Peter Stothard's Blog, page 69

November 16, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 7

By J. C.

Our favourite second-hand bookshop in London is among the most central: Any Amount of Books in Charing Cross Road. Fifty yards north is Quinto; a few steps south is bibliophiles’ alley, Cecil Court. At Any Amount, they pile them high and sell them cheap. The staff are kind to the passing customer looking for “a book by someone whose name I can’t remember”, and generous with discounts. Outside, barrows offer books at £1 each – the very barrows in which we found The Face of England by Edmund Blunden, which began the Perambulatory series.

On Sunday, we walked along Whitehall in the wake of the Remembrance ceremonies, crossed Trafalgar Square and entered the bookshop. The Perambulatory Constitution, available for inspection in the basement labyrinth, states: “We seek a neglected book by an established author. We do not seek collectibles. All books are bought to be read”. With relief, among the amendments in tiny print, we read: “Exceptions may be made”.

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner is not neglected. We have read it more than once. But in Any Amount we laid hands on an edition which, though perhaps not collectible, is none the less a curiosity and deserves not to be passed over. The novel was written in six weeks, while Faulkner worked at a power plant. The publisher in 1930 was Harrison Smith and Jonathan Cape. A “second state” was issued in the same year, and, in 1935, a second edition, by Smith and his new partner, Robert Haas. The copy before us is neither of those: it is a second printing, dated 1933. The curiosity value resides in the fact that the publisher is Smith and Haas, whereas the only Smith and Haas edition we can find reference to is the 1935 one. A Faulknerian friend of ours, an expert on As I Lay Dying, has never seen a copy of the edition now in our hands.

It is a beautiful book, no dust jacket, with the title and author’s name imprinted in oxblood on khaki cloth. A drop of wine has been spilled on page 153; otherwise, it is in splendid condition. The first printing tends to go for hundreds, if not thousands. We will read it again, muttering, “Eat your e-book heart out!” Any Amount charged us £6.

Perambulatory correction: The Unknown Sea by François Mauriac, discussed last week, was published in French in 1939 (Les Chemins de la mer), not 1947 as stated.

November 14, 2012

The Bibliomania and its cures

By MICHAEL CAINES

Regular readers of J. C.'s perambulations will know by now that the aim is to buy second-hand "books to be read", rather than books to be treasured, locked in a bank vault, insured for millions, or donated to the nation in lieu of tax. (And for most of us: chance would be a fine thing.)

If you're not so much a reader as a collector, however, a bibliomaniac rather than a bookworm, you have learnt to treasure books not so much for their insides as their outsides; and according to Thomas Dibdin, you have a problem. The TLS cynically feeds your addiction by running occasional pieces on astounding sales at Sotheby's or the vexed history of private collections. But new regulations mean that I'm now bound to offer you at least the standard guidelines for kicking the habit, courtesy of the Revd Dibdin, who inspired the establishment of the Roxburghe Club in 1812.

A few years before that, in 1809, in The Bibliomania; or Book-Madness, Containing Some Account of the History, Symptoms, and Cure of This Fatal Disease in an Epistle to Richard Heber, Esq., Dibdin outlined the history (mainly a chronicle of notable British sufferers from the fourteenth century onwards), symptoms and solution to your problem.

The symptoms? A passion for first editions and illustrated editions, books with uncut pages, rare or unique copies, books printed on vellum or in blackletter. (To this list, which is Dibdin's, you might now add the dangerous lust for association copies.)

The consequences? Potentially severe. There was the humanist scholar Roger Ascham, "notorious for the Book-disease", who Dibdin suspects died "in the vigour of life", "in consequence of the BIBLIOMANIA", and was followed by many another man of letters (Dibdin believes women to be immune to the disease). There are the ruinously high prices paid at auctions ("the hammer vibrates, after a bidding of Forty pounds, where formerly it used regularly to fall at Four!"). There is the threat, Dibdin argues, that an epidemic of book-collecting poses to the health of the nation. And Heber himself – Dibdin's dedicatee and the eventual owner of some 100,000 volumes – wrote a poem on the same theme in which he offers a vision of the bibliomaniac confronted by a classic work in which the margin is not wide enough:

In vain might HOMER roll the tide of song,

Or HORACE smile, or TULLY charm the throng . . .

The Bibliomane exclaims, with haggard eye,

"No Margin!" turns in haste, and scorns to buy.

But what's the cure? Dibdin prescribes, among other things, a course of "useful" reading for the individual, compelling them to look beyond the binding and the title-page. He recommended the editing and reprinting of old books, and the "powerful antidote" provided by public libraries (but not circulating libraries, those "vehicles . . . of insuferable [sic] nonsense, and irremediable mischief!").

Forcing myself to consider parting company with a few volumes – with an office move only a couple of weeks away – I found myself wondering if Dibdin's cure could make the process any less painful. Libraries, reading lists and new editions exist and are available to me. The shelves refuse to empty.

Further advice, however, comes from another source, that will be familiar to readers of Harold Love's Penguin Book of Restoration Verse. William Wycherley, best known for his comedy The Country Wife, suggests that all you need to do is think again about the books in your life, and why they're in it:

"Advice to a Young Friend on the Choice of his Library"

Thy Books shou'd, like thy Friends, not many be,

Yet such wherein Men may thy Judgment see.

In Numbers ev'n of Counsellors, the Wise

Maintain, that dangerous Distraction lies.

Then aim not at a Croud, but still confine

Thy Choice to such as do the Croud out-shine.

Such as thy vacant Hours may entertain,

And be thy Pastime, not thy Life constrain;

Not dark, mysterious, crabbed, or morose,

Useless, and void, or stupidly Verbose,

Tho' witty, yet judicious and sincere,

And like true Friends, still faithful, tho' severe;

Books that may prove, in ev'ry Change of Stage,

Guides and Assistants to your shifting Fate:

That may to Virtue form your early Soul,

And the first Thought of unripe Guilt controul.

Friends, whose sage Wit, call'd up at each Extream,

May help you to converse on ev'ry Theme;

And when retir'd from Business, and alone,

Delight you with their Talk, and spare your own.

Make short the Season of the restless Night,

And force dull Hours to mend their ling'ring Flight.

Then, wheresoe'er your wand'ring Steps you guide,

May travel with you, and close up your Side:

Relieve you from the Pageantry of Courts,

Their gawdy Fopp'ries, and their irksome Sports:

Or, if some dire Necessity require,

With you to Dungeons for your Aid retire.

And still, like Friends, your Sadness to prevent

In Prison, Want, Distress, or Banishment.

Like Friends, it matters not how great, but good;

Not how long known, but how well understood:

Imports not, though without they old appear,

If new and just the Thoughts within 'em are:

So that, like old Friends, still they ready be,

Open at Will, and of Instruction free;

Whose faithful Counsel soars above the Art

Of servil Flatt'ry, to seduce the Heart:

But its instructive, honest Dictates lends,

Void of Design, or mercenary Ends.

Unlike most other Friends, less tiresome too,

As with them still you more acquainted grow.

As in Dibdin's Bibliomania, Wycherley's poem seems to have more than book-collecting on its mind. But is it enough to undo years of hoarding books that are "great" rather than "good"?

November 9, 2012

Goncourt 2012

by Adrian Tahourdin

This year’s Prix Goncourt has gone to Le Sermon sur la chute de Rome by Jérôme Ferrari. The book is published by Actes Sud.

The prize is worth 10 euros, but Ferrari can be guaranteed a huge increase in sales.

This is the second time the Arles-based publishing house has delivered a Goncourt winner: in 2004 Laurent Gaudé’s thoroughly mediocre Le Soleil des Scorta was crowned, but it seemed more like a gesture of encouragement to an admirable non-Paris-based publisher than a true reflection of the book’s merits. The big three Parisian publishers Gallimard, Grasset and Seuil have long been known as Galligrasseuil by those who have suspected that they wield undue influence in the awarding of literary prizes.

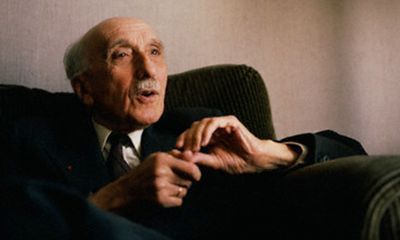

In a spirit of increased transparency one of the Goncourt judges, Pierre Assouline, has revealed that the vote went 5-4 in favour of Ferrari – Patrick Deville being the runner-up for Peste & choléra (Seuil).

The forty-four-year-old Ferrari, who teaches philosophy at the French School of Abu Dhabi ("I try to persuade people to study philosophy in French for $15,000 a year"), has also taught at lycées in Algiers and Ajaccio in Corsica – where his new novel is set.

Ferrari didn’t have to endure the near-asphyxiating media crush Michel Houellebecq suffered when he won the Goncourt in 2010. Just as well, as he had just flown in from Abu Dhabi.

Le Sermon sur la chute de Rome will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 6

By J. C.

The tidiness virus courses through London’s second-hand bookshops (see NB, last week). Even the Archive Bookstore – the original temple to chaos – has succumbed. “You can get through to modern first editions now”, Tim, the owner of the shop in Bell Street, close to Marylebone Station, told us last week. We detected a note of apology undermining his pride. “It is possible that my assistant has been weeding too diligently.”

Sherry was being dispensed in tea mugs. An impecunious customer was being offered a handsome loan, while a hopeful seller was facing a pitiful sum for his books. An elderly gentleman with a resemblance to the Major in Fawlty Towers was explaining to a young woman from Poland that his late wife had been a stripper. On certain days, browsers listen to Chopin improvisations rising from the basement, where stands a piano with wooden keys. The Polish woman was filming everything for a course in documentary at Royal Holloway. She couldn’t believe her luck. Even in its disgracefully tidy state, the Archive Bookstore is unique.

As the camera rolled, we took advantage of strangely accessible shelves. The mission is to celebrate the bountiful second-hand trade, and to find a neglected work by an established author as alternative to vile Christmas fare, for about £5. All books are bought to be read.

The notion of the “Catholic novelist” seems quaint now, but some of the most populart names in post-war British fiction were once thus classified: Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, Evelyn Waugh. Across the Channel, François Mauriac (1885–1970) was the high priest until the onset of a reformation brought about by a band of young, atheistic rebels, one of whom wrote The Rebel. Mauriac’s stature began to dwindle from the moment Sartre attacked him for denying his characters free will. Numerous works were translated into English after the award of the Nobel Prize in 1952, but Mauriac has scant presence here now. Titles such as Life of Jesus are unlikely to create a revival, though a new film of his best-known novel, Thérèse Desqueyroux, with Audrey Tatou of Amélie fame in the title role, might help when it is released in the UK and US next year.

We were ignorant of The Unknown Sea, until finding it on the orderly shelf. Published in French in 1947 (Les Chemins de la mer), it tells the story of the Revolou family in Bordeaux, Mauriac’s native region. The familiar counters of French fiction are present in the opening chapter: money and property (not the same thing), love and marriage (ditto), the faithful servant, the errant husband, the revolver in the drawer. Mauriac said he made use of “devices that came from silent films” in the writing of his novels, including a “sudden opening”, and a deliberate absence of preparation for the reader. When asked if his faith had hampered or enriched his literary life, he answered “yes, to both parts of the question”. As we left the Archive, after handing over £1.50 for The Unknown Sea in a handsome 1962 Penguin Modern Classics edition, translated by Gerard Hopkins, Tim was talking about a signed Leaves of Grass he had sold for a song. The Major was trying to find the Polish for “striptease”. The November evening seemed much cheerier.

November 6, 2012

Bram Stoker at the theatre (with Wilkie Collins)

By MICHAEL CAINES

As has been mentioned in the TLS from time to time, Bram Stoker, the man now known as the author of Dracula, would have been known in the nineteenth century as the business manager of Henry Irving's theatre, the Lyceum, in London. That makes them partners in the production of melodrama: while Irving stalked the stage, dying, guilt-stricken, in The Bells or some similar piece, night after night, Stoker handled the correspondence. Phil Baker, reviewing a biography of Stoker a while ago, mentions that he wrote around half a million letters on Irving's behalf.

Usually, once noticed, that Irving-Stoker-Dracula connection starts to take on some historical-critical-biographical significance. Was the great actor a source of inspiration for his confidant's infamous creation? Was it merely a private joke that Jonathan Harker was to attend a performance of Vanderdecken – a stage version of the Flying Dutchman legend in which Irving played the lead and which Stoker himself partly rewrote in 1878?

(That was just before Stoker took up his duties at the Lyceum; the section was later cut from the novel, noted a correspondent to the TLS in 2003).

The centenary of Stoker's death fell earlier this year – so it's good moment to be sounding the full depth of his engagement with the theatre. This is something promised by Bram Stoker and the Stage, a new compendium in two volumes, edited by Catherine Wynne.

On her account, Stoker's theatrically inspired writings include only a single piece of fiction ("Snowbound: The record of a theatrical touring party"), but there are several interesting essays here, as well as some dignified pieces of reminiscence (Stoker dedicated a whole book to Irving, from which Wynne provides extracts).

Some of these pieces make curious reading today. With Irving in mind, for example, Stoker could claim that putting actors in charge of the "most important playhouses" was "simply a process of evolution", a "process of devolution of stage power into the hands of the players". Actor-managers no longer run the whole show at the National Theatre or the Royal Shakespeare Company, so was Stoker wrong about that, or has the theatre simply evolved still further? Acting and artistic programming need not be exclusive talents, as shown in recent times by Mark Rylance at Shakespeare's Globe, Ian McDiarmid at the Almeida and Ian Talbot at the Open Air Theatre in Regent's Park. (That leaves Kevin Spacey at the Old Vic; there must be more, outside London.)

Most intriguingly, perhaps, Wynne reaches back beyond Irving to the early 1870s, when Stoker was starting out as a theatre reviewer for the Dublin Evening Mail. It is here that you may find a fascinating encounter between the future "vampiricist" and his forerunner in sensation and shock, Wilkie Collins.

In April 1872, fresh from reviewing Dion Boucicault's Rip Van Winkle ("The plot is . . . very slight . . ."), Stoker turned his attention to Collins's own adaptation of The Woman in White, which came to the Theatre Royal in Dublin after its London run. (Collins adapted several of his works for the stage, and let others attempt to adapt them, too.) The outcome was a trilogy of short pieces (the middle one being a single paragraph), largely ruminating on the question of adaptation. One might retrospectively find some irony in this, given the comparable fate of Dracula itself, adapted for every medium under the sun – which one hears is very bad for the undead.

"Mystery is tolerable in a novel", Stoker writes in the first Woman in White piece, "but fatal on the stage; and whereas in the latter it is perfectly good art to show fully the development of the plot, it is wrong to conceal any of its workings to an audience." Collins's approach strikes him as "masterly" in its flexible rearrangement of the basic materials of the novel. This leads him to go into the plot in some detail, seemingly on the assumption that his readers are so familiar with the novel that they need only this outline to recognize Collins's adaptable ingenuity. The dramatic version's single fault, he feels, is that "it has no humour", and this, too, is cause for theorizing about the difference between novels and plays:

"The tone of the novel is essentially gloomy, and Mr. W. C. doubtless wished to preserve its great characteristic; but he overlooked the fact that the action of a drama is so concentrated, the suspense so great, and the strain on the minds and feelings of the audience so intense, that occasional relief is necessary. Even Hamlet requires the gravedigger and Lear the fool."

(But this is to forget the "hilarious" opening exchange in Collins's self-adaptation between Sir Percival Glyde and Anne Catherick: "What are you doing in the churchyard?" "Thinking of the dead." "Suppose you try a change. Take a walk in the village, and think of the living." "I have no friends among the living." Etc.)

As played by George Vining, on the other hand, Count Fosco is apparently an improvement on the character in the book: "He has given us a perfect character – one who is unmistakably natural throughout all his phases. The Fosco of the novel is not natural . . .".

Coming back to the production a few evenings later, Stoker could enthuse that it was "among the most successful dramas ever produced on the Dublin stage", not least because Vining "succeeds in portraying the remorseless villain of the mysterious tale". Further high praise comes in the third piece, along with some revealing remarks on what Stoker thinks is the secret of the piece's success. Collins has done well, he says, to resist the temptation to "introduce mechanical effects and sensation tableaux": a "much better effect is produced by the legitimate means of character painting, and the gradual development of the plot". "The whole tone of the play is that of suppressed force; and this is not confined to either the play as a whole, or to its various characters, but to each all alike. The true force of tragedy consists in suppressed strength – the dread of something more appalling than that which is represented – the shadow of some danger hovering near . . . ."

Stoker's response to Collins makes curious reading in the light of the parallel sensations caused by both of these authors' most famous works, and the theatrical Woman in White seems to have meant a great deal to the younger man: at Stoker's death in 1912, the manuscript of the play (a gift from Collins?) was still in his library. Irving and Collins, meanwhile, were already well acquainted by the 1870s, making the Stoker connection seem even more apt. At least, that's how it appears to me – and if you didn't think it already (and it has been occasionally noted), you might start to suspect that Collins the dramatist had in fact been a greater influence on Stoker's imagination than Collins the novelist. Whatever the truth of that, Catherine Wynne puts it well in her introduction to Bram Stoker and the Stage*: Dracula is "deeply indebted" to the theatrical experiences of its author for its "melodramatic or stagey qualities". For a post-Halloween treat, flick through a few pages and see if you agree.

* To be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.**

** As will a rare new book about Boucicault, mentioned above in passing.

November 2, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 5

by J. C.

After a previous visit to Slightly Foxed on Gloucester Road, we remarked that the stock was “well regimented”, with the books strictly disciplined and marshalled into tidy display. This was in reference to the first law of perambulatory chaos theory: secondhand bookshops thrive on disorder. The owner of Slightly Foxed (in other respects a charming shop) responded, with little attempt to disguise the irony, that he and his staff had had “a wonderful time” making the tidy untidy.

We risked a return, incognito. Good quality hardback and paperback books are arrayed on the ground floor, reasonably priced, as well as some covetable collectibles. In the basement, the tidy tyranny endures, but a healthy wall of ancient paperbacks competes with the neat arrangements elsewhere, and it was here, naturally, that we found the sought-after curiosity to keep the Christmas giftbook blues at bay. Dead Fingers Talk by William Burroughs is indeed a curiosity. It was the book under review in the TLS of November 14, 1963, beneath the famous headline “Ugh . . .”. John Willett’s disgusted assault on the author sparked thirteen weeks of correspondence, and had the unintended consequence of launching Burroughs as an avant-gardist of renown. “If the publishers \[John Calder\] had deliberately set out to discredit the cause of literary freedom, they could hardly have done it more effectively”, Willett wrote. Among those who rose to Burroughs’s defence was Anthony Burgess, calling him “the first original since James Joyce”.

But Dead Fingers Talk is yet more curious than that. In 1963, Naked Lunch and the author’s other Paris-published books, The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded, could not be issued in Britain without risk of prosecution. Dead Fingers Talk was thus concocted as an amalgam of all three. It also contains material unique to itself, yet critics and biographers pay it scant attention. The Burroughs Reference Guide by Michael M. Goodman calls it “a rewrite of Naked Lunch [which] places the events in proper linear sequence”, a good enough reason for taking note of it.

For a 1966 Tandem paperback, previously unknown to us, Slightly Foxed charged £4. It seemed appropriate that the book fell to pieces the moment we opened it, not having been exposed to the light of day for decades, but we were no less happy with our find. The horrible junkie cover alone is worth the money.

October 28, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 4

By J. C.

While reading Artemis Cooper's biography of Patrick Leigh Fermor last weekend, we learned that in the early 1950s he interrupted work on his "Greek book" (which became Mani), to translate two novellas by Colette: Chambre d'hôtel and Julie de Carneilhan, published in one volume as Chance Acquaintances (Secker, 1952). Wouldn't it be fun to read them, we thought . . . .

to see how the unbridled Paddy pen took advantage of the well-behaved Gallic page? Without giving it another thought, we returned to Ms Cooper's affectionate biography.

The next day, we made for King Street, Hammersmith, from where word had reached us of a "not bad" shop, Books for Amnesty. The mission, you may recall, is to seek as a heartening alternative to vile Christmas giftbook fare a neglected work or curiosity by an established author, for about £5. Books for Amnesty is indeed not bad. There is a skippable fiction section, halfdecent assortments of poetry and "classics", and a large selection of LPs. A sales assistant was advising a customer that A Clockwork Orange was unavailable because "it was banned for so long", forcing us into a reluctant correction. On the classics shelves, our eye fell on four volumes from the Secker Uniform Edition of Colette. Surely it couldn't be? Chéri ... Claudine ... Gigi ... Chance Acquaintances! "Translated by Patrick Leigh Fermor." PLF complained to Diana Cooper that the job of correcting the proofs was "like some awful imposition at school". The gnarled opening sentences reflect his impatience: I did not acquire my habitual mistrust of nonentities over a period of years. Instinctively, I have always held them in contempt for clinging like limpets to any chance acquaintance more robust than themselves. It is only since I first encountered human barnacles that molluscs equipped with contractile nerve-cords have filled me with horror.

After that, the story, with Colette herself at the centre, goes smoothly. Ms Cooper says that Chance Acquaintances is not "considered among her best work", and PLF himself wrote: "I'm beginning to think she's fearful rot", but we enjoyed the charming title novella set in a mountain spa. How much of it is Colette and how much Paddy, we have not had time to ascertain but will make it the subject of a further report, unless someone enlightens us first. Books for Amnesty asked £3 for an appealing, pocket-sized hardback.

With a few pennies left in the kitty, we chose another book with a Fermor connection: Roots of Heaven by Romain Gary. The screenplay for the 1958 film by John Huston is PLF's work. When presented with the first draft, the producer Darryl Zanuck did not say, "It's fearful rot". He did say, "It's a whole heap of crap", as Paddy told Deborah Devonshire. Shooting took place in Cameroon.

The female lead was Juliette Gréco, with whom Paddy got on well: "wild, rather like a panther, with a tremendous sense of humour", he told the Duchess, adding, "I rather love Juliette Gréco". Doesn't everyone? In exchange for a solid orange Penguin (1960), Amnesty augmented its justice fund by a further £2.50. Ms Cooper's biography will be reviewed in a future issue.

October 25, 2012

Out of East Anglia

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Journalists, students, proud parents and friends gathered around bowls of crisps (those ones with beetroot) and bottles of British sparkling wine last night for the launch of the UEA Creative Writing Anthologies 2012 at the LRB Bookshop in London. A selection of graduates read roughly three minutes’ worth of their work, the Tracy Chevaliers and Kazuo Ishiguros of the future; we listened.

UEA’s association with creative writing courses goes back to 1970, when Angus Wilson and Malcolm Bradbury founded a course for prose fiction writers looking to hone their craft in an academic environment. A Poetry course was added in the mid-90s, when Andrew Motion took up his professorship. Scriptwriting followed a few years after, and Life Writing (part of the Prose strand), came in 2000.

Last night’s voices were as diverse as you would expect: Angus Sinclair read his poetry of assemblages from texts on logic, transforming the language of academe into something delicate, comical and, surprisingly, relevant to an understanding of the world beyond the textbook jargon of the 1960s. The pseudo-Norfolk accent he adopted for his final poem, not in the anthology, remains beyond me. But it was brave.

Another poet, Mona Arshi, shared her self-proclaimed “mid-life crisis poems”, the final line of which – “Here’s my mouth, / hummingbird, linger there, and hold / my breath” – was followed by a shattering of glass as someone stepped on an empty wine glass. It felt right.

From the Prose Fiction category, Claire Powell read her short story “The Girls”, about the relationship between a mother and daughter. It began: “I found them in her bedroom: two black leather legs with a pale chiffon blouse laid out on top of the perfectly spread duvet – an invisible woman sleeping”. From the mother’s arm-band coloured toenails to the tip of her menthol cigarette, the author’s eye for detail is clear. The dialogue, too, is acutely observed, and Powell’s delivery, superb. The final image of the daughter hugging a defunct food blender to her belly as her be-leathered mother dashes off to meet “the girls” in the West End, conveys the narrative’s mixture of comedy and anxiety perfectly. More, please.

Judy O’Kane – a solicitor from Dublin with a qualification from the Wine and Spirit Education Trust, as well as one from the UEA Life Writing course – recounted the events of a previous visit to the very bookshop in which we were crowded. The three minutes ended with her relating her journey home, on the tube, beside a tall, dark, (sort of) stranger, in black tights, with handbag and beard . . . .

Neither the piece nor its continuation is included in the anthology, I'm afraid (a piece called "Rocket House", with a cast of local fishermen, is), but O'Kane succeeded, I’m sure, in enlivening many a ride home last night with the thought of similar close encounters.

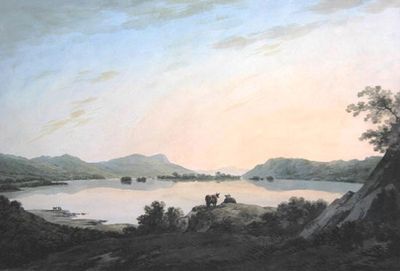

The Lakes before Wordsworth

© Bradford Art Galleries and Museums

By MICHAEL CAINES

In October 1769, only a few months before William Wordsworth was born at Cockermouth, on the edge of the Lake District, another poet made a tour of the area: Thomas Gray, more usually associated with Eton College and a certain churchyard in one of the home counties. It's safe to say that he liked what he saw there. The tourist board ought to take him on – posthumously – as a copy-writer.

Despite the references in his journal and letters to "black & dreary plains" and falling over in a "dirty lane" (a common hiker's complaint), Gray could also write happily about the sublime Helvellyn (that "lofty & very rugged mountain"), the road running along the side of Lake Windermere ("with delicious views across it") and the "stupendous" hills near Cockermouth itself.

October 8, he "mounted an eminence called Castle-rigg, & the sun breaking out discover'd the most enchanting view I have yet seen of the whole valley behind me, the two lakes, the river, the mountains all in their glory. had almost a mind to have gone back again". Helm Crag rears into view, "distinguish'd from its rugged neighbours not so much by its height, as by the strange broken outline of its top, like some gigantic building demolish'd, & the stones that composed it, flung cross each other in wild confusion. just beyond it opens one of the sweetest landscapes, that art ever attempted to imitate . . .".

When Gray wasn't walking around the Lake District or the Scottish Highlands – both expeditions being recorded in Bill Roberts's recently revised edition of Thomas Gray's Journals, published by Northern Academic Press – he was usually to be found in Cambridge, reading. So it is not surprising that, although Roberts's volume contains mainly Gray's own prose, his travels occasionally bring his book-learning to mind. There is a perilous pass where the rocks overhead, "hanging loose & nodding forwards", seem to be "just starting from their base in shivers", first putting him in mind of the Alps ("where the Guides tell you to move on with speed, & say nothing, lest the agitation of the air should loosen the snows above"), and then of Dante's vision of the selfish souls trapped before the Gate of Hell, with no hope of death:

Non ragionam di lor; ma guarda, e passa!

(Let us not speak of them; but look, and pass on!)

This might well be an instance of off-the-cuff erudition on Gray's part, show for the old Cambridge friends he was addressing, but it also puts into perspective his explanatory aside about his diligence in recording place names: "Keswick, Crosthwait-church, & Skiddaw . . . Carf-close-reeds". "I chuse to set down these barbarous names, that any body may enquire on the place, & easily find the particular station, that I mean."

The tourist board should ask Gray's spirit if "barbarous" is intended as a put-down or as a kind of compliment – an expression, that is, in eighteenth-century terms, of a civilized city dweller's excitement at tracing survivals of the past in the apparently ancient names for long-lived settlements and the natural wonders that surround them.

Either way, Gray did his job well: Roberts, for one, has been able to follow his path closely and compare Gray's descriptions with how the scenery looks today, from the A66 to the "modern generation" of Ullswater cormorants.

October 22, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 3

By J. C.

The hebdomadal challenge is to find a neglected work or curiosity by an established author, in one of London’s secondhand bookshops, for about £5. Last Sunday, we stepped on to Hampstead Heath close to where Keats used to play cricket, crossed Kenwood, hoping to avoid the old bletherer Coleridge, finally quitting the sweet pastures for that hideous millionaires’ arcade, the Bishops Avenue. We survived the traffic when crossing Lyttelton Road, ducked under East Finchley railway bridge, and entered Black Gull Books at 121 High Road.

Despite recommendations, we had never visited Black Gull before, and were happy to find it in a reasonable state of what pleases us most: disarray. There are piles of books on the floor, next to boxes of unsorted items – a good sign, for it means the shop is buying (and therefore selling) and that new stock will soon be on display. There is an emphasis on art, with sections for music, history, philosophy, literature, children’s books, etc.

A number of items tempted us, including a hardback of The Rock by T. S. Eliot (1934), which seemed a bargain at £4 until we saw the red inkings. Instead, we chose The Time of the Assassins: A study of Rimbaud by Henry Miller, published in serial form in 1942, and issued as a book in 1956. A TLS reviewer referred to Miller then as “an important bad writer”. More than half a century on, you would be hard pushed to find many in agreement with the first epithet. Once embraced as a pioneer of sexual liberation, he has fallen foul of history and been dumped in the bin of misogyny. Even those with fonder feelings are apt to judge him a windbag.

It has been years since we read Miller, but we would still speak up for Tropic of Cancer, “Via Dieppe-Newhaven”, Quiet Days in Clichy and others. These works had a glad feeling for life on the margins. The Time of the Assassins grew out of a failed attempt to translate Une Saison en Enfer into English. Miller had tried to find a tone close to the blues – as he put it in a phrase sure to displease some readers now, a language “proximate to Rimbaud’s own ‘nigger’ tongue”.

The study of Rimbaud is as much a study of Miller. “When I think of [Rimbaud’s] repeated sallies, like a beleaguered army trying to burst out of the grip in which it is held like a vise, I see my youthful self.” The poet tramping through Germany, Italy, Cyprus, Egypt is but a forerunner of Miller marching “from the heart of Brooklyn to the heart of Manhattan”. The Time of the Assassins gives the impression of having been written in about a fortnight – not always a bad thing. The experience of reading it is like being in conversation with someone who talks rhapsodically, little interested in your response. Our Black Gull find was the seventeenth printing of a New Directions paperback (1962), for which we paid £5.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers