Peter Stothard's Blog, page 73

May 14, 2012

Lewis-Carroll-next-the-Sea

By Thea Lenarduzzi

How did you celebrate International Owl and Pussycat Day on Saturday? Across Britain, people gathered to celebrated the 200th aniversary of the birth of Edward Lear, with recitals and puppet shows, and, worryingly, “animals and nonsense” promised at Knowlsey Safari Park (and entertainment of a safer, academic sort yet to come).

Others got their fix of nonsense elsewhere. I found mine in a small community hall in Wells-Next-the-Sea, Norfolk, on the final day of the yearly poetry festival. The occasion was Lewis Carroll’s unbirthday party (as indeed every day of the year, except January 27, must be), and Dame Gillian Beer led the celebrations with readings from her edition of his collected poems, due to be published in September. (We must speak of the “Collected” rather than “complete” poems, she explains, because “they keep popping up like mushrooms”.) So, while we enjoyed a cup of tea and a biscuit for the wonderfully no-nonsense price of 50p, Beer urged us to look beyond the Alice books, and into the further wilds of Carroll’s – and our – imaginations.

The earliest poems of Lewis Carroll (born Charles Dodgson in 1832) share the verbal intensity, and many of the characters and episodes, of his mature writings. Tracing the genealogy of the poet’s fancy, Beer drew on an exchange of letters between a seven-year-old Charles and his father, who had been called to Leeds on Church business. In response to the boy’s request for “a file, a screwdriver and a ring” – for reasons unspecified – Archdeacon Dodgson declared that he would leave no man or cat alive in the city until his son’s demands had been met: ducks would jump into teacups, children would hide in the mouths of their mothers, quaking in attics, and the Mayor himself would be packed into a suitcase and covered in custard, until the whole resembled a layered sponge cake.

The “cheerful violence” and logical perversions of Carroll’s compositions are evidently rooted in this happy hecticism of family life. By the age of twelve he was already dedicating collections to his numerous siblings. One such project, included in Beer’s edition, is Useful and Instructive Poetry, in which each poem presents a moral: “Never stew your sister”, about a quarrelsome brother who wishes to make an Irish stew of dubious provenance, is a favourite; another, “My Fairy” – in which a child, frustrated by the didactic suffocations of youth, begs “What may I do?” – ends simply “You mustn’t.”

But Carroll’s are not all “funny little poems”, Beer explained. The melancholy of “Solitude”, for example, is surprising:

“I'd give all wealth that years have piled,

The slow result of Life's decay,

To be once more a little child

For one bright summer-day.”

Written in response to the sudden death of his mother, its tone is serious and elegiac – a lament for lost youth composed by a twenty-one-year old, only two days into his undergraduate course in Mathematics at Oxford. This is the first poem to be attributed to “Lewis Carroll”.

Many poems, especially from his lesser known novel in two parts, Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893), are particularly sardonic and disturbing. Their language is bewildering; mathematical theorems and secret codes disorientate the reader and Carroll offers no solutions to the riddles he poses. “I found I just could not follow him there”, admitted Beer.

Not even Carroll stuck to his routes steadfastly, cutting and changing his verse ad nauseam (let's recall the Bellman's map – a blank sheet of paper – in The Hunting of the Snark). “Words always mean more that the writer can possibly know”, Carroll said, and he willed people to take a different approach. Perhaps one of Beer’s most generous points yesterday was her mention of Carroll’s scrapbook. Kept between 1855 and 1872, it is now fully searchable online at the Library of Congress: http://international.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage . Who knows where your browsing may lead . . . .

May 10, 2012

Pallant House Gallery

by Adrian Tahourdin

Pallant House Gallery in Chichester was opened just thirty years ago yet it can rightly claim to be “one of the most important galleries for British modern art in the country”. The bulk of the collection is housed in a discreet and airy modern extension designed by the architects Long and Kentish together with Professor Colin St John Wilson, the subject of one of the portraits on display - by William Coldstream.

Pallant House itself, a beautiful Queen Anne town house, sits in the shadow of the cathedral and was built for Henry “Lisbon” Peckham, his nickname alluding to Peckham’s interests in the Portuguese wine trade. One room is given over to eighteenth-century works: porcelain and glass, a couple of works by George Romney. There is also a remarkable bronze bust of Charles I by Hubert Le Sueur, dating from c.1637; the bust was presented to the city during the reign of Charles II “in recognition of its role as a monarchist stronghold during the Civil War”.

The glory of the gallery undoubtedly lies in its twentieth-century British collection. Among the artists represented are Walter Sickert, Ivon Hitchens, David Bomberg, Patrick Caulfield, Henry Moore (a sombre 1942 watercolour-and-wax-crayon sketch of two people in a bomb shelter), Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, Peter de Francia, Barbara Hepworth, Mark Gertler, Wyndham Lewis . . . . A portrait by William Coldstream of one of the bishops of Chichester seems almost incongruous, although it’s near to a striking depiction by Eric Gill of “Christ the King” in Portland stone, dated c.1935.

A particular incentive to visit the gallery at the moment is the Keith Vaughan exhibition (on until June 10). Vaughan was born in the nearby fishing village of Selsey a hundred years ago. He committed suicide in 1977. Continental influences are palpable in his work, most obviously Cézanne and Picasso, while Cubism is transplanted to a “Village in Ireland”. There is an unsettling quality to it too - one particularly disturbing picture is inspired by Kafka’s The Trial. In the glass cabinets are book cover designs for Rimbaud’s “Season in Hell” among others.

The gallery leaflet describes Vaughan as “best known for his painterly depictions of the male nude in the landscape”, which are indeed amply represented in the exhibition. As Richard Dorment wrote, reviewing the show in the Daily Telegraph, the effect is not “overtly homoerotic” as Vaughan was “working at a time when the open expression of homosexuality in art was not possible”. But with hindsight the intentions are clear. Most eye-catching to me was the Redon-meets-de Chirico of the enigmatic “Night in the Streets of the City” (detail below), with its androgynous faces caught in an embrace.

[image error]

With rain looking likely for the coming weeks, I can't think of a better interior to take shelter than this wonderful gallery. For good measure there are also small exhibitions on the art of Chichester Fesival Theatre and a photographic display by David Dawson, "Working with Lucian Freud".

May 2, 2012

Monarchy and the Book of Common Prayer

by Rupert Shortt

At first sight, the event may seem a little arbitrary: “Royal Devotion: Monarchy and the Book of Common Prayer”, an exhibition being held at Lambeth Palace in London to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and the 350th anniversary of the (1662) Book of Common Prayer. The show displays the Palace Library’s collections of items with royal links. But how many British monarchs can be called devout?

The rationale for the venture became clearer to me on second thoughts. For the three centuries between the Restoration of Charles II and the current Queen’s accession, the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) can be said to have encapsulated much of England’s religious life. Monarchs and countless others were at least baptized, married and buried to its words; and “more people heard Morning . . . and Evening Prayer in weekly services in the words of this book, than listened to the soliloquies of Shakespeare”, as Professor Brian Cummings, a curator of the show and TLS reviewer, puts it.

Visitors can see a remarkable range of books, many owned by kings and queens, and some bearing marginal notes made by them. The volumes on display include a Book of Hours that once belonged to Richard III, and copies of the BCP used at the wedding of Queen Victoria, and at the present Queen’s Coronation.

Inevitably, it is in the to and fro of the Reformation period that the link between throne and Prayer Book is most obviously reflected. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer first heard a Communion service in German at Nuremberg in 1532. A version of this liturgy is shown in the exhibition, along with early examples of vernacular liturgical experiments in England, and the first version of the Eucharist in English, printed in 1548. We also see an example of the Latin prayer books reissued under Mary I, along with the Protestant-tinged English equivalents used by her half-sister, Elizabeth.

More controversially, the exhibition lends support to the notion that Charles I died a “martyr” to Anglicanism. The BCP did eventually incorporate a special service on this theme, but dispassionate observers are likely to conclude that the King’s execution mainly came about because of his political obtuseness. The gloves worn by Charles to the scaffold (pictured above), and an ivory chalice belonging to Archbishop William Laud, are also on view.

The show (which runs in the Palace Library until July 14), lends indirect weight to another claim by the organizers – that the venue itself is becoming unsatisfactory, owing to a lack of shelf space. The current Archbishop, Rowan Williams, announced that excavations had begun “at the bottom of the garden” – that is, at the far end of the palace grounds – to build new library facilities in due course.

April 23, 2012

Madame Woolf

By Adrian Tahourdin

Virginia Woolf’s work has just appeared in the prestigious Pléiade series in France. She is only the ninth woman writer to be granted this accolade, out of 200 Pléiaded writers.

The other eight on the list are: Mme de Sévigné, Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Sand (whose house at Nohant Woolf visited on a trip to France in May 1937, “avoiding King George’s Coronation, as [she] had avoided the Jubilee”, in the words of Woolf’s biographer Hermione Lee), Colette, Nathalie Sarraute, Marguerite Yourcenar and Marguerite Duras. Surprising not to see Mme de Staël in the pantheon. Marguerite Duras’s own Pléiade Oeuvres, which appeared towards the end of last year, will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

The novelist Virginie Despentes reviewed Woolf's Pléiade Oeuvres in Le Monde des livres last Friday. Despentes is the author of Baise-moi and, most recently, Apocalypse bébé. After sketching the life she discusses Woolf’s death, on which she writes: “Le suicide est à l’écrivain ce que l’overdose est au rocker” (suicide is to the writer what overdose is to the rock star). Later she has a slightly strange riff on how the verb “to sink” is close in sound to “to think” - “Couler, to sink, terme si proche de to think, penser” . And “Ouse” as in the River Ouse is apparently a bit like “house”.

Despentes laments the incompleteness of the project: two volumes, of 1,500 pages each, but no room for A Room of One’s Own (Une Chambre à soi), the correspondence or the diaries. Continuing the rock and roll analogy, “it’s as if a record label were to bring out a Rolling Stones greatest hits without ‘Satisfaction’”. Necessary economies on the part of the publishers Gallimard perhaps, but not ones that should have been applied to “Madame Woolf”, in her estimation. But this seems a false objection: surely Gallimard plan a separate third volume. And has Despentes not noticed the title: Oeuvres romanesques?

The fact that Woolf’s work has entered the Pléiade is of course wonderful news. Interest in her work in France is considerable, as evidenced by the publication of Viviane Forrester’s biography in 2009. The sentiment wasn’t always reciprocated: Woolf herself had a difficult reading relationship with her pre-eminent fellow modernist across the Channel Marcel Proust, as a recent letter to the TLS (Charles Elliott, March 30) reminded us.

April 21, 2012

Around the world in one issue

By Thea Lenarduzzi

Readers of this week’s issue of the TLS could be forgiven for thinking, at first glance, that we had forsaken the world in favour of the familiarity of our London home – it is, after all, the city of our birth, 110 years ago. Now, Norma Clarke guides us through the third and final volume of Jerry White’s history of the capital (“bigger, stranger, less graspable than we think”), before entrusting our care to Richard Davenport-Hines in his review of Night’s Out: Life in cosmopolitan London.

Soho in the early 1900s: gone the “Chaos of Dirty Rotten Sheds, always Tumbling or takeing fire, winding Crooked passages . . . Lakes of Mud and Rills of Stinking Mire”, described by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1715, to be replaced by culinary extravagances, knock-out (and knock-off) sartorial experiments and “racy” tourism. Welcome to the jazz age! Of sorts . . . .

“Bright lights, big city, went to my TLS’s head”, you may say, but turn the pages and you will encounter the architecture of modern Russia, where, says Clementine Cecil, “a fondness for old stones has always been the preserve of the dissident voice”.

The Ligurian coast is the setting of Julian Stannard’s latest collection of poems, reviewed in our pages by Joe Kennedy, where, for those already pining for the soft-lighting of Soho, “Bar Degli Specchi” offers “a little slow jazz or even a little low jazz”, which captures the spirit of Genoa. Yet, for those lulled by Stannard’s steady “neo-Romantic sleeper service”, Noo Saro-Wiwa’s travelogue offers a sobering account of “an unpiloted juggernaut of pain”, leading to the heart of her native Nigeria, “where nightmares did come true”.

After a brief stop-off among the “suprises and stereotypes” of post-independence Kazakhstan, we find ourselves running with the wolves in Ireland, exploring the history, folklore and cultural legacy of the beast - albeit from a safe distance.

Somewhere along the way, Jane Jakeman may entice you to the theatres of Egypt in pursuit of Shakespeare’s Danish Prince, but, as we began this journey in London, it seems right to end there – for today at least. Here is an extract from a review by Harold Child from 1902 (yes, the year of our birth), entitled “The Fascination of London”. It shows that our love for the streets of London is nothing if not enduring.

"The last two volumes of Sir Walter Besant’s 'Fascination of London' are 'The Strand District', by Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton, and 'Hampstead and Marylebone', by G. E. Mitton, edited by Sir Walter Besant . . . . Of the two the former is naturally the more interesting. The district, which stretches from the Green Park to Soho-square and from Burlington House to Temple Bar, is particularly rich in literary and personal associations. In St. James’s-Square we see Samuel Johnson and that queer friend of his, Richard Savage, pacing all night for lack of a lodging and parting at dawn with the pathetically high-hearted resolution 'to stand by their country.' Soho-square, where one may still catch sight, through an open window, of some richly moulded ceiling, is alive with memories of wild nights at 'Old Soho’s', as Gilly Williams called Mrs. Cornelys.

In Leicester Field Sir Joshua Reynolds, an old man and nearly blind, searched in vain for his favourite bird, and on the site of the Westminster (not Western) General Dispensary in Gerrard-street, Soho, stood the Turk’s Head, where met the most famous literary Club the world has ever known, Dr. Johnson at its head and Goldsmith admitted as a kind of poor relation. How many Londoners could say offhand which club-house it is of which the front is a 'combination of Sansovino’s Palazzo Cornaro and the Library of St. Mark’s at Venice'? It is (though, oddly enough, the book does not give it a name) the Army and Navy, at the south-west corner of St. James’s-square.

How many know that the statue of Charles I stands on the site of the original Charing Cross, or that the actual figure was buried for many years by the loyal brazier who had promised the Parliament to break it up? In walking down the Strand, now surely the most unpleasant street in London, we sigh for the days when it was a real river bank, lined on the south side by the palaces of nobles and bishops, with lawns sloping to the 'sweet Thames.' Spenser’s London is no more; but, in spite of modern improvements, the London of Hogarth and of Gay’s 'Trivia' is not so hard to realize as it should be. Fiction as well as Fact has peopled this district with immortals . . . .”

April 20, 2012

Literary lawyers

by DAVID HORSPOOL

I have never seen the point of reading an author because it's his anniversary, so I was rather surprised to discover today that it is 100 years since Bram Stoker's death, and it so happens that I am reading Dracula. Not rereading, I'm afraid (it has taken this long to get over a very deep-seated childhood fear of anything vampirish, which developed without a break into a deep-seated adult ennui at most vampire films and tv programmes).

I won't presume to pronounce on the book's virtues (though I will say that it's keeping me awake at night, so something's working), but the character of Jonathan Harker did prompt a thought about something else: sympathetically portrayed lawyers in literature. I suspect Harker isn't going to turn out all good (don't spoil it for me), but he's likeable enough at the beginning, fearlessly plunging deeper into Transylvania while everyone around him makes it achingly clear that it's a very bad idea. I like, too, that he seems genuinely preoccupied with seeking out local recipes (all big on paprika) to bring back to Mina. I realize he isn't the keenest of minds (cautious and risk-averse characters don't make for very good horror set-ups:"Don't go into the attic!" "No, I won't, it sounds absolutely terrifying."). But I can't help liking him.

Most literary lawyers are rather less heroic, less personable, more dried up, more like Mr Tulkinghorn. There are decent ones, but they tend to be advocates, barristers like Horace Rumpole or defence attorneys like Atticus Finch. Harker is a solicitor, a rather less glamorous type (his mission to Castle Dracula is to get some property documents signed; it's good that he has used his "Kodak" to take a picture of the place to show the Count). Solicitors are the sort of lawyers who account for the popularity of those coffee mugs that say, quoting Shakespeare, "Let's kill all the lawyers" -- mostly of course, owned by lawyers. I'm sure there are more examples of rounded, non-criminal lawyers in English letters, discounting those created by the likes of John Grisham or Scott Turow. But where should I look?

April 19, 2012

The TLS in Albert Square

By J. C.

The TLS has hit the screen again. Not the big screen this time. Our last outing in moviedom was as an eye-catching extra in the film Iris. Then, the TLS was a folded treasure idling around the Oxford house of Iris Murdoch and John Bayley. Our latest role was just last week, in an episode of the BBC1 drama EastEnders, in which all conversation seems to begin and end as shouting, with a brief interval for screaming in between. In the unlikely event of a victor ever emerging, the series will come to an end.

Cut to an Albert Square living room on April 12. During a lull in the bawling, Michael Moon is seated in an armchair, reading a magazine. He is interrupted in this un-EastEnder-ish activity by his fiancée, Janine, who presents him with a typed copy of their pre-nuptial agreement. Michael places the magazine on his lap while he speaks. The camera hovers at his shoulder. He has been reading . . . the TLS! Now, though, he must engage with Janine. Our contribution to the drama is over.We may not have said anything, but our appearance was pregnant with meaning.

Michael Moon is described to us by one keen watcher as both “an aesthete” and “a psychopath”. One of those explains why he is reading the TLS. The paper was open at a review of a book about Pope Benedict. The reviewer was our Religion editor Rupert Shortt. To semiologists among you, all is becoming clear: Michael wants the world to believe he is concerned with matters of the soul. He is . . . but not as he would have us think.

The Pynchonesque attention to detail on the part of the script writers does not end there. Some months ago, the refined Mr Moon was seen reading a different journal: the London Review of Books. No, we are not about to say that this demonstrates his essential wickedness. Yes, we are pleased to take it as proof that even psychopaths can change.

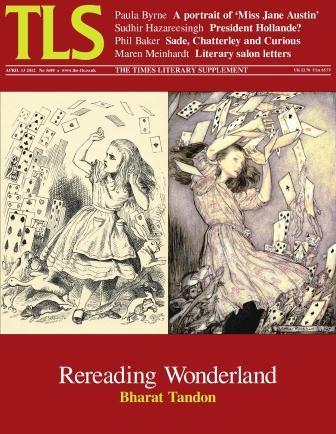

April 13, 2012

The rereading habits of the TLS staff

By Rozalind Dineen

In this week’s TLS, Bharat Tandon reviews two books on the subject of rereading. That’s right, rereading; as if the pile of books that we would like a chance to read even once isn’t large enough.

But rereading, as Tandon reminds us, can be one of life’s particularly rich experiences: it is where the narratives of novels and the narratives of our own lives “can converge meaningfully”. When we reread we remember where we were the first time, who we were and how we were. We realize how we reacted differently to a text when we were younger, or sicker, or holidaying or studying. “We may try to be semioticians . . . but autobiography is always breaking in.”

An office survey is one way to pass a Friday afternoon. So, do the TLS staff reread?

Some said no, only children and academics really reread. Others emerged as constant returners to favourite texts: Stalky & Co. by Rudyard Kipling, Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace. Poems are perfect for the rereader, book-length ones for the truly dedicated; “Madoc: A mystery” by Paul Muldoon and “The Oval Window” by J. H. Prynne were both mentioned. Graham Greene gets revisited, Money has been too. Siri Hustvedt’s What I Loved was the only book available to one staff member in a far off hotel on a rainy day, it turned out to seem more relevant and far more detailed the second time around.

One editor returned to a book he loved, Mikhail Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time, only to find it desperately disappointing. “It taught me not to go back to books I'd loved.” Another said she went back to D. H. Lawrence after a teenage infatuation, “and discovered that I hadn’t really ‘got’ it at all. The fourteen-year-old me had completely missed any hints of sadism, sexism or machismo – not to mention all that business about the yellow catkins, long danglers and little red flames.”

Julia Donaldson's The Gruffalo, The Gruffalo's Child, Stick Man, Tiddler, The Highway Rat, Tabby McTat and Zog all came up, having been read and read and reread once more (“but only once more and then lights out”) as bedtime stories. Asterix and The Wind in the Willows also featured, the TLS’s first reading of which was brilliantly wrong-headed (October 22, 1908): “The chief character is a mole, whom the reader plumps upon on the first page whitewashing his house. Here is an initial nut to crack; a mole whitewashing. No doubt moles like their abodes to be clean; but whitewashing? Are we very stupid? . . . However, let it pass . . . . We meet also a variety of animals whose foibles doubtless are borrowed from mankind, and so the book goes on until the end . . . . as a contribution to natural history the work is negligible.”

Some TLS editors read all the books that they review twice. Perhaps this anonymous reviewer of Kenneth Grahame did not. Or maybe he reread later in life and quietly changed his mind.

As rereading (just like its parent, reading) is an appetite that can never be satisfied, the follow-on question had to be, what would you reread in an ideal world? Proust, Dostoevsky, Jeffrey Archer. “Everything by William Gaddis, Underworld by Don DeLillo, One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Márquez (if I had some years of solitude in which to do so ho ho ho)”.

We welcome your rereading anecdotes below. It’s a way to pass a Friday afternoon.

April 6, 2012

John Arden and the humbling of the critics

In belated tribute to the playwright John Arden, who died last month, here's another word from the TLS archives (located in the vicinity of the basement labyrinth, obviously), from a review of a collection of three plays by the theatre critic Irving Wardle:

"The case of John Arden is one to make theatre critics realize the humble nature of their occupation. . . .

If ever the critical profession have banded together to thrust a dramatist upon the public, they have done so for Mr. Arden: in his cause they have journeyed to outlying repertory companies in Scotland and the West Country for Arden premiers on Tudor and medieval German themes, and they lose no occasion for proclaiming him as the most hard-working, original, technically well-equipped, and least cult-conscious dramatist to have appeared since the 1956 upheaval [when John Osborne's Look Back in Anger had its first performance]. Outside the universities, though (where Mr. Arden seems to get most of his performances), the campaign has done nothing to dent the public's indifference. Art theatre productions of his plays have been brief, and no commercial West End management has yet presented any of his work."

That was the view from 1965, when it was possible to write about reviewers and the public like that, and when the Royal Court had staged a sequence of Arden plays to impressively empty houses. Critical acclaim was no match for public indifference. Perhaps Arden's achievement in writing, with Margaretta D'Arcy, what is reputedly the longest play in English – The Non-Stop Connolly Show, which in performance is over a day long, and could be recommended, on the occasion of its first production, as "the cheapest doss in Dublin") – may be taken as an indication of his willingness to ignore the conventional principles of commercial success (in this case, that hoary old classic, "always leave them wanting more").

Arden certainly had a champion in the young John Russell Taylor, who praised him from time to time in the TLS, and, in his "guide to the new British drama", Anger and After (1962), applauded the Royal Court as "absolute right" to have supported Arden despite "hostility and plain indifference". Arden was, for Russell Taylor, the kind of writer who could improve on Goethe: the narrative of Ironhand, his reworking of Goetz von Berlichingen, is strong where the original is "rambling and disconnected"; where the original depicts Goetz's exploits as "uncomplicatedly heroic", Ironhand (a "lively, action-packed piece of theatre") is more complex and even-handed. Who could ignore that?

Well, you know who: anyone who doesn't want a dramatist "thrust" upon them, to adopt Wardle's unsavoury Shakespearean term.

If that's not enough to remind any current theatre critics of their "humble nature", here's a hopeful exercise in prophecy from the early 1960s – a vision of the theatrical future from Anger and After, as summarized in the TLS:

"Harold Pinter emerges as the likeliest hope for the future, with Alun Owen, Clive Exton and John Arden as the runners-up. John Osborne is somewhat summarily restricted to a future of turning out well-written plays for popular audiences. . . . Robert Bolt and Willis Hall are nowhere. It is good to see justice being done to David Campion, the most neglected of the new dramatists; and to Sydney Newman, the dominant influence on British television drama which, in some ways, has been the most important development of all."

You don't need me to say what's right and what's wrong with that picture, do you?

April 4, 2012

Re-reading Catcher in the Rye

By Michael Caines

Here's an early warning for you: in next week's TLS, Bharat Tandon reviews On Rereading by Patricia Meyer Spacks – a retired professor's "personal experiment" in revisiting everything from childhood favourites to "canonical works of literature she was supposed to have liked but didn't". Surely you can think of a few of those?

I'm reminded of a TLS review that mischievously began like this:

"Could it be that A Midsummer Night's Dream is not a very good play? It has three scarcely related actions — the bumpy course of young love, the difficulty (especially if you are an ignorant bumpkin) of staging a play, and a climate-changing stand-off between the King and Queen of the fairies. Its characters are walking contradictions. . . ."

Patricia Meyer Spacks has another supposed classic in her sights – The Catcher in the Rye.

"The Catcher in the Rye resembles Lucky Jim both in import and its early and later effects on me. A work that has never lacked an admiring audience, it had trade sales of 425,314 copies in 2010 alone, my editor tells me – along with who knows how many sales for high school and college courses. Salinger's death generated an outpouring of testimonials about how much the book had meant to individuals. As for me, I loved it when I first read it and taught it with enthusiasm at Wellesley. And I loathed it when I reread it."

There is no end to the loving or loathing of J. D. Salinger's novel, which seems to have an enduring power to divide, like literary Marmite. Some hate its style (Holden Caulfield's, really, as aped by the New York Times reviewer, James Stern). Others love Holden's view of the world. A lazy look online suggests that it's still all right with the kids but not with Page Plucker. The TLS said this:

"Mr. Salinger is well known in America for his short stories and has not achieved sufficient variety in this book for a full-length novel. The boy is really very touching; but the endless stream of blasphemy and obscenity in which he thinks, credible as it is, palls after the first chapter."

And ends on this delightful note:

"One would like to hear more of what his parents and teachers have to say about him."

But then a little later, another reviewer could refer to the book as "that most haunting novel of adolescence", and its influence (perhaps the influence of its popularity) could be detected in the work of other novelists.

You'll have to (at least) Google-read a couple of pages to see how Spacks puts her own differing reactions into the context of her life as a reader, re-reader and teacher, and makes more of them than just another contribution to the battle between the novel's admirers and detractors (the detractors should include anybody thinking of writing a novel themselves, apparently).

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers