Peter Stothard's Blog, page 68

December 18, 2012

Dreamland in Lyon

By LUCY DALLAS

Earlier this month, the Villa Gillet in Lyon hosted its first non-fiction festival, Mode d'emploi – A user's guide (a typically ambitious, and literary, name, with its nod to Georges Perec's La vie: Mode d'emploi). They conquered New York recently with a series of programmes called Walls and Bridges; their summer festival (Les Assises Internationales du Roman), which deals with fiction, has been successfully running now for six years, so naturally they turned their attention to – well, everything else. There were performances, talks, readings, round tables and conferences on newsworthy topics such as sexual identity and public policy, surveillance and security, climate change and our relationship with the animal world, but there was also room and time for more abstract debates: does democracy work, does evil really exist, does religion make us free? (the latter was co-chaired by the TLS's very own Rupert Shortt).

Taking part in the debate on climate change was Andri Magnason, who crystallized the growing environmental movement in Iceland with his book Dreamland, which made a detailed, passionate, witty case against the installation of more aluminium smelting plants in his country. The smelting takes an enormous amount of energy – cheap and plentiful in Iceland, thanks to the geothermal currents there – and the process, Magnason contends, lays waste to the countryside. It also makes Iceland's economy dependent on huge multinationals, rather than its own people; Dreamland was written before the banking crash and when we talked in Lyon he was happy to report that since then, one of the putative smelting plants has been stopped and more small businesses and start-ups are developing, trusting in their own energy and initiative.

Magnason also made a film of Dreamland and is currently filming again so he could perhaps legitimately be described as an environmental campaigner, or a filmmaker, but writing is at the heart of what he does. He likes to confound expectations of what he will write next, and is keen to avoid being pigeonholed: “I wanted to avoid specification. . . I made myself some kind of a rule, to betray your audience. The only way to serve your audience is to betray it.”

His first book was a volume of poetry published and stocked by one of Iceland's biggest supermarkets, Bónus, easily recognizable with its logo of a pink piggy bank on a bright yellow background; “They have Bónus ham, Bónus cola, Bónus toilet paper, Bónus everything . . . so I was wondering what Bónus poetry would look like.” He made a deal with the owner, who stocked the book in the shops, it was a great success, and since then he has published a science-fiction novel, Lovestar, and a children's book, The Story of the Blue Planet (translated into twenty-three languages, at the last count), both out in English in 2013.

He cites Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Brautigan, George Orwell and Mikhail Bulgakov as literary loves, and there is something of each of these in his work – serious, thoughtful satire and inquiry mixed with humour, dry and daft by turns. Yet despite these international influences, it is rooted firmly in Iceland: “A writer always has to have an anchor somewhere”. And what an anchor: “Global warming, the financial crisis, conglomerate corporations, the literary history – what more could you ask for? It's quite a hotspot. I was in the music hall built right after the crisis and . . .Yoko Ono was giving a peace award to Lady Gaga with our mayor dressed like a Jedi knight, and I was thinking, where else should I be?”

December 15, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 11

By J. C.

The mission is to find a neglected work by an established writer from one of London’s bountiful second-hand bookshops – get thee behind us, Christmas giftbook blues! – for about £5. When, a year ago, we travelled south to Balham to visit My Back Pages on Station Road, our favourable report drew an unfestive response from the owner, Douglas Jeffers. First of all, he wasn’t having any of this “bountiful bookshop” stuff. “‘Bountiful’ is a vile phrase”, said Mr Jeffers, “but let that be . . . .”

He wouldn’t; we were treated to a Balham bashing.

Which we survived, and last weekend braved a return, finding the shop as bountiful as ever. A heavily hatted and coated gentleman, who seemed to have spent the afternoon in the shop, referred to it as “the Aladdin’s cave”. We can do no better. You think you’ve reached the back of My Back Pages and hey presto – another page. Loeb Classical Library mingles with Olympia Press; French and German ally themselves with English; new books stare collectibles in the eye.

My Back Pages would have kept us un-blue through several Christmases. Eventually, we settled for 1919 by John Dos Passos (1932), the second in his great U.S.A. trilogy. We say “great”, but 1919 might seem hard going now, its relentless experimentalism pulling the rug from under realistic narratives about characters such as Ben Compton and Eveline Hutchins. Every twenty pages or so, the famous Newsreel technique breaks out:

it is difficult to realize the colossal scale upon

which Europe will have to borrow in order to

make good the destruction of war

BAGS 28 HUNS SINGLEHANDED

Peace Talk beginning to have its effect

LOCAL BOY CAPTURES OFFICER

There are smiles that make us happy

There are smiles that make us blue

The original Cubist painting must have seemed like this to its original viewer. For those willing to learn its language, however, the U.S.A. trilogy promises substantial rewards.

For this first British edition (Constable), Mr Jeffers charged us £5. Its orange binding with gold-leaf titling is rather bashed about – we know how it feels – but inside we found one of those items which hold a strange attraction. It is a receipt written out to a Mrs Leon of 52 Holland Road, Hove, from the Palmeira Café on Western Road. On July 19, 1941, she read 1919 while enjoying an ice cream at the Palmeira. (Did wartime regulations require the customer’s name and address?) Mrs Leon was charged 1s 10½d. It must have been a high-class ice. In its own way, My Back Pages is a high-class shop.

Perambulatory postscript: readers have asked why publication details of last week’s book, J. P. Donleavy’s Meet My Maker the Mad Molecule, were omitted. It is a firm Penguin of 1971, with a cover by Alan Aldridge. Walden Books charged us £2.

December 11, 2012

Bad Sex at the In and Out

By TOBY LICHTIG

In a publishing year somewhat dominated by Fifty Shades of Grey, it was refreshing to spend a smutty evening putting the literary back into bad sex. The Literary Review's annual Bad Sex Award was set up to "to draw attention to the crude and often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel". With the focus on otherwise decent writing that has been only momentarily besmirched by aberrant filth, there was no room on the list for E. L. James. The illustrious crowd of past-winners includes Sebastian Faulks, Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer, and this year's competition was stiff to say the least.

There were eight contenders on the shortlist at last week's event and several of the offending gobbets of erotic digression were read out with great aplomb by the actors Lucy Beresford and Arthur House to a sniggering crowd at the aptly named In and Out (Naval and Military) Club in Pall Mall. At certain points, the guffaws reached such a crescendo that it almost seemed as if the audience had something to hide.

As the Literary Review's Jonathan Beckman explained in a recent article on the subject, the award is really for bad writing, and euphemistic cliché was a particularly noticeable crime. Ben Masters (Noughties) was probably the worst culprit of this ("she led me to her elfin grot"), closely followed by Paul Mason (Rare Earth), whose sexually charged hero begins "thrusting wildly in the general direction of her chrysanthemum, but missing", while Nicola Barker (The Yips) imagined her character as a "hungry finch" who "has visited the orchard . . . has gorged on the fruit and rejected the pips". Tom Wolfe, meanwhile, in Back to Blood, plumped for an equestrian analogy: "his big generative jockey was inside her pelvic saddle".

Not for the first time in this competition, Craig Raine (The Divine Comedy) made his mark by describing a schoolboy feat of virile bravado (“His ejaculate jumped the length of her arm"), while Sam Wills (The Quiddity of Will Self) came out on top for surreality with this vision of life between the sheets with the Will Self, its prose a homage to the novelist himself: "oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, Will, oh, yes, oh, semen-bedizened blood-pusillanimous bed onanistic quiddity fulcrating pelvic thrusts . . ."). Also on the list was Nicholas Coleridge (The Adventuress: The irresistible rise of Miss Cath Fox), perhaps unfairly nominated for this po-faced scene describing le vice anglais among the aristocracy: "‘Give me no quarter,’ he commanded. ‘Lay it on with all your might.’ Cath did as she was told, swishing the twigs hard onto the royal bottom.”

But the winner of the prize was Nancy Huston (Infrared), for the following carnival of mixed metaphor, fussy digression, erotic cataloguing and freestyle breathlessness:

“He runs his tongue and lips over my breasts, the back of my neck, my toes, my stomach, the countless treasures between my legs, oh the sheer ecstasy of lips and tongues on genitals, either simultaneously or in alternation, never will I tire of that silvery fluidity, my sex swimming in joy like a fish in water, myself freed of both self and other, the quivering sensation, the carnal pink palpitation that detaches you from all colour and all flesh, making you see only stars, constellations, milky ways, propelling you bodiless and soulless into undulating space . . . . “

The novel itself (which will be reviewed in a future edition of the TLS) tells the story of a photographer who takes infrared photographs of her lovers during sex. Huston, who is only the third woman to win in the award's twenty-year history, was magnanimous in victory. Although she was not present to receive the prize, she sent the following message via her agent: "I hope this prize will incite thousands of British women to take close-up photos of their lovers' bodies in all states of array and disarray."

December 8, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 10

By J. C.

To recap: we seek something each week from one of London’s bountiful second-hand bookshops. The guide price is £5. We do not go in search of collectibles, but sometimes find them. . . .

Walden Books in Harmood Street, Camden, is among the pleasantest shops of its kind. Run by the genial David Tobin – last week he told an inquisitive customer he had been there for thirty-three years – it offers a mixture of the rare, the exotic and the commonplace. Paperbacks are ranged outside; there are good literary shelves by the till, a London section, history, music, philosophy and more.

During the hour or so we spent there, passers-by sought refuge from hectic Camden Market; made enquiries; bought books. We pondered the strange case of J. P. Donleavy, a neglected man of modern fiction. Donleavy is an American of Bronx origin. His first novel, The Ginger Man (1955) – no need to be put off by its quondam popularity: it really is good – is set in Dublin. He now lives in a country house near the Irish midlands town of Mullingar. A friend of ours who visited tells us there was only one book in view, though in multiple editions: The Ginger Man. “Donleavy was in great form”, he says, “eager to show off his left hook and his sit-up prowess. He talked much about The Ginger Man, but without the title, referring to it only as ‘the book’.”

He has written a further twenty books, some of which may be unfamiliar: The Lady Who Liked Clean Restrooms, De Alfonce Tennis, Leila. Nothing has lived up to The Book, but in the first ten years of his career Donleavy did have – to adapt the title of his second novel – a singular voice. For some reason, he became attached to alliteration: The Saddest Summer of Samuel S, The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B. We encountered another on Walden’s outdoor stacks: Meet My Maker the Mad Molecule, a collection of stories, most no more than a few pages long, many containing his characteristic verses:

When the going

Is too good

To be true

Reverse course

And beat it.

Perhaps that’s what Donleavy did after The Book. There are other reasons for his fugitive destiny. He became enmeshed in litigation with The Ginger Man’s original publisher, Olympia Press (which he now owns); more deadly by far, he stopped reading. “ I’m not literary in that sense of reading books”, he told our friend. There’s always a price to pay.

December 6, 2012

Good promotions

by Adrian Tahourdin

Here at the TLS we’re used to receiving publicity flyers for forthcoming books, but this week I received a promotional item with a difference: a 30-page pamphlet, printed on high-quality paper, heralding the publication next January of Charles Dantzig’s new book, À propos des chefs-d’oeuvre.

These are tough times in the books trade, but Dantzig’s publishers, the Paris-based Grasset, have pushed the boat out for him. He is clearly a prized author.

Dantzig is something of an original, the author of the wonderfully opinionated and irreverent Dictionnaire égoïste de la littérature française (”Montaigne bores me shitless”), which was a surprise 900-page bestseller in 2005 (the book included a section on “unusual deaths of authors”, broken down into grim categories), as well as the equally successful Pourquoi lire? Why indeed.

The pamphlet starts with a résumé of the new book, in which Dantzig makes the brazen claim that he realized when he had finished the work that it was the first to be written on the subject of literary masterpieces (”sur le chef-d’oeuvre en littérature”) - it’ll be interesting to see how that claim goes down. Taking in Boccaccio to Beckett, Homer to Heine, Petrarch to Pasolini, Dantzig will attempt to define the notion of a masterpiece.

He points out that the sense of the term has shifted from its original meaning. The French Robert dictionary defines it as: “oeuvre capitale et difficile qu’un artisan devait faire pour recevoir la maîtrise dans sa corporation”, i.e. a difficult work that an artisan is expected to complete in order to receive his trade’s qualification. The OED traces the English equivalent, “masterpiece”, to the German “Meisterstück” or Dutch “meesterstuk” — the derivation suggests perhaps that we have traditionally been less comfortable with the concept here than in other European countries.

After that we get choice quotations from the published works, followed by snippets of praise for them, all beautifully laid out — “Charles Dantzig, l’homme-livre”, “Notre Chamfort”, “Un athlète de la littérature”, and a quote that ends “It is clear that Dantzig has read everything”; this was written by me and appeared in something called the “Times Literary Magazine, Londres”.

Dantzig is a master of the pithy insight: for example, we all know that unremarkable novels can make great films but has the reason for this been more eloquently put than Dantzig does here? “In general, average books make very good films: they don’t contain thoughts that the director feels embarrassed at having to suppress.”

As Patrick McGuinness wrote in his TLS review of the Dictionnaire, “Dantzig’s book is an extraordinary undertaking, and anyone who buys it will be happily surprised. Biased, mischievous, provocative, Dantzig is also massively well read, funny and instructive. He is an elegant writer, and is clearly passionate about books”. This quote, needless to say, appears in the pamphlet.

As well as republished interviews and portraits of the author (see above), there are sections on “Dantzig the novelist” and “Dantzig the poet”. The former reveals that he has published five novels as well (how does he find the time?). I read the most recent one, Dans un Avion pour Caracas (2011), with the intention of reviewing it for the TLS, but couldn’t think of anything very positive to say about it; the TLS reviews novels in foreign language very selectively and there didn’t seem to be a case for this one. I came away with a sense that novels are not Dantzig’s forte. Maybe he’ll confound me.

December 1, 2012

How novels are smart

By CATHARINE MORRIS

On Monday Richard Ford

gave a talk written specially for the Royal Society of Literature, to a full

auditorium in Somerset House. His title was “How Novels are Smart”. “I was

going to call it ‘The novelist as intellectual”, he said, “– but then I regained

my senses."

But that was, in fact, his

subject. He started by quoting Umberto Eco’s definition of an intellectual as

“anyone who is creatively producing new knowledge . . . . Critical creativity –

criticizing what we are doing or inventing better ways of doing it – is the

only mark of the intellectual function”. It’s a limited definition, said Ford,

but when he came across it his “ears pricked up”; he thought of novels he had

read. Did fiction produce new knowledge, or invent new ways of doing things?

For Ford himself

writing novels is an “artisanal process” which involves a lot of

“furniture-moving”. He doesn’t always know what he’s doing (which can be

thrilling, he said). He thinks that readers tend to open a novel “with a sense

of grave uncertainty” – they worry that their time will be wasted, or that they

will fail to live up to the book – and look for reasons to stop reading. His

first defence against this is action; “guns going off” etc. ("I’m just a

realist”).

Eco said that “Those

things about which we cannot theorize, we must narrate”. That, according to

Ford, must be the aim of the intellectual writer. Ford also believes that part of

a novelist’s vocation is to do good, and he sympathizes with the idea that

paying close attention to particular “deaths, crimes, joys . . . .” is useful

and life-affirming. Good novels, said Ford, use unexpected, well-chosen words

that show the world in a different light.

We learn about New

England whaling from Moby-Dick, the African diaspora from Richard Wright, the

partition of India from Salman Rushdie, he said. But there is, of course, much

more to it than “supplying info”: “fiction at its most subtle presents the

unseen. It doesn’t reveal what’s there; it invents what was never there . . . .

If that sounds bewildering, it is”. Ford quoted many writers on writing (see a

selection of those quotations at the bottom of this post), and read out

passages from novels that showed “brilliant word choices and emphases” – among

them extracts from Light Years by James Salter (1975), The Transit of Venus by

Shirley Hazzard (1980) and The Master by Colm Tóibín (2004). There were also

these passages by V. S. Naipaul and Jennifer Egan:

"The story she told us

was that her father, a simple serviceman with some factory experience, had had

a fleeting moment of inspiration early in the war. He had hit on a new way of

mounting guns in the tail of an airplane . . . . Always he was on his way to

Ministry of Defense. Ministry of Defense. I heard those words all the time. I

didn’t think she was romancing. Her use of the words ‘Ministry of Defense’

without the definite article – the the that the average person would

have wanted to add – was convincing; it suggested that she knew the words as

well as she had said . . . .” (V. S. Naipaul; from The Enigma of Arrival, 1987;

p77, Vintage)

“. . . . Doll was one

of those people who seem, even to those who knew them well, digitally enhanced:

the bright blond bob cut; the predatory lipstick, the roving, algorithmic eyes

. . . .” (Jennifer Egan; from A Visit from the Goon Squad, 2010; p132,

Anchor)

Ford

concluded that “to define and detail and to push and extend what can be said is

the essential genius in the great novel’s claim to intelligence". But “nothing

is smarter” than revealing your basic artistic impulse – displaying what you

think of as important and interesting enough to share with the reader. “Nothing

a novel does is as profound as taking a risk on its own premiss . . . . All

serious writing starts from within.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

T. S. Eliot (from

“East Coker”, 1940): “each new venture / Is a new beginning, a raid on the

inarticulate / With shabby equipment always deteriorating / In the general mess

of imprecision of feeling”.

Martin Amis (from an essay published in the New

York Times):

“The day-to-day business of writing a novel often seems to consist of nothing

but decisions – decisions, decisions,

decisions. Should this paragraph go here? Or should it go there? Can that chunk

of exposition be diversified by dialogue? At what point does this information

need to be revealed? . . . These decisions are minor, clearly enough, and they

are processed more or less rationally by the conscious mind. All the major

decisions, by contrast, have been reached before you sit down at your desk; and

they involve not a moment’s thought.”

Henry James (from the preface to The Princess

Casamassima, 1886): “It seems probable that if we were never bewildered there

would never be a story to tell about us”.

Walter Benjamin (from

his essay “The Storyteller”, published in Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 1968): “To write a

novel means to carry the incommensurable to extremes in the representation of

human life.”

Randall Jarrell (from the preface to The Man Who Loved Children by

Christina Stead, 1965 edition): “A novel is a prose narrative of some length

that has something wrong with it."

Photograph by Laura Wilson

November 30, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 9

By J. C.

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 6th series, part IX. For the past five years, the TLS editorial offices have been situated in Bloomsbury, close to a warming huddle of bookshops. Next week, however, we remove to Wapping. (The postal address of the TLS remains unchanged.) It was a melancholic perambulation, therefore, that took us on a tour, arriving first at Skoob Books, a shop much patronized by students. . . .

The staff have a reputation for severity, and could perhaps learn from the smiling toilers at neighbouring Waitrose supermarket, but last week a young man responded sympathetically to an older gentleman with a stick seeking advice on publishing his poems; and the sound of a customer tumbling down the stairs (unharmed) brought a concerned look to the face of his boss.

Earlier this year, we drew attention to the centenary of Lawrence Durrell (1912–90), once a strong force in mid-century English letters but neglected now. At Skoob, we lighted on a curiosity: The Dark Labyrinth, first published as Cefalû in 1947 and reissued in an Ace Books edition in 1958. The story, set in Crete after the war, involves “a party of sightseers . . . trapped in what was then the newly-discovered labyrinth of Cefalû”. Among them is one Captain Baird, who was “in charge of some guerillas” on the island during the Resistance. Having just read the essay by Simon Fenwick (TLS, November 16) about the friendship between Durrell and Patrick Leigh Fermor, we cannot help wondering if Captain Baird bears some relation to Major Fermor. We will read on to find out. For this tattered Ace, a first thus, we paid £5.

Around the corner in Marchmont Street is Gay’s the Word. We’re happy to see it still there, but nonetheless wonder what its role is now, when all bookshops have Gay sections, except those which abjure segregation. In the window were books by Ginsberg, Isherwood and Frank O’Hara. On we went, passing Judd Books, a few doors down. It specializes in remainders but also has secondhand stock.

Collinge & Clark, a small specialist art and literature shop in Leigh Street, has a tempting outside barrow, and here we unearthed a copy of Kingdom Come, the first literary journal to appear in Britain after the start of the Second World War. The editors were themselves belligerent. Neville Coghill scolded T. S. Eliot, whose East Coker had lately appeared. To Coghill, the “go into the dark” passage “imitates, without improvement, one of the finest speeches in Samson Agonistes . . . . It is a pity that by inviting comparison Eliot should draw attention to his inferiority”. Geoffrey Grigson kicks Walter de la Mare on the backside with one of his country walking boots (“too exclusively open to literature, which he mistakes for the world”), reserving the other for Stephen Spender. In a poem, Hugh MacDiarmid is on the brink of joining the Soviet ranks to hasten the demise of the bourgeois West. Sets of Kingdom Come change hands for serious prices; for this issue, with a cover by Baptista Gilliat-Smith, C&C charged us £4. We will miss these neighbours. The consolation is that Arthur Rimbaud went to Wapping before us (and travelled by Tube: see Les Illuminations, XXVIII).

November 29, 2012

Books of the year, from love to hate – and from Zoffany to Acceptance

By MICHAEL CAINES

This week's issue of the TLS devotes several pages to the generally positive exercise that is "Books of the Year" (or "International Books of the Year", depending on who you ask; the adjective emphasizes an notable aspect of our contributors' wide reading). I say "generally positive" because you do sometimes learn a bit about what writers, scholars, scientists, artists et al dislike as much as what they like.

For example . . .

Katherine Duncan-Jones is happy to have read Merivel, Rose Tremain's sequel to Restoration, and learned to love the historical novel, because the "garrulous and slow-paced" works of Sir Walter Scott had previously bored her "almost to screaming". (In terms of the longer, meandering course of literary history, Scott seems to have long ago turned into a kind of oxbow lake – redundant, sadly for his true admirers, but vital to its development.)

Or there's Hilary Mantel, confessing that Edna O’Brien's memoir Country Girl exerted a "loathly grip" on her, despite being neither a great book "or even a good one".

Among the usual displays of taste and erudition, distaste makes itself known less directly, and we've put a selection from the selection online – from Mary Beard's plea for exhibition catalogues, inspired by the excellent accompaniment to this year's Zoffany exhibition at the RA, to Rowan Williams's last contribution in his time as Archbishop of Canterbury, on a powerful book that offers "nothing easily consoling . . . but rather a sense of stillness, acceptance and hope" – so you can see for yourself the range of what's been published (or, in some cases, what's only now been read) and make your own deductions, compare notes, violently disagree, etc.

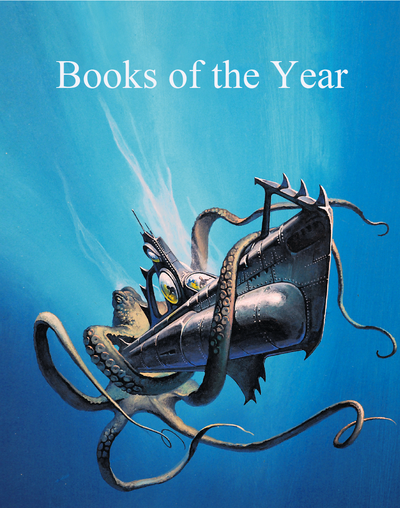

It's also a flimsy excuse for me to publish this variation on our cover. Above is a mighty illustration by Gino D'Achille to Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, chosen on account of Peter Cogman's piece on Jules Verne's Voyages extraordinaires finally finding their way into the Pléiade, that seems to have shifted dimensions and become, in the process, an illustration of the critical process – a reader hitching a bookish ride? Or – a more "loathly" possibility, perhaps – is this a "Book of Year" taking possession of some unwilling literary submariner?

There is another general point to be made about these choices, and the Editor has already made it in his weekly introduction to the issue, confirming a couple of points about judging this year's Booker Prize along the way.

November 23, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 8

By J. C.

Some weeks ago, the TLS published a letter from a reader in Florida who, having read here about the Keith Fawkes bookshop in Hampstead, known as the Flask, “was prompted to visit the establishment”. Not only did she find the book she was looking for – Gissing’s In the Year of Jubilee – but she had “a lovely discussion about literature with the kind gentleman in charge that day”.

We know that gentleman, willing and able to discuss a wide range of literary topics, and we looked forward to something of the kind last week. What a shock, then, to find the Flask’s interior invaded by bric-a-brac from the flea market that now buzzes about its door. . . .

A year or so ago, half the shop was given over to storage from the jumble sale; then a bit more; now only about 25 per cent of the floor space is allotted to books. Customers trickle in. “You’re the Tennyson man”, the kind gentleman says to one; another locates a desired chess book; yet another seeks Wuthering Heights. It’s here somewhere, under the old glass, china and fraying curtains. But how to get there? The novice Brontëan leaves disappointed.

It seemed somehow suitable that we should light on the works of a poet who himself was once in danger of being submerged: Andrei Voznesensky came to the attention of Western readers in the early 1960s, following a path cleared by Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Although the pair were born in the same year, 1933, Voznesensky seemed younger. Yevtushenko was photographed with President Nixon, while his compatriot posed with Allen Ginsberg. Yet he was known as a formalist. In the preface to a volume translated by various hands, Antiworlds (OUP, 1967), W. H. Auden praised Voznesensky’s craftsmanship. “Here is a poet who knows that . . . a poem is a verbal artifact which must be as skilfully and solidly constructed as a table”.

In the Flask, we unearthed one of those lovely floppy Grove Press paperbacks from the 1960s, Selected Poems, translated by Anselm Hollo, with a cover by Roy Kuhlman. The contents overlap with those of Antiworlds, but at times you would scarcely know it. “Ballad of 1941”, the year Germany invaded the Soviet Union, opens in a version by Stanley Moss: “The piano has crawled underground. Hauled / In for firewood, sprawled / With frozen barrels, crates, and sticks, / The piano is waiting for the ax”.

Turning to Hollo, we find: “The piano has disappeared into the quarry, / It was dragged down to the firewood store: / Frozen vats and boxes of chaff. / Now it was waiting / for the breaker’s ax”. Moss structures the ballad in quatrains, with passable rhymes. Hollo dispenses with form, and chucks in an ending which might or might not derive from the original (if it does, it was missed by Moss). So much for craft. Still, we are pleased to have liberated Voznesensky from the siege of Flask Walk. For Selected Poems, the kind gentleman divested us of “all of £2”.

November 19, 2012

How to advertise Asterix

By MICHAEL CAINES

As mentioned before on this blog, the business of selling books encourages some curious habits – relying time and again on the same old cover designs, or, when reissuing a forgotten "modern classic", finding an unforgotten name to offer a line or two of endorsement. It's striking how small a part words themselves play in this aspect of publishing.

See above and below for a contrasting example of the art of the book advertisement, for the Asterix books of René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. They appear on opposing pages of the TLS of October 16, 1969 (a time when the paper still reviewed children's books). Aren't they – busy? And cheeky, too: "We have paid for them!".

But perhaps in the end this proved to be no way to persuade people that the "strip cartoon can be a genuine art form". It's a while since anybody took out an advertisement in the TLS that looked like this . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers