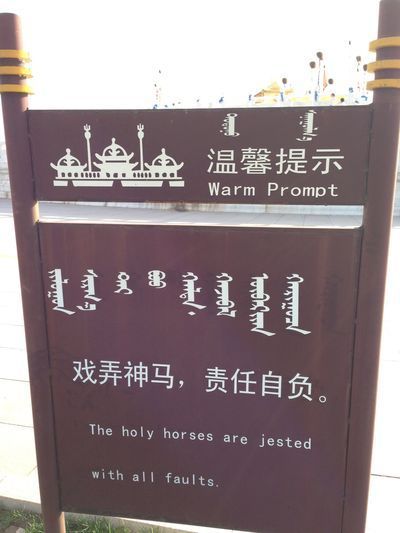

But my favourite sign of the trip came courtesy of a Chinese translator and editor to whom I was speaking about the matter. She told me that the standard of translation in Shanghai is far better than that in Inner Mongolia, where she had recently been on holiday, and where she had spied the following sign, asking visitors not to disturb the wildlife.

September 8, 2013

Death of a bookshop

By MICHAEL CAINES

When I last picked up a copy of the London Bookshop Map a couple of years ago, it listed some eighty-seven independent bookshops, of which sixteen were south of the river. The new edition is due to be published on Thursday and seems set to list twenty more shops; at least a couple of those formerly listed for South London have closed in the past year, however, for the inevitable, predictable reasons: Amazon and the rising rents or business rates (so much for government lending small businesses a hand).

The latest closed yesterday: My Back Pages in Balham (one of the Gateway to the South's "quaint old stores"?), as featured in the TLS last year and the year before that.

For local idlers, this meant saying goodbye to a fine place for browsing/procrastinating, hunting out the novel you didn't know you wanted (eat your virtual heart out, Amazon), and losing yourself in a small maze of tall shelves, some of them reassuringly crowned with hardback "non-movers" (Hugh Walpole and Henry Treece, say), others offering the occasional surprise – eg, my last purchase (or the last I'm owning up to), The Unwriter & other poems by Gerard Woodward, Sycamore Press, 1989.

Bargains aside, the getting lost was certainly part of the fun. "Some people seem to enjoy the business of hunting out books as much as they enjoy reading them", a wise man once said. That's perfectly trueas long as you can take "hunting out" as a euphemism. Bumbling around bookshops has to be the slowest form of hunting on record – children can grow up knowing that their parents are somewhere out there, in Hay-on-Wye or Cecil Court – unless, that is, the entire stock has to go in the next forty-eight hours. At that point, there can be what passes, in bookshop terms, for a feeding frenzy.

I suppose I saw exactly that during my last visit to My Back Pages. We eleventh-hour bargain-hunters clogged the maze. The tall shelves stood in unfamiliar positions, preparing themselves for departure. One man had brought a shopping cart on wheels with him. The history and biography sections were permanently occupied. American fiction was proving troublesome, being the most attractive feature in a narrow central aisle.

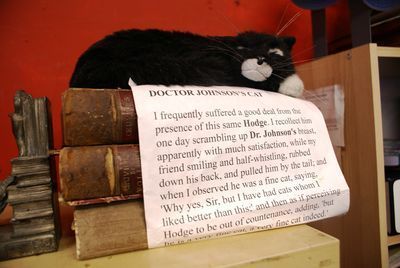

It must have been interesting to see the old place so busy, from the shopkeeper's point of view. I paid up and said goodbye to him – and to Doctor Johnson's cat:

No doubt worse things happen both at sea and in SW12 than the death of a bookshop; I suppose its patrons will just have to find other ways to procrastinate.

(NB Of this year's earlier closures, the Lion and Unicorn, the children's bookshop in Richmond, est. 1977, a reliable source tells me that "customers" would go in to ask for advice and handle the merchandise, even to photograph the covers for reference, before buying online. Since people rightly want to try before they buy, a real bookshop has to stand in for the virtual one – what are the chances of Amazon paying a kind of finder's fee? Ah – slim, you say . . . .)

September 6, 2013

Matisse in Nice – the palm trees

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Nice: city of the festival of flowers and grand seafront hotels, home to

Russian émigrés and escapees from the English winter; fertile ground for the

far-right Front National (as are Toulon and Marseille, further down the coast),

and host for the athletic Jeux de la Francophonie, being staged later this

month.

France’s most

recent Nobel laureate for literature, J. M. G. Le Clézio, was born in the city in

1940; it provides the setting for his remarkable first novel Le Procès-Verbal (The Interrogation,

1963), as well as for the opening section of the very fine (and as yet

untranslated) semi-autobiographical Révolutions

(2003), a novel that I don’t sense has yet received its proper due.

Meanwhile, to mark

the fiftieth anniversary of Nice’s Musée Matisse, the city has staged eight

(eight!) exhibitions relating to the artist's work, under the banner “Un été pour

Matisse”. The mammoth project (over 700 works) was put together by Jean-Jacques

Aillagon, a former minister for culture. Le

Monde’s art critic Philippe Dagen (his review, on July 23rd, was

headed “Nice rend justice à Matisse” – it seems the temptation to play with the

two names is a common one) had reservations about the concept, citing cases

where city authorities had merely tried to cash in on an artist’s name, but he

was won over by the quality and variety of the displays. It sounded like one

not to be missed.

Henri Matisse, who was

from the North, moved to Nice in 1917 (he was born in 1869) and spent most of

the rest of his life there until his death in 1954 – he decamped to nearby Vence

for part of the war to escape the threat of aerial bombardment of the city. In

common with so many painters he was attracted by the light – “Quand j’ai

compris que chaque matin je reverrais cette lumière, je ne pouvais croire à mon

bonheur!” he wrote to a friend.

The fruits of the happy marriage between artist and environment are

amply on display in the beautiful Musée Matisse in Cimiez at the top of the

town; to mark the anniversary, the artist’s family have bequeathed to the museum

a vast ceramic frieze (2.3 x 7.9 metres) entitled “La Piscine”. In the nearby

Archaeological Museum, the watery theme is explored in the exhibition “À propos

de piscines”, which imaginatively combines works from the museum’s collections

(the museum is sited next to some Roman thermal remains) with modern pieces:

videos, including an eerie seven-minute “Reflecting Pool” by Bill Viola (1977–9)

which was so disconcerting I had to watch it twice. Also on display was David

Hockney’s slightly creepy “Portrait of an artist (Pool with Two Figures)” and

an accompanying video.

Most

revealing (to me) was Matisse’s debt to the Symbolist and mystic Gustave

Moreau, eloquently demonstrated in “Gustave Moreau, maître de Matisse” at the

Musée des Beaux-Arts. Matisse spent five years from his arrival in Paris in

Moreau’s studio, and learnt much: “Avec Moreau on avait la liberté de forger ses

moyens d’expression suivant son propre tempérament” ; he later wrote "Un

seul professeur compte pour moi. C’est Gustave Moreau”. Another artist, Henri Evenepoel spoke of Moreau’s “talent, generosity . . . amiability, superior mind . . . " .

Moreau

didn’t travel. “According to Marie-Cécile Forest, writing in the accompanying

catalogue, he “wasn’t strictly speaking an orientalist painter. He

doesn’t depict an anecdotal Orient but rather an imagined one discovered via exhibitions,

books". A generous selection of loans from the Musée Gustave Moreau in

Paris reminds viewers of his strange, fevered imagination. The poet, Resistance

member and museum director Jean Cassou spoke of "un mystère Gustave

Moreau”. For my part, I couldn’t help thinking that the delicate charcoal

sketch of a Persian poet (1890) is altogether finer than the oil painting that

followed it. (The exhibition also acquainted viewers with the work of the Niçois Symbolist artist Gustav-Adolf Mossa, whose "Fœtus" is the one of the most unpleasant and disturbing paintings

I’ve ever set eyes on.)

The palm tree has

long been the “emblem of the Côte d’Azur”, according to Aillagon’s fascinating and

learned catalogue essay, which illuminates “Palmiers, palmes et palmettes” at the sumptuous Musée Masséna behind

the Promenade des Anglais: rather than trunks, palm trees have stalks or stipes that are usually of the same diameter from top to bottom and don’t ramify. The

tree, of a wide variety of species, is ubiquitous (see below)

. . . think of the

Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival).

This brilliantly

conceived exhibition looks at the use of the tree in art, from biblical scenes

to historical ones: Louis Francois Lejeune’s spectacular panorama of “The

Battle of Aboukir” (1805) is framed by the trees. Bonnard, Dufy and Picasso all

made good use of them, as of course did Matisse, whose “Tempête à Nice” (1919–20)

was clearly inspired by Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s photograph of a storm in Nice

in February 1915.

The local paper Nice-Matin has hailed the eight exhibitions

as a triumph, citing visitor numbers of 176,000 and counting. They’re on until

September 23. I managed to catch four of them, but would gladly have taken in

“Matisse: Les années Jazz”, “Femmes, Muses et Modèles”, “Matisse à L’Affiche”

(advertising posters) and “Bonjour Monsieur Matisse”, which looks at his

influence on other artists, American artists in particular. Instead I’ll make

do with the superb exhibition catalogues, which include reproductions of two

works by Sophie Matisse (born in Boston in 1965). She looks to have inherited

something of her great-grandfather’s genius with colour.

September 4, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

What we see in ancient Rome has always been coloured by what we want to see.

Seventy years ago, while fascists stalked Europe, the Roman Republic was an

oligarchy behind a democratic mask. Today, says Mary Beard, the fashion is

to seek the democratic aspects again. Some very slim shards of evidence are

used to justify both positions, and this week our Classics editor offers two

helpful warnings to readers who might become confused. The first is to watch

the space set aside for small print at the bottom of the page: “the more

space the footnotes occupy, the less likely they are to prove what they are

supposed to”. The second is to watch for conveniently modern jargon

translated from unfamiliar Latin words: “the more cod Latin that is

sprinkled over any discussion of Roman history, the less well founded the

argument is likely to be”.

In few discussions of the ancient world has there been greater imagination,

wishful thinking and fraud than on Roman Britain. The British shift from

tiny part of great empire to massive imperialists in our own right has long

encouraged the creators of patriotic narrative. Emily

Gowers reviews Charlotte Higgins’s much-praised book Under Another Sky,

in which the author’s journey around the remains of mosaics, camps and towns

becomes “a brilliantly constructed and often exhilaratingly poetic treatment

of wider themes”. Marina Warner considers Edith Hall’s “superb and richly

detailed study” of how Goethe and Stalin, among others, obscured our

understanding of Iphigenia’s time beside the Black Sea.

One of the most extraordinary classical translations of recent times is A. E.

Stallings’s version in verse of De rerum natura by Lucretius.

Sarah Knight quotes from Stallings in her review of an earlier translation

by Lucy Hutchinson, another great woman translator of this materialist

masterpiece. In the seventeenth century the potential offence against

Christian piety was as much an obstacle to her art as the problems of the

poet’s philosophical Latin.

Peter Stothard

The TLS Poem of the Week is excerpted from “The Tollund Man in Springtime” by Seamus Heaney, who died last week.

August 31, 2013

Calvino's San Remo

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Italo Calvino was born in Cuba (in 1923) but grew up in San

Remo on the Ligurian coast. His first, raw-edged, novel The Path to the Spiders’ Nests (1947) drew on his experiences with

the partisans in the hills and valleys behind the town. As he writes in a 1964 preface

to that book, “I was from the Western Ligurian Riviera. In polemical spirit I

obliterated the whole tourist coastline from the landscape of my home town . .

. : the palm-fringed promenade, the Casino, the hotels and villas. It was

almost as though I was ashamed of it”.

In July 1945 he wrote to a friend in Rome “San Remo is in a

real mess from the constant naval and aerial bombardments”. (This is from the

new edition of Letters 1941–1985, which will be reviewed in a

forthcoming issue of the TLS.) By

1947 things are looking up: “This is a wonderful town where you can still bathe

at this time of year” (January!). In 1950 he reveals to Natalia Ginzburg that

San Remo “is the only place in the world where I can live in studious and

fruitful peace and solitude . . . . I spend the afternoons on some rocks here,

belly in the sun, reading Thomas Mann, who writes very well about things that

are completely incomprehensible to me”.

More than once Calvino reveals that he always says “’Born in

San Remo’. An exotic birthplace [i.e. near Havana] is not informative of

anything.” He writes with fondness of the town, in the autobiographical Road to San Giovanni: “There were years

when I went to the cinema almost every day and maybe even twice a day, and

those were the years between ’36 and the war, the years of my adolescence. It

was a time when the cinema became the world for me . . . . I would go to the

cinema in the afternoon, slipping out of the house on the sly, or with the

excuse that I was going to study with some friend or other, since during the

school term my parents allowed me very little freedom”.

He has “one cinema in particular” in mind, “the oldest in

the town and one connected with my earliest memories of the days of silent films”

(see below – the cinema itself is clearly closed for August).

His “period” as a film buff went “pretty much from Lives of a Bengal Lancer, with Gary Cooper, and Mutiny on the Bounty, with Charles

Laughton and Clark Gable, up to the death of Jean Harlow, . . . with plenty of

comedies in between”.

The novelist draws interesting parallels between his

experiences and those of the director Federico Fellini, whose work “very

closely approximates my own cinema-goer’s biography . . . . he and I are almost

the same age, and . . . both come from seaside towns, his on the Adriatic, mine

in Liguria, where the lives of idle young boys were pretty similar (although in

many ways my San Remo, being a border town with a casino, was different from

his Rimini”.

Calvino, who died in 1985 (his dates, incidentally, closely match

those of Philip Larkin), won’t have seen the lifesize statue in the town centre of

the New York-born Italian TV host Mike Bongiorno, who for several years hosted

the Sanremo Music Festival in the Casino. The town favours the spelling of its name as one word – and has named one of its thoroughfares, below, after its most distinguished

son. As Calvino wrote to Umberto Eco in 1962, in response to an article by the

prolific polymath: “What is the stuff about the San Remo Festival? Never heard

of it!”

But the Casino is of course still there, and very handsome it

looks too. Parked outside on the Friday afternoon I recently walked past it was a black Bentley

with Qatari diplomatic number plates. Different times.

August 30, 2013

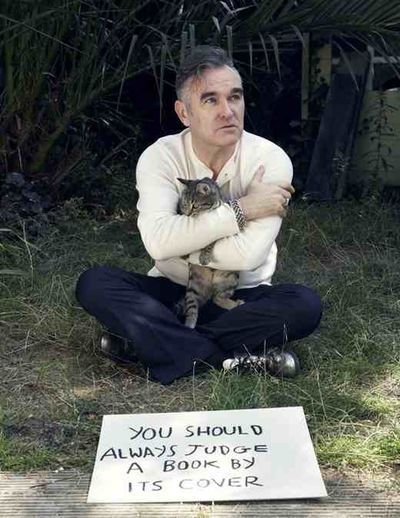

Morrissey unbowed

By ALAN JENKINS

There’s nothing like pop music for bringing people together – or for dividing them, a kind of tribal warfare by other means. Take Morrissey – as, in the years when he enjoyed unequivocal fame and success, with The Smiths, I mostly couldn’t. (I was probably about ten years too old.) In the twenty-five years since, though, he seems to me to have grown in stature as well as in girth. The nicely pointed combination of Johnny Marr’s cheerful guitar tunes with the cheerless ironies of Morrissey’s lyrics to which I failed to respond in the 1980s has become an immeasurably more seductive mix of gorgeous melodies, powerful, rockabilly-inflected rhythms and, driving it all, the long, agonizing melodrama that is being Morrissey.

This last may have deepened and darkened with the years but it isn’t really new, of course:

The boy with the thorn in his side

Behind the hatred there lies

A murderous desire for love

How can they look into my eyes

And still they don’t believe me?

And if they don’t believe me now

Will they ever believe me?

– that was Morrissey with The Smiths, in 1985. There are plenty who still don’t believe him, and elbowing their way to the front of his detractors, always, are the self-styled apostates. Their testimonies run to a simple formula: I used to love Morrissey: here’s how much! Then I interviewed him/ read an interview with him/ heard one of his latest songs and now I don’t anymore. The tone they favour is “more in sorrow than in anger, but — still pretty angry, actually”. Morrissey 25: Live, released to celebrate – if that is the word, of which more later – his twenty-five years as a “solo” artist, and the singer’s first live concert film since Who Put the M in Manchester? (2004), has already occasioned a couple of such pieces. It’s a funny phenomenon. These fellows seem to be annoyed that he made them copy his haircut back in ’86.

Well, so what. If Morrissey is not for you, or not for you any more: fine. But if he is, you’ll find the new film riveting and moving to the extent that you find those adjectives apply to the man. The venue is Hollywood High School, in whose classrooms once sat Lana Turner, Judy Garland, Fay Wray and Carole Lombard (though not all in the same class, one hopes for the teacher’s sake). In its intimate 1,800-seater auditorium Morrissey plays a nineteen-song set drawn from the whole span of his quarter-century, nine-studio-album post-Smiths career, which, as even the most devoted of his admirers will admit – not without a certain outrage of their own – has been an up-and-down affair.

But Morrissey triumphs over detractors, ill fortune and his own intransigence by turning all these to fiercely compelling account in his songs, in his voice, in his comportment onstage and off. The film (directed by James Russell) captures an authentically charismatic presence striding the stage, whipping the microphone cord around him, clasping the desperately outstretched hands of an audience from whom his every gesture solicits the impossible: a love sufficient unto his needs. Morrissey is a powerfully built man these days, and it’s wonderful to see him thrashing, throwing back his head and beating his chest, falling to his knees beseechingly before the projected images of battery farms and slaughterhouses (“Meet Your Meat”) that accompany a caustic, swirling rendition of “Meat is Murder”. Other highlights are the sinister London phantasmagoria “Maladjusted” (“You stalk the house, in a low-cut blouse. Oh Christ, another stifled Friday night!”), the as yet unreleased “Action is My Middle Name” (“Action is my middle name, I can’t waste time any more. Everybody has a date with an undertaker, a date that they can’t break”) and “You Have Killed Me” from his 2006 album “Ringleader of the Tormentors”.

For those of us who have grown middle-aged with (or before) Morrissey, there is a new poignancy in his wrestlings, explicit or otherwise, with our common mortal lot. And from beginning to end, there is barely any let-up in the intensity with which he expresses his own peculiar impasse, the unstoppable force of his narcissism meeting the immoveable object of his self-disgust. In the course of expressing it, he blooms out of (I think I counted) four beautiful shirts, as is his way, throwing one to the crowd at the climax of “Let Me Kiss You”.

As ever, Morrissey’s relationship with his Los Angelean fans is generous, humorous (“You mustn‘t whoop if you don’t want to”; “What’s your name? Kevin? David? Devin. Good name”) and – in contrast to the difficult conditions and unresolvable torments he sings about being in – beautifully unconflicted. “Thank you for singing so open-heartedly”, says one tearful celebrant, as the mic is passed to her. That about sums it up.

The film ends with the further testimonies of devotees as they leave the concert, flush-faced and inspirited. One of them hopes that we’ll be seeing a lot more Morrissey shows in the years to come. I hope so too, but it’s not looking good. Earlier this year, after battling through a series of health crises, Morrissey was finally felled by a bout of food poisoning and was forced to cancel what would have been a triumphant tour of South America. (He has a huge Latino following north of the border too, and indeed opens this show with a joyous shout of “Viva Mexico!”) He is currently without a recording contract and, given his proud refusal to bow to the downgrading of the artist that accompanies “the new reality” as the night follows day, he seems unlikely to attract one soon. “The future is suddenly absent”, he writes on his fansite true-to-you.net: “the wheels are finally off the covered wagon. Cancellations and illness have sucked the life out of all of us, and the only sensible solution seems to be the art of doing nothing”. He sounds abject, and the bulletin is distressing to read. It is preceded by a line from a no less abject poem, from A Shropshire Lad, whose sentiment is similarly shunless: what to do?

If it chance your eye offend you.

Pluck it out, lad, and be sound:

‘Twill hurt, but here are salves to friend you,

And many a balsam grows on ground.

And if your hand or foot offend you,

Cut it off, lad, and be whole;

But play the man, stand up and end you,

When your sickness is your soul.

August 29, 2013

Reintroducing Miss Nobody

By MICHAEL CAINES

A century ago, the civil servant Claud Schuster reviewed a striking book for the TLS: Miss Nobody by Ethel Carnie. It showed “great promise”, he thought, despite its faults; its depiction of “some of the lowest paid of female labour” was “wonderful vivid and powerful”, and its heroine, Carrie Brown, struck him as a “real person”, a working-class lover of “penny novelettes” with “that tough, rather grim, and rather gay determination of the Lancashire working classes which is so difficult to present in literature”.

Miss Nobody seems to have been remarkable for both the reasons given by Schuster and its supposed status as the “first published novel by a working-class woman in Britain” (as it’s described in the imminent reissue edited by Nicola Wilson, with an introduction by Belinda Webb). Yet recognition for Carnie has been rare in the years since she wrote (there were to be a further nine novels, as well as contributions to the newspapers and volumes of poetry). This seems unfair to a writer who can conjure up Sunday morning in a “low lodging-house” (“Beds, fourpence. Men only”) like this:

“Church bells were contradicting and wrangling with each other from a score of steeples. The strong rays of the glorious sunshine shone in at the windows of the long room, making its dust a path of gold-motes and its bareness not quite so bare.

A man huddled over a pot of beer lifted his head to hear a woman’s voice in the place, then took a long drink to inspire forgetfulness. . . .”

Perhaps it doesn’t help that her authorial identity isn’t quite settled – Carnie was her maiden name, Holdsworth her married name, and they sometimes appear in combination – and Miss Nobody has to strike an uneasy alliance between romance and realism, in an attempt to fulfil certain generic expectations (acknowledged in the protagonist's love of "penny novelettes") and convey the grim grind of working-class life in Manchester (for which see below). Lifetime editions of her books now seem to be scarce. Webb, in her introduction, puts forward another argument. Ethel Carnie, she suggests, has been “silenced”:

“Not by any one person, but by our learned literary and political institutions. That is a strong statement but how else can it be described when the first known working-class woman novelist has barely been heard of amongst feminist and literary theorists – let alone by anyone else?”

A conference at the Working-Class Movement Library in Salford, on September 7, accompanies the launch of the reissue, and there’ll be a second TLS review of the book in due course – for the moment, here’s a taste of the novel’s unsparing humour (more in a Jonsonian than a colloquial sense), in a “wonderful vivid” description of workers going on strike.

*

A feeling of dissatisfaction in Room 7 made itself felt. Three months before there had been a strike, but Room 7 had gained nothing but hunger by the transaction. The girls and women talked in little knots in the meal-hours, when they came into the long room where Carrie worked, to dine with their friends. The dissatisfaction was a murmur at first, then swelled louder and louder, but still Room 7 felt its own impotency unless the other rooms backed it up.

One day, Carrie, as they were all sitting at breakfast and had been discussing the state of things, jumped up, stood on an upturned waste-can, and made an impromptu speech, full of grim humour, fire, and a sense of justice. She asked the girls to back up Room 7, and join the Union, those who were not in it already, and fight, like Englishwomen. They listened with mirth at first, knowing her aptitude for a joke, but her fire of words at length stirred their blood.

Just as they clapped their hands and she stepped down, Dick Jones, the boss, swung out of the lift. How much or little he had heard could not be guessed, but something certainly, by the gleam in his eyes.

“He’ll be down on you, Carrie, for this,” said an old worker sympathetically.

“What do I care? If Room 7 gets a rise they’ll enjoy it when I’ve gone,” she laughed, and perhaps this brave, laughing speech inspired the girls and women to suffer again for the sake of Room 7.

All the workhands joined the Union, which was indeed very poor in funds.

The morning came when the toilers in Room 7 refused as one woman to work for seven-and-six. They boldly demanded a rise of ninepence, saying the machines should stand idle else. Jones cursed them all round, and told them he wanted none of their damn nonsense, and ordered them to knock the machines on. He told them that the other rooms would not back them up for more than a week or two.

Some of the other hands who had wandered in near the doorway to see the scene shouted “Won’t we? Try us!” Jones came up from the office with the verdict that there would be no advancement. They took their shawls and overskirts and filed out into the street. The throb of the machines in other factories came to them with a sound of prosperity.

Carrie and Fanny passed the first day washing up old blouses and bedding in the damp scullery. They told each other cheerfully that the battle would be brief.

The Battle for Ninepence began.

City papers reported it when there was a few inches of space between society chit-chat, the winter’s fashions, and musical critiques. Preachers talked solemnly from the pulpit of the spirit of unrest abroad in the land, and regretted a materialistic conception of life that kept the toilers from the inner light. People quarrelled as to which side was in the right.

Not hearing the voices of public opinion, the strikers hung on, going paler and thinner each day, crying each time they left the strike-meetings, “Are we downhearted? No!”

From scrap meat to ham-bones, from ham-bones to butterless bread – credit refused in many cases – everything sold that could be done without, and always the thought haunting them that if they would merely consent to give in they could get meat again. It haunted them as the landlord stood on the tattered doormat and looked askance, and as the children whispered for more and could not have it – but most of all as the papers began to appear in the grocers’ windows, saying in bright, red letters “Join our Club!”

But they did not give in.

The weeks crept by, each one longer than the last. They felt that they were clinging now as mariners to a spar. . . .

August 28, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

Between the late nineteenth century and the Second World War, Berlin grew

apace – Mark Twain called it “Chicago on the Spree”. And unlike London,

Paris and Vienna, cities that had grown over centuries, with a rich cultural

tradition, Berlin, “the quintessential modern city”, “raw, vigorous, ugly

and haphazard”, simply mushroomed, “with the minimum of planning”. Ritchie

Robertson reviews an anthology of writings by architects, planners,

journalists, philosophers, sociologists, essayists and novelists, from the

famous – Walter Gropius, Walter Benjamin, Joseph Roth – to the unknown, and

finds it “astonishing in its range”. The Soviet Union in the same years

would seem the last place where you’d come upon a haunted castle – but the

Gothic was alive and well in Soviet culture, with its abandoned factories,

unfinished construction sites and communal apartments where the dead

“stubbornly refuse to stay in the ground”. Muireann Maguire’s study of

Soviet Gothic and her translations of tales in this unlikely genre are

reviewed by Eliot Borenstein. Growing out of a contiguous sub-soil, the

“unusually well-crafted tales” in Stephen Romer’s “beautifully translated”

anthology of French Decadents feature “snobbish perverts plotting the

satisfaction of their peculiar lusts”, Baudelairean ennui and necrophilia.

Graham Robb welcomes some minor, forgotten masterpieces – misogynistic as

they unfortunately are.

We devote several pages this week to Literary Criticism, which has undergone

several transformations in the lifetime of this editor, let alone of this

paper. Joseph Phelan spots the elephant in the room, writing “what we

actually hear in [The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, Volume Six]

is academics talking to each other, and hoping or pretending that someone

elsewhere is listening”. One thriving area is the “recovery” of buried women

writers; Susan Civale reviews new studies of Jane Austen’s less well known

contemporaries. Alicia Rix and Claudia L. Johnson both focus on the ways in

which we continue to seek the

great Jane “herself”.

Alan Jenkins

Holiday reading, Italian style

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

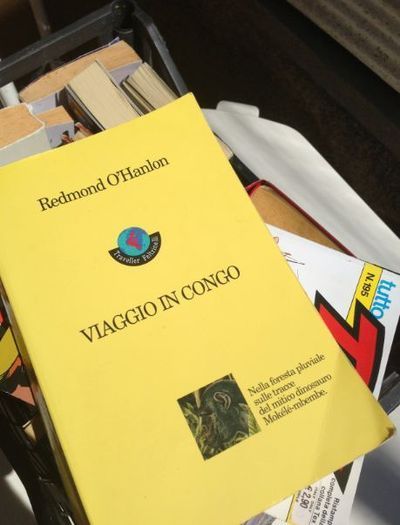

On holiday in Liguria, northern

Italy, recently I saw gratifyingly few electronic reading devices: the odd one on the

beach but that was really about it. Being nosey, I don’t much care for others’

use of e-readers and tablets – I like to see people’s choice of books. So alongside the Jo Nesbøs and the odd Dan Brown, I

spotted, poolside, an Italian translation of a novel by Ali Smith and a heavily

bearded guy in the corner reading Hell’s

Angel. Cinquanta sfumature di grigio

reared its head, inevitably – that’s a book where a tablet

would have come in handy.

And if people ran out of reading

material between doing lengths and dive-bombing into the pool they could always dip into the basket provided by the genial owner of the bar: not just magazines or guidebooks to Costa Rica, but a good

selection of Isaac Asimovs, Redmond O’Hanlon’s Congo Journey, which the publishers Feltrinelli intriguingly describe as a

novel,

. . . an Italian translation of La Lampe

de Psyché by the French nineteenth-century eccentric Marcel Schwob, Dante, Sciascia, Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo,

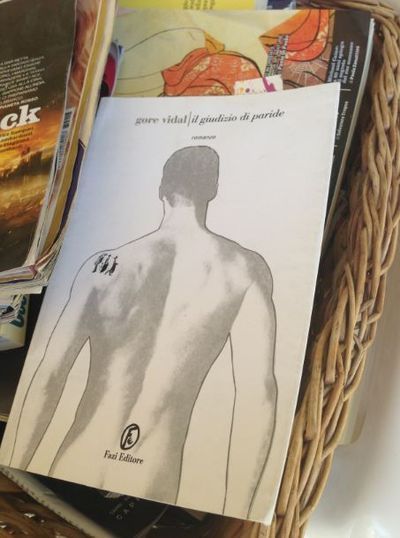

a novella by Joseph Roth, Gore Vidal’s Judgment

of Paris (below) – a pretty highbrow selection on the

whole.

Personally I’ve always been allergic

to those summer reading recommendations the papers go in for: “I’ll be taking

with me the new McEwan/Boyd/Mantel . . . “). But I did admire – “enjoy”

would not be the right word here – Deborah Levy’s short novel Swimming Home (2011), in which every character

is thoroughly unlikeable. Levy creates a disconcerting atmosphere that stays

with you long after the holiday is over.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers