Peter Stothard's Blog, page 76

February 3, 2012

Domestic fictions

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

If you're a woman, and you write a novel about a family, there's a pretty good chance that it will be classed as "domestic fiction". Tessa Hadley, who was interviewed by the literary journalist Suzi Feay at Foyles bookshop in Charing Cross Road on Monday, finds this unhelpful: she said it seemed to suggest that her new collection of short stories, Married Love (the title is a playful allusion to Marie Stopes), was "all about baking". It is in parts, she said, but it's about much more than that – characters have jobs, for one thing.

Feay also interviewed Samantha Harvey, who has examined family relationships in the context of a novel of ideas – All Is Song – about a modern-day Socrates. When Feay asked "Why Socrates?", Harvey replied that she was fascinated by the outlook of somebody who embodied philosophy as an approach to life. How would you live, she wondered, if you had an obsessive compulsion to question everything, in fundamental ways? How would it conflict with the simple need we all have just to get through the day? Socrates is never actually mentioned in the book (the relevant character is called William); and Harvey said it doesn't matter if you don't recognize the biographical details she has borrowed – the military background, the late marriage, particular moral issues he struggled with, certain phrases and foibles . . . .

Harvey's first novel, The Wilderness (2009), was written from the point of view of a sixty-year-old male architect. She likes writing from a male perspective, she said, because she can get straight into fiction mode, whereas writing as a woman blurs the boundary between fiction and autobiography – she finds herself asking "What do women think?" in a flummoxed sort of way, as if she wasn't one.

Both authors observed how difficult ideas-heavy writing is: Hadley's novel London Train (2011), about a man and a woman who meet on the Cardiff to London line, was originally much longer, with conversations that were "argued through, and beyond through" and therefore "read dead". "I cut almost all of it", she told us. "All that was left were two little bits that shone." Harvey cut "ninety-seven per cent" of the philosophical content of All Is Song.

For Harvey and Hadley, writing is a compulsion. Harvey wanted to give it up, but she couldn't; it proved a necessary form of communication that also calmed her down, like a tranquillizer. Hadley persisted through the early stage when the whole enterprise felt mildly absurd ("Instead of doing proper things . . . you make up stories, badly") and through the notes from publishers that said things like "Your main character is too boring". When her writing did get published, she was rewarded, of course, with a new sense of identity: "Your deepest thinking about things gets its fulfilment", she said.

In the question and answer session afterwards a member of the audience remarked on how nicely designed the cover of Hadley's book is, and Hadley said that in the wrong hands it could have been made to scream "mum-lit", which apparently is "just like chick-lit, but grey". Perhaps, at this point, I should have raised the issue of domestic fiction again. As a category it masks variation and complexity, clearly – but why the does the phrase have a disparaging air?

Married Love and All Is Song will be reviewed in a future issue (or future issues) of the TLS.

February 1, 2012

How to talk to your literary agent

By Michael Caines

There are many wonders in this week's TLS – letters from Napoleon Bonaparte, for example, and the return of Yorkshire's prodigal son, David Hockney – but for authors troubled by literary agents, or at least literary agents with impertinent assistants, perhaps most wonderful of all is the prolific and self-possessed Georgette Heyer's demonstration (as quoted in Matthew Dennison's review of Jennifer Kloester's biography) of how to put such creatures in their place.

Observe how Heyer, the beloved author of Bath Tangle (romance) and Why Shoot a Butler? (target practice, Georgette?), among many others, replies to the lowly being who imagines that she need pay attention to what the reviewers say about her books:

"My dear good creature, do you really picture me with a pot of paste and a pair of scissors eagerly sticking press cuttings into an album? I'm thirty-three & I've been writing for thirteen years – no, sixteen years!"

There's more to the "Queen of Regency Romance" than a sharp eye for period detail, it would seem . . . .

January 31, 2012

The other Belle's Stratagem

#

By Michael Caines

The story goes – if I haven't muddled my theatrical anecdotes of the eighteenth century – that when Goldsmith decided he would call his new play She Stoops To Conquer, his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds suggested an alternative . . . .

The Belle's Stratagem. Sir Joshua was insistent about it, in (vaguely remembered) fact. If the play wasn't retitled according to his wishes, he would turn up on the opening night and heckle or hiss (I might have invented that alliterative threat; he probably threatened to "damn" the play).

In the event, Goldsmith stuck to his guns, and his allusion to Dryden: She Stoops To Conquer, "low" humour and all, turned out to be a great success; and a few years later, The Belle's Stratagem would actually be used by another playwright, Hannah Cowley.

Cowley's Belle's Stratagem was recently revived at the Southwark Playhouse, and I wrote then that I thought 2011 had been a good year for eighteenth-century drama (and that it didn't take much to make it a good year for eighteenth-century drama . . .).

But, as if I need to ask, what do I know? Now it's 2012, and it's Goldsmith's turn: She Stoops To Conquer opens tonight at the National Theatre. That's followed shortly by The Recruiting Officer by George Farquhar at the Donmar Warehouse. And there's even, for one night only, The Clandestine Marriage (1766) by David Garrick and George Colman the Elder in a semi-staged reading at Dr Johnson's House.

That's all good news, I think, but I have a particular interest in the Goldsmith play because I've had the privilege of working as one of the historical consultants for the NT's production, which meant, apart from anything else, sitting in on the first couple of days of rehearsal, seeing the model box, meeting the cast (as embedded, above), and losing my way backstage – so I have an idea about how much excellent work had already gone into the production before rehearsals even started.

January 25, 2012

Happy-go-lucky Edward Thomas

By Michael Caines

In this week's TLS, Paul Jarman reviews Matthew Hollis's Now All Roads Lead to France, which tells the story of Edward Thomas's last years, alongside the first volumes in the new Oxford edition of Thomas's writings – of his writings in prose, that is. Apparently the longest single work in those two volumes is a novel set in surburbia. Apart from a few mighty cognoscenti, who would have expected that of a countryman-poet?

Reading the novel now, with Thomas's ruralist reputation in mind, it's interesting to see how he reshapes, tantalisingly, the matter of his own life in South London. Thomas was born in Lambeth, and for many years his family lived at 61 Shelgate Road in Clapham. His parents moved a little further south, to Rusham Road, nearer Wandsworth Common, after Thomas moved out of town. So he knew the area well, and revisited it frequently.

Published in 1913, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans is only a "short novel", but, according to Guy Cuthbertson, one of the editors of the Oxford volumes under review, "it contains a great deal of Edward Thomas: . . . the book displays his interests, his talents, his reading, and many of his memories". Thomas himself described it as:

"a loose affair held together if at all by an oldish suburban home, half memory, half fancy, and a Welsh family (mostly memory) inhabiting it & collecting a number of men & boys including some I knew when I was from ten to fifteen."

Seeing this loose scheme as an opportunity to "use all memories up to the age of 20", Thomas therefore "indulged himself freely".

The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans begins by announcing that it is a story of Balham in South London, and of "a family dwelling in Balham who were more Welsh than Balhamitish"; and at the heart of the story is Abercorran House, a suburban paradise of a place, where the Morgans live, named after a small town in Carmarthenshire (Abercorran being an old name for the real Welsh town of Laugharne, where Dylan Thomas lived for the last few years of his life and wrote Under Milk Wood). Apparently, it's Laugharne rather than London where you'll find an Abercorran House today.

Although the novel's suburban Abercorran House is gone by the time the story begins, the street where it stood (now "straight, flat, symmetrically lined on both sides by four-bedroomed houses in pairs") has inherited the name, and the "three-acre field" that was its garden has likewise passed on its old nickname, The Wilderness, to Wilderness Street. No. 23 Wilderness Street "probably has the honour and misfortune to stand in the pond's place":

"I can understand people cutting down trees – it is trade and brings profit – but not draining a pond in such a garden . . . and taking all its carp home to fry in the same fat as bloaters, all for the sake of building a house that might just as well have been anywhere else or nowhere at all."

Another survival gives the narrator greater satisfaction: Ann Lewis, the Morgans' old servant, lives at No. 21 Wilderness Street; she approves of her current employer because he at least has the decency to be Welsh.

Reviewing the novel in November 20, 1913, alongside Saki's latest (When William Came) and other works of lesser note, the TLS observed that The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans made for "rather patchy reading" but had "undeniable artistic merits", not least in its depiction of the "dark and hugger-mugger rooms" of the house, its environs and inhabitants – of the "yard with men and dogs sunning themselves in it; the fish-pond; Jessie's singing, the doves, Mr. Morgan's cigar . . . the various hangers-on, such as Mr. Torrance, the bookseller's hack, Mr. Stodham, the clerk, and Aurelius, the superfluous man; the literary talk, the quotation from the poets, and the tales of folklore and of Welsh worthies . . . ."Such reminiscences struck the reviewer, who recognized the narrator of the novel as Thomas's alter ego, as exceptional: "There are not many who remember their boyish day-dreams so well as to set them down faithfully on paper years afterwards".

Thinking of those regularly anthologized poems of his, about the countryside (I admit a grave weakness for "Haymaking", with its bow-and-arrow flight into the past), I'm struck by how lyrically Thomas can depict suburbia. The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans fully acknowledges the mysterious pleasure of wandering around the city:

"Sometimes in our rare London travels we had a glimpse of a side street, a row of silent houses all combined as it were into one gray palace, a dark doorway, a gorgeous window, a surprising man disappearing. . . . We looked, and though we never said so, we believed that we alone had seen these things, that they had never been seen before. . . . Some of the very quiet, apparently uninhabited courts . . . made us feel that corners of London had been deserted and forgotten, that anyone could hide away there, living in secrecy as in a grave."

Perhaps the spirit of these words is not so different from that of a poem written a little later, in the year Thomas enlisted in the Artists' Rifles, "Good-night", in which – for all that "Thrushes and blackbirds sing in the gardens of the town / In vain: the noise of man, beast, and machine prevails" – the poet can "seem a king" as he walks through the "unfamiliar streets":

The friendless town is friendly; homeless, I am not lost;

Though I know none of these doors, and meet but strangers' eyes.

Only the refracted Happy-Go-Lucky sentiment, if that is what it is in "Good-night", ends in wartime poignancy:

Never again, perhaps, after tomorrow, shall

I see these homely streets, these church windows alight,

Not a man or woman or child among them all:

But it is All Friends' Night, a traveller's good night.

Studies of Edward Thomas can't quite agree where exactly Abercorran House is meant to be – one suggests it's "on the edge of Hammersmith", which could be facetiously translated as "in the Thames" – or indeed if it was meant to be anywhere. Thomas was being deliberately discreet about its location, we're told; his correspondence certainly shows that he felt constrained to be a little more vague than he would have liked.

Then again, from a "mapping writing" point of view (of which more at a later date, I hope), it's interesting to note that Thomas also considered giving the book a subtitle, "A True Story of Balham", and a preface emphasizing that the novel was based in reality. As it is, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans gives directions to Abercorran Street from where the tram stops ("up Harrington Road . . . the second turning on the right"), and mentions various house names: No. 23 is called "LYNDHURST", and the houses on the street running up to Abercorran House are called The Elms, Orchard Lea, Brockenhurst and Cadelent Gate.

Are those clues enough to direct any would-be literary sleuths or future biographers to some strand of leafy suburbia where it will turn out that red-brick, semi-detached houses ("four-bedroomed houses in pairs"), carrying similar names (if not the same names), still stand in straight lines, between Clapham Common and Wandsworth Common, Wandsworth Common and Tooting Common? Or would that be to miss the point of the "beautiful fantastic geography" of this countryman-poet's London novel?

With thanks to Paul Jarman.

January 21, 2012

Folio turns 40

BY ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Folio turns forty this year. For all lovers of French literature this should be a cause for celebration, as this imprint of the publishers Gallimard could be said to be the French equivalent of our Penguin paperbacks. Folio's competition in the paperback market has come principally from Flammarion and of course Livre de Poche, the distinctive collection published by several different firms. Livre de Poche still has an evocative post-war charm, but its volumes have not physically aged well: all too many of my Livres de Poche, from La Princesse de Clèves to Le Silence de la mer, have cracked spines and yellowing pages that threaten to fall apart on contact, like some medieval parchment (probably not helped by the fact that I picked up quite a few of them second-hand). Folios, with their white backgrounds, solid spines, excellent cover illustrations and reader-friendly type, have always been a pleasure to handle and to read – the perfect paperback in fact.

Which is not something I've often felt about Flammarion. I have on my shelves quite a few Flammarions – they must have been cheaper than Folios – but, I wonder, would I have enjoyed reading those books more if I'd possessed the Folio edition? When I embarked on Laclos's Liaisons dangereuses, Flammarion edition, I struggled at first with its characteristic dense type and narrow margins. I switched to the Folio edition (over a hundred pages longer, and with a Preface by André Malraux), and breezed through it.

In the case of Rousseau's Confessions, I see that I have the first volume in Flammarion, while for the second one I knowingly went for the Folio edition. I clearly took no chances with Stendhal's Le Rouge et le Noir as I have two copies: the Folio with a Preface by Claude Roy (700pp) and the Livre de Poche, with a short Introduction by Roger Nimier (512pp).

Further along my shelf is a Flammarion edition of Théophile Gautier's Voyage en Espagne which I bought when I spent a year at the University of Aix-en-Provence (from dreary London to balmy Aix). As an "auditeur libre" I was free to attend whichever course of lecture/seminars I fancied, one of these being the appealing-sounding "Flâneries esthétiques" (rather more imaginative than the monolithic "Racine" or "Camus" I had been offered at uni back in Blighty). First on the reading list was Gautier, but I regret to say it remains unread by me to this day, partly on account of its unattractive layout. I attended that course long enough to hear my fellow French students being berated by the prof for poor style, spelling and punctuation (never mind the content) as she handed them back back their first essays (being a foreign student I was excused from having to do any work at all).

Folio saw me through my university special paper on André Gide: I have half a shelf of his books in Folio and I see that my copy of the autobiography Si le Grain ne meurt is thick with marginal "NBs", at one point eight in seven pages: how helpful was I really being to myself with such undiscriminating marginalia?

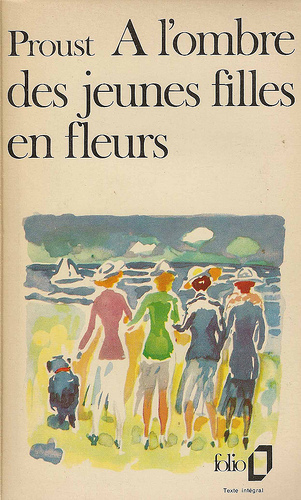

The most intense and exhilarating reading experience I've had was in Folio: staying up half the night three days running to read Proust's A l'Ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs before moving straight on to Le Côté de Guermantes. I like the fact that my Folio edition of Proust has no introduction, preface or notes – just the text. And there is the added pleasure of the cover illustrations by Kees Van Dongen. Frustratingly my copy of Albertine disparue doesn't have a Van Dongen cover, as I lost it and had to replace it; I therefore don't have "the set".

Aside from my magically unannotated Proust I have a set of Folio Camus books which are also, surprisingly, without any critical material, and I don't mind. But the editorial policy seems to have been random: Michel Tournier's masterpiece Le Roi des aulnes comes with a "Postface" (postscript) by Philippe de Monès. Who is Philippe de Monès I wonder? The same author's Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique also has a (long) "Postface", by Gilles Deleuze this time. I had no idea who Gilles Deleuze was either when I read that novel. I wonder if I ever read his postscript.

To read the TLS review of My Fantoms by Théophile Gautier from 1976, click here

January 19, 2012

The trouble with productivity

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

Can you be productive by not being productive? Are there artistic possibilities in exhaustion, failure and laziness? Those were among the questions posed at the ICA last week during a discussion between the writer and critic Laura McLean-Ferris, the curator Paul Pieroni, and the writer and philosopher Lars Iyer (all of whom are unusually productive, we audience members couldn't help noticing).

McLean-Ferris opened with reference to a number of articles written a few years ago when the art market was at an "overblown" level: Dan Fox observed in Frieze Magazine (of which he is associate editor) that the art world had developed into "a high-turnover, high-visibility international activity that everyone wants a slice of", and expressed an uneasiness about galleries' sleek corporate architecture and vague but authoritative-sounding art-speak, which he suspected to be somewhat at odds with the ways in which artists actually work. In a piece entitled "I Can, I Can't, Who Cares", the critic and curator Jan Verwoert, troubled by the relentless pressure on creative types to "perform", looked around for interesting and amusing examples of "unwillingness, non-compliance, uncooperativeness, reluctance or non-alignment".

One example is the work of the Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović, whose photographic series "The Artist at Work" (1978) shows him lying in bed. Stilinović is the author of a manifesto, "In Praise of Laziness" (1993), in which he describes laziness as "the absence of movement and thought, dumb time – total amnesia. It is also indifference, staring at nothing, non-activity, impotence. It is sheer stupidity, a time of pain, futile concentration". Those "virtues of laziness" are important factors in art, he says: "Knowing about laziness is not enough; it must be practised and perfected".

McLean-Ferris pointed out that Herman Melville's Bartleby the Scrivener – who discombobulates his Wall Street colleagues with the refrain "I would prefer not to" – has become a sort of model for non-compliance among artists. Étienne Chambaud produced a neon sign that reads "I would prefer not to too" (2007), which never gets switched on. Pilvi Takala spent a month in the marketing department of the accountancy firm Deloitte, where she filmed herself doing nothing all day for her installation The Trainee (2008). Only a few people knew that she was not an ordinary worker. As it says on Takala's website: "these acts, or rather the absence of visible action, slowly make the atmosphere around the trainee unbearable . . . . What provokes people in non-doing, alongside strangeness, is the element of resistance. The non-doing person isn't committed to any activity, so they have the potential for anything".

Paul Pieroni was keen in his talk to "recalibrate ideas about how we might understand procrastination". While acknowledging that it can be straightforwardly evasive – he confessed that when he was supposed to be preparing for his ICA appearance he went out and bought a carbon monoxide detector, having created "a ridiculous context where I might die" – he said that procrastinatory "counter-activity" can be important in art production, "especially when we're not sure what the priorities of our actions are".

Counter-activity can have value even if the original goal is discarded entirely, he said: his friend Mike Harte, who at one time aspired to be an artist but always seemed to find something else to do (sitting about, karaoke, eating Choc Dips – we were treated to a little slide show), used to write letters full of trivia, newspaper cuttings and "general nonsense" to his friend Jamie Shovlin, who was then studying at the Royal College of Art. Shovlin kept the letters and made them into an art project of his own, Mike Harte – Make Art, which was commissioned by the collective art collection V22. Pieroni has lately been researching what he calls the effluvia of office work – which include humorous pictures and signs such as the ones on this page (other slogans include "A tidy desk is a sign of a sick mind") – for the exhibition Xeroxlore, which opens tomorrow, January 20, at SPACE.

Lars Iyer's subject was the common view of consumers versus producers: consumers are suggestible and easily manipulable, while producers are in control, in charge. He finds the modern notion of the producer problematic: in an age of neoliberal capitalism, he said, to be a producer is to be a capitalist entrepreneur; and very often what producers are marketing – through social media, for example – are not artworks, but themselves. The ICA audience, a large, mostly young crowd (Mike Harte was there – I spotted him in the bar afterwards), asked some interesting questions in relation to this; McLean-Ferris answered one about productivity and internet use with the comment that people who upload a lot of material tend to be particular kinds of people, who can set the agenda in ways that may not be obvious.

Iyer suggested in a recent article in the White Review that great literature was over, and that modern writers were sullied by their active involvement with the marketplace. At the ICA he told us that if writing is to be successful today, it should respond "to the ways in which we arse about when no one's watching us". Iyer's compulsively readable, funny and touching novel Spurious (2011) started as an attempt, in the form of a blog, to answer a serious philosophical question. "What I found myself doing instead", he told us, "was recording the stupid conversations I'd had with a friend of mine".

January 17, 2012

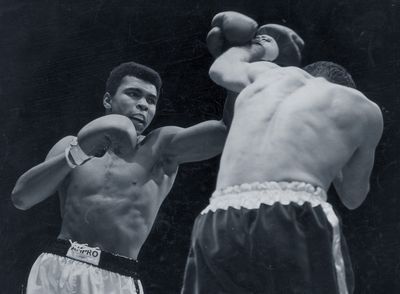

Muhammad Ali and the TLS

BY DAVID HORSPOOL

As luck would have it, I missed the interview, but my wife told me there was a Cambridge Professor on the radio a few mornings ago discussing his new project of collecting coincidences. Here's one for him: Muhammad Ali and the TLS share a birthday. The TLS began life exactly 110 years ago, on January 17 1902, with the fateful announcement that "During the Parliamentary Session LITERARY SUPPLEMENTS to "THE TIMES" will appear as often as may be necessary in order to keep abreast with the more important publications of the day".

Forty years later, on January 17, 1942 (coincidentally, a Friday, hence a TLS day, as in 1902), Cassius Clay was born in Louisville Kentucky. The TLS was understandably concentrating on "important publications" on the only subject of note, the War.

Now you may say that this is hardly a coincidence, plenty of famous people must have been born on January 17 (and so they were: Clyde Walcott, Eartha Kitt, Rock Hudson), but here's the spooky part. I am, among other things, the commissioning editor for Sport on the TLS, and have always taken a great (and yes, unenlightened) interest in boxing in general and Ali in particular. So I was very pleased when my brother kindly promised to buy as a birthday present a print by the great Sunday Times and Observer sports photographer Chris Smith, of Ali, from an exhibition he had happened upon. I was lucky enough to meet the photographer and the gallerist (who -- coincidentally -- owns a sandwich shop near the TLS office which supplies our Editor with his lunch every day) and chose a photograph, which would need to be printed up for me.

And when did I get the call to say the print (not shown above) was ready? Today, on Ali's birthday, which fact neither Mr Smith nor the gallerist had noticed (in case you think they were trying to give me a special service).

The final piece of the jigsaw occurred to me only after I looked again at the photograph I had chosen as my birthday present. I was born on January 7 1971 (two days after Ali's first great defeated opponent, Sonny Liston, was found dead in Las Vegas), and quite by chance the photograph I had picked showed Ali training for his first comeback fight, the "Fight of the Century" against Joe Frazier -- in January 1971.

Now as any Cambridge Professor could tell you, none of this means anything, but I wonder whether such exact fits, near misses, or odd chimes are one way that we identify with things with which we might otherwise feel little connection. Or else they merely reinforce the sense that we are deeply connected to something for which we already feel some affinity.

I didn't think that anything could make the production of Jez Butterworth's play Jerusalem, which I was lucky enough to squeeze in to last Friday, strike me more powerfully as it reached its climax. That was before one of the characters put on a record, and the theatre filled with the sound of Sandy Denny singing "Who Knows Where the Time Goes", a song I had just finished listening to on my MP3 player moments before I entered the theatre. Sandy Denny was in Fairport Convention, whose album Unhalfbricking has on its cover a photograph of the group outside Denny's parents' house. You can see the church spire. I recognized it recently. It was the church at the end of my street when I was a boy in Wimbledon. Is someone trying to tell me something?

January 16, 2012

Who's Who . . . in Milan

By THEA LENARDUZZI

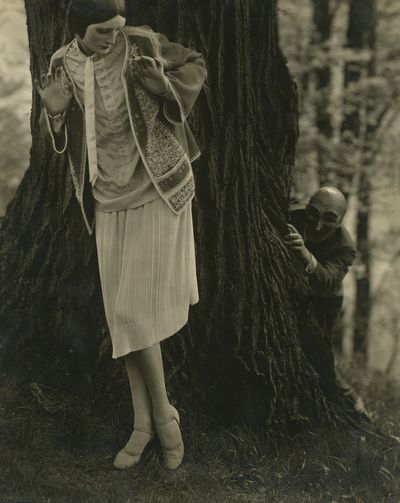

1353. Edward Steichen, Marion Morehouse wearing fashion by Tappé ; masks by the Polish illustrator W. T. Benda, 1926 © 1926 Condé Nast Publications, New York.

While Michael Caines was in the National Portrait Gallery, wondering if he was looking at whom he thought he was looking at and, indeed, who had painted the portrait of the unknown figure, I knew exactly who I was looking at: Greta Garbo, Winston Churchill, Walt Disney, Shirley Temple, Charlie Chaplin, Lee Miller, Katharine Hepburn and many more in one small room in Milan. The photographs are part of an exhibition of Edward Steichen's portraiture work at the Galleria Carla Sozzani at 10 Corso Como, spanning the years 1923–38, when he was chief photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair.

By the time of his appointment, Steichen was already a painter and photographer of global renown. Influenced by modernists such as Matisse and Duchamp, whose work Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz had exhibited in their "Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession" in New York (founded in 1905, and later known coolly as "291"), he accepted a dare by the French magazine publisher and photographer Lucien Vogel to elevate garments to the highest echelons of modern art. The gowns were designed by Paul Poiret, the Picasso of couture, and Steichen's photographs of them appeared in the April 1911 issue of Vogel's Art et Décoration, marking the beginning of a new movement in fashion photography: clothes could be expressions of form – part of an artistic vision or manifesto – rather than merely objects for sale. Without Steichen, would we have had Robert Mapplethorpe, Annie Leibovitz and Bruce Weber?

Steichen accepted the Condé Nast job, however, on the basis that making beautiful photographs had a strong use value – "I wanted to work with business, like an engineer". He photographed actors, models, statesmen, sports stars and dancers in highly theatrical poses. Noël Coward, concealed by shadows from the neck down, smokes a cigarette; behind him, atop a vertiginous staircase, is a cat's proud silhouette. It was taken in 1932, the same year that his play Design for Living premiered in New York. The play's representations of bisexuality and a ménage à trois were so risqué that Coward knew the censor would not allow it on a London stage.

Narratives in Steichen's photographs were strong, often dark and reflexive: the model Marion Morehouse peers cautiously round a tree while the designer and illustrator Władysław Teodor "W.T." Benda squats in a grotesque mask of his own design. Like Steichen himself, Benda is stalking the elusive "American Girl". (A few years later, e. e. cummings caught Morehouse for himself.)

The Condé Nast years coincided for the most part with the Great Depression, but, while the economy declined, high glamour persisted – even when, in 1936, Vanity Fair ceased to be published separately and was incorporated as a supplement of Vogue. Though Vanity Fair's readership had continued to grow in the years before it closed, the readers weren't buying, just looking, and advertisers withdrew.

There may be no more fitting location for this retrospective than 10 Corso Como. Founded in 1990 by Carla Sozzani, a former journalist and fashion editor, the building was designed as a sort of architectural magazine. I browsed its fashion concessions (just looking, sadly), peoplewatched in the cafe/restaurant and flicked through its bookshop (I spent a while here, excitedly pointing out books by TLS contributors to my, less excited, companion), on my way up to the gallery. There, despite the bleakest economic climate since the Second World War, Milan preserves an inviolate space for glamour. And – austerity be damned – this "gla-mooor" (pronounced the Italian way) is free.

January 13, 2012

Imagined lives out of false portraits

Copyright: © National Portrait Gallery, London

NPG 1173: Unknown woman, formerly known as Margaret Tudor (1489-1541)

By an unknown artist

In the wake of reports of Brontë portraits selling well and Austen portraits causing controversy (follow that link for comments on the portrait recently championed by Paula Byrne on BBC2, from Claire Harman and others, and a couple more here), here's a question posed by the National Portrait Gallery: what do you do with all the discredited images of princes, aristocrats, writers? Such as the one above, of an unknown woman, formerly known as Mary, Queen of Scots.

Visiting an art gallery, as the curator Tarnya Cooper observes, almost inevitably involves an encounter with the "unknown" – with unknown men or women, faces once thought interesting or important enough to be worth recording (or kindly misrepresenting, you might say). Early collectors tended to be "overzealous" in their identification and labelling of portraits; no wonder the NPG's postbag now "bulges with requests to help identify the people depicted in historic portraits".

The strength of later doubts is obvious from the consistency of the adverbs on display in Room 33, where Imagined Lives: Portraits of unknown people is now on display, following an earlier version of this small exhibition at Montacute House in Somerset:

"Probably Sir Robert Dudley (1574–1649), formerly known as Sir Thomas Overbury (1581–1613)."

"Unknown man, possibly William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585–1649)."

"Unknown man, fomerly known as James Scott, Duke of Monmouth and Buccleuch (1649–85)."

And of the artists responsible for these portraits, only two can be tentatively identified. . . .

Unless you're the lucky art historian who turns up a letter or some other piece of evidence that can transform a "possibly" into a "definitely", there's little choice but to carry on warily speculating – something that Imagined Lives turns to its advantage in turning to a band of well-known writers, including John Banville, Tracy Chevalier, Terry Pratchett and Minette Walters, and seeing what they can do with the Unknown. The writers' responses may be seen both in the gallery, and in the form of a short book.

The results are like the outcome of a (slightly posh) writers' group exercise. Some contributors opt for the route of the sitter speaking for him or herself (by letter or diary), others adopt a curatorial tone ("The commissioning of the portrait reflects his assurance and status as a composer"). Julian Fellowes has re-identified the woman who used to be known as Margaret Tudor (above) as Blanche Vavasour, Lady Marchmont (1497–1558). "Dressed in widow's weeds, she wears a downcast look as well as a distinctive brooch. . . ." Or there's "False Mary", now shown by Alexander McCall Smith to be useful to the real one, Mary, Queen of Scots:

"After the slaughter of her Italian secretary, David Rizzio . . . she formed the view that she needed to employ a body double. This device was later to be used by a variety of shady twentieth-century dictators . . . ."

Copyright: © National Portrait Gallery, London

NPG 96: Unknown woman, formerly known as Mary, Queen of Scots (154287)

Unknown artist c.1570

Of course, if you think can do better than that, the NPG would like to hear from you: there's a monthly competition for aspiring practitioners of this particular form of ekphrasis. . . .

January 9, 2012

Gerhard Richter – The sublime on a postcard

BY MAREN MEINHARDT

There are many ways to deal with the succession of excellent, once-in-a-lifetime art exhibitions London seems to throw up all the time. One approach is to form a firm intention of going, congratulate oneself on said intention, and live smugly up until the point where it becomes clear that the exhibition has come to an end some months ago.

I'd been doing quite well with this technique, and Gerhard Richter's great retrospective, Panorama, at Tate Modern, was all set to become the latest event that had got away. Until unexpectedly a friend, who moreover possessed one of those lovely membership cards, swept me up almost at the eleventh hour.

One might have expected interest to have ebbed a bit by the time of the closing weekend, but a truly astonishing queue made it clear that this wasn't the case at all. Nor would the magic membership card allow us to queue jump.

It's tempting to wonder what aspect of Richter's work it is that attracts such numbers of people. He can hardly be accused of catering to any one particular taste. His range is so very broad, that even within the different rooms, where paintings have been grouped into periods, there is still great diversity.

There are the artworks called things such as "Grey", or "Mirror", which are just that, and, which never fail to invoke a mild sense of impatience.

But then among cloud pictures and sea scapes, beautiful but stern with a sparse palette, an astonishing blur of colour stands out: a version of Titian's Venetian Annunciation. The painting, a blurred impression of the original, represents, so the exhibition notes explain, a comment on the fact that it was "impossible to paint like Titian today, and that the 'beautiful culture' of Old Master painting was irretrievable". In an interview (with Michele Leight, in the City Review), Richter had explained, disarmingly, that he had copied the painting from a postcard, "simply because I liked it so much and thought I'd like to have that for myself. To start with I only meant to make a copy, so that I could have a beautiful painting at home and with it a piece of that period, all that potential beauty and sublimity."

Is it being German that makes it difficult to resist the dark pull of the room with the Baader-Meinhof pictures for long? Craig Raine, who reviewed the exhibition for the TLS, remarked that the "Baader-Meinhof pictures inevitably attract ideological inflation, even though Richter is a pains to repulse it".

I, too, had been wondering about the place of ideology in those pictures. In the past, Richter has made clear his opinion that ideology is best avoided. But the title of the monumental canvas showing Andreas Baader lying dead on the floor leaves does leave some room for doubt. In the official, and widely accepted version, Baader committed suicide; the English title of the painting "Man Shot Down" seems to suggest otherwise; the German "Erschossener" (shot person) is less controversial.

Of the triple portrait of Ulrike Meinhof, Raine describes how "in Richter's version, it is gradually, successively, eroded. Eyebrow, eyelid, open mouth blur into vagueness."

Richter does not glorify, nor criticize, and if one is looking for clarity, his work is not the place to search for it. The Baader-Meinhof story looms over the German psyche, just as monumental and shocking as Richter's portraits. His pictures represent this, but they don't explain.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers