Peter Stothard's Blog, page 64

March 25, 2013

The People of the App

by TOBY LICHTIG

Tonight is Passover, a festival that has gone through various transformations in its three-thousand-year history. I'm not sure whether the first generation of celebrants descended from the slaves who fled Pharaoh's Egypt would have recognized cupboards swept clean of flour, children hunting for pieces of unleavened bread under sofa cushions, and representations of gruesome plagues in the form of finger puppets. But one of the things that helps a religious ritual to endure is its ability to move with the times.

Passover is a great story, full of tragedy, gore and vengeful triumph against the odds. And like all good stories, it has continued to evolve. Now it has gone virtual. The Haggadah – the 2,500 year-old text that describes the tale of the exodus and gives instructions for the order of the Seder – is available in app form.

The Haggadah App (Haggadap?) comes in "modern" and "traditional" Sephardi and Ashkenazi versions, and includes songs, pictures and videos.

The app, say the developers, is "an interactive and fully customisable e-book, created to help people of any level of religious knowledge or observance to prepare for the Seder and help them clearly explain the traditions to all participants".

Observers, or rather "users", are able to tailor the e-Haggadah "so that the running time is adjusted to their needs". They are also able to adjust the religiosity, making this suitable for revellers from "any kind of Jewish background".

While this venture is to be lauded for its enterprise and plurality, parents struggling to bar their children from hand-held devices at the dinner table may be rather less impressed. Confronted with the question "Why is this night different from all other nights?", some may be tempted to answer, "it isn't".

March 22, 2013

A Britten top ten

By MICHAEL CAINES

Here’s an aside to Ian Bostridge’s magisterial overview, in this week’s TLS, of several new books published to mark the centenary of Benjamin Britten’s birth. The YouTube-illustrated list below represents what one of those books reckons to be the current “Britten Top Ten” – ie, a list of his ten pieces that are “most popular with the public at large”:

1 The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

2 Four Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes

3 A Ceremony of Carols (so good he posted it twice, if only for the costumes, and the contrast between soprano and treble soloists)

4 Simple Symphony

5 Serenade for tenor, horn and strings

6 Soirées Musicales (intially taken here at quite a lick, as befits a precocious early suite inspired by Rossini)

7 “The Foggy, Foggy Dew”

8 A Hymn to the Virgin

9 “The Salley Gardens”

10 "Tell Me the Truth about Love" (the opening flourish puts me off this one – possibly a silly prejudice on my part . . .)

The source for this list is what used to be The Faber Pocket Guide to Britten by John Bridcut, first published in 2010, and now revised and elevated to the rank of Essential Britten. It’s a “delightful” compendium, according to our reviewer. There’s much more to the composer’s achievements, however, than the popular pieces mentioned above, as Bridcut is quick to point out. It contains “four or five indisputable masterpieces”, he says (although here he doesn’t say which ones; any guesses?), but it only covers “the first half of Britten’s composing life, and includes nothing sung in his fifteen operatic works”.

Funny he should mention that. This summer the Royal Opera House will tackle one of the most notoriously unpopular of those later operatic works: Gloriana, which seems to have discomforted its first audiences, in the Coronation year of 1953, by looking “beyond the cliché of the Elizabethan past as source of renewal”, as Ian Bostridge puts it, “to a more troubling mapping of that past on to the Elizabethan present”. Is this wise? Given the strength of feeling recently expressed against a mere novelist for daring to speak a troubling word or two about the Duchess of Cambridge, I’m not sure we Brits are ready to look beyond Britten’s top ten. . . .

March 21, 2013

Celebrating Benjamin Britten, Cyber-stalking and James Lasdun, and J. M. Coetzee’s new world

In this week's TLS – A note from the Deputy Editor

“The public face of classical music in Welfare State Britain”, Benjamin Britten hobnobbed with the Queen Mother, wrote an enormous, expensive grand opera to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, accepted a life peerage and appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Yet he retained a “resolutely workaday” musical philosophy, “concerned with usefulness to the community”, and consciously distanced himself from Romantic notions of greatness. Even at the height of Britten’s fame his work had its critics and its doubters, as it does today, in his centenary year; Ian Bostridge, the tenor renowned among other things for his interpretations of Britten’s vocal repertoire, puts the case for its enduring power.

In both his work and life Britten “swerved instinctively away from the centre ground”, not least in his homosexuality. Performing his settings of same-sex love poems with his partner Peter Pears was, he said, “rather like parading naked in public”. Bostridge reminds us that, though Britten and Pears were tacitly received everywhere as a couple, in 1954 over 1,000 men were in prison for homosexual offences. The poet and novelist James Lasdun had committed no offence beyond a “mildly flirtatious” exchange of emails with one of his creative writing students when he found himself being cyber-stalked and cyber-bullied. As “Nasreen”’s emails grew more abusive and threatening, Lasdun decided he had to fight back. His memoir of the episode, “an elaborate tale of psychological warfare and survival”, is reviewed by Elaine Showalter. Ten years ago, with his novel about a paranoid professor who believes he is being persecuted by women, Lasdun joined a distinguished company of writers in a sub-genre involving accusations of sexual misconduct that includes David Mamet, Philip Roth and J. M. Coetzee. Coetzee’s latest novel postulates a “new world” that resembles a socialist utopia, whose inhabitants are strangers to sex, irony and salt; a world in which “God and the truth are merely the storyteller’s playthings”, according to Edmund Gordon.

Alan Jenkins

March 17, 2013

English as she isn't spoke

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Genteelisms are a curse of modern life. The announcements on railway platforms and trains that many of us are subjected to most days are a particular case in point. I’m referring to such constructions as “We are sorry for the delay to your journey. This is due to a fault on a preceding train that cannot be rectified”. Preceding? Rectified? Does anyone use such words in spoken as opposed to written English? It’s a form of genteelism, born from a sense that plain words, such as earlier for “preceding” and fixed for “rectified”, are somehow not good enough.

The battle against the hideous use of the word “customer” to denote a passenger has long ago been lost. We are all customers on trains, enjoying the service being provided rather than merely getting from A to B. “Will customers standing please move down the carriage to allow other customers to get on” neatly encapsulates the absurdity of it. Some train guards persist, during their on-board announcements, in correctly addressing us as “passengers”; let’s hope their words aren’t recorded or they’ll probably be sent off for a re-education programme. (I should say that train guards, ticket inspectors - sorry, “revenue collection officers” - and platform staff are almost unfailingly polite and friendly; it’s not about them.)

Yet when there’s an incident on a train involving “customers”, I’ve noticed that they tend to be downgraded to passengers, as in “this is due to a passenger being taken ill on the train” or “due to passengers fighting in the Clapham Junction area” (ok, I made up the last one, but it’s broadly representative). Yes, they’re very keen on the word “due”.

On it goes: “Please be advised that this service has been cancelled”. Or “It has become necessary to cancel this train”. “Train doors may close 30 seconds prior to booked departure time”, and so on. “Prior to” is always a good unnecessary variant for “before”. Trains are “subjected to platform alterations” - poor trains.

I travel on the Brighton to London line, which is in the hands of two companies, Southern and First Capital Connect (or Disconnect, as I prefer to call it). Journey time from London to Brighton is less than an hour, yet you still hear announcements apologizing for the fact that “there is no first class accommodation on this train” - er, what would that be? Sleeping cars? Couchettes? On a 50-minute journey? Rather than “accommodation” do they mean seating perhaps. After all, why use a two-syllable word when you can shoehorn in a five-syllable one? Sounds posher, doesn’t it? These are all recorded

announcements, so they have the official seal of approval of the train company.

Does any of this matter? Well, it matters to me, clearly. I also think it does because, aside from the irritation it provokes, such corporate misuse of language - or call it a clumsy attempt to shield simple truths behind a fog of verbiage - speaks of a kind of contempt for the public. And that does matter.

March 15, 2013

Peter Ackroyd at the Beinecke Library

By CATHARINE MORRIS

All of a sudden I want to go to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale. I hadn’t realized how spectacular it is: geometric marble and granite on the outside, and inside a massive soaring tower of bookcases encased in glass. And then there are the collections – ancient papyri, a Gutenberg Bible, Ezra Pound papers, Tocqueville manuscripts, Boswell family correspondence, the Mellon Chansonnier, sixteenth-century portolan charts, Alfred Stieglitz autochromes, a Gertrude Stein home movie . . . .

It was founded in 1963 by three brothers “linked from their earliest years by a deep affection, shared interests, and complementary though different talents and personalities”. It is celebrating its fiftieth birthday in style, as you might imagine, with a year-long programme of exhibitions, lectures, readings, concerts and conferences. Last week it honoured its international reach (it is open not just to its own students but to writers and researchers from all over the world) with a reception at the Athenaeum in London. Peter Ackroyd had been asked to say a few words about his own experiences at the library in the 1970s, when he was gathering material for his book on Modernism, Notes for a New Culture (1976; you can read the TLS's review of it here).

His first reaction to the building, he remembered, was surprise and admiration. “I wasn’t sure what it was. It was rather disorientating.” Nearby at that time was a sculpture by Claes Oldenburg of a cannon with a lipstick attached to it, which “added to a surreal Alice in Wonderland feel”. But the windows, he said, “shone with the light of interior knowledge . . . . The staff were as knowledgeable as any I have come across”. Judging by the atmosphere at the reception, its staff are also among the friendliest. Perhaps they are also among the most amusing. Ackroyd told us that when the library added his own papers to its collections – “much to my delight and pleasure” – he asked when the papers would be catalogued, and the conversation went on like this:

“Only when you’re dead.”

“I’ll let you know.”

“Don’t call us – we’ll call you.”

Top: Photograph by Alexandra Cavoulacos

March 14, 2013

Habemus Papam!

By RUPERT SHORTT

Pope Francis I has many strengths, including a humble streak, a degree in chemistry, and a burning commitment to fighting poverty. He moved from the archbishop’s palace in Buenos Aires into a small flat, and used public transport instead of a limousine.

As a pastoral bishop from outside Europe rather than a Vatican insider, he will know more than the other-wordly Benedict XVI about the lives of grassroots Catholics. Like his predecessor, though, the new Pope is intensely conservative on sexual morality, and has prompted complaints from politicians in the past for condemning gay marriage so fiercely.

He takes over a Church in crisis, and it will be a while before we can judge whether the conclave has elected a man equal to the challenges ahead.

Consider the following damning statements. “The Catholic Church is 200 years behind the times”. The scandal of paedophile priests should lead to a “transformation” in the way the organization is run. More broadly, the Church should “admit its errors” and introduce radical change, “starting with the Pope”.

These words come not from one of the usual suspects, but from Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, who died last year and would himself have made a great reforming Pope.

Martini understood the crying need for greater transparency in the way the Catholic Church is run.

The world’s largest association is in so many ways a massive force for good. It is the biggest single supplier of healthcare and education on the planet. Visit the poorest places on earth, and you’re likely to find lay Catholics, nuns or priests supporting the most vulnerable. Their fellow believers champion the common good in a host of other situations.

But the contrast between heroism on the ground and the Vatican, which even Pope Benedict admitted to be riven by cliques and careerists, is glaring.

Fifty years ago, the Catholic Church reformed itself during and after the Second Vatican Council. Having previously turned its back on the world, condemning scientific developments, democracy and women’s rights, the Church began a grown-up conversation with modern society. The principle of “collegiality” – a technical term for teamwork – was championed.

Tragically, however, the revolution was stopped in its tracks – and then reversed – by Pope John Paul II. Strict central controls were reaffirmed, and with them the unaccountable power structures that had long blighted the Church’s reputation.

The joint architect of this regression was none other than Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Benedict XVI. On becoming Pope himself eight years ago, he allowed a bad situation to fester. The absolute ban on artificial birth control was reaffirmed, as were the celibacy rule, the denial of Communion to remarried divorcees, and other teachings judged to be pastorally insensitive or incoherent by many. Catholics were banned from even discussing matters such as the ordination of women.

There is a link between such authoritarianism and the perverse management style that allowed paedophilia – along with other scandals, financial as well as sexual – to develop unchecked. So in addition to cleaning up the mess on his doorstep, Pope Francis would do well to introduce a more inclusive style of leadership overall. I hope that’s why the cardinals elected him.

March 13, 2013

William Styron, David Foster Wallace, and a “snapshot of pure happiness”

In this week's TLS – A note from the Editor

William Styron died long before the days of blogging and Twitter. But had the author of The Confessions of Nat Turner faced the firing squads of modern times, it would not have been a pretty sight. In 1968, his bestselling re-creation of a slave hero merely roused ten black writers to publish a book of their own: “one long hysterical polemic from beginning to end”, Styron wrote in a letter to one of his former teachers. “Pure racism” was the response of one objector to the idea that Turner had “an uncontrollable desire to violate a white woman”. Styron’s attitude to African Americans changed thereafter, writes James Campbell, reviewing the selected letters of a slow-writing anglophobe with the acutest sensitivity to criticism of every kind.

David Foster Wallace famously shared with Styron the stimulus and curse of depression. His writing about the condition and its treatments was some of his best work. As Thomas Meaney describes this week, reviewing three new books on the writer, a short story from 1998, “The Depressed Person”, goes to the heart of Wallace’s work, and not just because we know now about his road to suicide a decade later. Meaney wonders whether ambitious young writers of the future will stick by Wallace or not, an artist who “demands a willingness to dirty your hands in the culture and to swallow boredom whole”.

Christopher Cusack considers the “booming business” in books about the “Great Irish Famine”, a topic in which political and historical controversy have long been mixed. A new atlas of mid-nineteenth-century Ireland includes maps and essays showing the differfent attitudes on opposite sides of the Irish Sea. The blight-prone potato was a sensible staple food for those who grew it, a symbol of indolence and bad character to those who ruled them. Historical analysis has made significant advance but interest in the Famine is still “entangled in its own rhetoric”.

Ruth Scurr praises a “snapshot of pure happiness” at the end of the myriad narratives in Life After Life by Kate Atkinson.

Peter Stothard

March 12, 2013

News from the eighteenth century

By MICHAEL CAINES

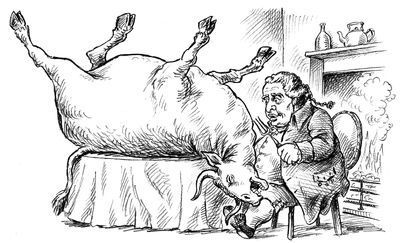

The eighteenth century is good for a laugh – at least according to the Gin Lane Gazette. See above for an example: here’s the Duke of Norfolk sizing up his somewhat raw-looking main course. This “vulgar, heavy, clumsy, dirty-looking Mass of Matter” (meaning the Duke rather than his dinner) apparently holds a record for a member of that terribly eighteenth-century confraternity, the Sublime Society of Beef-Steaks, “by consuming an astonishing Fifteen Steaks” at one sitting. “He has a Capacity for Liquor as great as his Appetite for Victuals”; when he inevitably passes out as a result of his exertions, four servants carry him away to bed, and sometimes take advantage of the situation to clean him up, something he seemingly cannot do for himself.

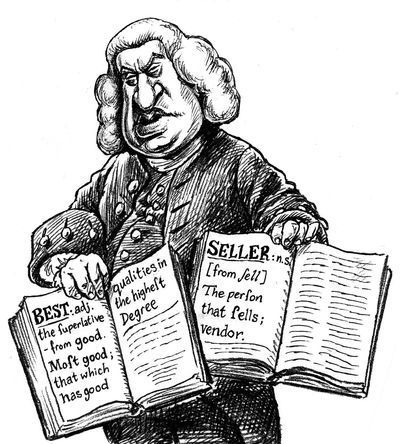

The work of the cartoonist Adrian Teal, the Gazette is a busy confection of similarly outlandish stories, with plenty of cheekily bared body parts, posturing duellists, hapless politicians and prodigies of nature. (The caricature of Norfolk, naturally enough, belies his significance as a patron of the arts and politician.) On one page, Dr Johnson appears in a pseudo-publicity shot for his long-awaited Dictionary of the English Language (as below); over the page, he's offering a certain crude salute to Jonas Hanway, the author of An Essay on Tea to which the lexicographer took exception.

Even without Teal’s colourful (or rather, apart from the cover, black-and-white-and-red) views of the past, the message is clear. These people lived bizarre lives – as readers of popular histories of Georgian England have long thought. They resemble their descendants in certain respects, conveniently enough; in others, they are in a world of their own.

This world is peopled with absurdities. Would a theatrical satirist who lost a leg and gained a theatre as a result of a riding accident in the presence of a prince amuse you? Look no further than Mr Foote’s Other Leg. Or how about an anti-slavery campaigner who secretly adopted two orphan girls, in the hope that one of them would grow up to be his ideal woman? Try Wendy Moore’s How To Create the Perfect Wife (a book I recently reviewed for the Wall Street Journal). Doctors who killed (as in Roy Porter’s Quacks) and women who dressed as men and joined the Navy (as in S. J. Stark’s Female Tars)? It’s all good eighteenth-century fun, apparently – and it looks only a little odd as translated by Teal into the language and look of a fictional newspaper from the period.

Appropriately, the Gazette has come into being in an old way made new: readers pledged their support for its publication via the Unbound website, and are duly listed as “subscribers” at the back of the finished book. Anybody feeling sufficiently Georgian may go through the list looking for grandees, and, in their apparent absence, will have to console themselves with the presence of some scholars of the period and Haven Risk Management.

They might also note, as they flick the page one way, that Teal has wisely adopted the long “s” in order to “celebrate some of the lost qualities of times past”, and, flicking back, that there’s a page acknowledging the “invaluable” assistance of secondary sources ranging from Mr Bligh’s Bad Language by Greg Dening to Christopher Hibbert’s King Mob and Katie Hickman’s Courtesans – a piece of academic diligence which was not so common a feature of the period. (It’s a bit misleading, though, to date T. H. White’s more sophisticated essay on the same theme, The Age of Scandal, to 2000, fifty years after its first publication).

There’ll be a review in the TLS soon of two books about Dr Johnson that show Gazette-worthy quaintness and a contrasting intellectual magnificence combined in that single figure. And I suspect that sooner or later we might find ourselves reviewing yet another book about one of those “Ladies of Fashion” who so delight Teal – those ladies who “insist upon perpetuating their slavish Devotion to Finery of prodigious & ridiculous Dimensions” at “Routs, Levees, & Balls”, where they sport “phantastickal Decorations”, including “miniature Ships, arrangements of Fruits & Feathers, & Birds who appear to have made their Homes atop their towering Tresses”.

“We hear often of Ladies who are oblig’d to sit upon the floors of their Carriages, so tall are the Adornments perch’d upon their Scalps. . . .”

March 11, 2013

Flaubert biographies

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This is Flaubert, of

course, in a copy by Caroline Franklin-Grout of an etching by Eugène

Champollion. It adorns the cover of Michel Winock’s new biography of the

writer, published by Gallimard. Franklin-Grout was the writer’s niece.

In Flaubert’s Parrot, Julian

Barnes’s protagonist Geoffrey Braithwaite, a retired doctor, widower and

amateur Flaubert enthusiast, spends a chapter demolishing Enid Starkie’s

biography of the writer. He points out that in the first volume (1967), Starkie

chose as the “frontispiece” a portrait of “Gustave Flaubert by an unknown

artist”. “The only trouble is, it isn’t him. It’s a portrait of Louis Bouilhet

. . .”. Bouilhet was a minor poet and dramatist, and a contemporary and close

friend of Flaubert.

Braithwaite goes on to

say: “I once heard Dr Starkie lecture, and I’m glad to report that she had an

atrocious French accent” (Starkie taught at Oxford). In a chapter entitled “Emma

Bovary’s Eyes”, he quotes from the biography: “Flaubert does not build up his

characters, as did Balzac, by objective, external description; in fact, so

careless is he of their outward appearance that on one occasion he gives Emma brown

eyes (14); on another deep black eyes (15); and on another blue eyes (16)”.

Flaubert actually wrote:

“quoiqu’ils

fussent bruns, ils semblaient noirs à cause des cils . . .”, and later: “Vus de

si près, ses yeux lui paraissaient agrandis, surtout quand elle ouvrait

plusieurs fois de suite ses paupières en s’éveillant; noirs à l’ombre et bleu

foncé au grand jour, ils avaient comme des couches de couleurs . . . ”. (". . . brown eyes, but made to look black by their dark lashes . . . "; "Seen so close, her eyes appeared enlarged, especially when she blinked them open several times in succession on waking. Black in the shadow, and a rich blue in broad daylight, they seemed to hold successive layers of colour, , . . " Alan Russell's translation)

Hardly "careless".

The killer lines come at the end of the chapter: “All in all, it seems a magisterial negligence

towards a writer who must, one way or another, have paid a lot of her gas

bills”.

“Why write a biography

of Flaubert? One more . . . ”, asks Michel Winock in his preface. Winock claims

no expertise when it comes to Flaubert – he’s an intellectual historian – and

craves the indulgence of Flaubertians. Yet he relates how when he was studying at

the Sorbonne, he and his fellow students would wander over to the Luxembourg

Gardens where they’d recite whole passages from L’Éducation sentimentale to

each other.

Winock follows on the

heels of Geoffrey Wall's biography of 2001, which the TLS reviewer

Maya Slater described as “magnificently readable” if light on the work itself (October 10, 2001).

More recently, Frederick Brown published a 650-page Life in 2006, which the TLS reviewer Victor Brombert commended for its "impressive capacity for documentation", and its "literary flair and restraint" (September 1, 2006). Brombert points out that Brown has made "especially good use of the extraordinary letters that Flaubert wrote . . . ". See Julian Barnes's review of the fifth and final volume of the letters.

It remains to be seen whether

Winock has managed to come up with anything new, although he claims to bring a

historian’s perspective to bear. He has provided a “Petite anthologie” of

Flaubertian wisdom, from “Absolu” to “Vérité”: e.g. under Avenir: “L’avenir est

ce qu’il y a de pire, dans le présent” (1839); Gens de lettres: “Les gens de

lettres sont des putains qui finissent par ne plus jouir” (1852); Haine: “La

Haine est une vertu” (1872); Style: “Que je crève comme un chien plutôt que de

hâter d’une seconde ma phrase qui n’est pas mûre” (1852).

Winock's book will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

March 8, 2013

Sam-think for the weekend

Barry McGovern in Watt at the Barbican

By THEA LENARDUZZI

A man walks on stage in a greyish trench coat, tied at the waist, with a

grubby-looking block hat. He is carrying two intriguingly small leather cases – just room enough for, say, a week’s worth of socks and underwear and, at a

push, a change of shirt. This is Sam who, though he does not make an entrance

in Beckett’s novel Watt until the

third section of the narrative, takes centre stage in Barry McGovern’s stage

distillation, part of the Barbican’s Dancing around Duchamp season.

Sam is now Part One. There is only one. He is the One. This is

a monologue. Having shed his outerwear to reveal an old-fashioned butler’s

uniform, Sam thinks back to Watt and of how Watt came to be in the house of their

Master, Mr Knott. And of how Watt moved within the establishment once he was

there, and then of how he came to depart from the Knott place.

Watt is curious, about the house and the order of people and things, but

not too much. When he first arrives (for we find ourselves, as Sam goes through

the motions, transported back to the present tense, in a sense), he sits and watches the

embers in the grate. Sam/Watt narrates: “Watt saw in the grate, of the range,

the ashes grey. But they turned pale red, when he covered the lamp, with his

hat . . . . So Watt busied himself a little while, covering the lamp, less and less,

more and more, with his hat, watching the ashes greyen, redden, greyen, redden,

in the grate, of the range.”

One of the strengths of McGovern’s performance is that, in hearing the

text spoken aloud, its poetry is revived, and it resonates. As does the humour.

Watching McGovern is like watching Tommy Cooper – he might as well have smoothed

down his suit and asked “do you like my tails?”, before proffering two scraps of

animal hide. But, with the trench, hat and cases arranged on a hat-stand in the

half-light up stage, this is more like the Morecambe and Wise show – with a

brief moment of Fred Astaire, when demonstrating Watt’s peculiar “way of

advancing” (pictured above).

More comes of this exercise (and Beckett himself

referred to his novel as such) than one might otherwise wish of an hour in the

dark with a stranger. At any one point someone in the audience is tittering,

snorting or all-out laughing; you could call it a laugh-a-minute performance

which, for a fifty-minute monologue, is no small achievement.

But it’s not all absurd name-games. By bringing Sam to the fore,

McGovern focuses our attention on Sam, and on Sam’s think(ing). Sam’s think –

let’s call it “Sam-think”, with the same local pronunciation that, our narrator

explains, turns “third or fourth” to “turd or fart” – is, of course (of

course!) the opposite to no-think. Which is, well, who knows Watt. But Sam-think

comes of Watt and his journey to, and through, the house.

“Personally, of course”, Sam

explains, “I regret everything. Not a word, not a deed, not a thought, not a

need, not a grief, not a joy, not a girl, not a boy, not a doubt, not a trust,

not a scorn, not a lust, not a hope, not a fear, not a smile, not a tear, not a

name, not a face, no time, no place, that I do not regret, exceedingly. An

ordure, from beginning to end . . . ”. He goes on: “And the poor old lousy old earth,

my earth and my father’s and my mother’s”, culminating in – and at this point

I’m sure I heard someone stamping a foot with glee – “and fathers’ fathers’

mothers and mothers’ mothers’ fathers’ and fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ and

mothers’ mothers’ mothers’.”

There is more, too, than this frenzied, almost hypnotic, repetition of

words and passages. On Sam's/Watt’s arrival at the station, having departed

Knott’s house, he asks for a ticket “to the end of the line”. “Which end”,

comes the response, “the round end or the square end?” (there is something in this for

scholars of Woolfian temporal perception – the cyclical rhythm, the repetition – perhaps. What?). “The further end”, comes Watt’s solemn answer.

No wonder Sam regrets it all. The cases he carries are heavy with Watt, with

the memory of Watt, and what had happened (although “nothing had happened, with

all the clarity and solidity of something”), and his – their – search for

meaning. “No symbols where none

intended” – the novel’s final line – but that’s an awful lot to carry around

with you, isn’t it?

Watt runs until March 16. The Barbican's Dancing around Duchamp season will be reviewed in a future edition of the TLS.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers