Peter Stothard's Blog, page 66

February 20, 2013

History's master narratives

Considering how low down on the academic agenda history tends to be in our schools (well behind English and Mathematics, and these days a poor relation too of Science and ICT), it perhaps should surprise us more than it does how much of a fuss is made of proposed changes to the National History Curriculum. Earlier this month, the Secretary of State for Education, Michael Gove, published his consultation document on the whole National Curriculum, and although there has been some discussion of various parts of it (Sir James Dyson, the knight errant of vacuum cleaning and inventor of that savage hand drier, didn't much like the prospects for Design and Technology), it is History that has twisted the most knickers. Perhaps that's because, encouragingly, we all feel we have a continuing stake in history, whereas other areas of the National Curriculum tend to devolve, after we leave school, to others' specialisations.

The objections to the new proposals centre on the idea that the picture presented is a barely updated version of Our Island Story, or 1066 and All That played straight. Critics have included trustworthy historians (and contributors to the TLS, which I hope is the same thing) such as Peter Mandler and Richard Evans, while another TLS stalwart, Niall Ferguson, has defended the outlines. When you look at what is proposed, however, it is hard to avoid the sense that this is a set of ideas taken from the backs of a lot of envelopes. The overall vision of the current curriculum, to allow children to "investigate Britain's relationships with the wider world", while finding out in turn about "the history of their community, Britain, Europe and the world", has been replaced by the altogether more Gradgrindian prospect of being "equipped", to "think critically, weigh evidence, sift arguments and develop perspective and judgement". Of course, one hopes that history teaching would result in both, but the rather chilly initial position doesn't leave much room for the prospect that it might be a bit of a thrill to learn about the past too.

But it is the outline itself that reads like someone wrote down a DfE brainstorming session. How do you do history? Well, from the Year Dot to the Present Day, of course. And by history, we mean us. So pupils will (apparently) start with the Stone Age, and move on through Celts (who they?), Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Plantagenets and so on. The periods are broken down into headings, such as Heptarchy under Anglo-Saxons, a concept that bears little relation to reality and smacks of a view of English history that is Georgian at the latest. Other interpolations are similarly arbitrary. When it comes to "the later Middle Ages and the early modern period", there is Caxton and the Wars of the Roses -- and Warwick the Kingmaker, which, again, is not a name by which Richard Neville was actually ever known, and which hints, again, at the idea that this is a document drawn up by people who don't actually teach or read history today, but remember a bit about it.

There's nothing at all wrong with learning about the indviduals the document names, merely that it immediately makes you think of all the individuals it doesn't. Why Christina Rossetti under "creative geniuses"? Is she really a more important poet than Keats or Shelley? What merits more of a challenge, however, is the assumption that this is the way to do it. Start kids off with the Stone Age, and take them step by step up to the present day. Why? Are eight-year-olds peculiarly attuned to the world view of Stone Age man? Do nine-year-olds have a natural affinity for the Anglo-Saxons (you would have thought the difficult spellings alone might be enough to put some off)?

I take the point that picking and choosing periods can result in a very fractured view of history -- Victorians one term, Ancient Egyptians the next -- but might it be worth doing both? That is, children could learn about the broad outlines of British (and world) history in a year, perhaps in the middle of primary school, and then teachers could have some choice about which bits to focus on next. And while it's important to learn about the country you live in, the idea that you should learn about the Stone Age only from its intersection with Britain (among "early Britons and settlers") seems almost wilfully insular.

What all this ignores, however, is how much relation it bears to reality in classrooms. In primary schools, history is often lumped in with other "topics" -- science, religion, geography -- to be covered in the interstices of the blanket focus on the endless tested Maths and Literacy. No wonder it is reduced to a dab of empathy and never mind the facts, and secondary school history has to start all over again. Even then, to judge by one disgruntled history teacher's account, the learning remains "play-centred", and lofty pronouncements from the top won't change that unless teachers are on board too. Children deserve to be offered something a bit better considered, both in terms of the proposed curriculum, and the time allocated to teach it.

February 14, 2013

The raw art of Jean Dubuffet

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“Without bread, we die of hunger, but without art we die of boredom.” So wrote the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-85).

But maybe boredom isn’t such a bad thing. Elsewhere he says, “I think it is very healthy for an artist to be bored. Boredom is the rich compost that fertilises the creation of art”.

Dubuffet invented the concept of Art Brut, or raw art: “A work of art is only of interest . . . when it is an immediate and direct projection of what is happening in the depths of a person’s being . . . only in this Art Brut can we find the natural and normal processes of artistic creation in their pure and elementary state”.

Taking care of the family wine business, Dubuffet didn’t begin his career as an artist until he was 41, although he had enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Le Havre when he was 17. He claimed to take “hardly any interest in the work of other painters . . . . I don’t like culture; I don’t like the memory of the past . . . . I believe in the great value of forgetting”.

A recent exhibition, “Transitions”, of a dozen or so of Dubuffet’s works at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester was a reminder of his enduring originality. It was the “first major review of Dubuffet’s work in a public museum in the UK for nearly 50 years”. The first, in 1955, was curated by Roland Penrose (husband of Lee Miller and friend of Picasso). This was followed by retrospectives at the ICA and Tate in 1966.

The Pallant House exhibition focused mainly on his “L’Hourloupe” series, made up of white, red and blue shapes with thick black borders, which he composed between 1962 and 1974. The word, coined by Dubuffet, derives from “hurler” to shout, “hululer” to howl and “loup” wolf. He applied the concept to objects, such as “Teacup VII” (below) or figures, like the extraordinary polyurethane and latex sculpture of a gendarme. In a felicitous phrase Dubuffet likened the works to a “festival of the mind”.

Dubuffet was something of a writer’s artist (and was a prolific writer himself: there are four volumes of Écrits). Raymond Queneau, Francis Ponge and Claude Simon all wrote enthusiastically about him; he visited poor mad Antonin Artaud in his asylum in Rodez, and arranged for his discharge in 1946. Meanwhile he found it hard to forgive his friend Jean Paulhan for joining the establishment by becoming a member of the Académie française.

Championed by the American art critic Clement Greenberg, Dubuffet had, for a while a bigger reputation in the US than in France. Now there is a Fondation Dubuffet in Paris, and a collection of Art Brut in Lausanne.

In their Jean Dubuffet: Works, writings and interviews, Valérie da Costa and Fabrice Hergott called him “one of the most surprising artists of the twentieth century”. They describe him as an “anarchist, atheist, anti-militarist, anti-patriotic”. (The text has been quirkily translated: “a reasoned catalogue” is presumably a catalogue raisonné.)

Dubuffet himself liked to call his portraits “anti-psychological”; maybe da Costa and Hergott are stretching it a bit when they see in the portrait of the austere Ponge (1947, below) an “exceptionally good likeness”. And there was nothing anti-patriotic in the blaze of red white and blue that greeted the visitor to the main room of the Pallant display, with the Hourloupe in all its playful glory.

February 12, 2013

The German Shepherd bows out

Pope Benedict XVI © Tony Gentile/Reuters

BY RUPERT SHORTT

To many, the news was seismic. No pope has resigned since the fifteenth century. Perhaps, though, the portents of Benedict XVI’s abdication were there all along. Two years ago he told a German interviewer, Peter Seewald, that a pope could step down if he were too physically or mentally frail to do his job. Even John Paul II, renowned for the doggedness with which he pursued his ministry in the face of chronic ill health, is said to have entrusted his private secretary with a resignation letter to be published if he reached a certain level of incapacity.

But John Paul’s mental condition see-sawed. His toughness won the admiration of many; overall, though, the effect on the Church was very mixed. The barque of Peter was steered this way and that by competing Vatican officials, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger among them. The contrast between sclerosis at the top, and the vibrant grassroots of the Church in Latin America, Africa and Asia, looked stark.

It was perhaps concern over the prospect of further drift that fed Benedict’s wish to spend the final months or years of his life out of the spotlight. He has set a good precedent: Paul VI, in office from 1963 to 1978, wanted to retire, but clung on to office in a state of increasing decrepitude out of a sense of duty. Pius XII, a victim of quacks, was corpse-like long before his death in 1958.

Even so, there are many who question whether the latest news augurs well for the Church. In the first place, a new pope may feel hedged in by a living predecessor. Others suggest that the next pontiff will almost certainly be Benedict’s man, because the College of Cardinals is packed with conservative clones and weighted in a European direction. The chief criticism targeted at Joseph Ratzinger for over 30 years has been that he acted as a player, promoting his own hardline interpretation of the faith, when he should have been a referee and bridge-builder. Debate about reform – on church government and financial transparency, let alone over teaching on the place of women or clerical celibacy or sexual ethics – is thus likely to be put on ice.

But the future is far from certain. John XXIII, an elderly man elected as a caretaker leader in 1958, turned the ecclesiastical world upside down by summoning the Second Vatican Council. The lesson? Elective monarchy is the most unpredictable form of rule yet devised.

Žižek mania

By TOBY LICHTIG

Which contemporary intellectual generates more words than any other? It's an impossible question, and perhaps a foolish one, but sifting through the sacks of books that arrive daily at the TLS, one is tempted to come up with a definite answer: Slavoj Žižek.

The Slovenian philosopher, critic, essayist, journalist and Lacanian-Hegelian-Marxist theorist has an apparently infectious habit of generating streams of noun-heavy theorizing about subjects as diverse as religion, food, violence, psychoanalysis, media, terrorism, fashion, geopolitical upheaval, Lacanian-Hegelian-Marxist theory and Kung Fu Panda; and the more he writes, the more, inevitably, he gets written about.

In the past two years alone, along with countless reviews and essays, Žižek has published The Year of Dreaming Dangerously; Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the shadow of dialectical materialism; God in Pain: Inversions of apocalypse (with Boris Gunjević); and Hegel and the Infinite: Religion, politics, and dialectic (with Clayton Crockett and Creston Davis); while recent books about the man include Žižek: A guide for the perplexed (2012) by Sean Sheehan; The Symbolic, The Sublime, and Slavoj Žižek's Theory of Film (2012) by Matthew Flisfeder; Žižek and Communist Strategy (2012) by Chris McMillan; and Žižek Now: Current perspectives in Žižek studies (2012), edited by Jamil Khader and Molly Anne Rotherberg.

There is an International Journal of Žižek Studies and a Centre for Ideology Critique and Žižek Studies (at Cardiff University), not to mention innumerable conferences and seminars. Žižek is the subject of various documentaries, including Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! (1996) and Žižek! (2005), and he has starred in a slew of films including Sophie Fiennes's The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (2006) and The Pervert's Guide to Ideology (2012), and Jason Barker's Marx Reloaded (2011). As if to underline his multidisciplinary approach, the Royal Opera House has recently commissioned a series of works inspired by Žižek's writings.

Now there is, of course, nothing wrong with being prolific and popular, and there is a huge amount to be admired about the diverse and provocative corpus of Slavok Žižek the thinker. But there are times when, it seems, Žižek mania transcends scholarship and spills over into outright hero worship. This impression is partially upheld by the hyperbolic praise he tends to generate in the media. Žižek is described as, for instance, "the world's hippest philosopher" or "the Elvis of cultural theory", even if he himself refutes such claims. And what is even more remarkable about the Žižek craze is that, despite his pop star status and apparently mass appeal, the sort of writing he inspires tends towards quite the opposite of pop clarity and brevity. Take this single-sentence excerpt from Žižek Now, drawn more or less at random:

Contemporary post-political societies are marked not only by an allegedly successful overcoming of earlier forms of "totalitarian" universal politics in the name of "peaceful" and pragmatic deliberations aiming at consensus, but also by the more or less implicit ideological conviction that violence presents no longer an eminently political problem; that is, violence today appears paradoxically as disavowed violence both in the quasi-naturalist form of the objective-anonymous machine of market forces simply taking its course and in ubiquitous spurious claims as to the final realization of an allegedly multi-cultural and even postcolonial coexistence of different cultures and ethnicities, or, on the other hand, as "excessive" and "irrational" violent eruptions, supposedly unrelated to the current socioeconomic order and the persistence of neo-colonialist structures of subjugation and exclusion, to be dealt with by decreeing different kinds of statist police actions.

Did you get all that?

It's not that it doesn't make sense, because it sort of does, in its own inelegant way. But my concern is that writing such as this carries with it a wearisome sense of cultural theory by numbers, of regurgitation rather than interrogation; and one is sometimes tempted to wonder where the Žižek mania is leading us. The philosopher himself remains ambiguous about his followers and fame (as he is about so much else) and has claimed to "despise public appearances" and never to have read the International Journal of Žižek Studies.

I wonder what would happen if we, collectively, gave Žižek a rest for a few months. Could we cope with the silence? Are we up to the challenge? Just a thought.

February 6, 2013

Digging for Richard

© University of Leicester

BY DAVID HORSPOOL

Our reviewer Alex Burghart quoted his old history tutor in the TLS not long ago: "Archaeologists", this sage opined, "are a pain in the arse. They think they know better than the texts and they will find things." As Burghart went on to say, "If the first point is unfair, the second is undeniably true." Monday's events in Leicester brought these words to mind. But if we grant that, sensible scepticism aside (and see Mary Beard's blog), the bones in the social services car park are those of Richard III, does that "change the history books", as we have repeatedly been told? This week in the TLS, Sarah Knight and Mary Ann Lund of the University of Leicester trace literary and historical accounts of the King's deformity from the chronicler John Rous onwards.

What Richard might have looked like is naturally of interest, and if accounts of his physical appearance match chroniclers' descriptions, that could make other aspects of those accounts more credible. Carbon dating and DNA evidence may not be quite as cut and dried as some would like, but that's nothing compared to literary historical evidence. Amid the excitement about the Leicester discovery, some party poopers have wondered whether the University's media management was not as important a part of the story as the discovery itself. But if the archaeologists and scientists are above criticism for their scrupulous approach to their "one in a million" find, the historical material published on the University website associated with the dig falls rather below those standards.

The partners of the University in this dig are the Richard III society, whose specific purpose is the rehabilitation of the reputation of the King. So when the University site tells you of the Princes in the Tower that "Young Edward and his brother moved into the Tower of London (which was then a royal palace, not a prison) but in June their parents’ marriage was declared invalid", it's worth pointing out that, actually, the Tower had been used as a prison for many years (William the Conqueror's eldest son was imprisoned there in 1106, for example), and the fact that the marriage was declared invalid was almost certainly part of an orchestrated campaign conducted by Richard to clear his path to the throne.

"Ricardians", as the King's advocates are known, may feel their man will get a better press from now on, despite (or because of?) the fact that, contrary to their previously widely held theories, Richard does indeed seem to have sufferred from a spinal deformity. But the emotions surrounding this extraordinary discovery shouldn't have any influence on what we think Richard did, or how he lived.

February 5, 2013

The angels of translation

by Thea Lenarduzzi

In Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, by the Romanian born author

Aglaja Veteranyi, there is a passage in which a child wonders: “Are there

angels translating for God? Or can God understand all the foreigners?”.

Vincent Kling's funny

and engaging reading from his translation of the novel, delivered to a packed

auditorium at King's Place, N1, last night, came as part of this year's

Translation Prizes ceremony, at which he took the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for

translation from German (for a full round-up of the winners and runners-up, see

Adrian Tahourdin's piece). Leaving to one side the question of polyglot angels,

it became possible last night to distil from the act of translation a certain

angelic quality – whether consciously undertaken as such, or coming as a welcome side-effect.

To attempt to promote

dialogue across the gap is no small undertaking, especially when, as Avi Sharon admitted of

the Selected Poems of C. P. Cavafy,

“it is hard to justify another translation of Cavafy”. And yet, on returning to

his seat after reading from that very thing, Sharon was congratulated by Malcolm

Imrie, another of this year’s

winners, who whispered his appreciation:

“that was beautiful”, and it was. An especially pertinent example of Cavafy's

gentle, persuasive repetitions were conveyed in “Ithaca”, in which the speaker

urges us to undertake a journey “long, / rich in adventure, rich in discovery”

to that emblematic Ionian island: “Then sail to Egypt's many towns / to learn

and learn from their scholars”.

Malcolm Imrie's own

prize-winning translation of La Peur, Gabriel

Chevallier's novel about the First World War is a shining example of the role

that translation might play in encouraging discussion, understanding and,

perhaps, a sense of community. “This”, he explained, “is a good novel for these

fearful times ... in Europe, where there's another kind of war going on.”

Following the

prize-giving, Boris Akunin took to the stage to deliver the 2012 Sebald Lecture

(previous speakers include Susan Sontag, Seamus Heaney, Carlos Fuentes and,

last year, Sean O'Brien). Akunin, who translated Japanese literature into Russian before becoming a successful novelist in his own right, enriched our

image of a celestial fleet of polyglots, with an amusing, tongue-in-cheek

account of his fall from translator to crime-fiction novelist. In his speech,

entitled “Paradise Lost: Confessions of an apostate translator”, Akunin

described how his mother bid him as a child to choose one of the only two “clean”

professions in the USSR – medicine, or literary translation. (His poor

scientific aptitude made it less of a choice….) An early indication of his

piousness came in his translating of a Rafaele Sabatini novel as a gift to a

less linguistically dextrous friend, and brings to mind another bit from

Vincent Kling’s reading in which the child protagonist – an illiterate and

unschooled “gypsy” – explains how, “in my sea, you don’t have to be able to

swim to go swimming”. Translators in the audience could bob their heads

knowingly.

When Akunin embarked on

his career as a literary translator, he became part of a group of literary

elites who could get into the swankiest parties. Translators were revered: the

cleanest of the clean, they dealt in the “pure” literature of the Greats and

did not dirty their hands with politically engaged – at least not expressly so

– literature. (Pasternak earned his bread and butter translating Shakespeare,

while writing Doctor Zhivago in secret.) Their role was merely to

relay – they were Puskin’s “post-horses of the Enlightenment”. But after translating exclusively scientific

articles and technical manuals, Akunin began to sully himself in riskier

endeavours. Mishima’s books – “hymns”, to perversion, to destruction, to

suicide – were ripe for translation. From him he learnt that nuances were more

important than ideas, shade more than light.

And yet Akunin tired of

the task. He found himself becoming frustrated with these writers and their

long, scene-setting descriptive passages. “It was rainy. The sky was grey” – why not just get to the point, he asked? He didn't have the infinite

reserves of patience, he admitted, required to keep his seat alongside the celestial ones. He

moved to the dark side and began writing “middle-of-the-road” detective stories

which, though not immediately successful, became the favoured reading material

of the now burgeoning Russian middle classes. In 2000 he was nominated for the

Smirnoff-Booker Prize, and was named Russian Writer

of the Year.

In Russia today, he said, “nobody

wants to hear about my translations” (which, to return to my point about

intercultural understanding, is politically insightful, if nothing else). And yet, Akunin concluded, “my mother never

approved of my metamorphosis” . She read his novels with a pencil and

questioned his plots – why not do something “serious”, “why not translate something?”, she pleaded. The

warm applause that followed Akunin’s lecture suggests that many of us present

last night would side with his mother and welcome a defection.

January 31, 2013

The present and future of literary journals

What state are literary journals in? How are they changing? Those questions were at the heart of a discussion led by the editors of the White Review, Jacques Testard and Benjamin Eastham, at the launch of Issue Six at Foyles bookshop last week.

Christian Lorentzen, an editor at the London Review of Books and the editor of the n+1 anthology, was quick to remark on how many more literary magazines there were in the US: “They’re even at war with each other . . . . [As a writer] you can go from one to the other, trying things out”. It was with that fact in mind that the White Review was founded: its editors told Bookforum last year that

“In lit-mag terms, the literary scene in New York is infinitely more happening than London's. There are so many great magazines, many of which are youngish, that would have made the White Review almost pointless had they existed in London. We’re thinking of n+1, Guernica, Cabinet, the Paris Review, Bomb, Bookforum. In London, Granta is close to us only in that it publishes fiction and reportage, although they work with more established writers”. (See an interesting article about US literary magazines here.)

It follows that when Rachael Allen co-founded Clinic – a poetry, arts and music collective – in South London in 2009, in her late teens, the idea was to fill a gap: “We just found that a lot of the poems and poets we were reading weren’t being read by our peers . . . .We don’t have a game plan – we wanted to promote poets we were reading and were involved with. Then other editors and poets started to notice what we were doing”.

Testard and Eastham originally thought they could get by without a website, but soon learnt that that wasn't possible. Ellah Allfrey, deputy editor of Granta, agreed that “you have to invest in it”; Granta publishes one story from each print version online, plus lots of teasers, and commissions extra material especially for the website. “We don’t publish political pieces in print, but we can respond in a writerly way online.” The free content encourages submissions from those places where print subscriptions are not available.

As Lorentzen pointed out, the internet fosters a different kind of writing. “A polemical piece with an argument right at the top – that’s going to be a hit, even if it’s not a great piece of writing." (That’s not to say that more considered pieces won’t be passed around in the same way – he described “Alien vs Predator" by Michael Robbins as “the most viral poem in the history of the internet”.) He has observed a tendency for writing techniques acquired for the internet to “seep into print”. “The internet offers great possibilities. But we shouldn’t lose our commitment to paper.”

All three editors have experienced the exhilaration of discovering talented new writers. Lorentzen reads the slush pile every day (he was obsessive about this when he worked at Harper's Magazine, he said – he would find not only talented unknowns but, occasionally, famous writers – including Ray Bradbury and John Updike – who had ended up there because they didn’t know the relevant editor’s name). At Granta, it used to be interns who sifted through the slush pile; nowadays it’s senior editors. A lot of it is “unreadable”, Allfrey said, but she only needs to look at a letter written by Kazuo Ishiguro to be reminded of its value.

Granta hosts many more events than it used to; “it’s part of an essential growth”, said Allfrey. “It’s organic.” But “in the end, it’s the words on the page that really matter”. Allen and Lorentzen echoed this. For writers, “Knowing where you want to place your work is the really important thing”, said Allen. “I think you can just stick to using a typewriter and postage stamps”, said Lorentzen.

Below: A poem by Emily Berry from Clinic III, to be published in March.

Top: Illustration by Jack Hudson, from Clinic II

January 29, 2013

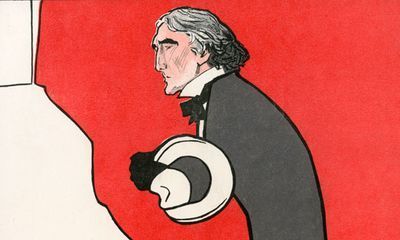

Stoker, the stage and the London Library

By MICHAEL CAINES

"To be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS." That's what I promised on this blog back in November, at the end of a piece about Bram Stoker, Wilkie Collins and the theatre. Now Tracy C. Davis's fascinating piece on the book I was talking about, Bram Stoker and the Stage, is not only in the paper but on the TLS website, as Bram Stoker before Dracula. It's quite a story.

That's Stoker's sometime boss Henry Irving depicted in the illustration above (from The Critic, 1899, by Frank Chesworth, who also produced striking caricatures of other theatrical luminaries, such as Sir Arthur Sullivan and Charles Wyndham). It has been said that the "lanky, weirdly locomoting, charismatic Irving" provided Stoker, his business manager, with an obvious source of inspiration for his vampire. But does it follow that Irving himself exercised a "vampire-like" power over Stoker in real life, and "drained his creative vitality"?

The editor of Bram Stoker and the Stage isn't so sure. And Tracy Davis suggests that there are more basic questions to be answered about Stoker that are overlooked by critics scouring the biographical vaults for signs of vampiric life (if that's not a contradiction in terms).

As a postscript, however, and, I think, a further example of Professor Davis's point: between my promise of a review and the review itself, came this piece from the London Library's blog, which naturally I've only just got round to reading. There are even a few things to be learned from old library membership forms, it turns out.

January 24, 2013

A ringside seat

By DAVID HORSPOOL

What does this picture make you think of?

[image error]

To a prosaically-minded sport editor at the TLS, it is one of Neil Leifer's classic shots of Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston, on May 25, 1965, when Ali defeated the former heavyweight champion Liston for the second time, knocking him down in the first round with what, according to taste, became known as the "phantom", or the "anchor" punch. According to the rules of boxing, Ali shouldn't have been in that position, and Leifer shouldn't have been able to get his shot, or the even more famous one in which his right hand is curled, ready to do more damage – an image that has been called the greatest sports photograph of all time. The champ should have retired to a neutral corner to let the referee, Jersey Joe Walcott (himself a former heavyweight champion) begin the count. In fact, the contest can be classified as the only sporting world championship ever decided by an editor. In this case, Nat Fleischer, Editor of Ring Magazine, who pointed out to the ref (wrongly, it might be argued), that "the fight's over" as pandemonium reigned. Such was the respect accorded Fleischer, Walcott stopped the bout: that's what I call editorial interference.

When I saw a book with this picture on the dustjacket in our offices, I naturally made a grab for it, while wondering "can there be any more to say about Ali?" Well, there may be, but not in this book, the title of which is The Iliad, by someone called Homer, who seems to have been trained, or "translated", as the publishers put it, by a professor based in Rhode Island, Edward McCrorie. Apart from its unusual choice of cover image, the book seems to be in every other respect a straightforward new version of the epic poem. So where does Ali fit in? (And why, by the way, in the caption on the cover, is he described as "Cassius Clay, later Muhammad Ali", when he had already announced his conversion to Islam by the time of the second Liston fight?)

Unless I've missed it, the editorial matter and translator's preface offer no answer. Ali, of course, was something of an oral poet himself. Could it be that "Big Ugly Bear", "The Gorilla", "The Mummy", "The Rabbit" (Ali's nicknames for Liston, Joe Frazier, George Foreman and Floyd Patterson – though my favourite is the one he gave Ernie Terrell: "The Octopus") are the modern equivalent of Homer's epithets, "Odysseus of the many wiles", or "swift-footed Achilles"? Perhaps, but maybe the idea this particular picture is meant to promote is a reminder that all fighting involves boasting and naked aggression, even if the people who do it look beautiful, and the boxers, at least, aren't necessarily inviting death.

The Homeric moment this image most brings to mind for me is when Hector stands over Patroclus as the Achaean lies dying at his hands. "Lie there, Patroclus! and with thee, the joy / Thy pride once promis'd of subverting Troy", as Pope translated it; in Christopher Logue's War Music version: "Why tears, Patroclus? / Did you hope to melt Troy down?"; Edward McCrorie goes for: "Patroklos, likely you claimed you'd plunder our city". According to the best accounts from ringside in 1965, Ali said "Get up and fight you bum! You're supposed to be so bad!"

The book will be passed from the sports to the Classics editor for a more informed assessment.

January 21, 2013

Books to beat the gloom

Today

is "Blue Monday", the "most depressing day of the year", a

perfect storm of mid-winter drudgery, post-Christmas comedown and credit card

overload. Or is it? This entirely spurious "equation" was actually

devised for a travel firm to help sell holidays in the sun, but it's the sort

of ritualized non-story that runs well in certain sections of the media, and as

you read this blog, the web is awash with comment pieces and interviews featuring concerned

psychologists explaining why the third Monday in January is a day for hiding

beneath the duvet.

At the TLS we are, however, of an altogether more cheerful disposition, which is why our thoughts turn to the uplifting matter of this year's forthcoming fiction titles. (And if you are cowering beneath the duvet, then a good novel can surely only help you.)

Among

the highlights to arrive in Britain over the next month are Dave Eggers's A

Hologram for the King – a tale about America, globalization and the world

economy, set in Saudi Arabia – and Nadeem Aslam's The Blind Man's Garden –

which looks at the effects of war and geopolitical upheaval in contemporary

Afghanistan and Pakistan. Jim Crace's Harvest considers a rather different kind

of political upheaval, moving back three centuries to a Britain torn apart by the new acts of

enclosure.

If

that isn't enough to raise some cheer, then March spells the return of William Gass – now

in his late eighties – with his first novel in almost two decades. Middle C

moves from 1930s Austria to post-war Ohio, and features a piano-playing

fantasist struggling to come to terms with the mysterious disappearance of his

father. Also out in March is Javier Marías's "metaphysical murder mystery" The Infatuations (published

last year in Spain as Los enamoramientos), in which a woman becomes embroiled

in the fall-out of an apparently random killing. Marías is joined by J. M. Coetzee, whose novel The

Childhood of Jesus will already have bookies speculating (regardless of their

having read it) on the possibility of the author winning a record-breaking

third Booker Prize.

In

April, we will be treated to new novels by Kate Atkinson and Rupert Thomson.

Atkinson's Life after Life features a woman who is given the chance to overcome

death – again and again. Thomson's Secrecy follows a man being pursued by his

past in Renaissance Florence, Naples and Sicily. (Renaissance Italy is also the

time and place for Sarah Dunant’s Blood and Beauty, which appears later in the

year.)

In

the same month, Granta’s "Best of Young British Novelists" circus

swings around again, while a young British novelist (and TLS reviewer) who may

or may not be on the Granta list arrives with his debut, Idiopathy: Sam Byers's

novel is billed as a tale of "tangled relationships", "unhinged

narcissism" and "self-help quackery".

As

the days begin to lengthen, we can look forward to new novels, in May, by John Le Carré (A Delicate Truth), Lionel Shriver (Big Brother) and James Salter (All That Is). Summer solstice arrives just

in time for The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman and the final

instalment of Jane Gardam’s “Old Filth” trilogy, Last Friends; in August,

Margaret Atwood unveils the final instalment of her trilogy, MaddAddam. By

September, it will be back to school with Jonathan Coe (Expo 58) and Iain Pears, whose novel, Arcadia, will first appear as an app.

But those

days of long shadows are far off in the distance, and for now we must now

embrace – or shrink from – the winter gloom. Whether you're feeling morose or

optimistic, we hope you'll enjoy reading more about these novels, all of which

will be reviewed in future editions of the TLS.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers