Peter Stothard's Blog, page 63

April 17, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

NB In addition to the pieces linked below, we've also put this week's TLS diary column, NB, online, for a change . . . .

*

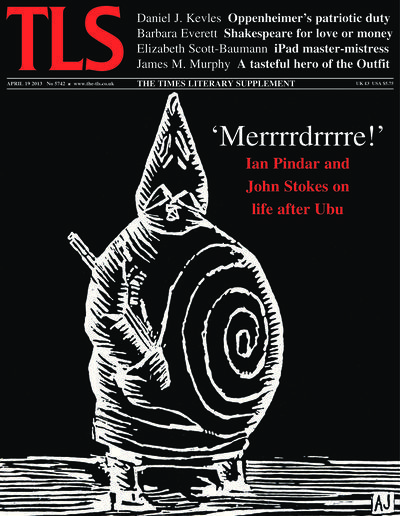

Having led the team that designed the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, J. Robert Oppenheimer emerged as the leading scientific sage of the post-war era, advising statesmen on atomic energy and urging restraint in the nuclear arms race. In 1953, though, an official inquiry concluded he was a security risk, a decision that “broke his spirit”. Daniel J. Kevles reviews a biography by Ray Monk which throws light on Oppenheimer’s beginnings as a wunderkind of physics, early left-wing sympathies, “deeply felt and lifelong patriotism” and the sense of duty he derived from his absorption in Hinduism. “After us the Savage God” was W. B. Yeats’s famous verdict after the stage premiere of Ubu Roi by Alfred Jarry, in 1896. The monstrous Père Ubu has for more than a century embodied all that is most grotesque in our social and political arrangements – yet he began life as a schoolboy joke at the expense of a physics teacher. Ian Pindar, reviewing a Life of Jarry, defies anyone to close the book “without a sense of sadness that somebody so rare and unworldly came to such a sorry end”; while John Stokes goes to see a new production of Ubu which manages, even now, to confront the audience with an upsetting image of itself – and ends by calling for bankers’ blood.

Bankers might not feature in The Merry Wives of Windsor but money, the possession of it, the lack of it, and how to come by it (by marrying it, for example) are very much to the point in this play, an odder and harsher work “than might be expected from a happy, sane, simple little comedy”, in Barbara Everett’s view. The citizens of Tudor Stratford, she writes in Commentary, would have recognized their own “tough good sense and rare eye for the main chance” in their Windsor counterparts. Raphael Lyne on The Tempest and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann on the Sonnets appear alongside her, to mark Shakespeare’s birthday next week.

Alan Jenkins

April 16, 2013

List culture

First of all, congratulations to the 20 novelists who made it on to the Granta Best of British list. All are impressive young (and youngish) writers, and all will rightly be delighted to have made the cut.

Many will already be familiar to TLS readers, and you can read our reviews of them by clicking on the links in this paragraph. Zadie Smith, Benjamin Markovits and Adam Thirlwell are seasoned authors, and the fact that they still qualify is a testament to how young they were when they first started. Others, such as Ned Beauman and Helen Oyeyemi, remain so young that they will still qualify for the follow-up list in a decade's time. Some, such as Taiye Selasi, have just hit the limelight with their debut novel (Selasi’s Ghana Must Go is reviewed in this week’s edition, out on Friday). The list includes a range of voices, from Evie Wyld to Ross Raisin, Naomi Alderman to Joanna Kavenna to Adam Foulds. Many will be rightly disappointed not to have been selected. There was no space in the top twenty for Jon McGregor, Sam Byers, Gwendoline Riley, and many others. Such is the nature of lists.

Last night’s event was well publicized and hugely well attended – so well attended, in fact, that many invitees were not able to get in and had to wait downstairs while the list was announced in the function room above. There was an air of excitement as the crush of bodies awaited the result. All good fun, of course, but the event did get me thinking about our current obsession with ranking (as opposed to critiquing) culture, and the way in which we all – journalists more than anybody – get caught up in the hype.

Perhaps the one thing more rampant than Prize Culture – what the TLS diarist J. C. wryly refers to as the All Must Have Prizes Prize – is List Culture, an even more arbitrary and compulsive phenomenon. The internet has a lot to answer for on this front. Ask bloggers what gets people clicking, and a Top Ten list will be high (number one?) on their, well, list. It doesn't matter what it's a top ten list of. Detective films. Theme parks. Chocolate bars. We all like a list. It's quick. It’s fun. And it encourages debate on comment boards.

Granta have, of course, themselves branched out. The first Best of Young American Novelists arrived in 1996. There was the inaugural Best of Young Brazilian Novelists late last year, while the format changed slightly for Granta's Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists, which featured twenty-two authors under the age of thirty-five. This should not to be confused with the Hay Festival Bogotá's initiative, which listed the "39 most promising Latin American writers under the age of 39". Incidentally, those of us who had already heard of Taiye Selasi might have done so because her debut novel appeared on Waterstone's list of 11 best first novels of 2013.

Is there any point to all of this? Well the Best of brouhaha is certainly good for Granta. As Bill Buford explained in a recent Guardian piece, the original Best of British issue was "dreamed up by a marketing guy". And a very clever marketing guy he was too. When it was published in 1983, the inaugural Best of British edition it was a novelty, generating a buzz in an era when Prize Culture meant the Nobel and Booker, and lists were something you used for shopping. Now we order our shopping online while obsessively ranking every area of culture we can think of.

Around 15 years ago, while the internet was still in its infancy, broadcasters also took advantage of the burgeoning List Culture to devise a new genre: the List Show. It was, they quickly recognized, an excellent way of recycling old material, making cheap TV and holding the attention of viewers, who sat transfixed, patiently counting down to see what had been chosen as Number One. In the UK, Channel 4 became pioneers of the genre, responsible for such classics as The 100 Greatest Films, The 100 Greatest Scary Moments and The 50 Greatest Wedding Shockers.

Is all this a problem? Not, I would argue, in as much as it's an enjoyable diversion and opportunity for debate. But I'd hate to see it overshadow the serious business of cultural criticism; that is, the serious business of reading, listening and seeing. There is, after all, a big difference between interrogating the merits and matter of a given piece of art and putting it in an Excel spreadsheet.

And here's the real issue. Criticism can be maddeningly slippery. It seeks to probe and unravel, rather than order and rank. It can be provocative and playful and, at times, opaque. Its value judgements are allusive, elusive and adjectival, rather than numerical. It takes time. It doesn't always generate headlines. It is, above all, difficult to confine to a list.

April 10, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

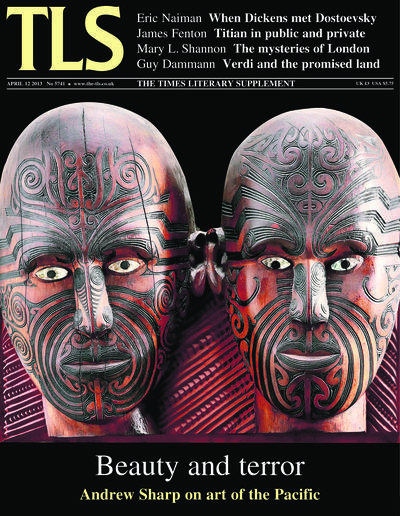

According to the art historian Francis Haskell, Titian was one of three artists who “for no extended period since their lifetimes” had not been considered great painters. (The others were Raphael and Rubens.) The high regard has been constant; but “what people have meant by Titian, what they perceived his high qualities to be – that”, James Fenton writes, “is still a question worth asking”. Biography can help to answer it, and it is all the more surprising that Sheila Hale’s should be the first full Life since 1877 – “it makes one wonder what other more pressing tasks (in the art history world) were in hand”, muses Fenton, who salutes a work that portrays Titian as both “the quintessential court artist” and “a beady-eyed old timber merchant”. Questions as to “whether ‘art’ and ‘art history’ are European concepts better not employed outside their region of origin” are “finessed” by the editors of Art in Oceania, but Andrew Sharp is in no doubt about the rich aesthetic and historical meanings of the works it records – best approached through the book’s “well-chosen and sometimes stunning” illustrations. Illustrations – 1,700 of them, “in all the glory of digital polychrome” – reveal the secrets of London’s hidden interiors, in a book J. Mordaunt Crook finds “electrifying”; while Allan Massie enjoys the poet Robert Crawford’s study of two ancient rivals, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Ten years ago, an article in the journal of the Dickens Fellowship included a passage from one of Dostoevsky’s letters, referring to his visit to Charles Dickens. The “meeting” gained currency in more than one subsequent biography of the English novelist, but specialists in Russian literature were not so sure. Eric Naiman was one, who decided that the article’s sources and its author, Stephanie Harvey, might bear further investigation. His researches drew him into a network of “mutually supportive” contributors to scholarly journals and online publications whose writings all appeared to point to the same raison d’être . . . . A remarkable tale of modern literary life unfolds in Commentary this week.

AJ

April 8, 2013

The Great Vituperator

By TOBY LICHTIG

Yesterday, on the BBC's

Andrew Marr Show, William Hague warned of the dangers of

"miscalculation" by the North Korean regime, "which has worked

itself up into [a] frenetic state of rhetoric". The concern, said the

Foreign Secretary, was that Pyongyang would start to believe its "own

paranoid rhetoric".

The

North Korean government is, of course, notorious for its bellicosity; but it has in

recent weeks taken the idiom of diplomatic insult to new heights. These threats

and affronts are frequently quoted in the media, but for those interested in

exploring at closer quarters the lexicon of aggression and oppression embraced

by this most Orwellian of states, it is worth paying a visit to the website of the

Korean Central News Agency (available in English- and Spanish-language

translation), which collates announcements from The Party, official statements from North

Korea's political leaders, and editorials and reports from outlets such as the state newspaper, Rodong Sinmun.

Known

to some journalists as "The Great Vituperator" (see Barbara Demnick's excellent book about the country, Nothing To Envy, 2010), the KCNA is a

treasure trove of linguistic abuse, throbbing with language of such eccentric crudeness

and outlandish bombast that it would be entertaining were it not so disturbing.

In recent days, the "US

imperialists" and their South Korean "puppet traitors" have been habitually derided as "mentally deranged", "impudent" and

"harassers of peace". They are accused of "sophism",

"heinous criminality" and

"letting loose a spate of balderdash". The enemies of

Pyongyang are "war maniacs" and "mad about nuclear war". The

authorities in Seoul are "a group of murderers who cannot live under the

same sky [as North Korea]", while the "imperialist rabid dog" in

Washington is "kicking up [a] frantic nuclear war racket".

Sometimes

there can be a quaintness to the English – abetted by the apparently dodgy

translation – such as in that use of "racket", or in the description

of America's "nuclear war manoeuvres" as "madcap".

At

other times, the tone is almost lyrical: South Korea is "a tundra of human

rights", its leaders "bent on a wild dream", its military

masterminds "working with bloodshot eyes" to "inflict heinous

war". These "lackeys" and "stooges" are

"cancer-like entities", "poisonous herbs" that "should

be mercilessly rooted out by arms so that they may not sprout again". The

Blue House in Seoul is "the cesspool of all evils". American military

support is "a foolish act reminding one of a drowning man catching at a

straw".

Particularly

inventive use is made of reported speech. South Korean leaders rarely "speak",

according to the KCNA: rather, they "trumpet" (propaganda; hatred;

insults; lies) or "fabricate" or "bluster".

The

KCNA is vivid in its suggestions about what to do with these "traitors".

The citizens of North Korea must "put the warmongers into the red hot

iron-pot of Hell". The United States, we are told, "will perish in

the flame kindled by it and kneel down before the army and people".

Washington will become a "sea of fire" and the enemies of Kim Jong-un

will be sent "to the bottom of the sea as they run wild like wolves

threatened with fire".

This

rhetoric is undoubtedly colourful. To what extent is it dangerous? I'll let the qualified North Korea analysts answer that one, but it may be worth

noting a recent story about a former North Korean army officer who fell foul of

Kim Jong-un. According to reports, the unfortunate individual, Kim Chol, was

sentenced to death and promptly executed not by a three-man firing squad, as is

traditional in the country, but by a mortar

round. This is to say, he was placed in a spot in a field and then bombed.

The apparent reason for this imaginative piece of brutality is that the Supreme Leader is alleged to have desired

that "no trace" of the man be left behind, "down to his

hair".

Whether

or not this story is true – and given the historic excesses of the regime, it may be plausible – it's a salient reminder of the powerful effect that

words can have, particularly when uttered from on high. Remember that legend

about Henry II and Thomas à Becket? Much has been said in thoughtful commentaries

not of Kim Jong-un's actual desire for a doubtless suicidal conflict, but of someone

making a "mistake" amid the sabre rattling, pushing an ill-chosen

word into a hostile deed, and setting in motion a disastrous chain of

escalation. We can only hope that even members of Kim Jong-un's inner circle

take the rhetoric of "The Great Vituperator" with a hefty dose of salt.

April 5, 2013

Great (and graphic) Keats

By MICHAEL CAINES

On April 23 the Institute of Ideas hosts the first in a proposed series of literary evenings on the subject of “great books”. They’re certainly beginning with greatness: not only Keats’s poems but his letters, too, with their deep stores of delight: “I will clamber through the Clouds and exist”, for example, his way of describing to Haydon, in 1818, his plans to “see all Europe at the lower expence”; or, the following year, his demand to Fanny Brawne to ask herself “whether you are not very cruel to have so entrammelled me, so destroyed my freedom”; or, a year on again, his lament that he cannot “leave my lungs or stomach or other worse things behind me”.

The illustration above, however, comes from quite a different kind of tribute or commentary on Keats: the first in a four-part comic by P. M. Buchan and Karen Yumi Lusted inspired by "La Belle Dame Sans Merci". It has a modern setting, and comes with a “back-up essay” by Miranda Brennan on Keats and feminism, and a link to a soundtrack by Brendan Ratliff. So it’s a far cry from asking, with Jonathan Bate, “What was he really like?”, as in this TLS piece from last year, or from following Keats through his correspondence, towards the clouds.

Instead – intriguingly, and on some pages wordlessly – this graphic Belle Dame draws on Keats's poem for its power. In the middle, Buchan quotes those deadly simple lines from the fourth stanza, the first spoken by the “palely loitering” knight:

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful – a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

The first issue merely sets up the story, but I'm hoping its creators are considering a sequel – perhaps a sequel based on a sequel – i.e., on “The Enchanted Knight” by Edwin Morgan, with the rust “Flowering his armour like an autumn field”:

Lulled by La Belle Dame Sans Merci he lies

In the bare wood below the blackening hill . . . .

Edwin Morgan! Now there's a writer of great books for the Institute of Ideas.

April 4, 2013

Jacob Epstein’s party in bronze

By MICHAEL CAINES

Any time between now and November 24 would be a good time to find yourself in the vicinity of London’s National Portrait Gallery: head up to Room 33 (the high-ceilinged mezzanine before you get to the Victorians), and there you’ll meet a devil’s dozen of portrait busts by Jacob Epstein, mainly in bronze. It’s quite a party, and entry is free.

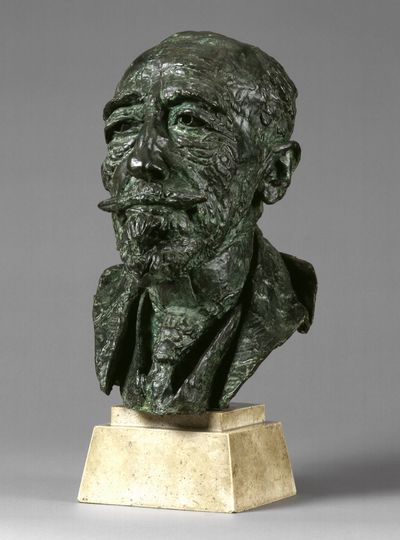

Several of the guests are literary men – T. S. Eliot, Joseph Conrad, George Bernard Shaw, W. H. Davies – among whom Conrad seems to have been most pleased with Epstein’s work, and appears to best effect. This photo doesn’t capture anything like the weird sensation of being able to look him in the eye, as it were, in 1924, the year of his death:

It only enhances the weirdness of the occasion that this wizened grandee perches in a corner with a fuller faced, uneasy Ralph Vaughan Williams on one side of him and a couple of swell large black-and-white photographs on the other. One of these images is of Gina Lollobrigida X 2 – the original is raising a gloved hand as if to ward off Epstein’s curiously unimpressive version of her. I wonder, too, what T. S. Eliot made of what Epstein made of him:

Further signs of interesting sculptor-sitter relationships appear when you turn around and find that young “spiv” (Epstein’s word) Lucian Freud next to you, or Augustus John (looking older than his years), or the NPG’s recently acquired Jawaharlal Nehru (who came by the studio out of curiosity and ended up sitting for Epstein). And at least one sitter always troubled Epstein: himself. Here he is, looking vexed by the whole business, and wearing the cap that the chilliness of his studio obliged him to wear:

Head and shoulders above them all, however, is the great actress Sybil Thorndike, over five feet above the ground, as if on a stage (and as stipulated by the sculptor). In fact, with her eyes fixed on heaven, Thorndike is here playing Saint Joan, the part Bernard Shaw wrote for her, and this further sets her apart from her neighbours; they are Epstein’s impressions of personalities as well as faces, but in this case a third party is present. Whether the third party is the actress or her role is more difficult to say.

At least it is clear what Thorndike thought of the bust: she kept it on a pedestal in her sitting room and praised it as “a perpetual stimulus and inspiration”. Shaw’s wife, by contrast, wouldn’t let him keep his in the house . . . .

Photographs © National Portrait Gallery, London

April 3, 2013

Jared Diamond’s other worlds, compulsory reading for the military, grandiose triptychs

In this week's TLS - A note from the History Editor

The layperson

used to have a pretty good idea of what anthropologists did. They were white

men (usually men) from “civilized” countries who went to “live among” a tribe

and record their ancient ways. This was the model that Margaret Mead (the

exceptional woman) promoted when she became perhaps the world’s best-known

anthropologist in the middle of the last century. Anthropologists’ discoveries

were also offered as instructions for how to improve our own ossified Western

ways of doing things, from making war to bringing up children. But this kind of

anthropology started to get a bad name, as it was realized that, in various

ways, it valued cultures differently. Anthropologists started to turn up in

coffee bars or offices more often than longhouses. Reviewing a new work by

Jared Diamond, one of the best known anthropologists since Mead, Ira Bashkow

welcomes a return to the sort of anthropology that unashamedly sees indigenous

societies as offering lessons to the West. But he also warns against the

“historical” view that such societies demonstrate “how all of our ancestors

lived” in the not too distant past, which leads Diamond down some murkier

byways.

Our reviewers’

discriminating natures tend to ensure that books are rarely greeted with

unstinting praise in our pages, so it may be worth pointing out that this week,

two new masterpieces are announced. Michael Howard reviews War from the Ground

Up by Emile Simpson, a former Gurkha officer in Afghanistan, and finds a “work

of such importance” that it should be “compulsory reading” for all levels of

the military. He concludes that the book “deserves to be seen as a coda to

Clausewitz”. In Fiction, Hal Jensen puts aside his initial scepticism about the

latest Faber Finds reissue, the work of the little-known American novelist

David Stacton, and discovers an “astoundingly good” writer. Stacton wrote

contemporary novels and pulp productions under various pseudonyms, but it was

in his three historical “triptychs” that his “melodramatic and a mite

grandiose” talents really shone through.

DH

March 30, 2013

You say Bombay, I say Mumbai . . .

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Bombay was renamed Mumbai in 1996,

largely at the instigation of Bal Thackeray, the firebrand politician who died

last year. Thackeray founded the Hindu far right Shiv Sena party, which

provoked inter-communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims both in

the city and across India. As for “Bombay”, he felt the name had too many

associations with the city’s colonial past – its replacement is said to honour

the city’s patron deity, the Goddess Mumbadevi. What, I wonder, did Thackeray

make of his own surname, one which his father adopted out of admiration for the

Victorian novelist?

The writer Suketu Mehta relates a

tense interview with Thackeray in his brilliant contemporary chronicle of his native

city, Maximum City: Bombay lost and found (2004) - what must be one of the last

books with the old name in its title. At one point Thackeray firmly corrects

Mehta’s use of the name “Bombay”.

Mehta points out that if the fourth

largest city in the world in terms of population “were a country by

itself in 2004, it would rank fifty-four”. On reflection it’s extraordinary

that this megalopolis of 20 million plus should have changed its name so easily – was

there any protest? I don’t remember now. Admittedly the old name is clearly

recognizable in the new one. But nevertheless can you imagine Boris Johnson as

mayor of London deciding to rename the city Londinium? Think of the

administrative upheaval.

But as Mehta wrote ten years ago:

“name-changing is in vogue in all of India nowadays: Madras has been renamed

Chennai, Calcutta, that British-made city, changed its name to

Kolkata”. Bangalore has since become Bengaluru (but will that one ever

properly catch on, with its unnecessary extra syllable?). I loved the

name Madras, but I appreciate these decisions aren’t made with my

aesthetic preferences in mind. And there’s something to be said for a proper

name change like Madras to Chennai, a clean break. As for Mumbai, it doesn’t

trip off the tongue as easily (for me at least) as Bombay, but it’s official and one should

respect that - I don't live there after all.

Penguin India seem

to view it differently. I had an email exchange with a TLS contributor recently over his

use of “Bombay” in a review – I suggested changing it to Mumbai but he pointed

out that the author of the book in question opted for

Bombay, with the clear blessing of his publishers Penguin. You say Bombay, I say Mumbai

. . . .

I think of another megacity and how

it has got its naming so right: New York,

whose names add up to one big

topographical prose poem - this is hardly an original observation I’m sure:

Upper West Side, Upper East Side, Lower East Side, Morningside Heights, Columbus

Circle, Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, F.D.R. Drive, Staten Island - the list goes

on.

Martin Amis for one saw the music in these names. Think of this riff on John

Self’s travails in Money: “My head is a city, and various pains have now taken

up residence in various parts of my face. A gum-and-bone ache has launched a

cooperative on my upper west side. Across the park, neuralgia has rented a

duplex in my fashionable east seventies. Downtown, my chin throbs with lofts of

jaw-loss. As for my brain, it’s Harlem up there, expanding in the summer

fires”.

Which brings me to the thought: can place

names be ranked aesthetically? I think they can and I’ve compiled a list of twenty

that particularly appeal to me. I’ve excluded country names, and written out of

contention names that flaunt their beauty, such as Belo Horizonte, Saratoga

Springs, Alice Springs, Pacific Palisades, Tierra del Fuego, Martha’s Vineyard,

Grimsby . . . .

It’s a very subjective thing of

course, and I’m probably revealing a tin ear here (I haven’t tried them out on

anybody). I particularly like names that are hybrids, such as Cox’s Bazar, in

Bangladesh - or ones that end in “ville” - excluding the deeply unimaginative

Townsville in Australia.

Here they are, in no particular order

– I could easily come up with 20 more and call them my favourites too, and 20

more after that: Devizes in Wiltshire, for example, or Galashiels. I kick off

with Jacksonville, although it was a close-run thing between it and Galveston,

both having that rather beautiful stress on the first syllable.

Jacksonville

New Orleans (wherever the stress

falls)

San

Francisco

Valparaíso

Asunción

La Paz

Brazzaville

Kinshasa

Khartoum

Cairo

Jeddah

Isfahan (and Suza)

Cox’s Bazar

Shanghai

Adelaide

Istanbul

Sarajevo

Nuremberg

Syracuse

Vladivostok (of course)

Other suggestions

gratefully received.

March 28, 2013

Javier Marías, part two: Digressions

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Digressions in the fiction of Javier Marías (see yesterday’s

post) can be extensive. “My intention is not that I irritate the reader”, Marías

told James Runcie at the Southbank last week. “The digression can be as interesting [as

the action that preceded it]. I compare it to . . . the second part of The Godfather – there are the two different times.

Al Pacino in the present and Robert De Niro in the past, in Sicily . . . . When

the film jumps you’re annoyed. But Sicily is also so interesting that when it

goes back to the present you say ‘oh’ . . .". Marías went on to mention Don Quixote ("[They’re] about to hit each other with a sword and Cervantes stops the action.

He never comes back to it . . . . That’s even more irritating than I may have

been") and Laurence Sterne ("Tristram Shandy interrupted as many

times as he wanted") – and suggested that such narrative quirks are

justified partly by how our brains work. “Minutes have a different duration in

our memories.”

Asked

why his sentences were so long, Marías borrowed a reply from William Faulkner:

“Because I’m not sure I’ll be alive for the next one”. Runcie observed that

they contribute to Marías’s “authority of rhythm”. The fact that this rhythm

appears to the reader to remain unbroken strikes Marías as “miraculous”, given his

writing process; he writes, as he puts it, not with a map, but with a compass

(“If I knew the whole story in advance I wouldn’t write it. I’d be bored”), and

he usually writes a page a day, but there are days – sometimes long stretches –

when he doesn’t have time to write at all. He told us that he was careful, when returning after

a break, not to read too many pages back to himself – “What if you don’t like

them?” – and referred to Jorge Luis Borges’s idea that a “definitive” text can

result from only two things: religion and exhaustion. (“Why should draft 12 be

more definitive than 11? . . . . And there’s always 13.”)

When

Runcie praised Marías’s forensic analysis of infatuation – “an accurate

portrayal of traumatic love” – Marías explained that the Spanish "Los

enamoramientos" has no perfect equivalent in English. “Infatuation” is

acceptable, he said, but it has a negative nuance that the Spanish doesn't have; the

Spanish is more simply “the process and the state of being in love”. As a title

it therefore gives less away. Being in love is something that has a rather

good reputation, said Marías. “Many think that it makes us better, more noble

. . . . It is also true that it may be the other way round . . . . I have seen

noble people act vilely.”

In

the question-and-answer session Marías said that he didn't read much literary

criticism, apart from reviews, but that a few books – including Mimesis

by Erich Auerbach (reviewed in the TLS by George Steiner in 2003) – had been very important to him; and that The Infatuations was perhaps his most pessimistic book, reflecting his belief that people, in

his own society at least, are more and more reluctant to take responsibility,

increasingly indifferent to crime and prone to blaming their situation – the

emotional legacy of their childhoods, or the state of being in love – for their

misdemeanours.

Marías

didn’t forget to acknowledge the translator of his work, Margaret Jull Costa

(mentioned by Adrian Tahourdin in his round-up of the 2012 translation prizes):

“I have been very lucky . . . . She is very faithful. She finds very good

solutions . . . . The quality of the doubts and questions [she has] tell me

how good she is”. “I even think sometimes that my novels read better in

English.”

March 27, 2013

Javier Marías on secrecy and reflection

By CATHARINE MORRIS

In

his recent review of the The Infatuations, Javier

Marías’s metaphysical murder mystery, Adam Thirlwell described Marías’s prose

as “sensual and philosophical, simultaneously . . . . His narrators can

drift for giant lengths, and yet still re-emerge, calmly, on to the same stage,

transformed by their reflections”. He went on to say that Marías’s

“acrobatics between paragraphs or chapters can only be coarsely

paraphrased”. So it was with interest that we gathered to hear Marías interviewed by James Runcie at the Southbank last week.

What would he say about his own acrobatics?

The

first thing he revealed was that he began The Infatuations with only a

vague premiss: he was interested in the idea of a woman who would stay with a

man who had caused her great harm. Doing so might be a strange kind of justice,

a compensation, he said; she might wordlessly be saying: “you must make up for

this by being by my side for ever . . . and my very presence will remind you

all the time of what you have done”.

His

next step was to consider what the man’s crime might have been. Then he

recalled something a friend had told him – for years she had observed a

particular couple in a café every day. But one day the couple stopped coming;

the man had been killed. The Infatuations duly begins: “The last time I

saw Miguel Desvern or Deverne was also the last time that his wife, Luisa, saw

him, which seemed strange, perhaps unfair, given that she was his wife, while

I, on the other hand, was a person he had never met . . .”. The “absolute

fiction” starts 25 or 30 pages in, depending on whether you are reading in

English or Spanish.

Like

much of Marías’s fiction (and a speech he wrote for the Spanish Academy),

The Infatuations addresses the impossibility of knowing anything or

anyone with absolute certainty. Narrating is something we do all the time, said

Marías; someone says “How are you?” and you reply – perhaps with an account of

your journey to work. “But even that small thing is very difficult to tell . .

. . You had one point of view; others had a different one . . . . It even

happens with history. It’s almost impossible to tell these things with

accuracy. [But] fiction does that.”

If

he had to say what The Infatuations was about, he’d say that it was about

secrecy and the convenience of secrecy, how "civilized" secrets can be. He

recalled a line from his novel A Heart So White (1992): “ears don’t have

lids that can close against the words”. “If you told me that you had killed a

woman in the park last night, I’d probably wish you hadn’t told me . . . . I

might think ‘James seems like a nice man. I don’t want him in prison, not

immediately at least' . . . .”

Moving

swiftly on, Runcie observed that the narrative of The Infatuations was

full of reflection – he referred to a passage in which a single conversation is

revisited again and again. “There are all kinds of novelists”, said Marías.

“Some perceive what is normally almost imperceptible and see the meaning in it

. . . . Say you spend the whole evening arguing with somebody . . . . It is very

likely that what remains in your memory is a small detail, a gesture or a look.

That’s what the novels pick up.”

Marías’s

narrators tend also to make a lot of literary references – to Balzac, Dumas and

Shakespeare, for example – but it is not in a metaliterary way, said Marías;

it’s “more in the way we all do it: ‘I’ve seen this film and I talk about it' .

. . ”. So the sequence in The Infatuations in which the narrator’s

lover relays the plot of Balzac’s novella Colonel Chabert – in which a

man mistakenly buried after the Battle of Eylau returns to Paris years later to

pick up where he left off – was not included for the sake of it; the story is

something you might dwell on naturally: “My own father died seven years ago”,

said Marías. “[Say] the dead came back five or seven years later . . . . We

inherited some money. Probably we’ve spent it by now . . . . And what about the

house? . . . It could really be a great misfortune if they came back . . . ”.

More on Marías’s interview to come tomorrow . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers