Peter Stothard's Blog, page 67

January 19, 2013

Margaret Atwood on Wattpad

By CATHARINE MORRIS

This week, The Times ran an article about Beth Reeks, who has secured a three-book deal at the age of

seventeen. The article mentioned that she had built up a readership via

Wattpad, a free online novel-sharing platform for amateur writers that

“Margaret Atwood has hailed as the future of the form”.

If only Atwood had had access to it when she was a teenager: at a recent RSL event in Canada House in Trafalgar Square, she told us that her

first step in becoming a writer was buying a publication called Writers’

Markets, which said that the money was in true romance stories. She told us: “I

thought, I‘ll do that during the day and write my deathless masterpieces at

night”. There was a certain formula to these stories, she said. “There would

be a choice between two men – one would have a motorcycle and one would work in

a shoe store. The woman would get involved with the unreliable one . . . . There

were various ways of ending the story. The best way was patching things up with

the shoe store guy . . . . But there would always be a scene on the sofa: ‘and

then they were one’. I couldn’t bring myself to do that. That wasn’t going to

happen.”

Her next idea was journalism school. Her parents, “biting

their tongues”, “dredged up” a journalist second cousin, who told her that, as

a woman, she would end up doing “nothing but obituaries and the ladies’ fashion

pages”. She decided to go to university and write in the summer

holidays. At the time she graduated, teachers were in great demand, so she

taught grammar to engineers at the University of British Columbia. “At 8.30 in

the morning. They were asleep. I was also asleep.”

Becoming a professional writer in Canada wasn’t easy for

anyone. Atwood told us that in the 1950s and 1960s there were only about five literary

magazines. In 1960, only five novels by Canadians were published in Canada. In

bookshops, Canadian poetry and fiction would appear in the “Canadiana” section.

Many aspiring writers left for England or the US. One important champion of

Canadian literature was Robert Weaver, who helped to establish the reputations

of a number of now well-known writers via his Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

radio show. “He paid you. He paid money – it was a big thing”. Gradually, “a space was made”. Still, Atwood “never expected to make any

money. Even the magazine market was drying up” – but she was eventually able to

start writing full-time in 1972.

Atwood might not need Wattpad now, but she does have a page

on it; and she has shared two works

there – Speeches For Doctor Frankenstein, a poem cycle originally printed in

1966 in an edition of fifteen copies illustrated by her friend Charles

Pachter; and "Thriller Suite", a new collection of poems “inspired by

her long history as a reader of strange tales, from 19th century gothic

classics to ghost stories to crime fiction and thrillers”. She has also shared

a link to The Happy Zombie Sunrise Home, a serialized novel written with Naomi

Alderman. But her presence has more to do with other people's work than her

own. When she joined the site in June she said to one journalist:

“How do young people get their practice in? We did it

through the high school magazine, but it was an embarrassing thing because your

real name was on it. On Wattpad you can put your real name or have a pseudonym,

which a huge number do. Then you can get out there, get feedback, but not have that horrible expectation of people

jeering at school. It's actually a pretty pure way of getting a readership

that's not going to look at anything but your writing”.

Atwood's new

novel MaddAddam will be reviewed in a

future issue of the TLS.

Photograph by George Whiteside

(writing under the name Beth Reekles) has secured a three-book deal at

the age of seventeen. The article mentioned that she had built up a

readership via Wattpad, a free online novel-sharing platform for

amateur writers that “Margaret Atwood has hailed as the future of the

form”.

If only Atwood had had access to it when she was a teenager: at a

recent RSL event in Canada House in Trafalgar Square, she told us that

her first step in becoming a writer was buying a publication called

Writers’ Markets, which said that the money was in true romance

stories. She told us: “I thought, I‘ll do that during the day and

write my deathless masterpieces at night.’” There was a certain

formula to these stories, she said. “There would be a choice between

two men – one would have a motorcycle and one would work in a shoe

store. The woman would get involved with the unreliable one . . . .

There were various ways of ending the story. The best way was patching

things up with the shoe store guy . . . . But there would always be a

scene on the sofa: ‘and then they were one’. I couldn’t bring myself

to do that. That wasn’t going to happen.”

Her next idea was journalism school. Her parents, “biting their

tongues”, “dredged up” a journalist second cousin, who told her that,

as a woman, she would end up doing “nothing but obituaries and the

ladies’ fashion pages”. She decided to go to university – she studied

English, philosophy and French (there were no creative writing

courses) – and wrote in the summer holidays. At the time she

graduated, teachers were in great demand, so she taught grammar to

engineers at the University of British Columbia. “At 8.30 in the

morning. They were asleep. I was also asleep.”

Becoming a professional writer in Canada wasn’t easy for anyone.

Atwood told us that in the 1950s and 1960s there were only about five

literary magazines. In 1960, only five novels by Canadians were

published in Canada. In bookshops, Canadian poetry and fiction would

appear in the “Canadiana” section. Many aspiring writers left for

England or the US. One important champion of Canadian literature was

Robert Weaver, who helped to establish the reputations of a number of

now well-known writers via his Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio

show. “He paid you. He paid money – it was a big thing”. It was in the

1960s and 70s that “a space was made”. Still, Atwood “never expected

to make any money. Even the magazine market was drying up” -- but she

was eventually able to start writing full-time in 1972.

Atwood might not need Wattpad now, but she does have a page on it

(http://www.wattpad.com/user/MargaretA... and she has shared two

works there -- Speeches For Doctor Frankenstein, a poem cycle

originally printed in the 1960s in an edition of fifteen copies

illustrated by her friend Charles Pachter; and "Thriller Suite", a new

collection of poems "inspired by her long history as a reader of

strange tales, from 19th century gothic classics to ghost stories to

crime fiction and thrillers". She has also shared a link to The Happy

Zombie Sunrise Home, a serialized novel written with Naomi Alderman.

But her presence has more to do with other people's work than her own.

When she joined the site in June she said to one journalist:

"How do young people get their practice in? We did it through the high

school magazine, but it was an embarrassing thing because your real

name was on it. On Wattpad you can put your real name or have a

pseudonym, which a huge number do. Then you can get out there, get

feedback, but not have that horrible expectation of people jeering at

school. It's actually a pretty pure way of getting a readership that's

not going to look at anything but your writing".

January 18, 2013

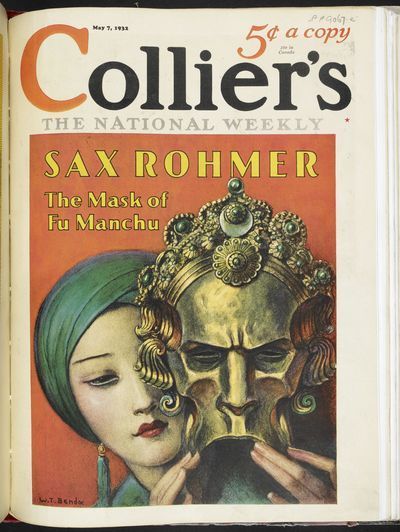

Pelé, Conan Doyle and Fu Manchu

By MICHAEL CAINES

Murder in the Library, a free exhibition in the British Library's open Folio Gallery space, opens today; items on display include, as above, crime novels by unlikely suspects such as the great footballer Pelé (acclaimed on the front cover as the "Dick Francis of the football thriller") and the striptease artiste Gypsy Rose Lee (the strapline reads: "Strangled . . . with their own G strings").

But there are also copies rare and commonplace of Golden Age favourites, nineteenth-century forebears (including a true-crime account by a "Disciple of Edgar Poe"), oddities (a crime jigsaw, a solve-it-yourself collaboration by Dennis Wheatley and the art historian J. G. Links), and some modern descendants of the flawed detectives of old: Dave Robicheaux, Inspector "Endeavour" Morse.

All of this is arranged in an efficient alphabet of A–Z displays: N is for Nordic Noir, O is for Oxford, etc. In this way, any doubters who drift into the gallery, one flight of stairs up from the foyer, are implicitly advised that the genre permits this kind of compendious treatment. There's a slight drawback, in that those subjects that would require a double entry under V – Villains and Victims – get short shrift. And Nordic Noir might be currently enjoying its own Golden Age, but there's more to say about other parts of the world, too. You could run a whole exhibition on Italian detectives alone, I'm told, from Brunetti to Soneri, via Marcus Didius Falco and Montalbano.

One villain who does appear, in dubious taste as ever, is Sax Rohmer's Dr Fu-Manchu: "tall, lean, and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green". Some of Rohmer's books were reissued last year, and you can read what our reviewer, Alison Wood, had to say about them here.

And for aficionados of Sherlock Holmes, there is one glorious glimpse behind the scenes: a neat page from the manuscript of "The Adventure of the Retired Colourman". Note that the young Inspector Mackinnon of Scotland Yard, who cries, towards the bottom of the page, "Pooh! What an awful smell of paint!", will have to toughen up if he's going to last in this job – and that at the end of the story, he takes the credit for Holmes's detective work.

January 14, 2013

No Borders

by Adrian Tahourdin

A thought-provoking exhibition recently opened at the Bristol Museum and

Art Gallery, in partnership with Arnolfini. “No Borders”, featuring a dozen

modern artists from the Middle East, Asia and Africa, “reflects upon the

globalised conditions of the world today and the particular histories and

contexts that inform current art practices”. The show runs until June and is free.

Greeting the viewer in the hall of the gallery are five panoramic

photographs, “Peripheral Stories”, by Hala Elkoussy of the outskirts of Cairo

(all taken before the Arab Spring): waste ground, half-built tower blocks,

electricity pylons, dusty roads - unpeopled. Elkoussy describes her native city

as one that “is changing at a very fast pace” (below).

The Mumbai-born artist Shilpa Gupta’s mesmerizing “In Our Times”

consists of two seesawing old-fashioned-looking microphones mounted on a stand,

one intoning Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s first speech as President of Pakistan in

1947, the other Jawaharlal Nehru’s inaugural address as the first Prime

Minister of newly independent India, all overlaid with plangent vocals. “I

would not like to be called a ‘political’ artist, rather just an ‘everyday’

artist as politics is part of our daily lives . . . “.

Yto Barrada’s photographs show economic migrants asleep in a park in

Tangier as they prepare to undertake the dangerous journey to “fortress”

Europe. Barrada explains that "to cross" is called "to

burn": “you burn your past, your identity, your papers, because if you're

caught on the other side if you're from Algeria you may get permission to stay,

because of the political situation; if you're from Morocco you're sent back

right away. So there's this obsession to get on the other side where the grass

is greener that animates the streets of the city of Tangier, that governs

everything you do from the morning to the night”. Further south we see stark

photographic portraits of sugar-cane cutters by the South African Zwelethu

Mthethwa.

The Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari’s touching and witty film “Tomorrow

Everything Will Be Alright” depicts an epistolary dialogue between two former

lovers: we watch as one types out questions about their relationship on a

manual typewriter and, in a nod to the fact that they haven't communicated for

a decade, the responses instantly arrive on-screen.

The Delhi-born Amar Kanwar’s half-hour film “A Season Outside”, about

the violence and disruption on the Kashmir border between India and Pakistan

(only last week two Indian and two Pakistani soldiers were killed in

skirmishes), opens with the extraordinary flag-lowering ceremony that takes

place at the border gates at sunset - an apparent show of strength on both

sides - and develops into a personal meditation on the intractable

problem.

There are striking works by the Pakistani miniaturists Imran Qureshi and

Shahzia Sikander - “I think that in the West you have a false idea about

Pakistan. It’s believed and wrongly so, that we are gagged and limited in our

artistic production”, writes Imran Qureshi.

Elsewhere we have Ai Weiwei’s compacted, lightly scented and

all-too-tactile (my companion was gently admonished for fingering it) cubic

metre “A Ton of Tea”, apparently made of “Pur Er blend of tea as it is drunk by

ordinary Chinese citizens across the country”.

A centrepiece of the last room is the South Korean artist Haegue Yang's installation, partly made

from Venetian blinds, "Holiday for Tomorrow" (above), which has a curiously labyrinth-like effect.

January 12, 2013

Should book reviews draw blood?

Our classics editor, Mary Beard, made the shortlist for the first Omniture Hatchet Job of the Year, a prize for the "angriest, funniest, most trenchant book review published in a newspaper or magazine in 2011"; and in the TLS this week, in the following extract from the diary column, NB, J. C. acknowledges that this kind of prize is "good fun", unless you happen to be one of the hatcheted victims.

But is it necessarily a good thing to encourage reviewers in the direction of critical savagery? As suggested below, there may be a more difficult task for a responsible critic than simply wielding the axe (for a few recent instances of the more balanced review, see Gerald Mangan's piece on Alasdair Gray, Jonathan Bate weighing up several Keats-related books, or Niki Segnit on Nigel Slater et al). . . .

By J. C.

About once a year, there is a mini-debate about the timidity of book reviewing. It’s been going on for a long time. “Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns.” That was Elizabeth Hardwick, in 1959. More recently, a writer in the online journal Slate suggested that the blogging, tweeting free-for-all that sometimes passes for criticism fosters too much “niceness”, not necessarily a nice quality.

To halt the saccharine spread, the not-so-nice sharpened their tools and carved out the Hatchet Job of the Year. The first award went to Adam Mars-Jones, for a review of Michael Cunningham’s book By Nightfall, and the shortlist for the second has been announced. There are eight nominations, including Richard Evans’s review of A. N. Wilson’s Hitler (“It’s hard to think why a publishing house that once had a respected history list agreed to produce this travesty”; New Statesman), Claire Harman on Silver: A return to Treasure Island by Andrew Motion (“at every turn the former Poet Laureate clogs the works with verbiage”; Evening Standard), Allan Massie on Craig Raine’s novel The Divine Comedy (“some of the writing is very bad”; Scotsman), Camilla Long on Rachel Cusk’s story of her marriage break-up, Aftermath (“quite simply, bizarre . . . acres of poetic whimsy and vague literary blah”; Sunday Times) and Ron Charles on Martin Amis’s “ham-fisted” Lionel Asbo (Washington Post).

The favourite is likely to be the review by Zoë Heller of Salman Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton, which appeared in the New York Review of Books last month. One commentator had already relished it as “a hatchet job among hatchet jobs”; another welcomed the “most pointedly brutal review” of 2012.

Brutality is never nice. Enjoying a healthy demolition as much as anyone, however, we reached for Ms Heller’s piece with a certain shameful anticipation – only to discover that it is thoughtful and well-written, not in the least brutal; on a par with the excellent review of Rushdie’s book in the TLS by Eric Ormsby. Hatchet-job prizes are good fun (not so much for Rushdie, Cusk and others) but it would be unfortunate if critics felt they were being urged to draw blood, to show off their “sharp” edge. The reviewer’s chief responsibility is to the potential purchaser of the book, who, unlike the reviewer himself, is asked to pay hard-earned cash for the product. The most difficult task for a reviewer is to remain true in writing to the feelings experienced while reading, to convey them in elegant, entertaining prose. It’s a lot tougher than being brutal.

January 9, 2013

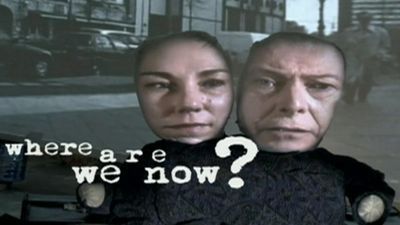

Where is David Bowie now?

By ALAN JENKINS

Reality, in 2003, was a big hit and by no means an inferior work, even by the standards – the highest there are, in popular music – of David Bowie. News, alarming news, to his admirers, followed a year or so later: he had suffered a heart attack, he was exhausted, he was retiring from music-making to spend the autumn of his days with wife and daughter in New York. Ten years on and, on the eve of his sixty-sixth birthday, without so much as a whisper of pre-publicity and with barely a twitch on Twitter, he has released a new song on his website – a song-plus-video, a hybrid form mastered early by Bowie, and never done better by anyone else – which has instantly become the most-downloaded song currently to be heard on the planet.

If there are any visitors to this website who don’t know who David Bowie is or don’t care what he does, I can only ask them to give five minutes of their time to Where Are We Now? – song-plus-video – and share in the elation I imagine all TLS readers must feel at the arrival of a masterpiece. It is a slow, very slow song, full of brought-low sadness and high drama, announcing itself from its first crashing piano chords as utterly, inimitably a Bowie song – and a “big” one, perhaps a huge one, of the magnitude of Always Crashing in the Same Car, Heroes and Fantastic Voyage; and it is to the musical and emotional ambience – whirling synthesizers, echoey drums, throat-tightening melody, hair-raisingly exposed, yearning lyric – of Bowie’s great Berlin years, the years of Low, Heroes and Lodger, that this song explicitly, elegiacally returns. There is an “I”, and a “you” the singer addresses, and a litany of Berlin place-names, sites of memory haunted by a man “lost in time” who is, he says, “walking the dead”, all evoked in a defiantly tremulous vocal line that gathers itself to the great operatic outcry of a refrain, “Where are we now?”. To those who are used to hearing the thunderous climax of “Heroes” – “I, I remember, standing by the Wall /… And the guns shot above our heads / And we kissed / As if nothing could fall / And the shame / Was on the other side” – or the terrible climbing crescendo of “Fantastic Voyage” – “And I’ll never say anything nice again, how can I”? – echoing round their heads at variously unpropitious moments, the shiver of recognition and sombre, paradoxical joy they feel will be familiar.

Almost from the first and unfailingly ever since, Bowie has been a byword for musical boldness and invention. His instinctive power as a lyricist has perhaps been somewhat overlooked – his characteristic note a combination of the shy and portentous, of confessional detail and unembarrassed declamation, of raw truthfulness and authentically barmy allegorizing. “Where…?” takes us haltingly into personal history and personal mortality, distilling from its simple, beautiful progressions an atmosphere of bewildered sorrow that is not entirely dispelled by the tender-stoical declarations of the final moments. There are accompanying grainy street scenes, pre- and post-Wall, there are cluttered, semi-darkened interiors and the truly weird puppet-cartoon presentation of the singer and an unidentified female companion, faces stuffed into fairground frames, she listening with unabashed curiosity and occasional delight as he sings – his own face cruelly distorted to a semi-caricature of ageing and grief. “We could steal time”, Bowie sang in “Heroes”; the singer of “Where Are We Now?” knows that time is stealing him, his friends, his life. The whole is absorbing, harrowing, moving, with the familiar-and-strange unforgettableness that Bowie more than any living musician (and more than most living poets) seems able, time after time, to achieve.

January 7, 2013

Stories of Sean O'Faolain

By MICHAEL CAINES

Readers of the current TLS (January 4) who find themselves at a loss, after encountering Declan Kiberd's masterly lead review about Sean O'Faolain and his magazine The Bell, about what to read next are hereby advised that they could do a sheer country mile or two worse than seek out a copy of O'Faolain's short stories.

(That's the cover of Penguin's 1970 selection reproduced above, cheerfully embedding him in the Irish landscape.)

This would be in keeping Professor Kiberd's suggestion that O'Faolain was "perhaps" a better writer of short stories than of novels, with what they call deftly drawn pieces such as "Discord" (between two newlyweds and a priest) and "The Judas Touch" (in which a boy prays to an "ould jug") in mind. Others more confidently identify him with the genre (no "perhaps" required for this "master of the short story" when he died in 1991, apparently), and agree with the author's judgement that in the writing of short stories he had found his "proper work". There is also a short story competition in his name, held by the Munster Literature Centre since 2002.

It's disarming, then, to find that 1970 selection beginning with a preface in which the author admits that when he started out, in his twenties, he did not know "from Adam what I wanted to say", "dazed" as he was by the "revolutionary period in Ireland" – an experience (not least "the disillusion at the end of it all") that would also shape the mid-century, censor-haunted world of The Bell.

O'Faolain went on, he says, not knowing "what was happening to me or what I was doing" with the form ("Writers never do"), into the time of The Bell, wrestling with the struggle between romantic and realistic attitudes to Ireland, then finally heading in the general direction of satire. But even these efforts are failures, "largely I presume . . . because I still have much too soft a corner for the old land. For all I know I may be still a besotted romantic!" Others, such as Patrick Kavanagh, would have raised an eyebrow at that one.

Some of these supposed failures have been ranked with the best of the twentieth century. Writing in the TLS in 2000, the author's daughter Julia O'Faolain could proudly quote V. S. Pritchett: "Of all the Irish writers, Mr O’Faolain seems to me the most authoritative and diverse". It's true, she would have agreed with Declan Kiberd, that his star has waned in recent times; perhaps a revival is overdue.

January 3, 2013

The wounded Earth

A man walks along a damaged street in the city of Homs, January 1, 2013. REUTERS/Yazan Homsy

"Enough of War the wounded Earth has known;

Weary at length, and wasted with destruction,

Sadly she rears her ruin'd Head, to shew

Her Cities humbled, and her Countries spoil'd,

And to her mighty Masters sues for Peace . . . ."

From Act Three of Nicholas Rowe's Tamerlane (1701), a once popular verse drama about – among other things – a tyrant (admittedly Turkish rather than Syrian), his downfall and the irreparable damage he does . . . .

January 1, 2013

Tony Greig and CMJ

by Adrian Tahourdin

What a terrible week it has been for cricket. First came the news of the death on December 29 of the great South African-born all-rounder Tony Greig, at 66. This morning we heard that the cricket commentator and author Christopher Martin-Jenkins has also died. He was 67. Both had cancer.

Much has been written about Greig’s huge contribution to the game: his swashbuckling style, aggressive batting, canny bowling and brilliant fielding; his inspirational captaincy and ability to play a crowd - as well as his occasional faux pas such as when he promised that he would make the 1976 West Indies team grovel, words rammed firmly down his throat. He took the humiliation with good grace.

And then there was his role in revolutionizing the game when, as the Australian tycoon Kerry Packer’s hired hand, he led a player revolt against the cricket establishment that resulted in international cricketers (in England at least) finally receiving a respectable wage. After that came three decades as an enthusiastic if not strident commentator on the game - “Right off the meat of the bat” - in that broad South African accent he never lost.

Christopher Martin-Jenkins, or CMJ as he was universally known, was by contrast measured, precise and a master craftsman both as a cricket writer and commentator. To many (myself included) he remained the voice of cricket, his beautiful mellifluous tones crackling over the airwaves from Port of Spain to Delhi to Sydney. Phrases stick: “England are sinking, and sinking fast”; “Holding, gliding in from the Kirkstall Lane End” . . .

He was an expert scene-setter as well: if anyone could - in that perhaps overworked notion - make you feel that you were there, at the ground, CMJ could. He was also a stickler for correct usage and grammar, and a brilliant mimic.

From a personal point of view, the two were most responsible for my obsession with the game which started when I casually turned on the TV one idle summer day in 1975 and watched Tony Greig make a brilliant 96 against Australia - Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson - at Lords in his first Test as England captain. I was hooked, and subsequently discovered Test Match Special commentary on Radio 3, with John Arlott, Brian Johnston and CMJ permanent fixtures at the mike.

In a short tribute to Tony Greig published in The Times yesterday, Christopher Martin-Jenkins talked of the care Greig will have received in his final days from “wonderful health workers”. How poignant that generous comment now seems.

December 28, 2012

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 12

By J. C.

Perambulatory

Christmas Books, 6th series, part XII: summary and conclusion. You can obtain

practically any book you want nowadays, from AbeBooks (we use it, too). You can

store a hundred texts (not books) on the e-device of your choice. You could

probably replace your entire life with a computer memory stick. We advise

against, if only because you would be depriving yourself of the pleasures of

perambulation: the rainy autumn street, the dim interior, the erudite owner,

the resident eccentric (there’s always one). Most of all, the serendipitous

discovery of writer and book.

Some

years ago, taking a stand against the anti-festive curse of the Christmas gift

book (Can’t Be Arsed, How To Talk Like an Arse, etc), we pledged to unearth, in

the weeks leading to Christmas, a neglected work by an established author, from

a second-hand bookshop, for about £5. The guidelines may be followed liberally.

It was pleasing, this year as before, to explore shops new to us: Black Gull

Books, Collinge & Clark, Books for Amnesty. We revisited neglected shops

and entered with glad heart again the Archive Bookstore, My Back Pages, Walden

Books. We fret about Keith Fawkes in Hampstead – the Flask – beleaguered by a

bric-a-brac street market. Favouritism is invidious, but for quality,

frequently renewed stock, reasonable prices, Any Amount of Books on Charing

Cross Road cannot be beaten.

For a

final perambulation, approaching the shortest day of the year, we followed the

Thames to Kew. The Green ought to be one of London’s most picturesque public

spaces, with the Church of St Anne and the Green itself still as in Pissarro’s

paintings. But road traffic thunders in one direction towards the bridge, and

in the other to Mortlake. On the hard shoulder, inviting but stranded, is

Lloyd’s of Kew. It specializes in botany, with sections dedicated to literature

and the like.

Is there

a more neglected post-war English writer, relative to former success, than John

Braine? Few could name any of his dozen novels besides the obvious one and its

sequel. Are they worth reading? The Vodi; These Golden Days; The Jealous God?

One perambulatory day, we might try to give an answer. At Lloyd’s we stretched

up to the B’s and picked the obvious one. On the train back, we began to read –

and were immediately hooked again. Room at the Top is the work of a first-rate

writer, only thirty-five when the novel was published in 1957. The bright,

middle-class setting – “T’Top” – is well established, in contrast to Joe

Lampton’s dingy Dufton background; the promise of sex is omnipresent (the

obligation to marry hangs over it); period, post-war detail is vivid. Joe has

never been in a “drawing-room” before. Here he describes that of Mrs Thompson,

in whose house he is a lodger:

"There was

a radiogram and a big open bookcase and a grand piano; the piano top was bare,

a sure sign that it was used as a musical instrument and not an auxiliary

mantelpiece. The white bearskin rug on the parquet floor was, I suppose,

strictly Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, but it fitted in, added a necessary touch of

frivolity, even a faint sexiness . . . ."

After the

film with Laurence Harvey and Simone Signoret, it was down from T’Top all the

way. For a fine first edition, published by Eyre & Spottiswoode in 1957,

easy on the eye and in the hand, Lloyd’s charged us £6.

December 20, 2012

Obelix goes to Belgium

by Adrian Tahourdin

Poor old Gérard. He’s been getting a

bad press over the past few days. I guess anyone who reads a newspaper will be

familiar with Depardieu’s dispute with the French government over his decision

to relocate to Belgium.

For anybody who is not: next year

François Hollande’s Socialist government will introduce its 75 per cent tax

rate for those earning more than €1million per year. Depardieu, unhappy at this prospect and a

declared supporter of Hollande’s predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy, has been engaged

in a slanging match with the prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, who described

the actor’s decision as “pathetic”. Depardieu published an open letter to

Ayrault in the widely circulated Journal du Dimanche, in which he offered to

hand in his passport.

Le Monde sent two of its reporters,

Florence Aubenas and Geoffroy Deffrennes, to the rue du Cherche-Midi in the sixth

arrondissement of Paris where Depardieu has a townhouse he is threatening to

sell and to the town of Néchin, just inside the Belgian border - and his new home, on the rue Reine-Astrid. The actor is prominent and popular in the rue du Cherche-Midi, owning two restaurants there, and on first-name terms with most

of the shop-owners. He’s even taken steps to keep chain-stores away.

Rue Reine-Astrid in Néchin looks

and sounds dreary. Even Google Street View can’t sex it up. The town

is surrounded by beet fields - it’s a “flat and dull landscape”. But quite a

number of French citizens live there and work in Lille, just over the border.

Has the strong French response to

Depardieu’s decision something to do with the fact that the actor has chosen

Belgium, traditionally the butt of all French jokes? It’s not a stylish move.

After all, the equally starry and hyper-French Alain Delon has lived in

Switzerland since 1999 and no one, I’m sure, has objected to that lifestyle

choice.

Depardieu is France’s most prolific male

star, with over 180 films to his name - from the early Les Valseuses (1974), to

the Asterix and Obelix series. Les Valseuses (which featured Depardieu and the late

Patrick Dewaere, above), directed by Bertrand Blier and also starring Jeanne

Moreau, is possibly one of the most politically incorrect films ever made.

I thought it was very funny when I saw it many years ago, but I can’t imagine

it has aged well.

On the same day as the Depardieu story,

Le Monde ran an editorial in which it ended up questioning the "symbolic brutality” of Hollande’s 75 per cent tax. (The paper had

of course supported him in the elections in May.) Even if Depardieu does hand

in his passport he’ll still be able to vote in France. It’s unlikely that he’ll

be backing Hollande.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers