Peter Stothard's Blog, page 62

May 1, 2013

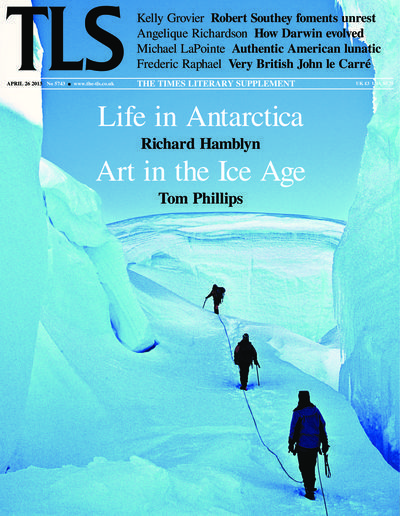

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Deputy Editor

The circumstances of Marc Blitzstein’s murder at the hands of three merchant seamen in Martinique in 1964 remain mysterious, while his musical legacy remains in limbo, with much of the music he composed virtually forgotten, unpublished and unrecorded. Homosexual, charming and irascible, described by Orson Welles as “fine-tuned rather than highly strung”, Blitzstein enjoyed the good life but devoted himself to employing “the sophisticated resources of modernist art music in the service of ‘the People’ – no easy task”, writes David Schiff, reviewing a “massive new study” which fills in some of the gaps left by earlier scholars. Is Blitzstein still paying the price for his communist beliefs and adherence to the Party line, or do those beliefs “continue to give the music a critical aura it may not deserve”? Blitzstein, we are told, “suffered to some extent from depression and alcoholism, but then again so did Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald”. And so did Charles Newman, the novelist, editor, essayist and dog-breeder whose magnum opus remained unfinished at his death in 2006. Douglas Field reviews a volume that offers “a tantalizing glimpse” of Newman’s folie de grandeur.

The folie Sainte-Beuve attributed to Charles Baudelaire was somewhat different: both an exotic folly, “highly decorated, highly tormented . . . where people recite exquisite sonnets [and] intoxicate themselves with hashish, where they take opium and thousands of other abominable drugs”, and a form of madness. Lauren Elkin reviews a study of Baudelaire, the “ambivalent philosopher of modernity as well as its exemplar”, by Roberto Calasso. Samuel Johnson, himself tormented by depression and fear of madness, found “through the balancing of alternative propositions in a single sentence” a pathway to sanity, writes Kate Chisholm, reviewing two new books – one of which offers a very twenty-first-century Johnson, much concerned with vegetarian diets and the benefits of exercise.

Alan Jenkins

Project Colony

By TOBY LICHTIG

"Are you here

for the party?", asks the girl.

She's wearing red

lipstick, a summer frock and an expression of benign wonderment. We tell her we

are.

"Oh

good!" she cries, clapping her hands. "We're so excited!"

We've arrived at The Colony, the penal settlement of Kafka's

imagination, now relocated to Trinity Buoy Wharf, just opposite the Millennium Dome, on the north bank of the

Thames. This place is rich in London

history; it is the site of the city's only lighthouse, as well as the former

workplace of Michael Faraday. Tonight, however, the wharf has become a faraway

British outpost, its development arrested at some point in the 1950s.There are

around eighty other guests and twenty wide-eyed natives.

"We've never left the island", one girl confides to

us. "Our parents used to tell us all about life in England."

We're led to a former chain warehouse, kitted out with balloons,

a stage, a bar and round tables. Locals chat to us. One mentions that times

have changed. Things are looking up. The former Commandant of The Colony was

not a nice man. But his replacement is kinder. He wears a striped shirt,

a thin moustache and has the air of a hotelier at a British postwar seaside resort.

We sit down and have a drink.

Suddenly the mood changes. Several more locals arrive, dressed in white shirts and braces, silent and

menacing; they beckon for a group of us to leave. We're led out,

along the wharf, the City of London glimmering in the charcoally pink dusk, and

down a flight of stairs to a dark basement, where an ominous torture contraption lies

in the centre of the room. We take our seats and watch on as a weary traveller,

dragging a wheely case, is introduced by an army officer to the mechanics of

the elaborate apparatus. In the corner, an uncomprehending prisoner

awaits her just deserts.

Fourth Monkey’s Project Colony is an innovative reworking of Kafka's 1914 short story

"In the Penal Colony", and an excellent evening out. The basement

play itself is an impressive dramatization of the text, but what makes the

event so compelling is the theme of complicity that it teases out. We are both

revellers and spectators, audience and participants, drawn into the

action. Like Kafka’s “explorer”, we are encouraged to question our role as tourist

or agent of change. As the explorer comments in the original story: “It was

always a ticklish matter to intervene decisively in other people’s affairs”.

After the first part of the play – which ends with a strap

breaking off the device, much to the chagrin of the eager executioner – we are

led back upstairs, swapping places with another group of guests. We have some more

drinks and play a game of pick-up sticks. There are lollipops for the winners

and then a quiz. A band plays a couple of songs.

Later, we are rejoined by everyone from the basement, including

the other half of the audience. Kafka’s sinister tale resumes. The

officer must come to terms with the obsolescence of his mechanism and the

inhabitants of the colony are confronted with the results of their inertia.

Even if the play becomes rather baggy at this point, with several inadvisable interpretative liberties, and the acting isn’t quite

first-rate (shouting seems to be an all-too-ready

substitute for projecting), our role as uncomfortable witnesses is emphatically

underlined. With an audience-cast ratio of 3–1, we are pleasingly

immersed by the drama. We are strangers in a strange land, unsure of our

function, stuck somewhere between a party and a nightmare.

April 29, 2013

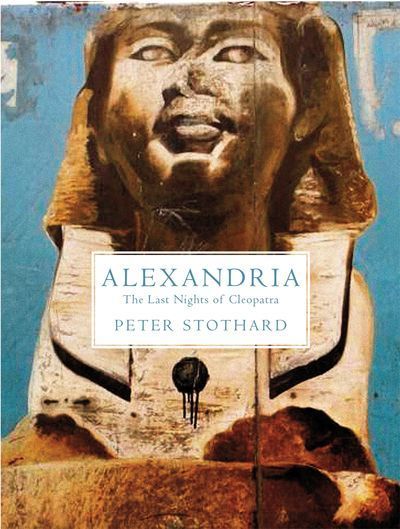

Alexandria: The Last Nights of Cleopatra, at Fowey and Hay on Wye

BY PETER STOTHARD

In December 2010 I felt suddenly frustrated at a long-time failure to write a book about Cleopatra -and took off to Alexandria to see if I could better complete it in the city where once she had ruled.

The onset of the Arab Spring became just one of the obstacles that freshly complicated the task. My daily diary entries became as much memoir of dead and living friends as history of a dead queen.

That diary is now Alexandria: the Last Nights of Cleopatra, a book, even if not quite the book I long intended. It is about to be published by Granta and its first outings are at the Du Maurier Festival at Fowey on May 12 and at Hay on Wye on May 26.

It would be wonderful to find there some festival-going TLS readers and Facebook friends.

April 26, 2013

Muriel Spark makes the case for abridgement

By MICHAEL CAINES

“Complete and unabridged” – the reassuring phrase isn’t deployed by publishers now as often as it once was. Drastically abridged editions of classic novels were once a staple part of the book business, going back, as far as England is concerned, to at least the early eighteenth century.

(For example: the Bancroft Books series for children, with their nostalgia-inspiring covers, manages to reduce the length of Ivanhoe by about 300 pages.)

In the midst of such contrivances, discerning readers could be flattered with the prospect of the real McCoy. Hence Sidney Lee’s deployment of a powerful word – “pure” – to describe the unabridged, complete “Universal Library” he edited for Methuen. One wonders what he would have made of the later habit of abridging, say, Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde. It’s hardly a door-stopper, but you can imagine a medieval poem inspired by the Trojan War daunting English literature undergraduates for other reasons, and OUP et al astutely taking note of this abridgement-sized gap in the market.

In contrast to the Sidney Lee mode of textual idealism, consider the curious case of The Last Man.

In this week’s TLS, Kathryn Hughes reviews the (latest) reissue of Muriel Spark’s “critical biography” of Mary Shelley, first published in 1951. At the back of the book is an appendix. Thirty-two pages long, its opening paragraphs outline the state of things to come before giving way to indented quotations set in smaller type – quotations of only a few lines at first, which soon grow to fill whole pages. The appendix ends with the lines that furnish the novel with its title:

“Thus around the shores of deserted earth, while the sun is high and the moon waxes or wanes, angels, the spirits of the dead, and the ever-open eye of the Supreme, will behold the tiny bark, freighted with Verney – the LAST MAN.”

This is, of course, an abridgement of Mary Shelley’s third novel, The Last Man (1826), and Spark justifies her apparent act of literary heresy on practical grounds.

By her reckoning, Shelley’s original is around 170,000 words long. It’s “almost unknown” to the general public, and is “unobtainable except in very rare editions”. In an earlier chapter devoted to it, she concedes the novel has its faults, but concludes by comparing it to Frankenstein and calling it “wonderful”.

The appendix seeks to support that point. Suspecting that The Last Man “will hold a more pertinent appeal for present-day readers than it did even in Mary’s time”, Spark offers her “utilitarian” version of it in the hope that “wider recognition of its merits may lead to its being reprinted”. (To translate for the internet age: she's uploaded as much data as she can, but doesn't have sufficient bandwidth to upload the whole thing. Hence the abridgement.)

Fourteen years later, the University of Nebraska Press obliged, and their example was followed, some decades on, by Oxford World’s Classics and Broadview Press (overwhelmed with excitement, confused by this copiousness, Amazon currently prints praise for Broadview next to the Oxford edition).

And now The Last Man is available on Open Library, Project Gutenberg etc. So in this instance the practical case for abridgement seems to have disappeared.

What remains is the point that Spark’s eloquent chapter on The Last Man and the abridgement make good, complementary companions. You could do worse than enjoy the later novelist’s appreciation of her predecessor’s work while testing your reactions to Shelley’s prose, via the abridged Last Man.

And: to remove the appendix now would be to abridge Spark’s book . . . as it is, its original title, Child of Light, is long gone.

April 25, 2013

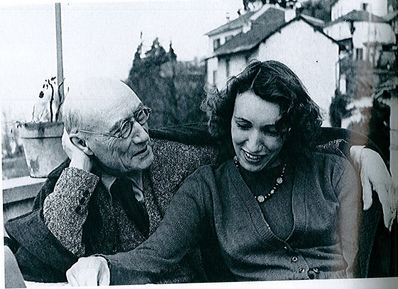

André Gide and Catherine Gide

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Catherine Gide, the daughter of André Gide, and probably the

last surviving link to early-twentieth-century French literature, has died at

the age of ninety. Some will no doubt be surprised to read that the writer, who

made his homosexuality public, had a daughter at all (she was his only child).

Catherine was born in 1923, when Gide was in his early fifties.

Gide had married his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux in 1895. In

his autobiography Si le grain ne meurt, Gide wrote "Mon amour pour celle

que j'avais décidé d'épouser me persuadait de ceci: qu'elle avait besoin de

moi, si moi je n'avais pas besoin d'elle, de moi spécialement, pour être

heureuse" (My love for the woman I had decided to marry convinced me of

this: that she had need of me, even if I had no need of her, of me specially

in order to be happy). As is so often the case when Gide writes about himself (and

he did so a great deal), it results in questionable sentiments beautifully

expressed – carefully calculated self-revelation dressed up as naked

confession.

The (unhappy) marriage was unconsummated and it was in the

early stages of it that Gide properly discovered his homosexuality – an

awakening that led to books such as L'Immoraliste and Les Nourritures

terrestres. He took up with the very much younger Marc Allégret, the son of a

family friend and later a filmmaker, with whom he travelled widely, including

to the Congo: Gide's Voyage au Congo, in which he denounced the brutality of

Belgian colonialism, is one of his best books.

The relationship that produced Catherine was with Élisabeth

("Beth") Van Rysselberghe, the daughter of the Belgian painter Théo Van

Rysselberghe, who was a friend of the writer. Théo's wife Maria was one of

Gide's closest confidants. Élisabeth had been Rupert Brooke's lover. She

travelled frequently in company with Gide and Allégret. And brought up their

daughter.

André Gide with his daughter Catherine Lambert, Lake Maggiore, 1947

In his fine biography of the writer (1998), Alan Sheridan

relates how Gide gave Catherine her first piano lesson when when she was six

and how he would read to her from the 1,001 Nights.

According to Sheridan, Gide had to adopt Catherine when, in

1938, he sought to have her recognized officially as his daughter – "because she was the child of an adulterous relationship, 'recognition'

would have no legal binding". It's clear from Sheridan's biography that

Gide held his daughter in great affection: "he had no wish to live with

her, but he wanted to be on hand, to supervise her progress and give her the

benefit of his tuition".

Again Sheridan: "Catherine interested Gide to the

extent that she showed a desire to be educated by him: the pedagogue/pederast

would make allowances for her sex. The eighteen-year-old Catherine was now a

jeune fille en fleur, one who showed no interest whatsoever in her father's

work and only perfunctorily in matters intellectual".

In his voluminous Journals (which Gide himself regarded as

his most lasting work), he writes on July 26, 1941: "I came away

delighted from Catherine's dancing class, which I have just attended". In

what must rank as one of the more inappropriate juxtapositions in print, he

goes on: "Were I a ballet-master, I should go and recruit on the beach

some of those little Italians (perhaps French boys) with tanned bodies whom I

was watching yesterday . . . and whose elegant and rhythmical way of swimming I

was admiring. Trained in dancing, they would seem so provocative that, out of

regard for public morals, no one would dare to 'produce' them".

Later, he writes, "I am rereading Genesis for

Catherine's intention" (one can picture the high-minded solemnity). And

then: "Catherine might have bound me to life; but she is interested only

in herself – and that does not interest me . . . . I had rejoiced immoderately

over those lessons I was preparing to give her in Nice . . . . All her time is

taken up with other lessons (dancing, singing , elocution), which merely

directs her attention to herself".

But Gide approved of her choice of marriage partner in 1946,

Jean Lambert, who, according to Sheridan, was "an academic specialist in

German and English".

Sheridan writes that when visited by Dr Delay in his

final days Gide lamented "I'm afraid that my sentences might become

grammatically incorrect" (Gide died in February 1951).

(What strikes one particularly from Sheridan's biography is

the staggering amount of movement in Gide's life, right up until his final

years – he never seems to have stayed in one place for long – from the early

years of vagabondage across North Africa to . . . "Gide and the Lamberts

then moved out to an hotel at Sorrento" . . . .)

Catherine became a true keeper of the flame for her father's

work, overseeing its appearance in the prestigious Pléiade series. In 2007 she

set up the Fondation Catherine Gide whose resources she made available to

writers and researchers (The Fondation have published a death notice in Le Monde for April 25).

She also wrote a foreword to the posthumous Le Ramier (woodpigeon), which was

published in 2002 and recounts a sexual encounter between the writer and a

young farm boy. She revealed that she had found among her father's papers

"a short erotic novella, dated 1907 and titled The Woodpigeon". Later

she writes "This short text is full of joie de vivre" – "Toute

perversité en est totalement absente".

April 24, 2013

In this week's TLS - A note from the Deputy Editor

Though the past few years have seen the super-injunction, a super-expensive means of ensuring that no newspaper can publish what someone would prefer not to be known, applied with increasing frequency, no one, to our knowledge, has recently brought an injunction against themselves. Yet this is just what Robert Southey did in 1817, in an attempt to prevent publication of a youthful folly – the play Wat Tyler, celebrating the Peasants’ Revolt and advocating political reform. Twenty-two years after it was written, the unpublished play had been conveniently forgotten, and Southey, by then Poet Laureate, was enjoying the fruits of a very different political stance. He was “aghast” to see an advertisement announcing the “inflammatory” play’s publication. Kelly Grovier, reviewing four volumes of Southey’s Later Poetical Works, uncovers the story of its missing years.

Richard Brautigan hitchhiked to San Francisco in 1956, intending to pursue poetry, but, out of step with the Beat movement – Allen Ginsberg called him “a neurotic creep” – he struggled to make a mark. Switching from verse to prose, he claimed “I don’t want to sit at the children’s table any more”, but it was with the Flower Children of the hippy movement that he found success. When they lost interest, he struggled again, this time against drink and adverse criticism, living “in a macho milieu of hard drinkers, gunslingers and philanderers” and eventually shooting himself with one of his beloved Smith & Wessons. Michael LaPointe, reviewing a biography that attempts the rehabilitation of Brautigan as a major American author, concludes he was more of an authentic American lunatic. While Brautigan liked to frighten hosts with his .357 Magnum, the poet Edward Dorn produced a magnum opus in Gunslinger, written over seven years from 1967. Dorn once expressed the view that poetry was “obsolete”, but a new Collected Poems reviewed by Jules Smith runs to almost 1,000 pages. His career went “without official honours” and, writes Smith, “he seemed content about that”.

Alan Jenkins

I’m A. N. L. Munby, I am . . .

By MICHAEL CAINES

Talking of conferences and innovations in typography: here's an unusual view of a bibliophile and sometime TLS contributor, the ingenious A. N. L. Munby, holding court. (More book historians should dress like Henry VIII, I say, or some other monarch.) I'm speaking at a centenary conference to be held in Munby's honour at King's College, Cambridge, where he was a Fellow and Librarian, at the end of June. The research has, so far, been nothing but a pleasure.

The conference website explains why Munby is such an important figure for the study of books, his activities ranging from downright collecting, cataloguing and lecturing, to surviving as a POW by writing ghost stories and co-founding the Cambridge Bibliographical Society. He wrote the five definitive volumes of Phillipps Studies, about the nineteenth century's most avid collector of manuscripts, and, just to be sure he'd made his mark, succeeded in persuading the scholarly world that booksellers and auction catalogues could be crucial resources, rather than negligible ephemera.

He himself could claim, in an essay of 1952 – "Floreat Bibliomania", from which the conference takes its name – to own some 1,500 sale catalogues, but counted this as a "very modest" figure: "the late Seymour de Ricci had 30,000 sale catalogues, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale". A postscript added some twenty years later confesses that the 1,500 had by then grown to about 7,000 "and will be a major worry to my executors".

Yet Munby knew the dangers of overdoing a good thing. To quote again from the superb collection Essays and Papers (you don't need to be a bibliomaniac, by the way, to savour Munby's prose):

"The will-power necessary to get rid of books must be maintained at all costs. Even if one buys on a modest scale – say, one book a day on an average . . . . I once visited a house in Blackheath after its owner had died. It was solid books. Shelves had been abandoned years before; in every room narrow lanes ran between books stacked from floor to ceiling, ninety per cent of them utterly inaccessible. In one of the bedrooms there was a narrow space two feet wide round the bed, and there the owner had died, almost entombed in print. . . ."

Bibliophile: consider yourself warned. Again.

Photo copyright the Estate of A. N. L. Munby.

April 22, 2013

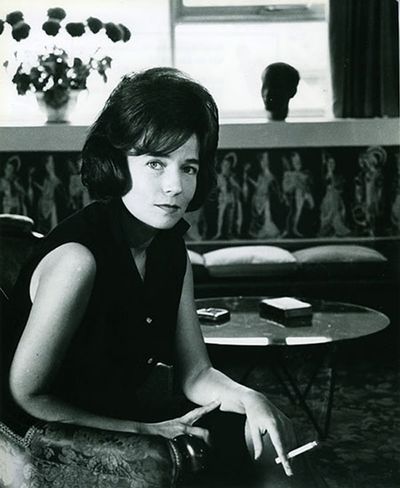

Celebrating Christine Brooke-Rose

By MICHAEL CAINES

Readers of the most recent TLS Poem of the Week will already know what Christine Brooke-Rose’s first contribution to the TLS was: “The Lunatic Fringe”, a poem published in 1956. She started reviewing for the paper a little later, and her first novel, The Languages of Love, appeared the following year.

In the 1960s, however, she set herself on a different course, with the books Out, Such, Between and Thru – an enthralling quartet subsequently republished as a bulky omnibus by Carcanet – with the predictable result of alienating anybody who didn’t care to put much intellectual effort into their reading. These were “language games” for those who liked their roman to be nouveau and their Joyce to be James not Cary. I’m not sure if it’s more a welcoming-in or a warning-off if I describe Xorandor, my current favourite, as a kind of computerized Compton-Burnett.

The Royal College of Art deserves great credit for hosting a symposium last week celebrating Brooke-Rose’s work. It was good to hear both Ali Smith and Tom McCarthy championing her, as well as the design expert Rick Poynor placing Thru in the context of twentieth-century innovations in typography and Natalie Ferris, the brains behind the operation, describing the shape of Brooke-Rose’s life and career, tracing the development of her “lexivore” mind.

Additional pleasures included a screening of the amusing Bookmark programme about Brooke-Rose (could the BBC produce such a good literary series today?), complete with a cameo from the rebarbative Margaret Thatcher at a summit meeting, and an interview with John Calder. Now in his eighties, Calder admitted that he couldn’t really remember his encounters with Brooke-Rose, but raged nonetheless against the conservatism of mid-century book reviewers who took against his kind of work, and hers, and slipped easily into stories from his publishing days: what happened when Beckett met Burroughs; how he kept Alexander Trocchi going (“he was a bit of a rogue . . . some writers are”). The dismissal of the current state of publishing as a “disaster” was balanced by the conviction that there will always be good new writers coming along.

I hope that the speakers’ enthusiasm persuaded anybody in the audience who hadn’t read at least one of those post-1960 novels to try them. The symposium left me with the impression that Brooke-Rose deserves a wider readership despite her off-putting reputation for “difficulty” – that question Edward Albee asks about Virginia Woolf comes to mind.

Is there any need to be afraid? Decide for yourself. Here’s a selection from that transformative quartet of novels mentioned above, beginning with the zoomed-in narrative of Out:

“A microscope might perhaps reveal animal ecstasy among the innumerable white globules in the circle of gruel, but only to the human mind behind the microscope. And besides, the fetching and the rigging up of a microscope, if one were available, would interrupt the globules. If, indeed, the gruel hadn’t been eaten by then, in which case a gastroscope would be more to the point. And a gastroscope at that juncture of the gruel’s journey would provoke nausea.”

Then there’s the astrophysics-inspired Such:

“The waves expand into a spiralling query from a small unstable nucleus of fear hidden like the square root of minus one deep inside the charm, the well-living swarthy flesh, the soft Levantine eyes and labyrinthine knowledge of law that makes up what you as a psychiatrist should know, I mean what happens to that thing you chaps call the unconscious when the body lies in the lowest state of life, if at all, well, they may put people on ice for years, I mean, what ought to happen, you must know the theory at least, does it tick on at a low imaginative level or what, did you dream, for instance?”

Brooke-Rose wrote Between without recourse to the verb “to be” (and it was published the year before Georges Perec’s lipogrammatic La Disparition, Friday’s symposium taught me):

“Inside [the plane] they have pressurized the comfort. The people sit hidden in their high armchairs but for a few head-tops bald fluffy blond curly back between the port and starboard engines, looked after cradled in their needs, eat drink smoke talk doze dream and didn’t catch what you said.”

And lastly, here’s what Thru can throw at you:

As well as:

There. Was that so bad?

There's another kind of difficulty, for the symposium's speakers and other readers: the critical one of knowing how best to place Brooke-Rose's work. She was, after all, a female academic working in Paris, trilingual by upbringing, wary of being grouped with either French or English contemporaries (the third language was German), in whose work classical influences may be felt at times more clearly than modernist ones, who grasped the expressive potential of typography in as-yet unequalled ways (see above), and wrote a ZBC of Ezra Pound. It's no surprise to see her being celebrated in an art college.

NB Here’s what Ali Smith had to say about the omnibus and a valedictory work, Life, End Of in the TLS a few years ago.

NB2 And here’s a coincidence: I’ve just been handed a review to edit of some of the reissued novels of B. S. Johnson, the innovative contemporary with whom Brooke-Rose is sometimes grouped. It appears that a “new genealogy” of English post-war fiction, hoped for by McCarthy, is already with us, if only we have eyes to see it .

April 20, 2013

'The ice-pick man cometh'

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This was the heading John Sturrock gave to a

TLS review of a biography of Leon Trotsky in the TLS some twenty years ago. The

heading was so good that I think he may have used it more than once -

perfectly reasonably; after all, if you've got a winner make the most of it.

I'm not sure how much readers of the TLS notice our headlines: their

eyes will be drawn to see what's being reviewed, and then to the first (or

last?) sentence. The headline is there, ostensibly to help of course, but it's also

an optional item. That said, a really good heading can steer the reader, or

encapsulate the reviewer's assessment of the book in a few words. Or it

can intrigue – and, on rare occasions, even amuse. But above all it shouldn't

mislead the reader (something of which I feel I’ve been occasionally guilty in giving

headings to letters published in the TLS).

I had a quick look at the first issues of the paper

(1902) to see how TLS editors approached headlining then – fairly austerely I’d

say: “The Duke of Devonshire’s pictures”, “Railway reading”, “Ecclesiastical

reprints”, “Mr Henry James’s new book”, “Automobilism and its literature” and

so on. “A German defence of British policy in South Africa” is particularly

snappy. Ditto “Sidelights on the Persian question”. But they’re certainly not

uninformative.

Skipping to the TLS for 1939, I see that quite a lot

of agricultural titles were reviewed, giving rise to headings such as “”A plan

for British agriculture” (Jan 39), “Towards better farming” and “British

farming” (July), as well as “Cameos from the farm” (Oct). As the book reviewed

under that last heading, Teamsman by Crichton Porteous, suggests, these publications

weren’t about making contingency plans for the coming crisis: “to avoid the

ruts Mr. Porteous seeks lodging away from the farm, studies in bed, reads

Thoreau behind his ploughing team, contributes fragments to country papers . .

.”.

But the global situation certainly wasn’t ignored elsewhere in the paper, and it’s gratifying to see, among the slew of reviews of books

on the Nazi threat (and a sober editorial in the issue of Sept 9 on the

importance of publishing books at such a time), a piece on October 14 headed “Why Nazi

Germany can’t win”. The book being reviewed, by the way, was Nazi Germany Can’t

Win by Dr Wilhelm Necker (see below).

A few decades on, in 1982, the TLS reviewed Jean-Jacques Beineix’s film

Diva, about a Paris dispatch rider on a moped who is obsessed with the diva

of the title. Lindsay Duguid, who was in charge of the Arts pages at the

time, headed the piece "La donna et Mobylette" - a

heading so good it has passed into what passes for TLS legend. (On the

same page there’s “Dearth of a salesman”.)

But generally I sense that giving headings to reviews unavoidably

involves a good deal of recycling. I wonder how many times we’ve used “Command

performances”, “Natural causes”, “Parallel perceptions”, “Exotic excursions”,

or “Selective affinities”. Maybe not as often as I suspect. Or, in a slightly

different mode, “Writing against oblivion”?

. . . Having said that, “Writing to hounds” for a review of a hunting

and shooting anthology of R. S. Surtees is very good.

The Letters page doesn’t give much scope for facetious heading

(thankfully), but a couple of years ago we published a review by David

Gallagher of Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel about the Irish nationalist Roger

Casement who, in Gallagher’s words, “served the British crown with loyalty, was

knighted in 1911, then hanged for treason five years later . . .”. There was

discussion of the Black Diaries, in which Casement is said to have kept a

detailed record of his homosexual activities in sub-Saharan Africa and South

America. We then ran a letter from Casement’s biographer Angus Mitchell

(January 14, 2011) in which he referred to the post-mortem carried out on

Casement’s body - the letter contained the unimprovable sentence “Fortunately,

a brief history of Casement’s anus can be collated from various medical records

and correspondences”. It was only after the issue had gone

to press that I thought of heading the letter "Riddle of the

sphincter". But I’m not sure it would have met with general approval.

April 19, 2013

The Shed at the National – it’s got legs

by Thea Lenarduzzi

The Shed at the National Theatre. Photograph: Helene Binet

It’s been compared to Battersea

Power Station, an Amish barn and “a giant's up-ended hen house” – and it’s only been around for three weeks. But the striking red structure jutting

from the side of the National Theatre is, officially, The Shed: a 225-seat

theatre erected to cover the year-long refurbishment of the Cottesloe Theatre.

The theatre, designed by

the architects at Haworth Tompkins, is intended by the National as an

opportunity “to take risks” on emerging writers and performers. The year’s

programme – which ranges from a piece devised by the New York based theatre company THE

TEAM (“Gertrude Stein meets MTV”) to an adaptation of Ross Collins’s children’s

book The Elephantom – opened on April 9 with Table, a new play by

Tanya Ronder, directed by Rufus Norris.

Ronder is perhaps best

known for her adaptations – including one of DBC Pierre's Vernon God Little in

2007 and another, of Peter Pan, in 2009 – but Table is a far, well, riskier

endeavour, based on three years’ worth of improvising, work-shopping and

writing. The result charts the events that shape six generations of the same

family, played out, as you might have guessed, around, on and under their hand-me-down

table.

Beginning in Lichfield

in 1898, with a furniture maker on his wedding night giving his table a final

polish, the play ends – and this is in no way a spoiler – in present day London,

via Tanganyika in the 1950s and a Herefordshire free-love commune in the 60s

and 70s.

The interest lies in how the Best family history – a miniaturization

of that of the twentieth-century, and the beginning of the twenty-first – has left its traces on the table: the

enlistment of an only son in the First World War (a long, deep scratch); a

bleached area (the urine of a repressed young man who dreams of studying

couture); scratches made by the claws of a leopard, and others by the nails of

an impulsive nun; “Amor Patris” carved on the inside leg by an absent father; the

burn from a stubbed out joint. Patterns emerge, births and deaths, celebrations

and bust ups, comings and goings…. And there are invisible marks, too – “the

tiny shards from 27 million boring conversations” and the flour from 5000 loaves of bread, for example.

Ronder’s is a

hopeful, and often humorous, play (the family surname and a character called

Hope are an opportunity for wordplay, readily taken – “Hope is with me”; “Do you have a

message for Hope?”, etc) – despite the threat of a replacement glass table from Ikea

(the assembling of which, I imagine, would occasion a few bust-ups of its own). The whole leaves one wondering:

at what point does a prop become an actor in its own right?

The centrality of

the piece of furniture has led some critics to compare The Shed itself to an

upside-down table (I have yet to try my theory of an upturned beheaded pig on

them), contributing to the general air of mischievous unpredictability that

surrounds the National’s new venture. Haworth Tompkins is no newcomer to

theatre redesigns or pop-ups developments, having revamped the Royal Court and Young Vic,

and built two temporary theatres for the Almeida. Let’s hope that this latest project – fighting red and clad in rough-sawn timber boards intended, by the architects, as

the “opposite” of Denys Lasdun's board-formed concrete building – proves as

rebellious as first appearances suggest . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers