Peter Stothard's Blog, page 71

August 29, 2012

Modern classics before they became modern classics

By MICHAEL CAINES

"A modern classic rarely seems able to venture out on to the bookshelves unchaperoned". So D. J. Taylor writes in the recent double issue of the TLS, in a sampling of six recently reissued novels that claim to be modern classics: "it needs a sponsor to plead its case". The sponsor being whoever supplies an adulatory preface, or an obliging line for the front or back cover, to reassure potential buyers that they are not picking up a mere modern non-classic. Louis de Bernières writing in praise of Barbara Pym's Crampton Hodnet. Candia McWilliam in praise of the "purity" and "tension" of In the Making by G. F. Green. And so on.

If you've read Taylor's piece, you'll know by now whether he agrees with such kind assessments or not. But before the books in question became "modern classics" (whatever that means), they were just novels – what did their first reviewers in the TLS make of them? Do the critics agree, across the years, and do they dare to prophesy lasting fame for any of these books? Has the critical language changed out of all recognition?

With such questions in mind, here follows a game of "modern classics" Consequences . . . .

The Blaze of Noon by Rayner Heppenstall

The sponsor says: "an under-appreciated classic of inter-war literature" (G. J. Buckell).

D. J. Taylor says: "the good intentions are sometimes crowded out by straightforward trickery".

And the TLS originally said: Nothing. We didn't review it. (This is a good start.) But when the book was reissued in the 1980s, Valentine Cunningham found it "astonishing" that the novel could once have been acclaimed as the "hottest of stuff": "its real interest now consists only in the degree to which The Blaze of Noon was an opportunistically wiggled bit of fly-paper onto which the going interests of the 1930s got themselves dutifully stuck". Others had thought Heppenstall deserved more credit than that: writing in the TLS in 1963, Julian Maclaren-Ross drew the lines of connection between autobiographical experiments such as The Blaze of Noon and Alain Robbe-Grillet.

In the Making by G. F. Green

The sponsor says: "Pure, tense, and incontrovertibly a modern classic" (Candia McWilliam).

D. J. Taylor says: "If Green has a weakness for deep-romantic-chasm adjectives like 'tenebrous', then some of the special effects . . . are startlingly good".

And the TLS originally said: "Mr. G. F. Green has written an overcharged, oversensitive account of a boy's childhood and youth" (Julian Symons). And like Taylor, he noted the novel's unfortunate fondness for words such as "peradventure".

Harriet by Elizabeth Jenkins

The sponsor says: "Forged from the unpromising prolixity of a Victorian courtroom, a powerful synthesis of truth and imagination renders it indelible" (Rachel Cooke).

D. J. Taylor says: "Harriet is rather showing its age".

And the TLS originally said: "Miss Jenkins is . . . a novelist of great ability. She has the unusual capacity for seeing clearly what is to be done and doing it completely and precisely . . .".

The River by Rumer Godden

The sponsor says: (I've misplaced my copy. Sorry. But I think we can safely say that they liked the book.)

D. J. Taylor says: The River "not only has trouble disguising its origins as a memoir of the author’s childhood (sans the violent climax) but also betrays its 'young adult' status by a faint air of didacticism".

And the TLS originally said: "The River is a short and delicately told tale of an Anglo-Indian family living in Bengal." It is "gently written and deftly constructed". It is a "pleasant little book". That was in 1946. Twenty years later, Paul Scott could write of the "magic-in-recollection" of Godden's novel in combination with Jean Renoir's film.

Crampton Hodnet by Barbara Pym

The sponsor says: "An entertainment that is funny, poignant, observant and truthful" (Louis de Bernières).

D. J. Taylor says: "the effect is rather like a Firbank novel with all the blood drained away".

And the TLS originally said: "One only wishes that the editors had relieved it of its hideous provisional title when they rescued the manuscript from undeserved obscurity in the Bodleian Library." There were other problems, Miranda Seymour thought, with plot, characterization, jokes and excessive recourse to "tea-and-scandal sessions". But these were "inconsequential" faults in a novel "so richly endowed with Pym's clear intelligence".

Mrs Bridge by Evan S. Connell

The sponsor says: the eponymous heroine of Mrs Bridge is "a reflection of you and me, an exemplar of our shared humanity and all the terror and opportunity it so briefly provides" (Joshua Ferris).

D. J. Taylor says: "On more than one level, Mrs Bridge’s great – in some ways its only – theme is survival. For all the rueful comedy that surrounds her life, its heroine’s chief task is to endure the battering of an indifferent and naturalistic world. In doing so she advertises some of the qualities necessary for a novel to extend its usual chronological span, transcend some of its built-in limitations, defy obsolescence and go on living. Identifying these bench-marks is not always easy: usually the reader merely notes a taxonomic black hole, an uncategorizable resonance that the other sheep whipped into the modern-classical pen mysteriously don’t possess. But whatever they are, Evan S. Connell has them in superabundance".

And the TLS originally said: Do we have a "small masterpiece on our hands"? Mrs Bridge was a book David F. Williams could praise as "often funny, sometimes tragic, always tenderly ironic".

As in Taylor's round-up, then, the points go to Evan S. Connell.

Note, however, that in his review of an earlier reissue of Mrs Bridge in 1983, David Montrose could assert that the sequel, unsurprisingly titled Mr Bridge, was the "better novel". Has the publisher missed a trick?

Of course not: Penguin plan to reissue Mr Bridge in the spring.

August 22, 2012

August 31 . . .

is the date of the next issue of the TLS, in case you were wondering. Last week's TLS, that is, was a "double issue", and there won't be a new one out this Friday. People do sometimes get confused about this . . . .

(You can, however, now read a fresh selection of pieces from last week's issue online, including Maria Golia's round-up of books about the Arab Spring, Carol Birch's appraisal of the not-so-dead British short story and Michael Anderson's review of a memoir by the "Cinderella Gentleman" himself, Harry Belafonte.)

August 20, 2012

Sprint for Shakespeare - or beware Bohemian bears

BY PETER STOTHARD

Every day the Durrants company sends the Man Booker judges the latest advice, speculation and comment on our work from the pages of the press.

For those of us with long newspaper memories this is still a strange arrival. The name Durrants means to me those old library envelopes in which their cuttings service used to be kept last century, the cuttings that were prey to chaos and carelessness in every newspaper office but which were still the nearest thing to permanence that most of our articles ever had.

Now, of course, Durrants is all electronic, a line of blue www-type in place of the yellowing print. But by Durrants we Man Bookerists still get to know how we are seen — from Bombay to Bournemouth — and which of our long list is judged the most worthy or likely to win the prize in October.

Alongside my distinguished and industrious colleagues I have been living with this decision all year. We now have a long list of twelve from an original cast of 145 novels. And in a few weeks we will have a short list of six.

But shhh! Say it quietly. For the past few days the Chair of the Man Booker judges has been off the job. Guiltily (for with our long dozen to reread and reread by the end of the month I ought not to be straying) I have been reading The Winter’s Tale instead.

This has been almost purely for pleasure. I will not deny the pleasure in judging our list. But that should not be the purest pleasure. Criticism is a form of work. Judging the Man Booker Prize is and ought to be hard work.

So, instead, I have had the Arden Edition in my hand of what I once thought was my favourite Shakespeare play. Maybe I still do think that. Fortunately, I am not going to have to explain later this year precisely why — and not to writers of Durrants clippings. Pleasure can be unexplained. Let’s say that The Winter’s Tale would certainly make it to my short list.

Still do I feel guilty? Yes. But Shakespeare, I persuade myself, does have his Man Booker role too. He clears the mind. By being above all English others he puts lesser distinctions in their place. I am going to be a better reader next week for having spent some time with him.

Or shhh! That is my excuse. Mostly I have merely been enjoying myself.

There has been just one problem. I have not been rereading my probably favourite play in the form that I would now most like to have it. I have been seduced by something that does not yet exist.

Think electronic. Man Booker judges have this year become pleasantly accustomed to paperless readings — both of the new novels themselves and the latest articles about them. And for the past two weeks a new electronic offering has been dangled before me. I want it now.

The Bodleian Library, as I have discovered, has been holding out the prospect of a digitalised version of its1623 First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. The only authoritative text of The Winter’s Tale is in this most magical of magic books.

The Bodleian Library, as I have discovered, has been holding out the prospect of a digitalised version of its1623 First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. The only authoritative text of The Winter’s Tale is in this most magical of magic books.

Oxford’s electronic task, I am told, can readily be completed. It can be made to happen. The magic of the Bodleian First Folio can be made to appear on my screen, everyone’s screen, anywhere, everywhere. But not until we have £20,000.

Only £20,000. The library is challenging its supporters to what surely should be only a short race, a Sprint for Shakespeare, to contribute cash, £20 at a time, in the modest spirit of every little bit helping.

Why do I want it? Why do we want it? You may well ask. Are we being picky pedants here?

Do we want it so that, for example, the shift-working compositors of the Folio, with their different approaches to spelling do and go can be seen by anyone anywhere? Well yes. That is one reason. Do we want to wonder on the 43 stage directions, including the peculiarly famous ‘Exit, pursued by a bear’, and what they tell us?. Yes, we do.

And then what sort of play is it? What did its first publishers think that it was? Where did it fit? That is another reason? There are a thousand indefinable others. Every copy of the First Folio has its own secrets.

Of course, like everyone else, I have lived happily for many years without the yearning to read this first Oxford text, anywhere, at will, in its first form. But, knowing it is possible to have it, I now want it rather badly. Man Booker judges and all literary critics can be as electronically demanding as anyone these days. Why should we not be?

I have even agreed to join the ‘champions’ of Sprint for Shakespeare. Vanessa Redgrave is our leader. I want this to happen. We have have agreed to help the Bodleian to raise the money. So please help. Give something, anything, some money, any money.

This is not what I normally do. I do not think that I have ever been a ‘champion’ of anything before. Give a little. Or give a lot.

Or beware the bears of Bohemia.

August 16, 2012

An Ira Aldridge mystery

By MICHAEL CAINES

A couple of months ago, Douglas Field reviewed a new two-volume biography of the celebrated nineteenth-century actor Ira Aldridge, the "African Roscius", the "first black actor of note". We know that he played Othello (predictably) and was eventually to add a "Jim Crow song-and-dance routine to his act", once he got to touring the English provinces during the 1830s (he was American by birth but was by then claiming to be a "scion of Senegalese royalty").

But what about his other roles – and in particular the role depicted in this painting, recently discovered in a garage in Birmingham?

Apparently, nobody has yet worked out what part Aldridge can be playing here. It seems to have been a performance – or a moment in a performance – sufficiently admired for somebody to want to preserve it (or embellish extensively on the barer bones of a theatrical scene; the dog cowering beneath the table would suggest as much).

Noting the pistols and the crate being lowered by pulley towards a trapdoor, you might well look for a play of the time with a title such as The Algerian Pirate, The Pirate of the Islands, or Will Watch, the Bold Smuggler. You might look into that new biography by Bernth Lindfors, in which all of these dramas are mentioned. But would you be able to lay hands, virtually or not, on copies of the likely suspects? Probably not, unless you happen to be blessed with access to the right research library. Which isn't necessarily the biggest or most obvious one: a quick catalogue search would suggest that the British Library itself would not be much help at all.

The man who found the painting, Stephen Howes, says he is "committed to keeping it in the UK and until all the pieces of the puzzle fit together”. So it might be here for some time yet.

Idly looking for Aldridge online, however, at least makes clear how much he stood out among the actors of his day, as in the mysterious painting, and how useful that was to him. "The African Roscius is the only actor of colour that was ever known", he seems to have told people, "and probably the only instance that may occur."

In Birmingham, where the painting seems to have lain unknown for some time, he was greeted as a "most extraordinary novelty", while a Glasgow periodical called The Ant conveys the same raising of the eyebrows when it reports on a man playing Othello "without needing to blacken his countenance". Novelty aside, some more disturbing comments follow. The Scottish correspondent goes on to credit Aldridge with "surprisingly distinct" enunciation, and is momentarily troubled by the thought that he might possibly be worthy to essay a Shakespearean role. But ultimately he declares the foreigner's "physical energies, like his stature" to be "beneath the European standard".

Oh for a time machine that could scoop up such a perceptive critic and deliver him to the Noel Coward Theatre, in time for tonight's (all-black) performance of Julius Caesar.

"Like his stature", though: can this be the same actor who towers over the other figures in this enigmatic image from dramatic history?

August 13, 2012

Lovely Serpentine

by Adrian Tahourdin

Well, the Games are over. The general feeling is that they went pretty well. They were certainly very enjoyable — even if the closing ceremony seemed interminable. Spice Girls, anyone?

I earlier expressed disappointment at not getting tickets for events at the Aquatics Centre (see post, June 21), but partly made up for it by seeing the Men’s Marathon Swim, a 10 kilometre event (10k, without any breaks!), which was held in the Serpentine in Hyde Park. There was a small temporary stand of ticketed seats, but most of us were in the unticketed areas all around the Serpentine which, I have to say, looked an absolute picture. The atmosphere was fantastic and the sun even shone.

The swimmers were attended by a whole flotilla of inflatables and canoes, while the feeding/refuelling pontoon was an extraordinary sight as the competitors poured liquid down their throats before swimming off. The Tunisian Oussama Mellouli won gold in a time under 2 hours, the first swimmer to win medals in both pool and open-water events (he won a bronze in the 1,500m freestyle). Six long laps up and down the lake, which didn’t appear to be taking it out of him at all. He seemed pretty pleased: “I can’t explain it, I can’t really describe it. What happened today is a miracle . . . “. Mellouli had vocal support too (see below).

But the biggest cheer was reserved for the swimmer from Guam, Benjamin Schulte, who finished nearly ten minutes behind the next-to-last (out of only 25) and had his own little flotilla by the end. This was the Olympic spirit at its best: the crowds driving him on coupled with his determination to finish. Great stuff.

August 10, 2012

The Law Society vs Joseph Mendham

By MICHAEL CAINES

Great book collections are constantly rising and falling – to the horror of book historians, when they realize that unique incunabula have vanished for ever, or that some insight into how a writer's mind worked has disappeared along with their library.

If you read the "In Brief" reviews of the TLS, you'll (surely) remember David Finkelstein's brief account of what happened to the collection of some 16,000 books belonging to the humanist scholar Gian Vincenzo Pinelli, published a few years ago: the attacks of Turkish pirates accounted for a third of it, as it was transported to Naples after Pinelli's death; the Allies bombed the rest out of existence during the Second World War.

Less dramatic but somehow more puzzlingly uncivilized than that is the current action of the Law Society of England and Wales – already condemned by the religious historian Diarmaid MacCulloch as "vandalism", and the subject of an online petition – in seeking to break up the unique collection of books made by the nineteenth-century clerlgyman-controversialist Joseph Mendham.

Mendham (1769–1856) was an Anglican clergyman with a private income (hence the accumulation of unique manuscripts and rare incunabula). He was an inveterate nineteenth-century opponent of Roman Catholicism; his railings against the Index of prohibited books make particularly impressive reading, and required deep knowledge of a great range of Continental literature on the subject; he brought together over eighty separate editions of the Index librorum prohibitorum.

The odd thing is that the Law Society owns this collection, and acknowledged its intellectual worth in the 1980s by loaning it to Canterbury Cathedral Library (which has ties to the University of Kent) – but, last month, they sent the men from Sotheby's down to the Mendham Collection to remove a selection of the most valuable items in order to auction them off and, as Kent's Dr Alixe Bovey has put it, "plug a hole in their finances". (Something has gone wrong, apparently, since 2009.)

So, come the auction in November, out goes the unique 1495 edition of Guy de Montrocher's Manipulus curatorum; out goes the only known survivor of the Modus confitendi of Andreas de Escobar from 1480; and it's goodbye to the Mendham copies of Donne, Aquinas and several editions of that notorious Index. Unless you and a couple more thousand people sign that petition, perhaps.

As Elaine Treharne has put it, the point is not so much that the lawyers need or want to sell a few books in these difficult times. It's that these particular books (which include, incidentally, the owner's annotations, further marking them out as his) belong together. The "deliberate dispersal of an historic collection" is a desponding prospect: "deliberately fragmenting historical evidence of the passions and pursuits of earlier collectors impoverishes our human record". Tell that to the pirates who just want to plug a hole. . . .

August 8, 2012

The humanities online

By MICHAEL CAINES

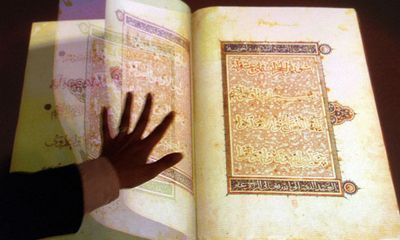

“Armed with computers, humanities scholars have been performing once-unimaginable feats. They have recreated early modern London and American Civil War battlefields with the help of geospatial imaging. They have trawled, or 'text-mined', the vast corpus of Google-digitized books to establish how many times certain words or linguistic patterns appear. They have created a searchable database of almost 198,000 trials held at the Old Bailey between 1674 and 1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org). They have mapped the Republic of Letters by tracing the journeys of 50,000 letters written and received by Voltaire, Locke, Franklin and other seventeenth- and eighteenth-century luminaries (https://republicofletters.stanford.edu/).”

For anybody interested in the current debates among the "digital humanists" about these once-unimaginable feats and what could and should be done next: Jennifer Howard's review of a new collection of essays on that subject is now freely available online on the TLS website; it also appears in print in this week's TLS, along with pieces on Jane Austen, Rousseau, Gore Vidal and . . . Manchester City FC.

It's a widely ranging piece, taking in "spirit of open, collaborative experimentation" that "inspires much of what digital humanists do", as well as the humanities' "gnawing sense of irrelevance", from which digital projects are not immune. (See the photo above for a flagship example, the British Library's digitized version of the 700-year-old Sultan Baybars' Qur'an.)

But rather than repeat here what Jennifer Howard says so well, I'll just note the fine coincidence that, on the day we put online a piece about how digital humanists are currently revising their expectations of their work, and debating what happens next, if you follow the second link above, for the extraordinary Republic of Letters website, and this is what you see:

(The two lines below the website's logo read: “Mapping the Republic of Letters is undergoing an upgrade. It is all happening today.”)

Just a coincidence, of course. But somehow appropriate . . . .

July 30, 2012

Scandalous books

by Adrian Tahourdin

Proust once contributed articles to it, but Le Figaro is not a newspaper I've ever been in the habit of looking at. Yet I couldn't help noticing recently that it was running something entitled "Ces Livres qui ont fait scandale", a 24-part series on books that created a stir when they first appeared.

This must be the Figaro's equivalent of its great rival Le Monde's imaginative ploys to fill its summer pages. For example: last summer Le Monde published an entertaining long-running fictionalized account of Jacques Chirac's time as president.

Le Figaro's scandalous books series is confined to the 20th century, and kicks off with Lolita - turned down by four publishers in the US but taken up by Maurice Girodias of the Olympia Press in Paris.

Girodias also had a hand in the publication of Histoire d'O. As Mohammed Aissaoui reminds us, the true identity of its pseudonymous author Pauline Réage was only revealed in 1994 as Anne Desclos, who had earlier published an anthology of religious poetry. Histoire d'O was made into a film in 1975 by the aptly named Just Jaeckin.

Dominique Guiou takes us through the scandal surrounding the publication of Michel Houellebecq's Plateforme which appeared in August 2001: not only did the novel depict, in graphic detail, scenes of sex tourism in Thailand, but in an interview with the magazine Lire at the time of publication the author made some offensive remarks about Islam, which landed him in court. Houellebecq was found not guilty in October 2002 of "provoking hatred".

Blaise De Chabalier writes about Boris Vian's shocker J'Irai cracher sur vos tombes (translated as I Spit on Your Graves), a pastiche of American noir thrillers which Vian published under the pseudonym Vernon Sullivan in 1946. The court case that followed helped turn it into a bestseller. Vian died of a heart attack during the first screening of a film version (which he didn't like) of the novel in 1959. I never saw that film but I did see an American video-nasty version of the book in the 80s - not as shocking as the book had been.

Inevitably there is a political angle to the series: a pamphlet attacking de Gaulle that appeared during the 1964 presidential campaign and was condemned for causing offence to the head of state. Stéphane Courtois's Black Book of Communism is featured - not surprising in the right-leaning Figaro.

Anne Fulda takes us through the dramatic and life-changing events surrounding the publication in 1988 of The Satanic Verses (1988). When the fatwa on Salman Rushdie was pronounced by the Ayatollah Khomeini in February 1989 George Steiner appeared on the news, ringingly invoking Voltaire's defence of the writer to publish and offend. Steiner also had it on good authority that the book was "unreadable". The unfortunate adjective seemed to attach itself to the novel, yet it was far from being the case: dense yes, multi-layered and playful, but far from unreadable. In the words of Robert Irwin, writing in the TLS, it was "several of the best novels Rushdie has ever written".

The series continues, most recently with Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho, published in 1992. It's striking how many of the books featured went on to become bestsellers. And the Figaro has gained a new reader.

July 26, 2012

Bibliographical altruism

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Cultural diagnosticians may have registered a micro-trend – “lucy-dip reading” – that blipped almost imperceptibly across their monitors sometime between 2010 and 2011. The general idea was that many readers had lost the love – the art – of browsing titles and subjects, resulting in a shrunken book pool from which to draw.

Online stores have compounded this with title/author/keyword search facilities that turn up exactly what you want, when you want it. (Auto-complete fields are particularly useful, or limiting, depending on your stance.)

So what can we do to prevent bibliographic myopathy? Readers of the TLS’s N.B. column will know that the “essential disarray” of second-hand and charity shops can be a fine tonic, with generally pleasurable side effects, as can be projects such as Book Swap, which operates in a similar way online. In the past, it has also been suggested that people leave books lying about in public places – on train platforms and park benches – for strangers to pick up and take home; they might then do likewise. (This is beautifully altruistic – the sort of thing someone might make a romcom about – but somewhat impracticable, considering the unpredictable weather.)

I imagine selecting the neighbourhood in which to browse may produce a filtrative effect similar to that of online search bars. I’m tempted to delve into the darkest recesses of the TLS office in search of obscurities to leave dotted about the streets; other editors could drop them off somewhere on their way home, or on holiday…. Helen Dunmore’s “Ice Cream” might turn up on a beach in Scarborough, a history of bagels in a café in San Francisco. Diplomatic relations could by strained if, say, “The Future is…China” were to appear in Delhi, or “India Rising” in Shanghai – but then there might be a copy of “A Cultural Approach to Interpersonal Communication” just a few park benches along.

July 21, 2012

Wotcher, wotcha and what cheer

By J. C.

Readers with long memories will recall a correspondence over the derivation of the cockney greeting “wotcher” or “wotcha”. (NB and Letters, December 2009–February 2010). Most plumped for wotcher as a contraction of “What cheer?”, but the writer Michael Rosen was of the opinion that “the sense of it was ‘What are you doing?’, with ‘what are you’ contracting to ‘wotcher’”.

The poet Kit Wright now gets in touch, apologizing for lateness but happy to present what he regards as a clinching argument. It comes in the form of a music hall song, “What Cheer ’Ria”, written by Will Herbert and Bessie Bellwood in 1885. The story concerns Ria (Maria), “a girl what’s a-doing wery well in the weagetable line, / And as I’d saved a bob or two I thought I’d cut a shine”. Ria buys “some toggery, these ere wery clothes you see” and visits the local music hall – not to sit in the gallery, where her friends are, “but on the bottom floor”, with the toffs. As luck would have it, her pals up in the gods see through her finery and begin to cry:

"What cheer Ria! Ria’s on the job,

What cheer Ria! did you speculate a bob?

Oh Ria she’s a toff and she looks immensikoff,

And they all shouted 'What cheer Ria!'"

As sung, the line comes out as “Wotcher, Ria!”, and Mr Wright is surely correct in believing that the thorny derivation is thus smoothed. When next passing Mr Rosen in the street, he expects to be greeted, “What cheer, Kit”.

Ria’s song is, of course, a moral tale, and a rather dismal one, about the perils of getting above yourself. At the end, having had her dress torn by a toff, she confesses she knows her place: “I felt so wild, to think how I’d been taken down, / Next time I’ll go in the gallery with my pals, you bet a crown”. This picture of either Ria or Bessie Bellwood adorns the front page of the original score, reproduced in Sixty Years of Music Hall by John M. Garret (1976). Now we need to know if “immensikoff” was common usage, circa 1885, and if there are other instances in literature or song.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers