Peter Stothard's Blog, page 65

March 8, 2013

Untranslatable, that's what you are . . .

By MICHAEL CAINES

After the translation prizes, the angels of translation and IKEA’s “fluency” in thirty-one languages, it may be almost a relief to find that there are plenty of words people claim to be untranslatable. Untranslatable in a like-for-like, one-word-for-another way, that is; it seems that the idea behind the word can usually be explained with easy, Johnsonian concision.

For example – have a guess at the meanings of these words, their definitions, and which languages they belong to:

Cwtch (the third one on this list)

Komorebi (fourth paragraph . . .)

Qualanquismo (the fourth one down)

Zhaghzhagh (the eighth one down)

If you scored five out of five, and as you’re reading this in English, congratulations – you’re more multilingual than Mario Vargas Llosa. And you have a very interesting and varied family background.

A complement to the helpful online collections for untranslatability from which these words are gathered comes courtesy of sometime TLS contributor Ollie Brock, who is currently a translator in residence at the Free Word Centre (on Farringdon Road, around the corner from the old TLS HQ). An edited version of the first event in a series on a theme of translation, Migration Stories, which I attended, is now available as a podcast. (See the embed above. Press play. Hear the poet Maria Jastrzebska revel in the excitement of the untranslatable! Marvel at the idea of growing up in Ghana, which speaks, “unofficially”, sixty-seven languages! Gasp as Sofia Buchuk permits us to glimpse the Quechuan spiritual world of her grandmother! etc.)

It was a good discussion, although it’s interesting to hear at the end of all this that Ollie Brock himself “doesn’t really believe in the idea of untranslatability”, despite some of his guests’ apparent delight at the irreconcilable differences between languages; that sounds like it might be the necessary attitude for a professional translator.

March 5, 2013

Mario Vargas Llosa, IKEA and Romanian

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“The TLS is the most serious, authoritative, witty, diverse and stimulating cultural publication in all the five languages I speak”

Thus is Mario Vargas Llosa quoted in an ad that appears regularly in the TLS. While it’s fantastic for the paper to have received such an encomium from the great Peruvian novelist, and his judgement is, I’m sure, entirely correct, part of it has always struck me: “. . . in all the five languages I speak”.

Even if that meant “all the five languages I am able to read proficiently”, it would still be pretty impressive. In Mario Vargas Llosa's case, that would be Spanish, English, French and . . . maybe Italian or German and Portuguese.

I thought of this quote recently, as I was happily assembling a couple of lamps from IKEA.

Along with the usual wordless images in the accompanying leaflet was a set of instructions in thirty-one — thirty-one! — languages about what to do if the item was faulty, kicking off with English (inevitably), via Swedish (a modest ninth in the running order), Slovak, Croatian, Serbian, Ukrainian, Kazakh and ending with Hindi.

It prompted me to compare the different language versions of the two-sentence instruction, which begins “If the external flexible cable or cord of this luminaire is damaged . . .". The Russian and German come out the longest — German with a mere two compound nouns — and Arabic and (Mandarin?) Chinese the shortest. The Finnish looks like a sequence of titles of tone poems by Sibelius: “taipuisa kaapeli”, “valtuutettu”, “tavarataloon”. Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Slovenian and Turkish appear to have the most diacritic marks — although Ukrainian is quite heavy on them too.

Interesting to see that the Malaysian, a language I'm totally ignorant of; appears to have several borrowings from western European languages: "kord", "fleksibel","eksklusif", "individu".

But what struck me particularly was the flowing cadences of the Romanian: “Dacӑ cablul electric al acestui corp de iluminat este deteriorat, va fi înlocuit numai de cӑtre producӑtor sau de agentul de servicii al acestuia . . .”, with its Latin inflections — “inlocuit”.

Recently, there have been some unpleasant headlines in the British tabloid press about the anticipated “invasion” next year by Bulgarians and Romanians free to travel across the EU to find work. Apart from the arrogant assumption that they would naturally want to come to Britain rather than, say, Italy, or even stay put, would it not give us the chance to learn a few words of what is clearly a beautiful language — to which most of us have up until now only been exposed through the hideous rantings of a tyrant addressing his scornful people from the balcony of his presidential palace? The current Romanian prime minister, in a counter-ploy to the tabloid headlines, urged Britons to come and visit his country. I have every intention of answering his call. I may even try to learn a few words of the language.

March 1, 2013

Cover versions redux

by TOBY LICHTIG

Early last year, my colleague David Horspool noticed a tedious trend

in contemporary book publishing: the hegemony of identikit cover designs, based

around three key themes: legs; the backs of women looking out over water; and

tiny men walking into the distance.

This discovery was, Horspool admitted, based on "five minutes of

not very systematic searching" through the TLS review copies – which just went to show how pervasive the

dreary hegemony was.

One year on, having carried out an equally unsystematic search through the current crop of review copies, I'm pleased to report

that jacket designs have come on leaps and bounds in terms of both range and

creativity.

There are currently barely any legs at all (Robert Ludlum’s The Janson Command is a notable exception), although arms are having something of a moment,

whether appearing singly, to denote yogic calm (before a fall), in the

aptly named The Sound of One Hand Killing by Teresa Solana, or multifariously,

to denote togetherness (in the face of conflict), in This Is Where I Am by

Karen Campbell.

Tiny men now carry out a range of activities – in T. D. Griggs’s Distant

Thunder, for example, one rides a horse – while the man walking into the distance in Alan Furst's Mission to Paris is medium-sized at least, and the hardback version features a couple (admittedly tiny).

Water and backs still predominate. The House on the Cliff

by Charlotte Williams is a classic of the genre, but I was glad to see this niche

broadened by a depiction of a maritime-pondering admiral, in The Poisoned Island by

Lloyd Shepherd, a coast-staring child, in Charlotte Link’s The Other Child, and a

river-gazing couple, in Scott Hutchins’s A Working Theory of Love.

Women with their backs to us can also now be found staring out of

windows (such as in Over the Rainbow by Paul Pickering; or How To Be a Good Wife by Emma

Chapman); while the backs of black-jacketed men has become a sub-genre of its own (see Gideon’s Corpse by Preston & Child; The Circus by James Craig; The Jackal’s Share by Chris Morgan Jones).

In response to David's original blog, Marika Cobbold wrote in to suggest

that it was book buyers who might be to blame for the tyranny of uniformity; book designer Jim Tierney criticized

editors, publishers and sales teams, commenting, alarmingly, that his designs

were routinely dismissed by editors for being "too literary"; and Mark Etherton

pointed readers in the direction of a pleasingly bilious blog devoted to bad

book covers, Caustic Cover Critic.

The internet being the internet, there is, of course, an entire

subculture dedicated to the subject of terrible book covers. Regularly updated

celebrations of this curiously exercising phenomenon include: Lousy Book Covers

(my current favourite is the Mad Men-esque Palm Trees in

the Pyrenees by Elly Grant – see February 21; although the girl being syringed in the head in A. Peter Perdian's Reality Reset is also quite something – see March 1st); More Bad

Book Covers (many of which appear to have been designed by a child); and Judge

a Book (compiled by a proofreader and former librarian with an eye for

"the truly hideous"); while So Bad So Good has put together a handy

list of the "top ten worst book covers in the history of literature"

(with some rather dubious titles to boot) – although it does seem harsh to put

the grinning geeks of Lorraine Peterson's admirably entitled Anybody Can Be Cool But

Awesome Takes Practice in lowly tenth position.

And these are just the covers that have been dreamed up by professionals. The Huffington Post recently reported on the slew of dreadful

book covers from the world of self-publishing.

As the recent Bell Jar controversy revealed, the subject

of cover design can become a rather febrile issue. But get it right – as Mary Beard

commented in her blog last week – and it can be a rewarding experience.

A few minutes spent perusing Lousy Book Covers and the like may send

readers gasping for the anodine security of tiny men and contemplative backs – not to mention the “too literary” faithfulness of an Esther Greenwood avatar applying her lipstick in front of the mirror.

Readers of this blog are warmly encouraged to direct us to their own

favourite trends and travesties.

February 28, 2013

Katharine, Catharine, Katherine and Katheryn

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

The other day the Editor stopped me on the way out of his office.”We’ve spelt Katherine Mansfield right, haven’t we. Why are there so many different spellings? You’re the authority . . . . Can we have a blog post?”

I certainly should be the authority by now, especially since my first name, though given a boost by the Cambridge college and Catharine Macaulay, remains one of the rarer variants, and therefore problematic. It was spelt wrongly on my bank card for years, just as it is wrong on my current work pass. When I give my email address out over the phone, I have to decelerate early on and lend the middle vowel a stern gravitas. The first time I met another Catharine, at a New Year’s Day party about four years ago, we gasped, and then hugged. I wonder how life is for the Katherines and the Katharines, the Kathryns and the Cathryns, the Katheryns and the Catheryns and the Cathrins and the Kathrins . . . .

And yes, where did we all come from? The Oxford Dictionary of First Names (2006) lists “Katherine” as the primary English form of the name of the saint martyred at Alexandria in 307 at the hands of the Emperor Maxentius. (The online OED prefers “Catherine”, as does the Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors, 2005.) According to legend, Katherine of Alexandria, a well-educated woman of noble birth (and a virgin), had converted fifty pagan savants, as well as the empress and Maxentius’s chief of staff, to Christianity. Her punishment was to be tortured on a wheel; this miraculously fell apart, at which point she was beheaded. Her cult spread from Egypt and became vastly popular, though whether she actually existed as a historical figure, no one can say. (In The Cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe, 2007, Christine Walsh writes that the cult “probably originated in oral traditions from the fourth-century Diocletianic Persecutions of Christians in Alexandria”; and that St Katherine "may well have been a composite drawn from memories of women persecuted for their faith. Many aspects of her Passio . . . conform to well-known hagiographical topoi”).

According to the ODFN, the earliest mentions of Katherine of Alexandria are in Greek, in the form Αικατερίνη (Aikaterine). The name is of unknown etymology – the theory that it may be derived from Hecate, the pagan goddess of magic and enchantment, is deemed to be unconvincing – but an association with the adjective καθαρός (katharos), “pure”, led to spellings with -th- and to a change in the middle vowel. It seems likely that a variant starting with C emerged thanks to Latin’s aversion to the letter K; and that the various forms cross-pollinated. The ODFN says that “Katheryn” was informed by the use of the suffix -yn in other names. Personal fancy has surely played a role too. Perhaps the linguists among you can tell me more . . . .

Incidentally, my mother doesn’t know why I’m Catharine with an a, but my sister grandly tells me that my father was “probably thinking of the Cathars”.

Top: Katharine Hepburn, 1940s

Below: Saint Katherine of Alexandria, c.1507, by Raphael;

Catherine the Great by Dmitry Levitsky;

Katherine Mansfield, 1912

February 27, 2013

Where is the ‘now’?

(Pussy Riot performing in Moscow before the arrest of certain members.)

By THEA LENARDUZZI

“Where are we now?” is a

phrase that has been on many lips, and on virtually every radio station, since

David Bowie released a song of that title earlier this year.

But last night the question was posed by Grey Gowrie, a man whose credentials – he is a self-declared

neo-classicist, “neither Romantic nor progressive”, and former Culture

Minister under Margaret Thatcher – suggest little in common with Bowie apart

from the near-rhyme of their surnames – and even this depends on your

(mis)pronunciation of the song writer's name (for the record, it rhymes with

“doughy”, as said of a bad pizza base, not TOWIE, the acronymic title of the

reality television show The Only Way is

Essex).

Last night – in neither

Berlin nor Brentwood, but Mayfair – Gowrie delivered the first in a series

of four lectures on the theme “The Promise of Freedom”, part of a salon hosted

by the Legatum think tank to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the coronation of

Queen Elizabeth II. Gowrie set out to consider the relationship between British

and American culture, from 1953 to the

present, with a particular focus on poetry. He is to be followed by Sandy

Nairne on Portraiture, Sir John Taverner on Music and, finally, on May 23, Dame

Harriet Walter on Theatre.

Having reiterated the

rights to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” prerequisite to

all discussion on the role of the arts in a free and prosperous society, Gowrie – whose own poems

have appeared in the TLS – discussed how poetry has, in its way, promoted the ideal of “freedom in service” that

is a central tenet of the Queen’s reign. To illustrate his belief in the power

of poets to “move a lot of weight”, he provided us each with a booklet –

its own weight and design similar to that of an Order of Service – from which

he read some of his “favourite” poems and bits of verse. We heard work from

both sides of the Atlantic, from W. H. Auden’s “The Fall of Rome” (in which

“Agents of the Fisc pursue / Absconding tax-defaulters through / The sewers of

provincial towns”) and Alan Dugan; to Robert Frost (“Earth’s the right place

for love. / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better”) and Wallace Stevens

(whom Gowrie described as having a voice that, were it ascribed a price, would

be “very expensive indeed”).

Few of us in the room

needed to be converted to the belief that “collectively poets can be quite

predictive”, that they can “advise and warn”, and each riff on the theme was

well-chosen and appreciated – I think, particularly, of one from Carlos

Williams’s “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower”, which goes: “It is difficult / to

get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what

is found there.” “I would happily do

this all night”, Gowrie admitted.

But where does the “now” of the lecture’s title

come into it? A pertinent question came from an audience member who wondered

whether poets were “now” socially, and intellectually, more marginal and

whether, if this was the case, it was because of the prosperity that had made

poetry (more) possible – in short had prosperity killed the poet?

Indeed, it is odd that

while discussing prosperity – social, cultural, financial – the internet should have gone unmentioned. Following on from Gowrie’s claim that “people who are free to

shop, are free to think”, uncensored access to the internet has increased the

political role played by the arts in bringing it to the attention of a global

audience – internet shoppers, if you will. We are now aware of the political context motivating artists in all corners of the world – Ai Wei Wei in China, for example, and the Russian

punk-rock group (I stop short of calling them poets) Pussy Riot – in a way that we could not have been before. They are, to quote a

line by R. S. Thomas, read out by Gowrie, “at the switchboard / of the

exchanges of the people.”

Referring to the “pained

conservatism” of Auden and Eliot’s remorseful poetry, Gowrie reprised the dictum

that “when the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake”. Yet, last night's discussion suggests that

though all may not be as prosperous as we'd like – again, socially, culturally, financially –the walls of the British and American establishments aren't exactly trembling with the cries of new voices.

“Where are we now?” takes on a far more narrow, British

significance, for as Hywel Williams, chairing the salon, pointed out in his

introduction: in 1953 “there was a Conservative government in place and Britain

was bust”; James Bond was big news, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot was proving surprisingly popular with

theatre-goers, and Britten was making waves with his Gloriana, which premiered as part of the coronation celebrations. Sixty

years on, Bond is big news, Beckett is in the theatres, and we are celebrating the centenary of Britten’s birth with a roster of new

books (to be reviewed in the TLS soon…) and performances of his back catalogue.

Gowrie’s question should, perhaps, be understood rhetorically, or, if

limited to Britain, easily answered with “exactly where we were” and with, in

Gowrie’s words, “nothing new at all” to say: the Greats are still great. But

what if we rephrase the question slightly? “Where is the ‘now’?”

The joy of parody?

By MICHAEL CAINES

You can’t always say that preparing to speak in public – or in

my case, this week, to chair a public event – is an opportunity for joy. But

when the subject is “The Art of Parodies” (tickets available here), the title for a panel discussion this Friday night at the LSE, as part of their fifth Space for Thought Literary Festival, preparation

can be nothing but a pleasure.

For example, it involves:

Re-reading Craig Brown’s “extract” from the diary of David Hare

(“The State of Britain, Part One: Three

days ago, I went to a party. I don’t often go to parties, because I’m not that

kind of person, I’m a playwright, with more serious concerns. But I went to

this one. By bus, of course. I’m not the sort of person who takes taxis. So I

hailed a double-decker in the King’s Road and told the driver to take me to

Islington. He was then to wait for me outside the party for an hour or two and

take me back. The instructions were quite clear. But of course this is Thatcher’s

Britain . . . .”)

Re-reading Jane Austen’s parodies of sentimental novels, etc

(“The perfect form, the beautifull face, and elegant manners of Lucy so won on

the affections of Alice that when they parted, which was not till after Supper,

she assured her that except her Father, Brother, Uncles, Aunts, Cousins and

other relations, Lady Williams, Charles Adams and a few dozen more of

particular freinds, she loved her better than almost any other person in the

world.”)

Revisiting Ewan Morrison’s much-discussed piece about fan

fiction from last summer (he’s one of the speakers, alongside D. J. Taylor and

Martin Rowson; the piece only mentions parodies once, but it raises the relevant questions

about imitation and “fans becoming creators”)

Reading as much as possible of a borrowed copy of the Oxford

Book of Parodies, edited by a former TLS editor, the late John Gross. The first sentence of Gross’s introduction hands you a straightforward

definition: “A parody is an imitation which exaggerates the characteristics of

a work or a style for comic effect”. But is comedy the real point of the exercise?

Is the target the book or author being parodied, or something or somebody else? There

are, Gross points out, parodies that mock, and parodies that are “affectionate”

(although presumably a parody could be both of those things, and the real

opposition lies between affection and hostility, between friendly ribbing and the

unfriendly desire to maim your opponent); there are “exquisitely accurate”

imitations of another writer’s style and those that are “rough-edged but effective”.

Is there any point in striving for “exact definitions” of such a protean genre?

One last piece of reading: there are examples of some extremely

effective mockery of some of our most widely praised and popular contemporary

authors in one of the inspirations for the LSE event, the fine collection of

Private Eye take-offs recently published as What You Didn’t Miss: A book

of literary parodies, compiled by D. J. Taylor (who also turns out to

bat for the TLS on occasion).

The victims include Zadie Smith (“One may as well begin with

Kiki in the delicatessen”), Philip Hensher (“It was 1974 in Sheffield and the

Fothergills were having a party. The guests ate Coronation Chicken, hula hoops,

Black Forest Gateau, potatoes wrapped in foil with cocktail sticks spiked with

cheese and pineapple . . .”) and Andrew Motion (the author here of “How Boileth

Ye Pot”, a “new civic ‘liturgy’ of the theme of St George”). There’s Graham

Swift on being good at “noticing things”. “It’s my job . . . Noticing things. I’m

a writer. Take water, for instance. It’s just melted ice.” (To which his agent

replies: “That’s good . . . I like that . . .”.) One hopes that all of them can

take a joke. There really isn’t any writer or any style of writing that can’t

be made to seem ridiculous.

And I’m looking forward to being contradicted on all the

points above on Friday night at the LSE . . . .

February 26, 2013

Jewish life in modern Germany

By TOBY LICHTIG

In the aftermath of the Second World War, there were

some 250,000 Jews living in Germany, the vast majority "displaced

persons", housed in temporary camps. After the state of Israel was founded

in 1948, most emigrated, and the population quickly dwindled to one tenth of that amount.

But the small German Jewish community very gradually

grew, bolstered in the 1950s and '60s by a trickle of returnees and, following

the collapse of European Communism, an influx from the former Soviet Union.

Today, there are over 110,000 Jewish Germans, an estimate that more than doubles

if non-practising immigrants of Jewish origin – or with only Jewish fathers –

is taken into account. There is also a significant number of Israelis living in

the country – 18,000 in Berlin alone, according to a recent report. For many years now, Germany has had the fastest growing Jewish population in Europe.

The state of contemporary German Jewry was the subject that kicked off Jewish Book Week on Saturday night, in the form of a stimulating,

if sometimes circumlocutory, conversation between Olga Grjasnowa, a German

writer born in Azerbaijan, and Dr Rafael Seligmann, a history teacher, author

and founding editor of the Anglophone German newspaper Jewish Voice from Germany. Chairing the debate, entitled

"Dilemmas of Difference", was the filmmaker and broadcaster Tina

Mendelsohn.

Seligmann, whose German parents moved to Israel after

the war and returned to Germany in the 1950s when he was a boy, was pragmatic

about the reasons for the ex-Soviet influx, concluding that, "for 90 per

cent of them, it's to do with economics", rather than

ethnicity or spirituality – a statement that wasn't in any way designed to

downplay the importance of this community to Jewish cultural life. Seligmann

took an equally unflustered approach to the eternal question of Jewish

identity: "If he or she says 'I'm a Jew', they’re a Jew!"

A wry and playful debater, who celebrated the fact

that Germany now boasts a thriving society of "Jewish writers and Jewish

doctors and Jewish criminals", Seligmann argued that only in recent years

have German Jews begun to feel "German" once again. He also stuck up

for the new immigrants who, he claimed, continue to be marginalized within Germany,

as evidenced by their woeful underrepresentation on the German Jewish Central

Council (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland).

Less convincing was Seligmann's contention that

"only in Israel" do Soviet Jews escape stigmatization as "not

proper Jews" – a prejudice born from the decades of suppression of Jewish

cultural life and religious practice under Soviet rule, and promulgated in Israel as much as anywhere else. Even if times are now changing, the Israeli assimilation story has been a fraught one.

Grjasnowa vigorously disagreed with

Seligmann on this point, drawing on her experience of living in Israel, during

which time she frequently felt pressured by the authorities to

"prove" her Jewish legitimacy. As so

often in contemporary debates about Jewish identity, Israel threatened to

monopolize the conversation, and, on at least one occasion, Mendelsohn was

forced to plead: "But let's talk about Germany!"

Anti-Semitism then became the focus of

debate, with Seligmann drawing upon two recent furores to underline the prejudice

that, both panellists felt, still bubbles below the surface in Germany. (Both were quick to underline their belief that this is no more or

less endemic to their country than any other European state.)

The first controversy was Günter Grass's 2012 poem "What Must Be

Said", which drew parallels between Iran's nuclear ambitions and Israel's

nuclear open secret – although neither commentator had much to say about the

subject, nor about the endlessly fraught question of where opposition to

Zionism (in its Likud-dominated, expansionist sense) ends and anti-Semitism

begins.

The second controversy was the recent (and swiftly

overturned) decision by a court in Cologne to ban circumcision, having equated

it with criminal bodily harm. Seligmann rightly drew attention to the platform

this debate provided for an outpouring of ill-informed xenophobia, a

"nasty discussion about foreigners and foreign practices" (the whole

thing was, he said, "an alibi for old prejudice"). What no-one on the

panel mentioned was that this court decision was made in the light of a

tragically botched circumcision on a young Muslim boy. There is a healthy

debate to be had about the rights and wrongs of circumcision, and it doesn't need to bring in either anti-Semitism or Islamophobia.

Sights then turned on the Holocaust. Mendelsohn claimed

that, "for Germans, the Shoah was a long time ago, for Jews it is

not"; and Seligmann pointed out the difficulties faced by the non-Jewish German post-Holocaust generation, arguing, provocatively, that "it is harder to

be the child of Cain than the child of Abel".

Where the evening, I thought, came up short was in its

appraisal of the positive stories about contemporary Jewish German life: the

very fact that there is now a newspaper called Jewish Voice from Germany. There was brief mention of a

"German-Jewish Renaissance", but little indication of what this might

comprise, and a dragging sense (from this small sample at least) that Germany's

horrific past remains inescapable.

My own late grandparents, who were Berlin refugees,

would have been interested to witness this debate, their conflicting personal

outlooks highlighting the ambivalent attitudes harboured towards Germany by

Jewish refugees of their generation. Following his escape in 1938, my

grandfather expressed no desire to return to Germany and affected an American

accent in a (futile) attempt to hide his Berlin drawl. My grandmother, who lived to see

the new millennium, felt German to the core, and, in the years after her

husband's death, made regular visits to her homeland with several of her German

emigrant friends.

There is a fine line between commemorating,

remembering, never forgetting and

being hamstrung by the weight of history. A quick browse of Jewish Voice from Germany gives an

indication of where we may be today. The newspaper, which is wide-ranging and

well-written, features stories on an array of contemporary issues – the

"flourishing" Jewish community, the circumcision debate, current

anti-Semitism, Israeli science, Turkish politics, Azerbaijani gas reserves,

Berlin fashion – and a slew of articles beginning with sentences such as, "Some eighty years ago"; "Before 1933"; "The

persecution and annihilation of German Jewry"; and, simply, "Auschwitz.".

It may be argued that the real sign of healing comes when the

impulse to look forwards outweighs the need to look back. We appear to be at

least part of the way there. Perhaps in another generation the balance will be tipped.

A Brit in the Académie

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The poet, literary critic and professor at the Collège de France, Michael Edwards, has just become the first Briton ever to be elected to the Académie française. The appointment is for life.

Edwards taught at the University of Warwick and has been at the Collège de France since 2002. In a paragraph announcing the news (February 23), Le Monde pointed out that “in his articles for the Times Literary Supplement, [Professor Edwards] has always striven to create links between French and English poetry” - which is kind of them as he hasn’t written for the TLS for some time.

Founded in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, the Académie has as its principal role that of guardian of the French language. It also produces a dictionary (the 9th edition is in preparation) and hands out important literary prizes, including the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie française.

Edwards, who was born in 1938, joins the 40 “Immortels” and will occupy Fauteuil 31 (there is as yet no photo of him on the Académie’s website). He will be expected to wear the traditional green uniform and carry a sword. He will also have to deliver a eulogy to the previous occupant of his Fauteuil. If memory serves, the late Alain Robbe-Grillet refused to fulfil this duty when he was elected in 2004. Henry de Montherlant, meanwhile, asked to give his eulogy in 1963 behind closed doors.

Edwards’s successful application was at the third time of asking. He comfortably defeated his 5 rivals after 3 rounds. Rather unkindly the Académie publishes a full breakdown of the voting.

For what it’s worth, Émile Zola applied 24 times, without success. The list of non-members among writers is a distinguished one, including Molière, Diderot, Stendhal, Flaubert and Proust - none of whom presumably ever applied.

There have been 7 women among its 722 members. Marguerite Yourcenar was the first in 1980. Current Immortelles (if there is such a term in this context) include the politician Simone Veil and the Algerian novelist Assia Djebar. The former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing is also immortel. The election of the poet and first President of Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor in 1983 is regarded as having broken a very conservative mould. It'll be interesting to see if Edwards is joined by another "Anglo-Saxon".

February 24, 2013

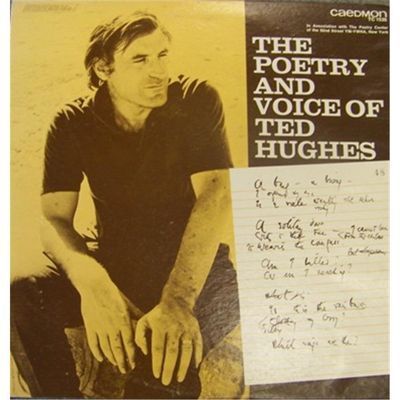

Literary vinyl

This week, a new kind

of collector came across the radar of the TLS: the collector of “literary vinyl”. An

astonishing archive is up for grabs. And it could be yours. As J.C. reports, even at $80,000, it’s still a snip:

We know simple-minded book collectors, in love with early orange Penguins; we

know High Fidelity-type maniacs, for whom the whisper of “vinyl” is an erotic

invitation. Until now, though, we had never encountered a collector of

“literary vinyl” – spoken word LPs, singles, and those oddly appealing 10-inch

discs. Greg Gatenby reckons he is the world’s leading collector of literary

records; he has 1,700 of them, and is now offering to sell the collection as a

single lot for $80,000, roughly $50 per disc.

Mr Gatenby is the former director of the Harbourfront literary festival in

Toronto, and the organizer of weekly readings. During his tenure, he

tape-recorded “every onstage utterance for posterity”, at the same time

stacking up the vinyl. Here is one small part of the catalogue, relating to

discs by Albert Camus:

Albert Camus lit L’Étranger.

Albert Camus Reading in French: La Peste, La Chute, L’Eté, L’Étranger.

Albert Camus Vous Parle (10-inch record).

Albert Camus: Le Mythe de Sisyphe lu par l’auteur.

Albert Camus: His works and his voice.Présence d’Albert Camus: Textes et commentaires dits par l’auteur. (Features a

portrait of Camus by Maurice Tapiero specially commissioned for this boxed set.

Camus reads excerpts from Noces, L’Homme Revolté, Caligula, La Chute, etc. The

discs also feature excerpts from press conferences and interviews.)

To continue

only with the French, there are recordings by Apollinaire (two items, one with

cover art by Picasso), Cocteau (twelve items), Colette (eight), Duras, Gide,

Giono, Giraudoux, Malraux, Mauriac. Imagine a 7-inch recording of Alain Robbe-Grillet,

with William Burroughs on the flipside. Mr Gatenby has it. On one record, Maya

Angelou sings (Miss Calypso), on another reads poetry (sleeve note by James

Baldwin). Did you know that Baldwin and Margaret Mead recorded A Rap on Race in

1972? Of course you didn’t; only Mr Gatenby does.

The list alone is good for an

hour’s browsing: Truman Capote reads In Cold Blood; Saul Bellow reads Herzog;

Ted Hughes (pictured), Julio Cortázar, William Faulkner. When he began

collecting, Mr Gatenby tells us, “literary LPs were being thrown in the garbage

by librarians”. Guarding the voices was part of his “record-keeping”. It is a

mystery to us why he’s willing to part with it. What can you do with $80,000

nowadays? Bids are solicited on eBay. The seller will send a complete list to

interested browsers.

J. C.

February 22, 2013

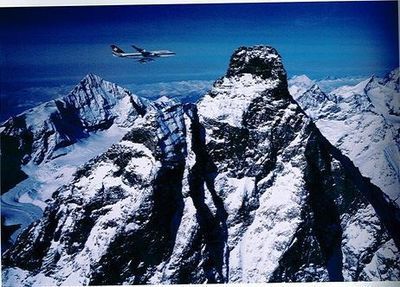

Swissair for ever

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Every now and again a book comes into the offices of the TLS that makes this job worth while. Swissair Souvenirs is just such a book. Published by the ETH-Bibliothek in Zurich, it’s a compilation of images, taken from its archives, that chronicle the airline that, surprisingly and “to the dismay of the Swiss people”, went bankrupt in 2001. It’s suggested that Switzerland’s non-membership of the European Union may have been a contributing factor to its demise.

Among the things I learn from this book is that the airline became known as the “flying bank” and that in 1970 it flew to 75 cities. Its reach was hugely disproportionate to the country’s size.

When I was a child we moved around a lot as a family, by ship or plane. I became familiar with several airlines, such as the precursor to British Airways, BOAC (commonly known as Better On A Camel), the Portuguese carrier TAP (Take Another Plane), TWA (Try Walking Across), or the Belgian national carrier Sabena (Such A Bad Experience, Never Again). Not absolute thigh-slappers perhaps, but the tags stuck.

Swissair’s name resisted such ribbing, and it was always my favourite airline; maybe it had the best chocolate, or perhaps it was the most punctual. It certainly had a pretty logo, and flying over the Alps (below) was an added attraction.

Some early flights look like they were best avoided (below). Such photos are passed off without comment, but it's surely to the airline's credit that they are shown.

Along with technical specifications - there are photos of aircraft workshops and the like - most aspects of the airline’s activities were photographed, from food preparation . . .

to on-board catering:

Plane-spotting was clearly a popular national pastime too (below). Happy days.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers