Anarchic architecture

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Art

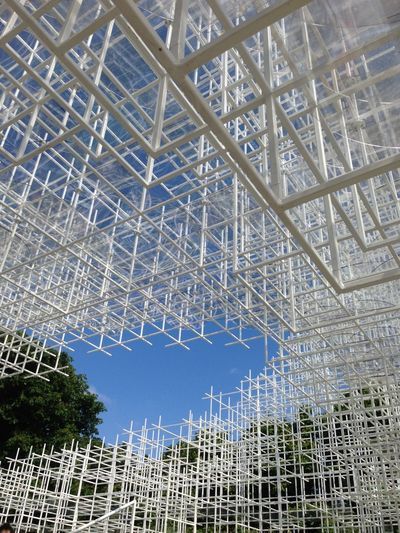

for all? “This is architecture for all”, explained Hans Ulrich Obrist, the co-director

of the Serpentine Gallery, at a talk on Saturday afternoon to mark the opening

of this year’s summer pavilion. The white steel, grid-based structure, like a crosshatched

drawing or an intricate pile of hollowed-out sugar cubes, is the work of Sou

Fujimoto. He is the third Japanese architect invited to design the Serpentine’s

Pavilion – and their sensitive approach has produced some of the more exquisite

creations, including Toyo Ito’s pavilion of interlocking triangles and

trapezoids in 2002.

The

Serpentine’s Pavilion programme, now in its thirteenth year, pushes the language

of architecture and, importantly, makes it available to all – “from the flâneurs

in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, to the joggers using the structure as a

stretching frame”, observed Obrist with a smile. This year’s Pavilion is no

exception, and is perhaps one of the best yet.

Taking

my seat for Fujimoto’s talk, I realized that securing a ticket was pleasingly

unnecessary. A number of passers-by

climbed on the structure, settling around the sides and almost over our heads

to listen-in (my fold-up chair on ground level felt slightly boring in

comparison), while Fujimoto discussed his design and process with Obrist and

fellow Serpentine director Julia Peyton-Jones.

“My

thinking is in dialogue with my hand”, Fujimoto told us. For him, designing is

an endless, often private, process of sketching and physical experience which was

not compromised in this Pavilion project despite the time pressure (an

architect has only six months from invitation to completion of the Pavilion,

and it requires planning permission like a permanent structure). In the early

stages, Fujimoto found himself twisting and stapling sheets of paper to find

shapes that created interesting shaded areas or axes. Then he would cut away or

add parts “to make things more mysterious. One snip can change the expectations

of a space”.

The

Japanese fascination with Bonsai trees comes to mind, especially in relation to

the title of the talk, “Architecture as Forest”. But Fujimoto’s meaning here is

also the idea of a building as a landscape. The key theme of his career has

been the relationship between architecture and nature; and with this pavilion,

he wanted to create a structure “that vanishes into its surroundings but is at

the same time outstanding”.

Fujimoto

described it as a “mist” or a “cloud” rising between the heavy brick of the

gallery and the park. It is “a space made by almost just space. The

transformation of a solid thing, a steel grid, into something translucent”. Choosing

to use differently scaled cubes helped him to achieve a diversity of densities

– some areas are more porous, whereas other parts, with smaller grids, make denser

patterning and more shadows. Yet the tonnes of white steel produce a building of

ineffable lightness. I can imagine the usual British summer weather – grey and

white skies – accommodating the Pavilion as beautifully as Saturday’s full sun.

Clouds also have a strong association with the ether of the digital age (Apple’s

“iCloud” etc) and the geometric grid taps into this, though perhaps it is

somewhat at odds with Fujimoto’s untechnical design process.

Peyton-Jones

labelled Fujimoto “anarchic” – “he is a radical in the way he thinks about architecture

and re-defines how humans use space”. For example, his Tokyo Apartment (2010) challenged

architectural taboos by deliberately putting a staircase in front of a window. Fujimoto

stated that unexpected juxtapositions like these are playful but they also reflect

the complex order of nature, which is not controlled or neat: “there is a

richness from over-laying two requirements like a window and a staircase, or

having tables at various levels. For some people it’s a table, but at another

point, for another person, it’s seating. I choreograph multi-directional space”.

Architecture for function (where it has one meaning and one use) contrasts with

Fujimoto’s interest in architectural relativity (inspired by Einstein) where a

building can evince a never-ending sequence of interactions and spaces.

To

explain more clearly, Obrist pulled out a page from Fujimoto’s Primitive Future (a book as

multi-functional as his buildings – it’s a design guide, a sketchbook, a

manifesto, a philosophy . . . ). As a research process ten years ago, Fujimoto separated

musical notes from their stave. The strong, linear stave represents an

underlying, continuous form that defines our world (like the pavilion’s grid).

But this pre-defined form can emerge in a different way according to how a note

(an individual human) interacts with it. Fujimoto’s pavilion can be used as a

score to be played by anyone, and it doesn’t fail to produce a tune.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers