Peter Stothard's Blog, page 59

June 18, 2013

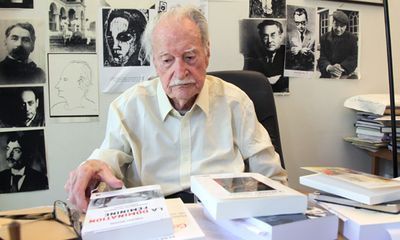

The careers of Maurice Nadeau

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Maurice Nadeau, who has died at the tender age of

102, was, according to John Calder, writing in the TLS, “the most versatile

and many-faceted figure in post-war literary Paris”. Nadeau cut his teeth on the books pages of Combat,

before becoming its director. Albert

Camus was an early editor. Among Nadeau's books were a history of Surrealism (1945),. He later fell out with the high priest of that movement André Breton. There were also books on Sade

and Flaubert. Nadeau had a lilelong commitment to the Left and was involved in anti-Algerian war demonstrations.

In 1966 Nadeau set up the Quinzaine littéraire, taking the

recently founded New York Review of Books

as a model (although, unlike its precursor, it generally eschewed polemics). His assistant on the journal

was Anne Sarraute, daughter of the novelist Nathalie (who herself died at the

age of ninety-nine). According to Marion Van Renterghem, writing in Le Monde (June 18), when Anne Sarraute

died in 2008, Nadeau exclaimed “Subir ça à 97 ans, mince! J’en ai pris un vieux

coup” (a real blow). The Quinzaine,

which has always given generous coverage to foreign literature, preserves an

old-fashioned appearance and doesn’t pay its contributors; it has struggled in

recent years against a falling circulation, but Nadeau was determined to keep

the show on the road. It limps on to this day, and was recently bailed out by the luxury goods maker Louis Vuitton.

The biographer and critic Pierre Assouline, writing

on his blog La République des

livres, listed well over a hundred authors French readers can thank Nadeau

for having discovered in his role of publisher. They include Georges Perec (Les Choses), Roland Barthes, Michel Leiris, Tahar Ben Jelloun,

Jean-Marie Le Clézio and, among foreign writers, Lawrence Durrell, Malcolm

Lowry, Jorge Luis Borges, Richard Wright, J. M. Coetzee, Thomas Bernhard and

Leonardo Sciascia. He hailed Claude Simon when his first novel was published,

defended Henry Miller against the censors and just missed out on publishing Samuel

Beckett. He had no proprietorial feelings towards writers and was happy to let

them move on to bigger publishers - Nadeau claims never to have made any money

for the various publishers he worked for: “just ask them!”

More recently Nadeau published Michel Houellebecq’s

first novel Extension du domaine de la

lutte (1994). Houellebecq went to the giants Flammarion for his second and

subsequent novels. Nadeau, meanwhile, turned down Houellebecq’s poetry, explaining that

“Houellebecq has published a poem called '[Jacques] Prévert est un con’ and as this ‘con’

is my friend . . .”.

June 17, 2013

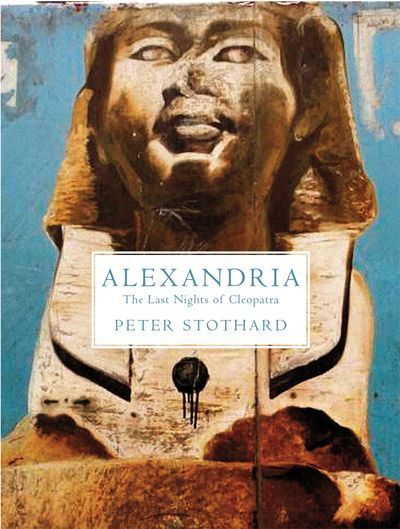

Radio 4 Book of the Week - and other Alexandrias

I had to park by the side of the road to hear Kenneth Cranham read Part One of my Alexandria;The Last Nights of Cleopatra this morning.

It was a peculiar physical experience to hear a diary written two-and-a-half years ago in Egypt, about fifty years ago in Essex, by a Wapping pub on the banks of the Thames.

But it was safer than driving.

Other versions have appeared in The Spectator, The Scotsman, The Times, The Mail on Sunday, The Glasgow Herald, the Literary Review and the elegantly titled Mirabile Dictu which comes from Iowa.

Part Two of the BBC adapatation, by the scrupulous producer and adaptor, Jill Waters, is at 9.45 am tomorrow.

Related articles

Alexandria: speech and Spectator

Alexandria: speech and Spectator Taste the Mermaids

Taste the Mermaids

June 14, 2013

Books that go bump in the night

By MICHAEL CAINES

Apparently it's still just about possible – today at least – to book for the A. N. L. Munby conference at the end of this month that I mentioned previously on this blog. I mention it again not only in a spirit of rampant self-promotion (I'm giving a paper on Munby and the TLS – of all the unexpected things) but also to note something I only mentioned in passing last time round: that Munby the bookman was also Munby the writer of ghost stories.

The Sundial Press, more familiar to me as the small press that has reissued some works of the Powys brothers and their circle, are reissuing a collection of these stories, The Alabaster Hand. The claim, drawn from the Who's Who in Horror and Fantasy Fiction, is that Munby is the writer "who comes closest to inheriting the mantle of M. R. James".

That's quite a claim, isn't it? Other readers must have their own candidates to inherit the mantle of the master, but here at least are a few votes in Munby's favour. It's also a bold statement given how difficult it is, apparently, to write a ghost story that can actually scare its readers. And it might involve avoiding Jamesian trappings as much as paying homage to his techniques.

To take a personal favourite as an example: there's a purportedly real-life incident buried in Twenty-Five, an early exercise in autobiography by Beverley Nichols, and it's all the better for being surrounded by Nichols's otherwise unflappable reminiscences about mixing with politicians, writers, etc. It is the last place you'd look for a ghost story.

In any case, I'm sure Munby, as a book collector, would have been amused, if not proud, to see "near fine" copies of the first edition of his collection going for somewhat more than a song.

A short TLS review of the reissue will follow in due course, I hope. For the time being I'm looking forward to the postprandial entertainment for delegates on the first night of the Cambridge conference: a reading from one of those stories with an appopriately bookish inflection, "The Tregannet Book of Hours", by the actor Richard Heffer.

June 13, 2013

Authors’ nous – Eliot, Dickens and Sterne

By MICHAEL CAINES

Not all authors have nous – meaning practical intelligence, to extend one OED definition of the word – when it comes to the business of selling books. But see above for a heartening example of George Eliot’s mind at work on this noble subject. Here, on May 2, 1873, “M. E. Evans" announces herself to be “nothing but content” with her publisher's proposal to reduce the price of her books from 3/6 to 2/6, and ditch some of the embellishments:

“To my taste the volumes will be better for being freed from the illustrations – save & except the pretty vignettes. . . . The appearance of the 3/6 volumes is so handsome that they may part with some of their costliness & yet be respectable.”

Eliot saw how such a simple expedient could benefit both parties:

“As to the effect on future sales I imagine that the wide distribution of Miss Austen’s books in the shilling copies greatly increased the sale of the Bentley’s Library Edition. The Parlour Library made her name. . . . Let us hope that the 2/6 edition of the five books would cause all the better sale for a future revised series including all my works – prose and verse.”

And so nous based on precedent (“the wide distribution of Miss Austen’s books”) joins hands with authorial tenderness for her own creations (“a future revised series” that tenderness eventually produced, a few years later, was the grand Cabinet Edition of Eliot’s works – twenty beautiful volumes – not exactly bestsellers, though. The cut-price Eliot, by contrast, points the way to the mass paperback schemes of the twentieth century.

The letter isn't in the standard edition of Eliot’s letters, and is currently itself on sale, for £3,000, courtesy of the nineteenth-century specialists Jarndyce, alongside other wonders I hope to gawp at during the London International Antiquarian Book Fair, which opens today. Jarndyce also have, for example, various Dickens ALSs, exhibiting nous, or at least an informed cynicism, as he seeks to prevent the unauthorized performance of a play by him and Wilkie Collins: “I privately doubt the strength of our position in the Court of Chancery, if we try it; but it is worth trying”.

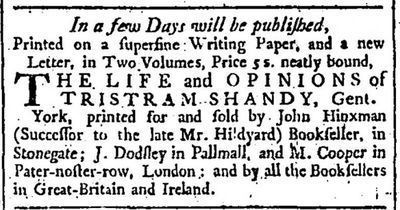

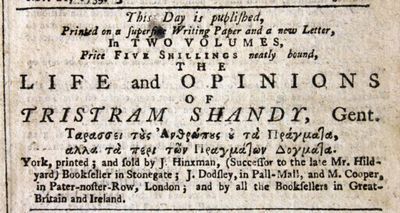

Compare these wise authors of the nineteenth century with a recently discovered oddity concerning one of the greats of a hundred years earlier, Laurence Sterne.

The first volumes of Sterne’s ab ovo masterpiece, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, appeared in 1759. When exactly it was published that year has remained something of a mystery.

This much has been known for a while, courtesy of an advertisement spotted in the London Chronicle on December 20:

Which sent the investigators looking for a publication date around Christmas. Alas, that was the wrong way; and Elinor Camille-Wood and Patrick Wildgust have earned the admiration and gratitude of biographers, literary historians, pedants and obsessives the world over for turning in the other direction, and finding this ad buried in the York Courant for December 18:

This is good timing, as the tercenternary of Sterne’s birth falls this year. Does it have anything to do with authors’ nous? Well, maybe. Note that devilish Greek couplet in the middle of the York ad – it’s taken from Sterne’s title page:

You might wonder who thought it was a good idea to reproduce a motto from Epictetus (“Not things, but opinions about things, trouble men”), given that, as W. G. Day notes, “It is most unusual for Greek type to be used in an advertisement for a work of fiction in this way”. Was this Sterne himself “aiming his work at an audience of higher than average intelligence and linguistic competence”? And, showing another kind of nous, was it wiser of the London booksellers to take a more “pragmatic view of the market” and omit “what might have been seen as off-putting to many possible readers”?

“The Book will sell”, Sterne had assured them, earlier that year. A common conviction among his sort . . . .

Photo credits: George Eliot letter courtesy of Jarndyce; Tristram Shandy images courtesy of the Laurence Sterne Trust.

June 12, 2013

All for one and one for all

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

"It’s 1–1 mate.” Those were the words the England

all-rounder Andrew Flintoff apparently uttered to the Australian fast bowler Brett

Lee immediately after England had won the second Test at Edgbaston in August

2005, in what has become an iconic image of sportsmanship (above). Australia

had blown England away in the first Test at Lords and many of us feared the

prospect of a horribly one-sided series, with the greatest Test team of the

modern era effortlessly demonstrating its vast superiority once again.

That’s not how it turned out of course. At the end

of five acts of nerve-shredding drama England emerged victorious, just. The 2–1 margin doesn’t begin to suggest how close the series was. As Flintoff reminded

listeners to BBC Radio Five Live last week in the wonderfully entertaining

first 90-minute instalment of an Ashes retrospective, if the spearhead of the

Australian bowling attack Glenn McGrath hadn’t injured himself by accidentally

treading on a cricket ball just before the start of the second Test (and

thereby missing two matches), Australia would probably have won. Luck played a

big part in England’s triumph.

For the programme the Lancastrian Flintoff brought

together the three other members of England’s fast bowling attack: Stephen

Harmison, Matthew Hoggard and Simon Jones. Harmison the gangling and

occasionally lethal giant from Durham, Hoggard the bluff Yorkshireman and

workhorse, and Jones the Welsh pin-up with a devastating line in reverse swing.

Like a gang of gunslingers reliving their finest hour, the quartet were quick

to pay tribute to each other’s achievements, to praise the nerveless captaincy

of the remarkable Michael Vaughan, and to give credit to the fifth member of

the bowling attack, the dependable (and occasionally brilliant) off-spinner

Ashley Giles (affectionately known as the “King of Spain”). Together they

managed to get the better of one of the most illustrious batting line-ups in

history, the great Adam Gilchrist’s vulnerability to Flintoff’s aggression a

particularly notable success.

It was almost moving to hear how much genuine

pleasure they seemed to take at the time in each other’s success: cricket is a

team game in which individual achievement counts for everything, but here was a

case of “all for one and one for all”: when Simon Jones broke down halfway

through the fourth Test at Trent Bridge he felt he had let his fellow bowlers

down; they, on the other hand, were mortified that he wasn’t able to share in ultimate victory. As

it turned out, the injury was so serious that Jones had just played his last

Test, an international career largely unfulfilled.

But what a summer the quartet had: Flintoff touched

cricketing greatness as a bowler and batsman for those intense six weeks,

Harmison was frequently hostile, Hoggard belied his workhorse reputation by

regularly making inroads into Australia’s top order and Jones was, on his day,

simply unplayable. In a low-scoring series, only three Australian batsmen made

a century (England managed five). Shane Warne was of course immense, but even he

couldn’t carry the Australians to victory on his own.

It seemed, by the end of the summer, as though

Vaughan’s team were on the brink of cricketing greatness. Sadly, injuries took

their toll, not least with Vaughan himself. Flintoff never reached those heights again, while Harmison’s

fragile confidence was ruthlessly exposed by the Australians in their home

series 18 months later – a shocker which they won 5-0. Hoggard was unceremoniously

dropped. Sporting careers, it seems, are, like political careers, too often

destined to end in failure (remember how the great Ian Botham limped on for

five years after he should have retired from international cricket?).

In a second instalment this week Flintoff revealed a

surprising admiration and affection for the Yorkshire colossus Geoffrey Boycott –

a rare Red and White Rose mutual admiration society (Flintoff’s public spats

with his fellow Lancastrian Michael Atherton, on the other hand, have been

rather unseemly). The two could not have had more contrasting approaches to the

game, Flintoff barn-storming to the point of recklessness and Boycott (below – what a long bat he seems to be wielding!) self-absorbed to the occasional detriment of the team, but utterly dedicated; it was fascinating

to hear such appreciation of each other’s approach.

All this is part of the build-up to this summer’s

Ashes series, which opens on July 10. England are favourites, a position they

are not always comfortable with. Just one small footnote: the Australian selectors

have omitted Mitchell Johnson, their mercurial “once in a generation” bowler.

This is baffling as, by my reckoning, in two Ashes series Johnson has almost singlehandedly won two

Tests with his bowling. Will they come to regret it?

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Editor

Victor Serge was for Susan Sontag one of the most compelling of twentieth-century heroes. He was a Russian writer and activist who, as Rachel Polonsky writes this week, exemplified the virtue of “the political intellectual without property or nationality, cleansed of the stain of revolutionary violence by his own marginality and failure and the eloquence of his conscience”. Some of that eloquence can be seen in his memoirs, written in Mexican exile in 1941, published now in their most unexpurgated form. Polonsky notes how Serge’s novels, “with their various (self)-portraits of nobly troubled men of action” are drawn from “the cinematic atmosphere and political pathos” shown in his recollections of revolution itself.

John Cornwell and George Bornstein consider two wartime leaders who could not (or chose not to) be so clear cut in their positions. Cornwell reviews new books on Pius XII, the Pope who steered a nervous course between Allies and Axis, a balancing act that has since inspired fierce critics as well as fervent admirers. “For those who have no vested interest on either side”, he notes, there are now “two reliable, complementary studies” of one of the twentieth century’s most enigmatic figures. Bornstein reviews FDR and the Jews, a sympathetic study of Roosevelt and his predicament over the protection of European Jewry in an age of “widespread anti-Jewish feeling”. The authors’ sympathy, he argues, sometimes skews their judgement, particularly towards anti-Semitic remarks used as “an ice-breaker” in conversations with Ibn Saud and Stalin.

Peter Rutland calls the break-up of the Soviet oil industry one of the twentieth century’s greatest dramas, a play that has created more than a hundred billionaires in a country where twenty-five years ago it was criminal speculation to sell jeans in the street. He praises Thane Gustafson for writing the “definitive work” on a world of virtuous capitalists and violent crooks, even if sometimes, perhaps, saying rather less than he knows.

Peter Stothard

To view this issue’s Contents Page, click here.

June 11, 2013

The Moo Man is coming . . . .

By Thea Lenarduzzi

The world is

divided into those who have milk in their coffee and those who take it black.

For Louis Untermeyer in his poem of 1915 “Gilbert K. Chesterton Rises to the

Toast of Coffee”, it distinguishes the sort of “men who will never be drunk” from

the rest:

“So, gentlemen, up with the festive cup, where Mocha and Java unite;

It clears the head when things are said too brilliant to be bright!

It keeps the stars from the golden bars and the lips of the tipsy town;

So, here's to strong, black coffee – drink it up, drink it down!

With a fol-de-rol-dol and a fol-de-rol-dee, etc.”

(It should be

noted that Mocha here refers to a coffee bean of the Arabica family, not the coffee/chocolate beverage

favoured by those who Untermeyer would, I presume, class as men who get drunk,

or, worse, women.)

Now, The Moo Man, a documentary directed by

Andy Heathcote and Heike Bachelier, adds another dimension to our daily

anxieties, for, if you’re confident enough in your sense of self and social

standing to admit to taking milk in your coffee, you had better think long and

hard about what sort of milk drinker you want to be.

The film,

which made the official selections at both the Sundance and Berlin

International festivals earlier this year, offers an intimate and episodic portrait

of life on a small, independently-run dairy farm on the Pevensey marshes in

East Sussex, with insights into the relationship between man, beast and,

ultimately, milk: there are scenes showing Farmer Hook reminiscing on the life and

death of Kato, a young steer, as he counts out the vacuum-packed cuts of meat he

has become (unlike most other dairy farmers, the Hooks keep males rather than

killing them at birth); a seaside photo-shoot with Ida, a star heifer (pictured above), intended

to publicize the benefits of raw, organic milk; the mixture of tenderness and practicality

with which Farmer Hook tends to an ailing cow (a metal detector is involved);

and the family’s excitement as automization – in the form of a mini milk

bottling plant – arrives on the farm, bringing with it hopes of reaching new

markets (an opening sequence showing the brothers filling and capping bottles

by hand in their kitchen is indicative of the size of their operation).

Filmed over

four years, the narrative observes Farmer Hook and his herd of fifty-five heifers

as they struggle to stay afloat against a backdrop of disappearing traditions,

changing tastes, health scares, and the supermarket behemoths that call the

shots. We learn that, in Britain, one family-run farm closes every day, a

statistic echoed around the world; of course, this isn’t to say that we’re

shunning milk en masse, in our coffee, tea or otherwise – it doesn’t take a

social anthropologist to banish any idea of Britain as a nation of

Untermeyer-style strong men.

Add to this

that the cost-price of a litre of milk is 34p, but that most supermarkets pay only

27p per litre and it becomes apparent that to opt into this system is to condemn

the farmer to a life of poverty and reliance on tax-payer subsidies.

A general UK release

for The Moo Man is scheduled for July

12 but, in order to achieve this (“releasing a film is an expensive business”,

the directors point out), a Kickstarter campaign has been set up – to cover the

cost of production (“We’re planning the best trailer you’ll ever see”),

promotion, distribution, and, one hopes, enough hay to keep the cows happy for quite

some time; an opportunity to wipe away your milk moustache and put your money

where your mouth is: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1438468236/bring-the-moo-man-to-uk-cinemas

June 10, 2013

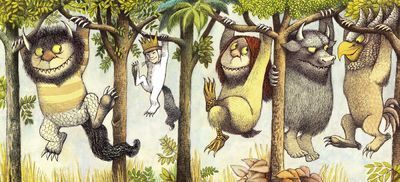

Maurice Sendak, Google and the TLS

© Maurice Sendak / Random House Children’s Publishers UK

by Lucy Dallas

The Google Doodle today is in honour of Maurice Sendak, as this would have been his 85th birthday. It is a dare I say, mash-up of three of his books; Where The Wild Things Are, inevitably; In The Night Kitchen, another brilliant early work but less well-known (partly because the hero's clothes fall off and he is almost baked alive in an oven by three giant bakers who all look just like Oliver Hardy), and Bumble-Ardy, a later story involving a pig's riotous birthday party.

In 1970, the TLS printed a speech Sendak gave on receipt of the Hans Christian Andersen Illustrator's Award at the Bologna Children's Book Fair, which you can read here (though beware, the reproduction is a little muddy): "As a child I felt that books were holy objects, to be caressed, rapturously sniffed, and devotedly provided for".

In an interview with Terry Gross from NPR (I can't tell exactly which one, I'm afraid), he said, in response to her question asking for his favourite comments from readers:

'Oh, there’s so many. Can I give you just one that I

really like? It was from a little boy. He sent me a charming card with a

little drawing. I loved it. I answer all my children’s

letters–sometimes very hastily–but this one I lingered over. I sent him a

postcard and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, “Dear

Jim, I loved your card.” Then I got a letter back from his mother and

she said, “Jim loved your card so much he ate it.” That to me was one of

the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was

an original drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.'

Taste the Mermaids

By Peter Stothard

A friend in Washington DC calls to say how much he likes the opening pages of my Alexandria: The Last Nights of Cleopatra.

That's nice but only the opening pages?

Well, there were some other parts he had - and liked - too.

Which parts? How so?

The US edition from Overlook Press does not appear for a month or so.

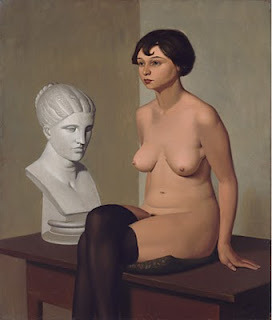

And when it arrives, it will certainly include the whole text, including the pages that relate, for example, to the nude with plaster bust (above).

Ah, I get it - eventually.

Bits of the British book, it seems, are available as a Google taster.

I did not know that happened.

But, if anyone else wants a taste of some mermaids, this the link.

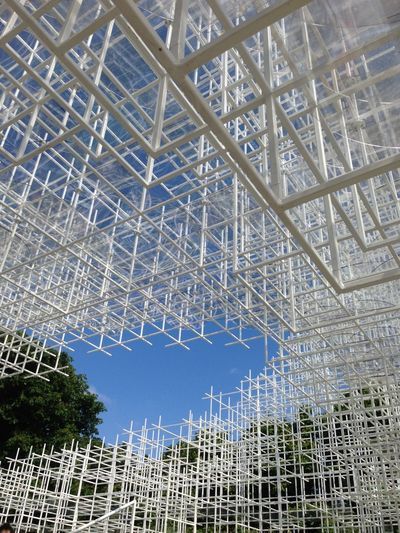

Anarchic architecture

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Art

for all? “This is architecture for all”, explained Hans Ulrich Obrist, the co-director

of the Serpentine Gallery, at a talk on Saturday afternoon to mark the opening

of this year’s summer pavilion. The white steel, grid-based structure, like a crosshatched

drawing or an intricate pile of hollowed-out sugar cubes, is the work of Sou

Fujimoto. He is the third Japanese architect invited to design the Serpentine’s

Pavilion – and their sensitive approach has produced some of the more exquisite

creations, including Toyo Ito’s pavilion of interlocking triangles and

trapezoids in 2002.

The

Serpentine’s Pavilion programme, now in its thirteenth year, pushes the language

of architecture and, importantly, makes it available to all – “from the flâneurs

in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, to the joggers using the structure as a

stretching frame”, observed Obrist with a smile. This year’s Pavilion is no

exception, and is perhaps one of the best yet.

Taking

my seat for Fujimoto’s talk, I realized that securing a ticket was pleasingly

unnecessary. A number of passers-by

climbed on the structure, settling around the sides and almost over our heads

to listen-in (my fold-up chair on ground level felt slightly boring in

comparison), while Fujimoto discussed his design and process with Obrist and

fellow Serpentine director Julia Peyton-Jones.

“My

thinking is in dialogue with my hand”, Fujimoto told us. For him, designing is

an endless, often private, process of sketching and physical experience which was

not compromised in this Pavilion project despite the time pressure (an

architect has only six months from invitation to completion of the Pavilion,

and it requires planning permission like a permanent structure). In the early

stages, Fujimoto found himself twisting and stapling sheets of paper to find

shapes that created interesting shaded areas or axes. Then he would cut away or

add parts “to make things more mysterious. One snip can change the expectations

of a space”.

The

Japanese fascination with Bonsai trees comes to mind, especially in relation to

the title of the talk, “Architecture as Forest”. But Fujimoto’s meaning here is

also the idea of a building as a landscape. The key theme of his career has

been the relationship between architecture and nature; and with this pavilion,

he wanted to create a structure “that vanishes into its surroundings but is at

the same time outstanding”.

Fujimoto

described it as a “mist” or a “cloud” rising between the heavy brick of the

gallery and the park. It is “a space made by almost just space. The

transformation of a solid thing, a steel grid, into something translucent”. Choosing

to use differently scaled cubes helped him to achieve a diversity of densities

– some areas are more porous, whereas other parts, with smaller grids, make denser

patterning and more shadows. Yet the tonnes of white steel produce a building of

ineffable lightness. I can imagine the usual British summer weather – grey and

white skies – accommodating the Pavilion as beautifully as Saturday’s full sun.

Clouds also have a strong association with the ether of the digital age (Apple’s

“iCloud” etc) and the geometric grid taps into this, though perhaps it is

somewhat at odds with Fujimoto’s untechnical design process.

Peyton-Jones

labelled Fujimoto “anarchic” – “he is a radical in the way he thinks about architecture

and re-defines how humans use space”. For example, his Tokyo Apartment (2010) challenged

architectural taboos by deliberately putting a staircase in front of a window. Fujimoto

stated that unexpected juxtapositions like these are playful but they also reflect

the complex order of nature, which is not controlled or neat: “there is a

richness from over-laying two requirements like a window and a staircase, or

having tables at various levels. For some people it’s a table, but at another

point, for another person, it’s seating. I choreograph multi-directional space”.

Architecture for function (where it has one meaning and one use) contrasts with

Fujimoto’s interest in architectural relativity (inspired by Einstein) where a

building can evince a never-ending sequence of interactions and spaces.

To

explain more clearly, Obrist pulled out a page from Fujimoto’s Primitive Future (a book as

multi-functional as his buildings – it’s a design guide, a sketchbook, a

manifesto, a philosophy . . . ). As a research process ten years ago, Fujimoto separated

musical notes from their stave. The strong, linear stave represents an

underlying, continuous form that defines our world (like the pavilion’s grid).

But this pre-defined form can emerge in a different way according to how a note

(an individual human) interacts with it. Fujimoto’s pavilion can be used as a

score to be played by anyone, and it doesn’t fail to produce a tune.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers