Peter Stothard's Blog, page 58

July 5, 2013

Art under Attack

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Stepping off the chewing-gum-peppered pavements of

the City of London this morning, I found myself in a cool antechamber to the chapel

of the Worshipful Company

of Mercers. Having arrived early, I drifted between sombre

portraits of the grand old men of the Company’s history as I waited for others

to join me. The occasion was the unveiling of Tate Britain’s

next major exhibition, Art under Attack:

Histories of British iconoclasm (opening in October), which aims

to trace incidents of physical attack on our art from the 1500s to the present

day.

Once gathered, we

were invited to move beyond the table of breakfast pastries into the chapel

where “Statue of the Dead Christ” – one of the show’s central works, on loan to

the Tate from the Company (hence this morning’s venue) – lay in wait.

"Statue of the Dead Christ", c.1500-1520; Stone on limestone plinth; the Mercers’ Company

This delicately carved figure of Christ removed from the Cross, his features (and limbs, were

they still there) contorted by the early stages of rigor mortis, ribs and veins

seeming almost to pierce the surface, is a powerful historic reminder of this

country’s relationship with the visual arts. Dating between 1500 and 1520, the

statue fell prey to Protestant iconoclasts, who stripped bare monasteries

across the land as part of Henry VIII’s systematic drive for more money to keep

him in the style to which he had grown (the right word) accustomed.

This statue will

join others from the period – mostly limbless, with great gouges where books

were cleaved from the stone. These were not acts of opportunist vandalism;

those armed with the axes knew very well that sculpted books were lined with lead, a

material of greater value than any amount of stone.

The lead, found there

and elsewhere in the monasteries, was generally melted down on site to form

ingots – and for this great fires were required. How fortuitous, then, that

monasteries had libraries too – so many pages to burn. (In the press

conference which followed our preview, Tabitha Barber, one of the exhibition’s

curators, offered the startling if difficult-to-substantiate statistic that 90

per cent of pre-Reformation images have been lost, and all that remains is

mutilated: one poignant photograph taken in 1907 following an excavation at

Winchester Cathedral shows row upon row of disembodied heads and limbs.)

Alongside these

statues will be exhibited religious artworks and manuscripts (two fragments from the tomb of Thomas

Becket show how literally the 1538 Court Order to deface all images of the saint

were taken).

But, if we are

to cover 500 years of this stuff, we must trot on to the second phase of the

exhibition, which covers secular forms of iconoclasm. Public sculptures are

obvious targets. Such is the case of the statue of William III, erected on

College Green in Dublin in 1701, and bombed in 1836 (beheading him) and in 1928

(doing away with most of the rest). This exhibition is the first to give Billy

his head back.

There is, too, a

portrait of Oliver Cromwell, which will be hung upside down by the Tate, in

keeping with the wishes of Prince Frederick Duleep Singh (1868–1926) to turn it

into a statement of heart-pounding monarchist politics. (Another difference

between vandalism and iconoclasm, our hosts pointed out, is that images must

remain recognizable if their, let’s call them, alterations are to have any real

political value.)

British School, "Portrait of Oliver Cromwell" (hung upside down); © Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

Never ones to miss a party, the Suffragettes are represented here by two paintings from a

series of thirteen attacked in Manchester galleries – Edward Burne-Jones’s “Sibylla

Delphica”, 1898, and G. F. Watts’s “May Prinsep (Prayer)”, 1867 – and one from

the National Portrait Gallery – John Singer Sargent’s “Portrait of Henry James”, 1913.

There is also a toffee hammer from 1911 used in the attacks (yes, really) as

well as the surveillance photographs issued by the Police to all museum

wardens, identifying the usual suspects. In the 1960s, the feminists took up

the mantle, if not the toffee hammer – throwing paint-stripper on Allen Jones’s

“Chair” (1969) and melting his lady's acrylic face.

Allen Jones's "Chair", 1969; Tate © Allen Jones

A third phase of

the exhibition considers how the Destruction

in Art Symposium (DIAS), which took place in London in 1966, made of breaking

and breakages an aesthetic

in their own right. Work by Yoko

Ono and Michael Landy will be joined by Ralph Ortiz’s “Piano Destruction”, which protested

against daily obliterations at home and abroad (specifically, Vietnam). One of a

series of public “destruction events” undertaken by him, it

will be displayed along with the BBC’s original audio recording of axe meeting

piano – which should make for a relaxing experience.

A final glimpse of the exhibition comes

in the form of “One Day You Will No Longer Be Loved II” (2008): one of a series

of historic portraits commissioned by the great and good, playfully doctored by

Jake and Dinos Chapman – the message being something along the lines of

“Thought your grandeur would last? Well, your portrait’s been sold (to us). And

you’re dead.”

Jake and Dinos Chapman, "One Day You Will No Longer Be Loved II" (No.6), 2008 © Jake and Dinos; Chapman Photo: Todd-White Art Photography; Courtesy White Cube

I can’t help but think, looking

again at the Mercers’ private collection, what fun the brothers could have in here . . . .

July 4, 2013

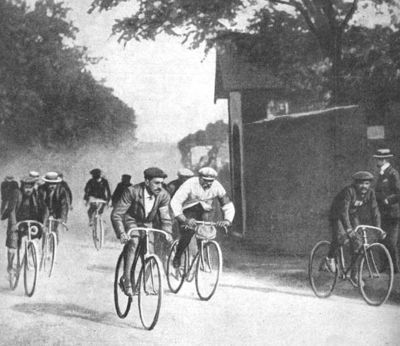

The 100th Tour de France

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The 100th Tour de

France (la Grande Boucle) hit the road last Saturday in the wake of the

decision to strip Lance Armstrong of his seven consecutive Tour triumphs (1999–2005)

for doping offences. In a rare interview with Le Monde, published last Saturday, Armstrong asserted that “it’s

impossible to win the Tour without doping”. The paper has always been a little

sceptical about Armstrong’s success; as if in retaliation, he had only granted the

paper one previous interview (in 2003).

The Texan rider has always exuded an

air of arrogance and supreme self-confidence. He was a friend

of George W. Bush, although no supporter of the Iraq invasion of 2003; he

drank beer rather than wine; spoke poor French; and generally did little to

ingratiate himself with the Tour authorities. Perversely perhaps, it was hard not to like him. And

then there was the remarkable story of his recovery from testicular cancer,

described in his high-octane autobiography It’s

Not About the Bike. Armstrong’s downfall and disgrace were shocking

in their totality, even if there was an inevitability about the process – like

watching a car crash in slow motion. But the Monde interview shows him largely unrepentant and bearing more than

a hint of scapegoat syndrome.

The most recent Grande Boucle visited

Corsica for the first time in its history for the first three stages, which is

pretty extraordinary given that the three-week race makes regular raids into

Belgium, Switzerland and even England (where it’s due next year: Sheffield).

Corsica seems made for the event: mountain roads, searing heat and spectacular

scenery. Insuperable logistical challenges have been cited as the reason for

the oversight up till now. Let’s hope it returns there soon.

According to a recent opinion poll

conducted in France, 40 per cent of French people are indifferent as to whether

the Tour continues or not; it is said to have lost sporting credibility. Le Monde, which has always given

extensive coverage to the event, this week had successive headlines of “Once

again there are doubts as the Tour gets under way” and “The peloton . . . wants

to escape from its past”. The past being 15 years of flagrant doping – several winners beside Armstrong have been stripped of their laurels – but one that goes back further too.

When, in 1967, the British rider Tom

Simpson collapsed and died on Mont Ventoux (the Bald mountain) in temperatures

of 35C, the autopsy revealed traces of amphetamine in his blood. At the time,

water was forbidden during the race but Simpson was known to take brandy on

board – a lethal cocktail then. In Geoffrey Wheatcroft’s centenary History of the Tour de France (2003),

the author reproduces a quote from the French rider Jacques Anquetil in the

year of Simpson’s death: “You’d have to be an imbecile or a hypocrite to

imagine that a professional cyclist who rides 235 days a year can hold himself

together without stimulants”. This year’s race will be visiting Mont Ventoux.

According to Wheatcroft, the mountain holds the record for “the strongest gust

of wind ever recorded on Earth”: 320 kph. It is desolate, intimidating and

majestic.

The most recent stage this year

(Wednesday the 3rd) took the riders from Cagnes-sur-Mer, near Nice,

to Marseille, a spectacular 228 km stage against a backdrop of massive

escarpments, past rust-red pine-clad rock formations and olive groves before

descending into France’s second city, on the approach to which the riders were

reaching speeds of 80 kph (50 mph): no time to admire the scenery; that’s left

for the TV viewer, who is extremely well catered for, even to the point of

being able to soak up views of the famous calanques,

or coves, between Marseille and Cassis (not strictly part of the route, but

breathtaking when seen from a helicopter camera out at sea). The Tour may be

all about roadside atmosphere – and there doesn’t appear to have been any

diminution in its popularity on the road – but anyone who has ever been will tell you

that the riders go past in a flash and it’s then all over. Alas, the sofa is

best in this case. To add to the pleasure, the stage was won by the British

rider Mark Cavendish, who now has a staggering 24 stage wins (the all-time

record, held by the Belgian Eddy Merckx, is 34). It surely won’t be his last

stage win this year.

July 3, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

There have been many great British art collectors, Angus Trumble writes in

this week’s TLS, but those seeking to discover exactly how many and how

great have often found obstacles in their path. Key-jangling housekeepers,

out-of-date inventories and minimal labelling all impeded those

investigating Britain’s collections in the centuries before public museums

opened our eyes to what was truly here. The story told in James

Stourton and Charles Sebag-Montefiore’s new book is as much about

shipping agents as it is about aesthetes. There was a lordly collector of

Van Dyck who owned “twelve whole-lengths, the two girls and six

half-lengths” without leaving any more information about what precisely

these paintings might have been and whether they genuinely were by Van Dyck.

There are many sad reminders of how much great art left Britain in the “sale

of the century” that followed the execution of Charles I.

In the four years in which Savonarola controlled Florence, any paintings that

depicted pagan scenes might be part of public fires, blazes of luxury goods

in city squares, perversions of the Italian carnival that were designed, as

Bernard Manzo explains, “to make anarchy itself subservient to Christ”. He

is reviewing Donald Weinstein’s “quizzical” biography of Savonarola, priest

of purity and penitence, a man who took on the Borgias, died in flames of

his own and left a legacy that is shared today among many shades of

Christianity and none.

Rooms in art galleries are normally rectangular. Peter Thonemann this week

cites a Soviet city planner who used to link private ownership to

right-angled walls and circular structures to Communism. Thonemann notes the

lack of angles in pastoral societies and the steep decline in British

roundhouses after the Roman invasion. But he is not sure that a preference

for round buildings reflects “a

fundamentally more egalitarian mindset”.

Stanley Weintraub describes how Bernard Shaw came to write less about art

galleries and, under the byline Corno di Bassetto, more about music.

Peter Stothard

Miss Evelyn Waugh

By MICHAEL CAINES

A brief review of a Brief Life in this week's TLS (Violet Hudson's short piece about Michael Barber's Evelyn Waugh biography) is all the excuse I need to repeat an old TLS story. This one, I think, is up there with the classic "Lit Supp" dismissal of one of its own contributors, T. S. Eliot:

Both Derwent May, in his centenary history of the TLS, and Selina Hastings in her Waugh biography record how, in 1928, the paper reviewed Waugh's first book, on Rossetti. The reviewer was the poet and artist T. Sturge Moore (writing anonymously, of course), who fell into the trap of thinking that an "Evelyn" could only be a woman – a woman who didn't know as much about art as he did.

"Miss Waugh", Moore declared, "approaches the 'squalid' Rossetti like some dainty Miss of the sixties bringing the Italian organ-grinder a penny . . . . Though alert and courageous, she surely sees but half, and is more inadequate over the poetry than the pictures."

Miss Waugh wasn't so inadequate that "she" couldn't respond with a letter, which was published the following week:

"My Christian name, I know, is occasionally regarded by people of limited social experience as belonging exclusively to one or other sex; but it is unnecessary to go further into my book than the paragraph charitably placed inside the wrapper for the guidance of unleisured critics, to find my name with its correct prefix of 'Mr,' Surely some such investigation might in merest courtesy have been taken before your reviewer tumbled into print with such phrases as 'a Miss of the Sixties.' . . ."

Hastings calls this a "small masterpiece of comic offensiveness", and quotes Rebecca West cheering Waugh on: "your letter to the Times Lit. Sup. . . . was a model of how one might behave to that swollen-headed Parish Magazine".

Matters did not immediately improve. The mistake about Waugh's sex was repeated the following year; the paper apologised. Then Waugh's own publishers, Chapman & Hall, presumably trying to make up for the fact that the TLS hadn't deigned to review Vile Bodies, took out an advertisement for it – only to describe it as "Vile Bodies by ALEC WAUGH" – ie, Miss Waugh's then more popular brother. Now it was Chapman & Hall's turn to apologise. It is not clear whether Rebecca West's opinion of the paper changed when it rejected one of her cherished poems, submitted for publication under a pseudonym.

After that, May says, things did improve, no doubt helped in part by some appreciative reviews and the appointment of Miss Waugh's friend Alan Pryce-Jones as Editor in 1948. (This earlier letter perhaps suggests one reason why Pryce-Jones didn't ask Miss Waugh to write for him.) And a few years later, Rebecca West was to become an occasional contributor to her Parish Magazine. T. Sturge Moore continued to write for the Lit Supp, after 1928, presumably checking carefully inside the book wrappers for the correct honorific each time he opened a book.

And we're left with the curious image of an "alert and courageous" Evelyn tentatively going up to tip the squalid Rossetti, the "Italian organ-grinder", as he churns out a tune on a Victorian street corner.

June 28, 2013

Aristo?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The French don’t have an aristocracy, right? It was bloodily consigned

to history, along with the French monarchy, during the Revolution, wasn’t it?

Well, not quite. Leaving aside the fact that Napoleon declared himself Emperor

in 1804 – was the Revolution really intended to lead to that? – the Restoration

of the Bourbons and the Bourbon-Orleans monarchy in 1814 took things up to 1848

and as if that wasn’t enough Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire lasted from 1852 to

1870. Only in that year did France embark on its succession of Republics,

interrupted by the Second World War, Marshal Pétain and Vichy.

There certainly was a cull of the nobility, and those who survived lost

certain rights and privileges; some went abroad, leaving their estates in capable

hands, and returned when conditions were more propitious. Others adapted to the

changed circumstances. Think of Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, who

served under the ancien régime, was President of the National Assembly during

the Revolution and held various senior diplomatic posts under the Directoire,

the Empire, Restoration, July Monarchy. Others still retreated to their

chateaux and kept their heads down.

To take one prominent public figure today, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing,

centre-right President of France from 1974 to 1981, and now one of the forty

“Immortals” in the Académie française, comes from minor nobility – the “d’” in his name was clearly no hindrance to his getting elected.

Valentine de Ganay doesn’t go into details of her family’s history in her entertaining book Aristo?,

which her publishers JC Lattès characterize as “un essai de sociologie

subjective”, but it appears to originate from Burgundy in the 14th

century. Ganay claims that the aristocracy in France is “no longer a social

class”. She’s certainly irreverent about those with social pretensions today,

referring to people as Machin de Machin (Thingummy of Thingummy). It’s not her

fault that her mother’s full name is Philippine de Noailles de Mouchy de Poix

de Ganay – a name she has been known to use, such as when she broke down on the

autoroute and gave her name to the breakdown man: “C’est français, ça?!” was

his reply.

Philippine would have liked to spend time on yachts or in Venice,

but she married a gentleman farmer who preferred to spend the second half of

August in Scotland shooting grouse (and who once took Valentine to Patagonia to

try to teach her to shoot deer). They have a chateau, Courances, 70 km south of

Paris near Fontainebleau, where Valentine stages events and whose grounds are

open to the public.

Valentine (below), much the youngest of four sisters, came as a disappointment

to her father, who was hoping for an heir. But Valentine, as well as being a

trapeze artist, horticulturalist and mother, is clearly the most

independent-minded of the four: when, in answer to a question from her father, she

reveals that she voted for Giscard’s successor François Mitterrand in 1981 (her

first opportunity to exercise her democratic right), he is physically sick, and

dismisses her from his presence. Later Mitterrand requests an invitation to

Courances, where Valentine’s father greets him in a strictly official capacity

(in his role as mayor): “Mitterrand and he will never be pals”. She lets slip

that they never received a thank-you letter from the Elysée Palace.

Another public figure who dropped in was Prince Charles - “’Guess who’s

invited himself to stay?’ our mother asks us.” Ganay reveals that he asked for

his breakfast to be brought up to his room.

When Valentine breaks the news to her parents of her engagement she

receives the following reaction (from her mother): “Je vous avouerais que je

m’attendais à un comportement moins conventionnel de votre part” – notice the

formal vouvoiement from mother to

daughter – at what point in their relationship, one wonders, did the mother

switch from “tu” to “vous”.

Her father has an office that overlooks the National Assembly and the

Place de la Concorde, in a building that once housed “the prestigious Club de

la Pomme de Terre”. Ganay tells us that a painting that represents several

members of that club has recently been acquired by the Musée d’Orsay; it

includes two members of the Ganay family as well as Charles Haas, one of the

models for Proust’s Charles Swann.

Proust’s novel is of course awash with aristocrats: Mme de Villeparisis,

M. and Mme de Guermantes (duke and duchess) and M. de Charlus (baron) among many others; the

narrator Marcel is at the same time fascinated by a cast to which he will never

belong, its rituals, traditions and eccentricities, and contemptuous

of its philistinism and its unthinking callousness to outsiders. And they

provide rich material for comedy, as in the scene in Du côté de chez Swann at a musical soirée at the marquise (mais bien sûr) de Saint-Euverte, where

Marcel compares the style of monocle worn by the various aristos, all doubtless

members of the Jockey Club – “le Jockey”.

I find the little snippets Ganay dispenses fascinating: when her sister

organizes weekend parties at her chateau in the Vendée, she insists on the

announcement “La comtesse est servie” whereas her mother prefers “Le déjeuner

est servi”. She points out that her mother doesn’t particularly want to be laid

out on a silver salver with parsley sticking out of her ears.

And when Valentine confesses to her parents that she has had an

affair with “L’Autre” shortly before the day of her wedding, which is to be

lavishly celebrated at Courances, her father tells her that she has “les moeurs

d’une femme de chambre” (as it happens, Le

journal d’une femme de chambre by Octave Mirbeau is one of her favourite

novels). The wedding to German artist Franck goes ahead, and the

union appears to have endured.

Ganay concludes by saying that “some aristos will reproach me with

having overdone it . . .”, but the rest of us should be thankful to her for so

revealingly, and stylishly, opening a window onto her world.

June 26, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

Bad English kings were rich, the good ones poor. Such a conclusion, familiar

and almost comforting to those anxious about our modern world, seems still

somewhat unexpected for the Middle Ages. This week Chris Given-Wilson

reviews the first edited and published account of “bad king” Richard II’s

treasure, an inventory on a 28-metre parchment roll in the National

Archives. Visitors to the Tower of London can be forgiven for forming the

impression that our royal collection of crowns and orbs dates back to the

misty origins of England. Of the 2,300 items listed in 1399, only one

survives, a handsome crown that is on display in Munich, a piece valued at a

mere £246 at the time when Richard’s “great crown” was worth £33,584.

Richard II was a greedy hoarder of wealth until he was murdered by an heir

whom he had dispossessed. So was Edward II, another little-lamented monarch

whose death by red-hot poker was discussed in a recent issue of the TLS.

Those “good kings”, Edward I, Edward III and Henry V, died deeply in debt.

That cheap surviving £246 crown was quite good enough for queens, a

gender-based distinction in wealth that has taken many centuries to lessen

in any serious way. Paul Seabright reviews two new books about women and

power in the modern workplace, covering education, ambition, the conditions

for dispensing with feminism and the relationship (inverse, it seems)

between early sex and career success. One of them, by the Facebook Chief

Executive Officer, Sheryl Sandberg, has attracted much more attention than

the other, by Alison Wolf. Seabright believes that readers in years to come

may give them the opposite priority. Sandberg’s advice is peculiarly weak on

irony and seems directed only at women who want to be like her, or to have

children like her, ideally both.

Frances Wilson, reviewing Judith Mackrell’s “sober and sure-footed” Flappers,

notes the similar female predicaments of Zelda Fitzgerald and Dorothy

Wordsworth. “Each had her sensibility plundered to enrich the writing of the

man she loved.”

Peter Stothard

Passport tourism

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

My younger daughter has just had her biometric passport, or e-passport, renewed, complete with electronic chip. “It meets standards set by the International Civil Aviation Organisation.” The personal details and photograph now appear at the front rather than back. On the inside leaf, below the royal coat of arms and injunction – “Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State Requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford the bearer such assistance and protection as may be necessary” – is an image of a picturesque terrace of houses, maybe in the Slaughters in the Cotswolds.

On the following 31 pages are “intricate designs and complex watermarks”, ready to be besmirched by visa stamps . They are adorned with traditional images of natural phenomena - “Reedbed” (see below), “Geological Formation”, “Shingle”, “Beach”, “Woodland”, “Moorland” -

and man-made ones: “Village Green” (below), “Canal”, “Fishing Village”. There are also “Mountain” and “Lake”, not features these islands are over-endowed with. In the top corner appears a cloud or sun of the kind we see on weather charts; realistically, unbroken sunshine is absent. But also absent are any representations of towns and cities, as are roads, motorways, ports, shopping centres, commercial parks, sporting arenas, etc.

This is a National Trust version of the nation that is being peddled. Far from unpleasant of course, but whom is it aimed at? Not the passport holders themselves presumably. Maybe the immigration officials who will be stamping those visas into the passport.

June 24, 2013

Because the night belongs to us

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Half-way

through Friday evening at the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room, Patti Smith

interrupted her flow of song, memoir extract, song, poem, song, with: “Any

questions?” The audience didn’t respond. Patti Smith commented that when it was

silent after she asked the same question at an Italian press conference a few

years ago – possibly also because her vocabulary was limited to “ciao” and “super

marcato” – she walked out.

Someone

suddenly shouted, “Is there anything in your life that you still want to do?” “No,

I’m done”, she replied, with deadpan humour. And then continued, “Come on, have

you been to a library? Look how many books there are you or I haven’t read.

There are a million things I want to do. I love being alive. The thing I most

dread is being run over by a Volkswagen before I’ve done my masterpiece. So I just

avoid Volkswagens.”

For

Patti Smith to suggest she has not yet made her masterpiece is humble – the

show, which was part of the Southbank’s annual Meltdown Festival (guest curated

by Yoko Ono this year), sold out immediately. Like me, the rest of Friday’s audience

was not prepared for a genuine dialogue with the punk musician and writer

(her memoir, Just Kids, about her

relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe, won the National Book Award

for nonfiction in 2010). But then this was no usual gig. The Purcell Room, modest and comfortable, complemented the mixture of reading and singing with her

acoustic band, which consisted of her son, Jackson Smith, on guitar, and her

daughter, Jesse Paris, on keys (both played well). “Don’t try to show me up”,

Patti Smith joked to them at the beginning, “remember, I’ve got the upper hand,

I changed both their diapers.” Affectionate exchanges like this happened on

stage throughout the night.

Her

first few songs were mellow with a blues feel, and chosen from later albums

such as Gone Again (1996), Gung Ho (2000) and Trampin’ (2004). In “My Blakean Year”, Smith’s crescendo

foot-tapping revelled in the song’s incantatory reference to William Blake’s poem “The

Divine Image”. Her infectious energy moved the song from melodious ballad to

characteristic grittiness; and from then on, she chose songs with bite. Defiant

fists punching the air, she sang the refrain from “Ghost Dance” (1978): “we

shall live again / we shall live again / shake out the ghost dance”.

We heard

a selection of poems, mostly taken from Smith’s poetic memoir Woolgathering (1992), with the same punctuated

rhythm and intonation as her songs (and, often, her speech) – this

cross-over meant Smith’s formal reading neatly drifted into ad lib “little

memories” and additions. The poem “Art in Heaven” included lyrical refrains,

“all you need is a helping hand to be lifted, lifted” and “I dreamed of being a

missionary / I dreamed of being a mercenary”. “Cowboy Truth”, dedicated to her long-standing friend and former lover Sam Shepard, ends with enigmatic, spiritual

imagery blended with a song-writer’s ear: “You are not forgotten, that is his

word, / his one great truth as he re-enacts the rituals of youth. / Putting

things right, just a dusty piece of humanity, / heaven’s hired hand.” Smith

introduced this with an anecdote about her second encounter with Shepard

in 1970, which cemented their friendship. She had stolen two beef steaks from a

New York shop (she was suffering from anaemia at the time but couldn’t afford

to buy red meat) and bumped into Shepard on her way home. After some time

talking, Smith told him she had to leave because she had two steaks in her

pocket that were melting. He didn’t believe her, stuck his hands into her

pockets and encountered the thawing meat. “For the next three months, he bought

me a steak each day.”

When it

came to “Because the Night” (co-written with Bruce Springsteen), Smith mucked

up her first verse entry with a burst of laughter. “Well it’s my only hit song

so I’ve got to draw it out.” Beginning again, she delivered her second attempt magnificently.

The

encore included a reworked version of “Banga”, the title track from her most

recent album, named after the dog in The Master and Margarita.

We were encouraged to join in with our own howls and barks, and Smith inserted new

spoken material between the verses, “this talking cat caused a riot, a

sweet riot . . . ” – a show of support, continuing her notorious political activism, for the Russian group Pussy Riot, following their "Punk Prayer" protest against Putin in February last year.

Because

Smith (and her family) created a unique atmosphere, it felt like the night did

belong to us.

June 20, 2013

Is it all over for Cork Street?

By ANNA VAUX

Is it all over for Cork Street? Back in the day, the annual summer party was something of a crush. The galleries opened their doors and the street was closed off at either end. Security guards patrolled to keep out the gatecrashers who would look down at the glittering scene and wanted to be where it was happening.

But there were no barriers or guards last night, let alone any gatecrashers. Anyone could walk by. I thought for a moment I must have the wrong date as I stepped out of Burlington Arcade and looked across the way to Cork Street, down which shiny cars were moving slowly but where I could see no crowd – or not much of one. A few people had gathered outside the beaux arts gallery, but then, the beaux arts gallery was serving wine, and last night was 28 degrees in central London, the warmest night in nine months, I heard when I got home.

I saw wine at the Bernard Jacobson Gallery, but only a couple of glasses behind the desk, and the smiling assistant told me that it was just for the staff – to keep them going, he said, as though the evening were something of an ordeal – in spite of the gallery being virtually empty, and that in spite of the fact that it had the most beautiful exhibition in the street, of Robert Motherwell collages.

There were also some exceptionally beautiful pictures by Agnes Martin across the road, in the Mayor Gallery at 22a – in a show together with five other women artists called "The Nature of Women" – but it wasn’t as though I had to compete with any other viewers. I had those small perfect works almost to myself and could have stood as long as I liked in front of them – or would have done, except that they turned off the lights.

Waddington, across the road at number 11, was closed altogether. I could only look at the Patrick Caulfields through the window, and was distracted in any case by the cleaner who sombrely pushed a vacuum across the wide open empty space.

Perhaps everybody was round the corner at Sotheby’s, which last night had a large ticketed sale of Impressionist and modern art. Or they were too exhausted after the Basle-Venice roadshow. Or they were saving themselves for Vyner Street Thursday, when the dozens of galleries in the cobbled backstreet by Regent’s canal, at the end of Broadway Market in East London, open on the first Thursday of every month. Or they were thinking of visiting Gagosian in King’s Cross, or White Cube in Bermondsey, or Saatchi’s in Chelsea, or any one of the thirty-odd galleries that have opened up in Fitzrovia, which, like Vyner Street, might now be said to be one of the new centres of commercial art in London.

But wherever it is, it’s not Cork Street. Westminster Council has plans to develop the street, and as I stood there fanning myself in the sultry heat with a piece of card advertising Bernard Cohen’s exciting exhibition at Flowers, it was pointed out to me that five galleries north of that show will be demolished in the autumn. Another large chunk of buildings on the other side will be demolished next year. Nor does it seem there was much protest against the development. Few, I was told, turned up at the party organized to register unhappiness about the council’s plans, and the gallerist I spoke to was sanguine about having to move. He’d get a bigger space, he thought. He doesn't want to hang around where nobody else wants to be any more.

This year will also be the last Cork Street Open – an exhibition which has run for the past five years, providing an opportunity for new and established artists to complete to show their work, a kind of Cork Street version of the RA summer show. “Due to other business commitments and changes with the premises a decision has been taken to make this summer show the last”. The final exhibition will run from August 9 to 16. Catch it while you can.

June 19, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

The philosopher Anthony Kenny, one of the clearest modern writers to wrestle

with the difficulties of Christian belief, this week considers the religious

warfare within the work of C. S. Lewis. Reviewing a new biography of the

author of the Narnia stories, he praises its careful correction of many

previous accounts, that by Lewis himself being the one “most in need of

emendation”. He notes the argument over whether Elizabeth Anscombe, a more

formidable Christian philosopher than Lewis by far, was rewarded for her

ferocity by a characterization as the White Witch. Nowadays, Lewis’s

theological works “preach mainly to the converted”.

Battles between Christian and pagan were no less fiercely fought among the

ancient commentators on Aristotle. David Sedley praises the ninety-ninth

volume of a massive project of the past twenty-five years to translate into

English all the scholarship of such men as Simplicius and John Philoponus,

great scholars with an immense armoury of scorn and “derogatory epithets”.

Volume Ninety-nine concerns the offence to Christian doctrine caused by

eighteen different fifth-century arguments for the world’s having no

beginning and no end.

Oscar Wilde’s interest in ancient philosophy is familiarly described in terms of

“Plato and sexual intimacy between men”, writes Joseph Bristow, reviewing a

new study by Iain Ross. The influence of Wilde’s archaeologist father is

often neglected. The playwright had a very “advanced classical education”,

and was deeply imbued with the conflict between the new archaeology and more

traditional textual criticism. In extending the feuds of scholars into The

Picture of Dorian Gray the author, however, goes a little too far.

There has been no more potent explosion of Christianity and paganism in the

modern age than Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, described by

the composer’s friend Robert Craft in a centenary appreciation as “the image

of God as expressed in the primitivism of pagan Russia”. Craft interprets

Stravinsky’s own faint pencilled instructions on how the work should be

danced.

Peter Stothard

NB Take part in the TLS Reader Survey and win £50 in Amazon.co.uk Gift Certificates (UK & ROI only).

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers