How novels are smart

By CATHARINE MORRIS

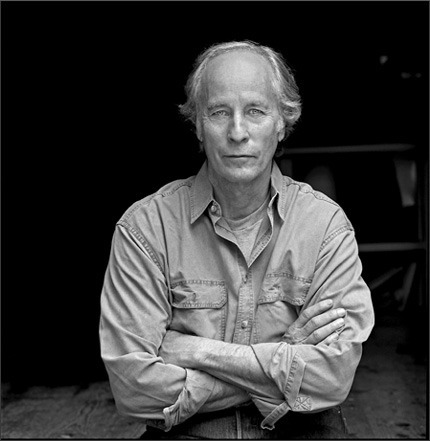

On Monday Richard Ford

gave a talk written specially for the Royal Society of Literature, to a full

auditorium in Somerset House. His title was “How Novels are Smart”. “I was

going to call it ‘The novelist as intellectual”, he said, “– but then I regained

my senses."

But that was, in fact, his

subject. He started by quoting Umberto Eco’s definition of an intellectual as

“anyone who is creatively producing new knowledge . . . . Critical creativity –

criticizing what we are doing or inventing better ways of doing it – is the

only mark of the intellectual function”. It’s a limited definition, said Ford,

but when he came across it his “ears pricked up”; he thought of novels he had

read. Did fiction produce new knowledge, or invent new ways of doing things?

For Ford himself

writing novels is an “artisanal process” which involves a lot of

“furniture-moving”. He doesn’t always know what he’s doing (which can be

thrilling, he said). He thinks that readers tend to open a novel “with a sense

of grave uncertainty” – they worry that their time will be wasted, or that they

will fail to live up to the book – and look for reasons to stop reading. His

first defence against this is action; “guns going off” etc. ("I’m just a

realist”).

Eco said that “Those

things about which we cannot theorize, we must narrate”. That, according to

Ford, must be the aim of the intellectual writer. Ford also believes that part of

a novelist’s vocation is to do good, and he sympathizes with the idea that

paying close attention to particular “deaths, crimes, joys . . . .” is useful

and life-affirming. Good novels, said Ford, use unexpected, well-chosen words

that show the world in a different light.

We learn about New

England whaling from Moby-Dick, the African diaspora from Richard Wright, the

partition of India from Salman Rushdie, he said. But there is, of course, much

more to it than “supplying info”: “fiction at its most subtle presents the

unseen. It doesn’t reveal what’s there; it invents what was never there . . . .

If that sounds bewildering, it is”. Ford quoted many writers on writing (see a

selection of those quotations at the bottom of this post), and read out

passages from novels that showed “brilliant word choices and emphases” – among

them extracts from Light Years by James Salter (1975), The Transit of Venus by

Shirley Hazzard (1980) and The Master by Colm Tóibín (2004). There were also

these passages by V. S. Naipaul and Jennifer Egan:

"The story she told us

was that her father, a simple serviceman with some factory experience, had had

a fleeting moment of inspiration early in the war. He had hit on a new way of

mounting guns in the tail of an airplane . . . . Always he was on his way to

Ministry of Defense. Ministry of Defense. I heard those words all the time. I

didn’t think she was romancing. Her use of the words ‘Ministry of Defense’

without the definite article – the the that the average person would

have wanted to add – was convincing; it suggested that she knew the words as

well as she had said . . . .” (V. S. Naipaul; from The Enigma of Arrival, 1987;

p77, Vintage)

“. . . . Doll was one

of those people who seem, even to those who knew them well, digitally enhanced:

the bright blond bob cut; the predatory lipstick, the roving, algorithmic eyes

. . . .” (Jennifer Egan; from A Visit from the Goon Squad, 2010; p132,

Anchor)

Ford

concluded that “to define and detail and to push and extend what can be said is

the essential genius in the great novel’s claim to intelligence". But “nothing

is smarter” than revealing your basic artistic impulse – displaying what you

think of as important and interesting enough to share with the reader. “Nothing

a novel does is as profound as taking a risk on its own premiss . . . . All

serious writing starts from within.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

T. S. Eliot (from

“East Coker”, 1940): “each new venture / Is a new beginning, a raid on the

inarticulate / With shabby equipment always deteriorating / In the general mess

of imprecision of feeling”.

Martin Amis (from an essay published in the New

York Times):

“The day-to-day business of writing a novel often seems to consist of nothing

but decisions – decisions, decisions,

decisions. Should this paragraph go here? Or should it go there? Can that chunk

of exposition be diversified by dialogue? At what point does this information

need to be revealed? . . . These decisions are minor, clearly enough, and they

are processed more or less rationally by the conscious mind. All the major

decisions, by contrast, have been reached before you sit down at your desk; and

they involve not a moment’s thought.”

Henry James (from the preface to The Princess

Casamassima, 1886): “It seems probable that if we were never bewildered there

would never be a story to tell about us”.

Walter Benjamin (from

his essay “The Storyteller”, published in Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 1968): “To write a

novel means to carry the incommensurable to extremes in the representation of

human life.”

Randall Jarrell (from the preface to The Man Who Loved Children by

Christina Stead, 1965 edition): “A novel is a prose narrative of some length

that has something wrong with it."

Photograph by Laura Wilson

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers