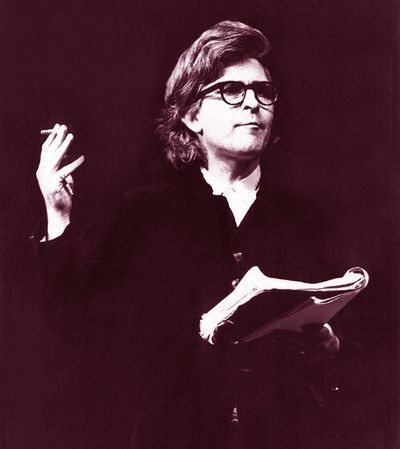

John Arden and the humbling of the critics

In belated tribute to the playwright John Arden, who died last month, here's another word from the TLS archives (located in the vicinity of the basement labyrinth, obviously), from a review of a collection of three plays by the theatre critic Irving Wardle:

"The case of John Arden is one to make theatre critics realize the humble nature of their occupation. . . .

If ever the critical profession have banded together to thrust a dramatist upon the public, they have done so for Mr. Arden: in his cause they have journeyed to outlying repertory companies in Scotland and the West Country for Arden premiers on Tudor and medieval German themes, and they lose no occasion for proclaiming him as the most hard-working, original, technically well-equipped, and least cult-conscious dramatist to have appeared since the 1956 upheaval [when John Osborne's Look Back in Anger had its first performance]. Outside the universities, though (where Mr. Arden seems to get most of his performances), the campaign has done nothing to dent the public's indifference. Art theatre productions of his plays have been brief, and no commercial West End management has yet presented any of his work."

That was the view from 1965, when it was possible to write about reviewers and the public like that, and when the Royal Court had staged a sequence of Arden plays to impressively empty houses. Critical acclaim was no match for public indifference. Perhaps Arden's achievement in writing, with Margaretta D'Arcy, what is reputedly the longest play in English – The Non-Stop Connolly Show, which in performance is over a day long, and could be recommended, on the occasion of its first production, as "the cheapest doss in Dublin") – may be taken as an indication of his willingness to ignore the conventional principles of commercial success (in this case, that hoary old classic, "always leave them wanting more").

Arden certainly had a champion in the young John Russell Taylor, who praised him from time to time in the TLS, and, in his "guide to the new British drama", Anger and After (1962), applauded the Royal Court as "absolute right" to have supported Arden despite "hostility and plain indifference". Arden was, for Russell Taylor, the kind of writer who could improve on Goethe: the narrative of Ironhand, his reworking of Goetz von Berlichingen, is strong where the original is "rambling and disconnected"; where the original depicts Goetz's exploits as "uncomplicatedly heroic", Ironhand (a "lively, action-packed piece of theatre") is more complex and even-handed. Who could ignore that?

Well, you know who: anyone who doesn't want a dramatist "thrust" upon them, to adopt Wardle's unsavoury Shakespearean term.

If that's not enough to remind any current theatre critics of their "humble nature", here's a hopeful exercise in prophecy from the early 1960s – a vision of the theatrical future from Anger and After, as summarized in the TLS:

"Harold Pinter emerges as the likeliest hope for the future, with Alun Owen, Clive Exton and John Arden as the runners-up. John Osborne is somewhat summarily restricted to a future of turning out well-written plays for popular audiences. . . . Robert Bolt and Willis Hall are nowhere. It is good to see justice being done to David Campion, the most neglected of the new dramatists; and to Sydney Newman, the dominant influence on British television drama which, in some ways, has been the most important development of all."

You don't need me to say what's right and what's wrong with that picture, do you?

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers