Peter Stothard's Blog, page 61

May 23, 2013

Once a problem play, always a problem play?

By MICHAEL CAINES

It’s a notorious moment: in the fourth act of his flawed yet fascinating play An Enemy of the People, Ibsen has the protagonist, Dr Thomas Stockmann, denounce the rule of the majority. It’s the elite who should rule.

You can guess where this kind of talk will lead. At the Young Vic, where the play is currently running in a new version by David Harrower, under the pithier, more Cagney-esque title Public Enemy, Stockmann ends up giving a Nazi salute, and telling the audience: “You should be exterminated like vermin, all of you, before you poison the whole country . . .”.

As Arthur Miller put it, however, prefacing his own alteration of the play for the age of McCarthyism, the speech has to be understood in a structural context: “in some important respects”, it contradicts “the actual dramatic working-out of the play”.

The town where Stockmann lives depends on the summer visitors to its famed public baths for its living, but the doctor has discovered that the water supply is contaminated and, far from making people better, is more likely to kill them off. The town, sure enough, won’t have it, driving him, out of sheer frustration, to condemn them for thinking that they know better than him. The majority of people may have might on their side, he declares, but they are never right. Only a (smarter) minority may be right. The politicians and the press, meanwhile, call the tune for the ignorant masses to follow. The truth doesn’t stand a chance against this alliance of ignorance and megalomania.

Since Stockmann is addressing a public meeting at this point, the atmosphere turns distinctly nasty; his wife Katrina suggests that they leave by the back door.

All too easily lost in the mêlée is Ibsen’s real point: that there is not an “aristocracy of birth, or of the purse, or even . . . of the intellect” but an “aristocracy of character, of will, of mind – that alone can free us”. But this is to quote Miller quoting Ibsen speaking at a real public meeting, a workers’ club, and it offers the later playwright a congenial justification for excising “those examples which no longer prove the theme – examples I believe Ibsen would have removed were he alive today”. “The man who wrote A Doll’s House, the clarion call for the equality of women, cannot be equated with a fascist.”

Stockmann’s intellectual elitism has always disconcerted theatre audiences and critics: not everybody has shared Miller’s convictions that Ibsen is in the right. And the reviewers often take the big speech to be the most significant part of the play.

As staged by Jones, Stockmann (charismatically, likeably played by Nick Fletcher) delivers his rant to the Young Vic audience itself, hogging the microphone (we’re in a mid-twentieth-century Norway here, not the 1880s), rather than haranguing a crowd on stage. “If this is what you get by voting for them”, he says of the politicians, “don’t vote! Keep your dignity. . . I never vote.” Fletcher retains a certain flexible liveliness here, as though he really were making an impromptu speech – rephrasing when he jumbles his words, saying “bless you” to an unscripted interruption from the audience.

The press night crowd know how to behave; they don’t respond to the rhetorical questions which he presses on us. But imagine the critics sitting there, confronted with this supposedly transformed man (in fact, the spirit of individualism and its attendant dangers are plain from the start) condemning them as the "enemies of truth"; it seems to have been rather difficult after that to apply the kind of clear thinking about context that allowed Miller to see through the ranting.

No wonder they have to identify Stockmann's big speech as a “Brechtian coup de théâtre”, the speech of a “disillusioned prophet in his own country, turned crazed proto-fascist”. Or as a “breathtaking assault on democracy” through which the director, Richard Jones, rejects “maverick individualism” along with “endemic complacency” – a speech that “hovers between absolute candidness and repellent megalomania”. “At best he is arguing for greater personal responsibility; clearly what he’s really advocating is closer to fascism.”

There’s nothing new in this uneasiness about the play (once a problem play, always a problem play?), nor in the idea that it’s entertaining despite its apparent faults. Ibsen intended An Enemy of the People as an immediate riposte to the majority view of its predecessor, Ghosts (1882), and its supposed indecency (viz, daring to raise the moral problem of marriage again, after A Doll’s House, and the related medical problem of hereditary syphilis). If Ghosts was, as one newspaper had it, an “open drain”, An Enemy of the People embraces the same metaphor of pollution. Controversy is its natural element.

Ibsen himself didn’t know exactly what he’d written. Was it a comedy or a serious drama? And once the play came over to England, the critics couldn’t work it out, either. One anonymous reviewer of a public reading of the play at the Haymarket Theatre in 1890 thought that the dialogue was “pithy and epigrammatic” but that the play would not succeed in England as an “acting drama”. Another thought it “rather commonplace” for anyone but the Ibsen devotee. A third, incredibly, called it “absolutely wholesome and breezy from end to end”; it’s the Ibsen play that “may fearlessly be produced before an English audience verbatim et literatim”.

That leap into madness in Act Four made a disturbing impression on twentieth-century critics, too. Charles Morgan (whose selected reviews will be reviewed in turn in a future issue of the TLS), in 1928, thought it dubious in its refusal to distinguish between democracy in politics and, say, medicine (Stockmann's is clearly a one-doctor town). James Agate, in 1939, could hardly help seeing in the outgunned protagonist’s attack on the rule of the majority a foretaste of “Democracy’s quarrel with Dictatorship”. At least it had been “an intensely exciting evening” at the Old Vic. More recently, at the National Theatre in 1997, in Trevor Nunn’s staging of a version by Christopher Hampton, the TLS’s reviewer Peter Kemp observed that Ian McKellen avoided turning Stockmann into a “caricature” – “an incipient Fuehrer of the fjords” – “by making it clear that Stockmann is goaded into overstatement by the storm of execration he has provoked”. And only a few years ago, there was a production at the Arcola that got it wrong, according to John Peter, by representing Stockmann as a kind of freedom fighter, instead of a monster created by the majority and their “cosy supremacy”.

One of the few new points to emerge since the 1970s is that the play lies behind Stephen Spielberg’s film Jaws. But there the equivalent Stockmann character at least gets to say “I told you so; there’s something in the water . . . .”

May 22, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

The United States has spawned many millenarian sects, but what makes the internet religion emanating from Silicon Valley – complete with its own prophets, salvific narrative and eschatology – different from all of them is the way it has insinuated itself in our lives. Michael Saler reviews two new books about the internet as force for (mostly) evil, exposing cyber-culture’s totalitarian tendencies, messianic pretensions, technological amnesia, “complete indifference to history” and contribution to the growing disparity in wealth and power in Western populations. Even more (so far) than the internet, “the car and truck reshaped everything” – people’s lives, the environments in which they lived. Somewhat akin to developments in the virtual realm, though, “many of the changes wrought by cars were embodiments of one fantasy or another”. Paul Barker reviews a “richly informative” exploration of the internal combustion engine’s impact on England. Coventry was “the Metropolis of Motordom” in the 1930s, and Dagenham became “the Detroit of Europe”. Now, Barker writes, “the most flourishing parts of the British economy are huge sheds in truck-filled acres of parking space near a motorway junction, all serviced by online ordering”.

This world had its proleptic poet in J. G. Ballard; and it haunts the imaginations of his most talented admirers, such as Will Self and Martin Amis. The latter has “a walk-on part” in Greg Bellow’s memoir of his famous father, Saul (above) – but he played a slightly more important one in the great American novelist’s dreams, according to our reviewer Clive Sinclair. “A Lady, tall, dark, strongly built, wishes to meet a gentleman going to Socialist colony, with a view to union”: this and other personal ads like it graced the radical periodicals of the fin de siècle, a study of which is reviewed by Leah Price. They generated “what theorists of online media call a long tail: niche monthlies or weeklies addressed to a small but loyal following whose subscriptions defined their identities”. Sound familiar?

Alan Jenkins

May 17, 2013

Iggy Pop, the one and only

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

George Christie, the chairman of Glyndebourne Opera, said something very interesting (to me at least) on the radio the other week. According to him, a lot of people in their twenties, thirties or forties make a transition in their music-listening habits from pop/rock to classical music.

This certainly happened to me in my twenties, when I made a conscious and deliberate switch: the 80s were in danger of becoming the lost decade, music-wise, and I knew there was a whole repertoire of classical music out there waiting to be discovered. The film Amadeus fired many of us with an enthusiasm for Mozart; Round Midnight put people on to jazz. Music suddenly became more interesting and rewarding again.

The work of Gustav Mahler held particular appeal and I now know that I’ll be listening to his symphonies and song cycles for as long as I’m still listening to music. The same goes for Dmitri Shostakovich – well, the symphonies mainly: Nos 4, 5, 8 (in the recording by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by its dedicatee Yevgeny Mravinsky), 10 and 15. Sibelius became another favourite.

And then there was Schoenberg and Berg, and Bartók, and Messiaen, and Ligeti . . .

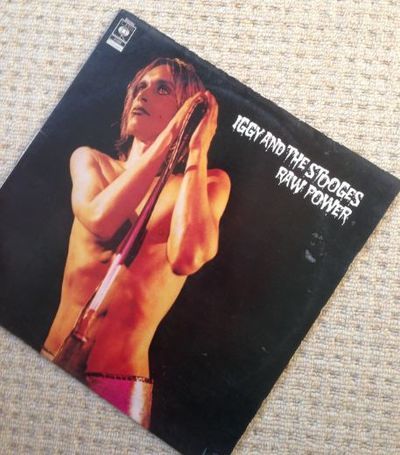

But the music you grow up with stays with you and, in my case, none more powerfully than that of Iggy Pop (né James Osterberg) and his Detroit band The Stooges. This was music not to grow up to. Their album Raw Power (1973) is the one from my adolescent years that I know I could not do without – it represents nihilism raised to an art form. Will Hodgkinson recently described it in The Times as “one of the greatest – and nastiest – rock albums”.

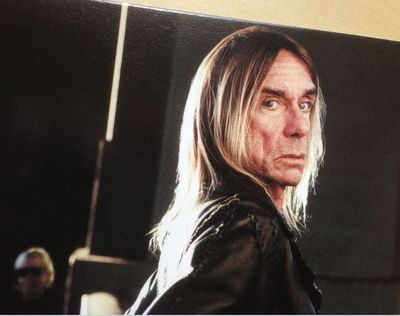

Iggy and the Stooges re-formed a few years back and gave a compelling performance at the Hammersmith Odeon three years ago, the sexagenarian Iggy displaying the energy of a twenty-year-old. There were fewer crowd dives than before – a relief. The audience was one big midlife crisis. The music (quite loud) was driven by the guitarist James Williamson, who left the Stooges and went on to become a high-up in Sony Electronics, took early retirement and returned to the band. Good career move.

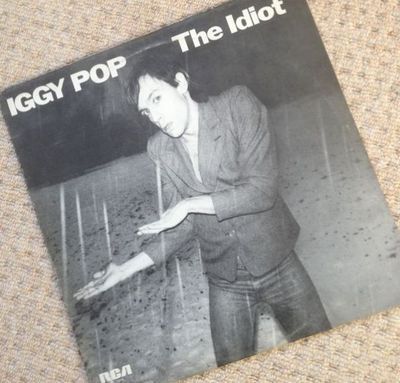

Iggy Pop himself has of course had an on-and-off-the-rails solo career in between the two Stooge incarnations. David Bowie salvaged it in the 70s, and worked with him on two of his best albums, The Idiot, whose cover (below) echoes Bowie's Heroes, and Lust for Life. (Danny Boyle made great use of the title song in the film Trainspotting.) Bowie went on the road with him – his backing vocals (and keyboard) can be clearly heard on the brilliantly shambolic live album TV Eye. “China Girl” was a hit for Bowie but there’s a better version on The Idiot. There were some other fine moments later: “I’m Bored”, “I’m a Conservative”, and, as if to counter that, the hilarious “Don’t wanna be no Squarehead”.

It's heartening to discover that Johnny Depp is a big Iggy fan. His account of first meeting his hero is very funny (it's on the World Wide Web). Even more hearteningly, Iggy and the Stooges have released a new record, Ready To Die, and it’s really not bad. James Williamson’s guitar playing is as menacing as ever, and Iggy’s remarkable voice (well, you either love it or . . . ) sounds in pretty good shape.

Iggy Pop has always written and sung wonderful ballads, and there are a couple on this one, including the majestic “Beat That Guy”, which I have listened to eighty times, at a conservative estimate: “Runnin’ out of space / I’ve run out of time / I’m runnin’ out of reasons / Though I don’t know why” . . . . Thankfully he shows no signs of ageing gracefully. The raw power is still there.

May 16, 2013

All’s well that’s Boswell

By MICHAEL CAINES

Unless you’re an avowed enemy of the biografiend, today is a good day to raise a glass to the art of biography and, in particular, to James Boswell. This is the 250th anniversary of Boswell’s first meeting with his subject, Dr Johnson – or, as James Knox, the chairman of the Boswell Book Festival put it this morning, Boswell’s “creation” Dr Johnson – at the house of the actor and bookseller Thomas Davies, in Russell Street near Covent Garden.

The book festival, which opens tomorrow at Auchinleck House, was preceded this morning by a gathering at the house of the publisher John Murray on Albemarle Street – ahead of a symposium hosted by King’s College London and Dr Johnson’s House, Professor Gordon Turnbull and the actor John Sessions made an excellent double act, the first running lightly through the story of Boswell’s life before Johnson, the second supplying the necessary range of accents – Ayrshire, Cockney, Lichfield – to bring the occasion to life.

For an audience, the speakers had some of Boswell’s descendants, both lineal and literary, biographers, academics, hangers-on (guess which category I put myself in); for a set, they had the magnificent Murray drawing room. “Literary London” seldom looks so good at half past eight in the morning.

Raise a glass to booksellers, too, then; Boswell knew the first John Murray, and Boswell and Johnson share their Russell Street plaque with Davies. In fact, Davies is the crucial link between them, and if his wife Susanna wasn’t so notoriously beautiful, Johnson might not have enjoyed calling there so often. (Professor Turnbull pointed out that Boswell didn’t record in his journals that she was present at the celebrated first meeting, but added her name to the version in his Life of Johnson; a telling detail, since when the Doctor put down the unknown young Scot, for the first of many times, he was very likely showing off in front of her.)

Boswell had hoped to meet Johnson through their mutual friend Thomas Sheridan, but by the time he got to London, in 1762, they were no longer on speaking terms. It was Davies who invited Boswell to meet Johnson, initially on Christmas Day, 1762, when Johnson opted instead to go to Oxford, and Boswell had to settle instead for Robert Dodsley and Oliver Goldsmith, “a curious, odd, pedantic fellow with some genius”, with whom he disagreed over the merits of Shakespeare and Thomas Gray.

The meeting that took finally place in the back-parlour of Davies's shop, around 7 in the evening of May 16, 1763, wasn’t planned. Boswell later “remembered” that Davies had announced Johnson’s arrival with a presciently symbolic line from Hamlet, as if he were alerting the prince to the presence of his father’s ghost: “Look, my Lord, it comes . . .”. Davies’s role doesn’t end there. He reassured the would-be acolyte that Johnson actually liked him, despite the initially ambiguous reception, and later that it would be acceptable for Boswell to call on Johnson. When Boswell was back in Scotland, he could rely on Davies for publishing advice and reassurance despite the lack of news from Johnson himself: “I am sure he has a true respect for you”, he wrote in August 1766, “but you know the Indolence of his temper”.

As Kate Chisholm wrote in the TLS recently (the whole piece can be read for free here), it is through Boswell’s Life of Johnson that we know about his views on “women preachers, Scottish savages, the temptations of the theatre and a man who is tired of London” – to the extent that this biographical “creation”, to use James Knox’s term again, eclipses the author of the Rambler, the Idler etc. “How, then, do we go back to read Johnson as if the Life, with all its anecdote and conversation, did not exist?”

It’s a good question. What greater tribute could a biografiend wish for?

May 15, 2013

In this week’s TLS – A note from the History editor

On the face of

it, the nineteenth-century Russian writer Nikolai Leskov and the early

twentieth-century American writer Sherwood Anderson would seem to have very

little in common. Leskov came from “a long line of priests”, and his work was

inspired by the traditions of Russian orthodoxy. Anderson was a “hardworking

businessman” who, according to literary legend, walked out of his office at a

paint factory one day, and devoted the rest of his life to writing “fables of

estrangement”. But both A. N. Wilson, reviewing new translations of Leskov’s

stories, and Michael Dirda, on a Library of America edition of Anderson, see a

connection between their subjects and Anton Chekhov. It was Leskov who prepared

the ground for Chekhov, Wilson argues. But where Chekhov’s characters seem

universal types, Leskov’s remain “pungently” Russian. Dirda sees Anderson

himself as an equivalent “John the Baptist” figure in the development of the

American short story, foreshadowing William Faulkner, for example, who declared

that Anderson was “the father of my generation of American writers”. Anderson’s

“distinctive tenderness for his characters, despite all their flaws and

foibles” reminds Dirda not of American forebears, however, but of Russian ones:

Turgenev – and Chekhov.

In an age of

academic specialization, history books that establish a new orthodoxy across a

great swathe of time and distance are increasingly rare. But Theodore K. Rabb

believes that Geoffrey Parker’s magnum opus, Global Crisis, does precisely

that. Parker makes a “monumental statement about the nature of

seventeenth-century history”, which sets the “General Crisis” of that period

firmly at the centre of its history. If the “essential background” is the

Little Ice Age, “misguided policy decisions” of leaders across the globe

account for the century’s “world-wide agonies”.

In Commentary,

Mark Davies offers an intriguing new candidate as the model for Lewis Carroll’s

(and John Tenniel’s) Mad Hatter.

David Horspool

May 14, 2013

Very shirty

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“A shirt is the closest to the heart, so that is why I use shirts. The person is there.”

Thus the Finnish sculptor Kaarina Kaikkonen whose latest work, co-commissioned by the Brighton Festival, is on exuberant display in the high-ceilinged Fabrica art gallery, a former Regency church in the centre of Brighton.

If you feel you've become too sexy for your shirt, why not send it to Kaarina Kaikkonen? She clearly has a use for it. The shirts in this exhibit were donated by Brighton residents and will then be passed to Oxfam.

Kaikkonen is, according to the display leaflet, “best known for several major works using hundreds of discarded men’s jackets, items that have a highly charged and personal significance for her. Though ambiguous in meaning, her works evoke associations of personal loss, collective memory and local histories”.

Her work has been displayed outdoors to wonderful effect, where the shirts take on the appearance of linked soaring kites.

For good measure the artist draped the clock tower in the centre with items of clothing (see below), lighting up a dull sky.

The shirt hang, or "Blue Route", is on until May 27.

May 9, 2013

Brighton ballads

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Almost

certainly a first: three Dutch poets reading in Brighton. On the opening

weekend of the three-week-long Brighton Festival, the Frisian threesome were

joined by one French poet for an event organized by Modern Poetry in Translation. It was easy to tell the French poet:

she was the one wearing the beret. The four - Menno Wigman, Ester Naomi

Perquin, Valérie Rouzeau and Toon Tellegen - were eloquently introduced by the

editor of MPT, Sasha Dugdale.

The

Brighton Festival traditionally has a Guest Director and this year it’s the

turn of Michael “We’re Going on a Bear Hunt” Rosen, whose enthusiasm for Erich

Kästner’s Emil and the Detectives is

evident in the programming. But as is usually the case, the choice of events is nicely

varied. A couple of years ago, the organizers cheekily (I thought) invited

Aung San Suu Kyi to be their guest director. I don’t imagine she had much of a

hand in organizing it, but she obliged with a gracious introduction to the

programme; there were a number of performances relating to The Lady, of, er,

varying quality. Last year the guest director Vanessa Redgrave saw the

invitation as an opportunity for a mini season of her own films. Brian Eno, a

few years back, gave things a strongly musical flavour.

The MPT

poetry reading was a success, partly because (in my case at least) three of the

poets were unfamiliar. First up was Menno Wigman, who is currently city poet of

Amsterdam, in which role, he explained, he is occasionally asked to write

elegies for people who have died alone or on the street (he read one

of these). Wigman has been described as the “dandy of disillusion” and he

writes melancholy poems of urban solitude and despair, eloquently conveyed by

his translator David Colmer.

Ester

Naomi Perquin, meanwhile, has drawn on her experience working as a guard in a

prison in her home city, Rotterdam. Her poems, on the evidence here, are

quirky, occasionally confessional, with arresting lines: “Strange tracks lead

down to the drink”. Her work has been Englished by the eminent Dutch translator

Paul Vincent (who wasn’t able to attend). Rather charmingly Perquin chose to

read one of her poems in English, claiming that Vincent’s version was

better than the original.

Tellegen’s expressive reading of a long sequence in Dutch made demands on the audience that Judith Wilkinson’s translations (read by David Constantine) didn’t quite meet:

something profound and metaphysical but . . . . I found more nourishment in

some of Tellegen’s poems in the MPT volume: “If you were to ask me: how old

would you like to be, / I would say: 2420 years. / For then, as a boy in

Athens, / I would have seen / Aristophanes’ plays”, . . .

Valérie

Rouzeau has published twelve collections. Her work has been superbly translated

into English by Susan Wicks as Cold

Spring in Winter (2009), which was described by the TLS reviewer Patrick McGuinness as a “book of rare cumulative

power”; indeed Wicks won the Scott Moncrieff Prize for translation for her

rendition of Rouzeau’s lament for her dead father, Pas Revoir. As Rouzeau exclaimed at one point as Wicks was reading

her translations of new work, “She’s such a fucking good translator!” Wicks writes that “preserving the essence of

Rouzeau’s work in English isn’t easy”, and that “the boldness of the poetic

procedures in French was asking an equivalent boldness of me as their translator”.

She describes her language as “contemporary, slangy, playful, childlike . . .

“.

The opening of Pas Revoir

illustrates the challenges for the translator: “Toi mourant man au téléphone pernoctera

pas voir papa. / Le train foncé sous la pluie

dure pas mourir mon père oh steu plaît tends moi me dépêche d’arriver ».

Wicks renders it: “You dying on the

phone my mum he will not last the night see dad. / The train a dark rush under

rain not last not die my father please oh please give me the get there soon”.

Elsewhere Wicks ingeniously opts for “by the why dopen doors” for “près des

portes béates”.

Rouzeau’s

most recent collection, Vrouz (how,

one wonders, will Wicks translate that?) won the Prix Apollinaire in 2012.

Rouzeau has that slightly baffling French habit of reading fast, almost like a

hangover from the classroom. But the new work, more upbeat perhaps, had her inimitable stamp: “Don’t rent a lorry I can move your stuff / I’ve got a little

van your things will fit in fine / Smile you’re just moving house you’re off to

better days . . . “.

May 8, 2013

In this week’s TLS – A note from the History editor

From its very beginnings, the story of America has resisted “attempts to

impose a particular shape and meaning”, in the words of Amanda Foreman.

Reviewing the Harvard historian Jill Lepore’s collection of essays on

American origins, Foreman observes that, from Captain John Smith in

Jamestown in the early 1600s, to successive American Presidents in their

inaugural speeches, “truth has been, not the standard-bearer of history, but

the servant of politics”. Lepore’s own approach to her country’s past

responds to overarching views of a nation imbued with manifest destiny by

breaking them down into “microhistories”. These studies of past lives take

“small mysteries about a person’s life as a means to exploring the culture”.

The larger mysteries of the brain are Raymond Tallis’s subject, specifically

the advances in functional magnetic resonance imaging, and how much they can

tell us. Some contributors to a collection on the subject are running before

they can walk, worrying about the legal and ethical implications of reading

a person’s thoughts before any such thing is within the realms of

possibility.

The frontiers of science, and as yet unrealized breakthroughs, are perhaps

more properly the province of science fiction. Michael Saler addresses a new

edition and critical study of one of the first examples of the genre, Frankenstein

by Mary Shelley. Though “packaged as a philosophic novel”, and taking in

classical and Christian tropes as well as the more familiar Gothic,

Shelley’s precocious production (she was nineteen when she wrote it) was

also an exploration of the scientific cutting edge. Luigi Galvani and

Humphry Davy would have been sources of inspiration, as would her husband

Percy’s own dabblings in experimental chemistry.

The popularity of fictional versions of servants’ lives, from Upstairs,

Downstairs to Downton Abbey, has made the task of recovering the

realities of lives in service even more worthwhile. Paul Addison finds that

Lucy Lethbridge’s Servants is “social history at its most

humane and perceptive”.

David Horspool

NB See the TLS website for our Poem of the Week, "Song" by George Barker, and the contents page in full for this week's issue.

May 5, 2013

A forbidding shadow . . .

By MICHAEL CAINES

Today is the bicentenary of Søren Kierkegaard’s birth – an event that is being celebrated, later in the year, with Fear & Trembling in Berlin (a play), seduction in Israel (an evening of music and film in Tel Aviv, inspired by the “Johannes the Seducer” part of Either/Or) and other events, listed here, including an exhibition in Copenhagen, where he was born, inspired by his battle with Hans Christian Andersen.

Philatelists will no doubt mark the occasion by splashing out 8 krone for the philosopher’s stamp:

Others may wish to swot up on the rhetoric of spiritual anguish etc.

Not that it will help them, if the author himself is to be believed. In Alastair Hannay’s translation of the philosopher’s journals:

“nothing is learnt from history. The illustrious of bygone times stand there in their glory; even persecution and the like have their attraction. No closer understanding is conveyed. And then a youngster rushes off and misunderstands . . . .”

Then again, Kierkegaard has characteristically hard words for those who do take heed:

“Many arrive at a life’s result like schoolboys; they cheat their teacher by cribbing from the key in the maths book, without having done the sum themselves.”

These views didn’t prevent him from looking into the future and seeing the kind of figure he himself would cut one day. Without claiming to be a thoroughgoing authority on his oeuvre, I’m struck by the conviction, in the works that I do know, behind his repeated glances in the direction of posterity:

“Ah, once I am dead, Fear and Trembling alone will be enough to immortalize my name as an author. Then it will be read, and translated into other languages. People will come to the point of trembling at the frightful pathos in the book. Yet when it was written, when he who is considered its author went about in an idler’s disguise, looking like flippancy, wit, and frivolity itself, no one could properly grasp its seriousness. O ye fools!”

Does Kierkegaard matter today? Well, it's funny you should ask . . . there's a piece on his contemporary relevance forthcoming in the TLS.

An 800-page biography appeared a few years ago; see Jonathan Lear’s superb review for the TLS to get an idea of the idler’s disguise and the world out of which Kierkegaard’s extraordinary works emerged. And see Jonathan Rée’s equally fine piece from 1998 for an account of Kierkegaard’s legacy and the problems of translating and trembling in his presence. To qualify/contradict what I’ve said about his concern about his own status in the future, though, here’s a request Lear quotes from the end of the Concluding Unscientific Postscript:

“My wish, my prayer, is that, if it might occur to anyone to quote a particular saying from the books, he would do me the favor to cite the name of the respective pseudonymous author”.

(“His wish comes to mind every time I am in the ‘Kierkegaard’ section of a bookstore”, Lear adds.)

For Laura Riding, however, writing in 1937 in response to a leading article in the TLS, it was most interesting that Kierkegaard, sceptical about the power of history lessons, looked instead to “some poet of the future” to secure his own reputation – to recognize his “gesture against the masses” and his place “among those who have suffered for an idea”.

On the one hand, Riding remarks, “Such an appeal to the authority of poets is so rare that one would love Kierkegaard if one could”. But for deeper reasons, she couldn’t: his philosophy is based on “the insanity of egoism”, and his “spiritual intelligence” is only proof of the “furious energy of his egoism” rather than “spiritual greatness”. “So at least it seems to me as a poet. For me a forbidding shadow of evils hangs over his work . . . .”

It’s not a response that will be widely echoed, I suspect, around the world during the commemorative events to come. But it could perhaps be considered revenge for Kierkegaard’s characteristically unhappy description of a poet:

“A poet is an unhappy being whose heart is torn by secret sufferings, but whose lips are so strangely formed that when the sighs and the cries escape them, they sound like beautiful music . . . And men crowd about the poet and say to him: ‘Sing for us soon again’; that is as much as to say, ‘May new sufferings torment your soul . . .’ And the critics come, too, and say: ‘Quite correct . . .’.”

May 3, 2013

Franco-German discord

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Franco-German

relations are, it seems, destined never to be straightforward. What was

supposed to be the highpoint of the events celebrating the 50th

anniversary of the Elysée Treaty, or Friendship Treaty between France and

Germany, signed by Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, has generated

controversy of the kind I imagine both parties would rather have avoided.

The

exhibition at the Louvre, De l’Allemagne, 1800-1939: German thought and

painting, from Friedrich to Beckmann, brings together more than 200 works, most

never before exhibited in France. The venue could not be more

prestigious, the project was jointly conceived by the museum and the German

Center for the History of Art in Paris. The title De l’Allemagne alludes to Mme

de Staël’s work of that name, copies of which were seized and destroyed by

Napoleon’s police in 1810.

But the

exhibition seems to have met with displeasure in some quarters in Germany, most

prominently in Die Zeit, where the columnist Adam Soboczynski, while conceding that

it’s a fine display “as long as one concentrates exclusively on the selection

of wonderfully contradictory paintings”, draws attention to what he sees as a

teleological interpretation of German art that links its cult of Romanticism in

art to the barbarities of the twentieth century. The piece was provocatively headed

“Auf dem Sonderweg”, a reference to the theory that German history in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took a “special path” that paved

the way for the rise of Hitler. (The Frankfurter Allgemeine

Zeitung also talked of the Sonderweg.) Soboczynski goes on to say that “to call

the [exhibition’s] concept over-simplistic would be an euphemism”. The apparent

references to “pulsions primitives” certainly sound unfortunate. According to

Soboczynski, an unequal struggle is posited between Apollonian and Dionysian

impulses; he also raises suspicions about the cut-off point: “That the

exhibition should end in 1939 (although in the entrance area there are impressive

new works by Anselm Kiefer) is hardly open to misunderstanding. Horror is historically

and philosophically inscribed in German art since the time of Goethe. The

nostalgic landscapes of Italy and Greece, the contemplation of the Gothic, the German

enthusiasm for the Middle Ages, . . . are all, in the interpretation we are

offered, mere stages that lead to the German catastrophe”.

Soboczynski secured

an interview with the director of the German Center for the History of Art in

Paris, Andreas Beyer, who claimed, angrily, to have been excluded from the

curatorial process, a decision he found “highly irregular”, although he

acknowledged that the Louvre would be the main player in the project. Bizarrely,

Soboczynski suggests that a sense of economic inferiority may have provoked what

he saw as an intention to put a contentious interpretation on the art.

The German

ambassador in Paris, no less, Suzanne Wasum-Rainer, felt obliged to reject the

criticisms. In Le Monde she is quoted as saying: “The Louvre is staging the

most important exhibition of German art ever seen in France . . . . To suggest

that [it] intended, in the context of a European crisis, to bring out the

‘particular path’ which led Germany to the politics of national-socialist

extermination is to misrepresent the goodwill, erudition and engagement of the

people involved in this project”. Elsewhere, an article by Bernhard Schulz in

Der Tagesspiegel also rejected his fellow countrymen’s criticisms, and praised the

exhibition – “Seldom has interest in German art and culture been as great as it

is today”.

Le Monde’s

excellent art critic Philippe Dagen reviewed De l’Allemagne under the heading

“Who said there was no such thing as German painting?” – an allusion to a

commonly held French view (much as the Germans long thought of England as

“das Land ohne Musik”), up until quite recently. It was a long and appreciative

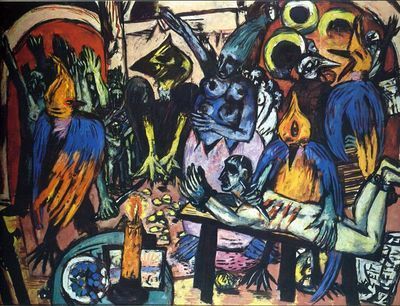

piece, which concluded by saying that the last work in the exhibition, Max

Beckmann’s “The Hell of Birds” (1938, below), is “perhaps the only painting from the

last century that could be hung opposite ‘Guernica’ and hold its own”.

Dagen and Le

Monde’s Berlin correspondent Frédéric Lemaître have since published an eloquent

rebuttal of the criticisms, coming to the defence of the Louvre, whose director

Henri Loyrette expressed himself “surprised and profoundly saddened” by the

comments. Dagen and Lemaître deal with the widely made observation that

movements such as Blaue Reiter and Bauhaus are excluded from the exhibition by

pointing out that they were broadly international in their personnel even if

they had a German origin. And, as the Louvre tactfully chose not to mention in

its defence, the Bauhaus was shut down by the Nazis in 1933 and its leading

lights went into exile. They also point out that Die Zeit has rowed back,

publishing a long article by Michel Crépu in which he claims this is perhaps

the first time that Paris has embraced the history of German art in all its

complexity.

More recently

Le Monde ran a piece in its books section by Nicolas Weill about a proposed

museum of Romanticism in Frankfurt. The article was headed “Les Allemands et

leur romantisme embarrassant”. In it, Weill approvingly cites a book by the

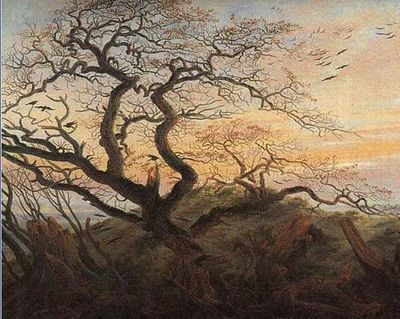

German historian Rüdiger Safranski, Romantik: Eine deutsche Affäre, which

dismisses any idea of a direct link between German Romanticism and Nazism:

“Nazi ideology was leagues away from the elitist individualism which

characterizes so many of the outstanding figures of German Romanticism and the Führerprinzip had little in common with the contemplative passivity that

suffuses the atmosphere and semi-dreamlike landscapes of the painter Caspar David

Friedrich (1774–1840)", whose "Tree of Crows" from the exhibition is below.

I have to

confess that I haven’t seen De l’Allemagne and don’t think I’ll have the chance

to see it – much as I’d like to (it’s on until June 24). I did, however, see a

wonderful Friedrich exhibition at the Centre Culturel du Marais in Paris in

1984. The curators had the clever idea of playing the Prelude to Wagner’s

Parsifal on a loop, as each room in the intimate gallery opened up onto another

spectacular landscape. It was my introduction to Friedrich as well as to the

music of Wagner, and they complemented each other thrillingly.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers