Peter Stothard's Blog, page 79

November 18, 2011

Charles Dickens – enough already?

By MICHAEL CAINES

In this week's TLS (and online, too), Dinah Birch's review of two new books about Charles Dickens begins with a warning for the coming year: Dickens mania is about to be unleashed; Claire Tomalin's full biography and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's account of Dickens's early years are just the literary tip of a cultural iceberg. There will be "exhibitions, debates, documentaries, theatrical performances, public readings, and television and radio programmes. Films will include a major new Great Expectations. In Houston, there is to be a half-marathon especially for Dickens enthusiasts. No one with a taste for history, books, public events, or dressing up need feel left out".

If you know anybody who intends to honour Dickens's bicentenary by running around Texas, let us know.

For armchair Dickensians (possibly a more numerous breed), meanwhile, there is already a great swell of publication to see in the Year of Dickens. For example:

Aiming for the Dickensian coffee table, an enterprising New York publisher, Sterling Signature, has printed an abridgement of John Forster's Life of his friend – which was already an unusual book before they "added images throughout to complement the text" because Forster is sometimes said to be the inspiration for the pompous Podsnap in Our Mutual Friend. "Mr Podsnap was well to do, and stood very high in Mr Podsnap's opinion." Despite this unflattering portrait and other differences of opinion, as the editor of this illustrated edition notes, "the strength of the underlying relationship persisted" until the end.

Michael Allen's book Charles Dickens and the Blacking Factory, in fact, opens with a reminder that the voices of Forster and Dickens merge in the Life's account of Dickens's infamous childhood sufferings: "if Dickens chose to omit particular events or people from his narrative, or to adjust their impact and influence, then we are entirely in his hands – there has been nobody to challenge him".

Cambridge University Press have produced a facsimile of the manuscript of Great Expectations (which the author had presented to another friend, Chauncy Hare Townshend). Worth Press have published Charles Dickens: A celebration of his life and work by Charles Mosley (which covers the characters in his novels in such detail that they require a separate index).

More pocked-sized reissues come in the form of Dickens's Life of Our Lord ("written especially for his children") and The Genius of Dickens (originally, more flatteringly titled The Intelligent Person's Guide to Dickens) by Michael Slater. Then there are two books which share a title, bar a possessive "s": Dickens's Women by Anne Isba and Dickens' Women by Miriam Margolyes and Sonia Fraser. And earlier this year, Peter Rowland incorporated his suggestions about the onomastic origins of Fagin, first published in the TLS back in January, into Dickensian Digressions: The hunter, the haunter and the haunted.

That's quite enough for now, surely. Of the books, at least.

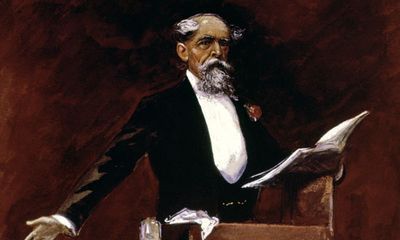

Anyone for Thackeray?

November 15, 2011

Humanities in the dock

No one has ever said that Archias was a great poet, not even his poetry student, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who in 62 BC was defending his teacher before a court that we might recognise today as an immigration tribunal.

Archias was a Greek poet from Syria whose job was to flatter Roman politicians. Cicero's hope was that, in return for his efforts to secure citizenship for Archias, he too, like mighty generals and dictators, would be flattered in a few memorable poems.

Cicero's understanding with Archias was a typical grubby little bargain of the time. The deal might have been forgotten entirely — except for one of those satisfying curiosities of history in which Cicero's short speech, Pro Archia, probably the least well known of all the great speeches in front of me now in the Folio Society's spectacular new edition, is the one that has played the greatest part in our still wanting to read any of them.

The Folio Cicero sits satisfyingly on the desk this morning, pale purple and with admonitory illustrations, both pertinent and elegant, by the artist, Tom Phillips.

Why read Cicero in the twenty first century? Why read any author who wrote in Latin or wanted to be written about in Greek? These are questions that book buyers can answer for themselves but universities must answer today against a mass of populist abuse and misunderstanding.

Classicists are increasingly tempted to defend themselves on utilitarian grounds — the claim that they train minds for hedge funds and our international leadership in dictionaries.

For much longer they have defended their investment of time and effort on Greeks and Romans with some version of the claim that there exists a connection, a common bond between all the arts that pertain to humane existence, omnes artes, quae ad humanitatem pertinent.

Those six words were Cicero's own, taken from the Pro Archia, spoken after he had begged the judges' permission to speak in Archias's defence a little more freely than an immigration dispute might commonly justify.

Cicero's subject was to be the study of humanity and literature itself, de studiis humanitatis ac litterarum. His case was that the life and work of Archias was a coherent benefit for civilised mankind, for young and old, in good times and in bad, at home and abroad.

This added justification, the defence of a poet's pertinence to politics and law, the unity of education, relaxation and moral example in a single ideal of humanity, became both devastating and decisive.

The scholar who first moved the ancient defence of Archias into the modern mind was Petrarch. On a student tour of northern Europe in 1333, he rediscovered the text in Liege, copied it out in saffron-yellow ink (embarrassingly for the young man this was the only colour he could buy in a 'fine but uncivilized town') and encouraged all his friends to copy it themselves and circulate it too.

The young Petrarch was chafing at his own legal studies; he enthusiastically recognised the path towards a coherent idea of humanities that would eventually unite grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history and moral philosophy into a single course of study

Cicero was central to all of these individual arts; but much more important was his part, through the Pro Archia, in bringing them together.

And he never even got his poem as a reward. When the time came for Cicero to need some flattering verses on his year as consul, he had to write them, famously badly, himself.

November 14, 2011

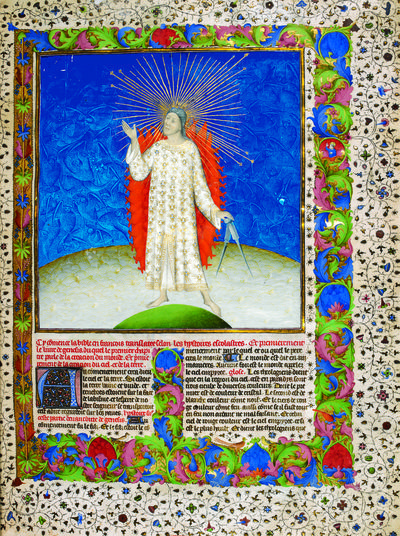

Kingship illuminated

Among other things, Royal Manuscripts: The genius of illumination, a new exhibition that opened at the British Library last week, reveals how fond medieval monarchs were of seeing themselves illuminated.

The image above of Henry VIII shows him usurping King David's throne, in a Psalter made for his personal use (that's Henry's handwriting in the margin, apparently). In this respect, although this illuminated manuscript dates from the middle of the sixteenth century, it is consistent with the fourteenth-century copy of Le Songe du Vergier (The Dream of the Orchard) also on display in this exhibition, which was made for Charles V of France: Charles duly appears at the beginning of the book, arbitrating in a debate between representatives of secular power to his left and those of spiritual power to his right. A border of trees suggests the orchard side of things, while a sleeping figure at the bottom of the picture shows that the debate is a writer's dream. The significance of the rabbits emerging from burrows is not quite so clear.

There is an earlier work, however, a genealogical chronicle of English kings unfurled in another display case (it's a parchment roll rather than a codex), in which the rabbits may have a symbolic reason for loitering around the Norman family tree: they are there, it has been suggested, to represent the Norman line's fecundity. It was a dynasty that bred like rabbits. The appropriate result, of course, in a circle towards the bottom of the scroll, is "William bastard" – ie, William the Conqueror.

(Or perhaps it has more to do with the Normans' introduction of the farming of rabbits, or "coneys", to Britain, first recorded in the twelfth century, on Drake's island in Plymouth Sound. . . .)

The British Library invites comments on these images and many more, in its facebook albums (nine people, at the time of writing, "like" the Henry VIII psalter; "Not very flattering of the king", the BL itself loyally remarks). Smartphones can be treated to an app that includes videos and plenty of images. If you can't make it to the exhibition itself – which will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS – here at least are two ways of viewing some of the earliest and most important acquisitions of the British Museum in the 1750s, when George II donated what became known as the "Old Royal Library", including about 1,200 decorated manuscripts, to the then-new institution. So while God wielding his world-creating compass "against a background of red and blue angels" (as the curators put it in an introductory guide to the subject), Brutus and his brother ticking off a queue of Roman ladies for dressing sumptuously (as seen by the makers of a lavish two-volume work made to order for Edward IV, that is), and Alexander the Great, backed up by his entire army, warding off a coalition of hostile dragons may seem to be diverse images, the exhibition that brings them together in public has been a long time in the making, you might say.

November 12, 2011

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 6

BY J. C.

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part VI. The "Back to Basics" tour. That rough crucifix we fashioned out of old Penguins bought from the Archive Bookstore must be working. The vampiric virus of Christmas "humour" books with titles of the Do Ants Have Arseholes variety appears to be shrinking in its coffin. There are fewer than ever this year.

Still, the hebdomadal legwork must go on. The number of secondhand bookshops on Charing Cross Road has dwindled in recent years, but three good ones remain, almost side by side on a stretch near Leicester Square: Any Amount of Books (to which we will return), Henry Pordes and Quinto. The last is, in fact, two shops: a posh antiquarian affair upstairs (trading as Francis Edwards), with Quinto in the basement. Here, the stock is changed regularly, and most items are under £5. It was to the lower depths that we gravitated on a wet November afternoon.

No modern literary journal has attracted as much opprobrium as Encounter. The title need only be uttered or written, for the inevitable pendant phrase to follow: "funded by the CIA". The sponsoring body was, in fact, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and early issues state the connection explicitly on the contents page, with the happy assurance that "The views expressed in Encounter are to be attributed to the writers, not the sponsors". France had the CCF-funded Preuves, under the leadership of Raymond Aron. If the editorial view took an anti-communist squint, it was hardly surprising in post-war Europe, with Stalin's corpse barely cold. We bought six issues at Quinto, ranging from 1953–61.

The inclination to impute wicked motives to Encounter has always struck us as an inverted form of radical chic. It was a beautifully produced magazine, especially in its earliest incarnation. It employed the world's best writers. Was Albert Camus a CIA stooge, for giving British readers in the first issue (October, 1953) a glimpse into Roman ruins in northern Algeria? His essay was published in English here for the first time, as were his notebooks, posthumously, in 1961:

"At the cinema the little woman from Oran weeps at the hero's misfortunes. Her husband begs her to stop. Look, she says, in the middle of the tears, let me make the most of it."

Encounter was not even right-wing. In 1954, Leslie Fiedler wrote a lengthy denunciation of Joseph McCarthy. Christopher Isherwood spoke admiringly of the "German writer and revolutionary", Ernst Toller. Richard Wright welcomed the emerging African independent nations. Dwight Macdonald, once a leading light at Partisan Review, became an associate in the mid-1950s. If it was part of a CIA plot to set the world to rights, it sounds like a good one. The interest of these old issues – £1.50 each, in fine condition – is exceptional. The brainwashing has so far been rather pleasant.

J. C.

November 11, 2011

Horror in many forms

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

The new issue of Granta is out (117), and the theme is horror. Despite the Halloween launch date, and the gothic typeface on the cover, there isn't all that much in the way of supernatural manifestations, otherworldly terror, gore, etc. With some exceptions – Daniel Alarcón on the Foam Weapon League, an LA-based crypto-Gothic fight club, being one of the more exuberant – the horror is altogether closer to home.

Julie Otsuka's short story focuses on the interactions of a woman losing her memory; and Joy Williams's was inspired by reports of a tragedy involving (as Granta sums it up) "a mildly disgruntled man, his placid wife and their peculiar son". Tom Bamforth writes about his experiences in Darfur as part of a UN envoy; and Santiago Roncagliolo about a childhood shaped by the Peruvian terrorist organization Shining Path. Will Self has contributed an essay (reproduced in part in the Guardian) about his diagnosis of polycythaemia vera, a disease (caused by a mutated gene) which results in an over-production of red blood cells. The treatment is regular bloodletting via a needle.

At a Granta launch event last week Self described the horror of that treatment – all the more distressing for a former intravenous drug user (it is a horror a touch exaggerated, he admitted, by an element of "Jewish kvetching"). Appearing with Self was the American poet Mark Doty. His piece on his experience of sexual insatiability takes as its starting point a fan letter from Bram Stoker to Walt Whitman – on whom, according to Justin Kaplan's biography of Whitman (2003), Stoker based the character of Dracula.

Doty's essay prompted discussion about the nature of addiction – in his own case was it, he wondered, a symptom of a perennial sense of lack within the self? A constant need to know himself in relation to other people? A form of love? – and about Stoker's literary intentions. The novel may well be a metaphor for repressed homosexuality, Doty said. ("Is there a novel of the late nineteenth century that isn't?", Self replied.) Self called Stoker "the Michael Crichton of his day": the character John Seward uses a phonograph, Mina Harker does a lot of typing and, according to Self, Dracula has a phone number. Our researches here suggest that he was joking – but we'd be happy to be proved wrong . . . .

Granta 117 will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

November 10, 2011

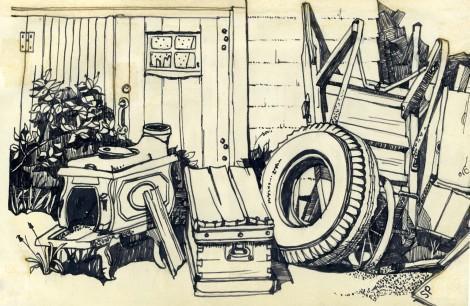

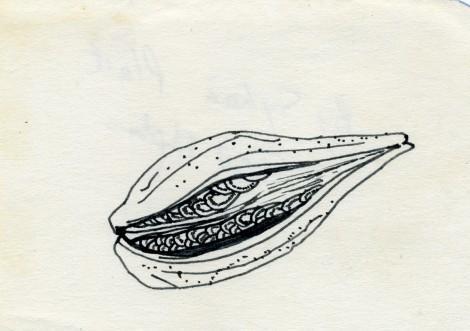

Sylvia Plath, the doodler

Gaps in Sylvia Plath's story will, of course, always remain. Emphases, like manuscripts, can be misplaced. Shadows grow and details fade, so that the fact of suicide and the acknowledged themes in her work – rage, pain, depression, redemption, "the horror of man's being a creature that dies" (Derwent May reviewing Ariel, TLS November 25, 1965) – displace the everyday experiences of a young student from Smith College travelling to Paris with her boyfriend in the early 50s; of a newlywed honeymooning with Ted Hughes in Benidorm in 1956; of a mother's "wondering pleasure in her children, or of gratitude when 'the world / Suddenly turns, turns colour'" (another aspect of Ariel described by May in the same review).

At an exhibition of her drawings at the Mayor Gallery in London we see Plath the sketcher, the doodler, the draughtsman. This is the woman described by Hughes as never more radiant than when she had spent a day indoors drawing a still life.

Many of the works, pen and ink on paper, will resonate with readers: an abandoned pair of high-heeled shoes called "The Bell Jar" evoke the part in her novel when Esther Greenwood, contemplating death by drowning, kicks off her shoes on the beach and leaves them facing out to sea, "to be like a sort of soul-compass after I was dead".

There are happier, postcard-like images, too, of small Spanish fishing villages, the rooftops of the Left Bank in Paris, rusty teapots and "The Pleasure of Odds and Ends":

In 1968, the literary critic David Holbrook complained that his "serious critical work" on Plath was being stifled by Plath's executor Olwyn Hughes (her sister-in-law) who, he said, refused even to look at his proofs of Dylan Thomas and Sylvia Plath and the Symbolism of Schizoid Suicide. Ms Hughes replied that she had made no such statement but that she was concerned about the form that Holbrook's criticism took: "He writes for instance 'one has to examine Sylvia Plath's work while remembering that some of it will be insane", and describes The Bell Jar as "a horrifying autobiographical account . . . of an American girl who goes mad."

Holbrook's book disappeared – or at least his original version did. His Sylvia Plath: Poetry as Existence (1976) was described by Anne Stevenson in the TLS as "clumsy" and "a little heavy-handed" and she warned: "we must not forget, though, that schizoid as she may have been, Sylvia Plath was above all a poet." (Stevenson went on to write her own version of Plath in Bitter Fame: A life of Sylvia Plath, 1989.)

But Plath's drawings were more than just diversions or decorative additions to her words – sometimes they were intended to take centre stage. Having sketched a composition of three sardine boats in Benidorm, she wrote "I'm going to write an article for them to send to the Monitor". If only these pictures had been on show in 1968 during the Holbrook–Hughes affair. How tempting to respond to Holbrook's psychological profiling by pointing out, "No, Sir, look – this is what a study of a nut looks like":

All images are by Sylvia Plath, copyright Frieda Hughes, courtesy of the Mayor Gallery.

November 9, 2011

Poppy wars

Rarely does Fleet Street speak with one voice, but on the vital matter of the poppy and the England shirt, there seems to be consensus. In case you missed it, or assumed that what England and Wales footballers wore on their shirts was a matter of overwhelming triviality, I'll fill you in. At a couple of international friendly matches to be played over this weekend, the governing bodies of English and Welsh football have requested that the world governing body, FIFA, allow the players to appear with poppies embroidered into their shirts. FIFA have refused the request, on the grounds that their rules specifically stipulate that players' shirts should not carry political or religious messages, and that to make an exception would "jeopardise the neutrality of football".

Cue outrage.

"Rat Blatt snubs poppies", said the Sun (Sepp Blatter is the head of FIFA). "FIFA's Poppy ban shows lack of respect" was the Mirror's more sober take. The Guardian chose to point out that the "Fifa ban on England's poppy kit was condemned by war veterans", while the Telegraph reported that the Prime Minister, David Cameron, had called the ban "ridiculous". As the UK sports minister explained, "it is not religious or political in any way. Wearing a poppy is a display of national pride."

Leaving aside the debatable idea that displaying national pride is a non-political act, I wonder how so many have convinced themselves that the poppy should be an exception. Its origins lie in the work of one of the most controversial figures of the First World War, Earl Haig, whose work for the Royal British Legion raised money for veterans and commemoration. This work has often (though probably wrongly) been seen as Haig's way of restoring his good name among those who thought his strategic approach put no value on servicemen's sacrifice. Supporting veterans and remembering the fallen were and are admirable national causes, but they are hardly non-political ones. You don't have to be Clausewitz to think that fighting wars, and the consequences of fighting wars, are political acts. They don't become non-political just because they are in the past. You only have to go to Northern Ireland to see that wearing a poppy is a deeply political act, one which will be met with approval in the Shankill Road and which is inadvisable, to put it mildly, in the Falls Road.

This is, understandably, an emotive issue, but that's why governing bodies and rules exist, so that emotions do not guide decisions. I should probably say that I wear a poppy myself and would encourage others to do so, but FIFA is absolutely right not to relax its rules. Too often the British assume they are exceptional. Our Empire was better than everybody else's, we go to war for noble reasons, we play fair. The howls of outrage that greet any challenge to such notions are noises to distract attention, not arguments that we should take seriously. The poppy is a deeply ingrained political (and quasi-religious) symbol, which marks the sacrifice of men and women in the cause of one of the purest political expressions of national interest: the preservation of the nation through waging war.

November 7, 2011

Steve Jobs: the precise diagnosis

Back in the office, after a brief time away, I find the massive biography of Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson.

I am tempted to review it for the TLS myself.

But only briefly tempted.

What I know about the inner workings of the iPhone could be written on a silicon wafer - or on one of those tiny shards of 'rare earth' that children hunt in Congolese mines. I have an iPad but use it much less than once I had hoped.

I know only one relevant thing - a bit about the type of cancer that killed him. Ten years ago the same one almost did the same to me.

A pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour was the problem in both our cases. I know that this pancreatic NET, the one that was once my cancer and his, is significantly different from what a cheerful consultant once described to me as 'bog-standard pancreatic cancer'.

It may seem an unimportant difference until you are playing host to one of them. But for the sufferer it is a vital distinction that most articles about Steve Jobs's death have failed to make at all.

The NET is indeed a nasty beast but it is rare, sluggish and, with much skill (other people's) and even more luck (the patient's) it can be defeated.

The 'bog-standard' kind of pancreatic cancer (the unpleasant adjectival construction was once briefly fashionable: something to do with Tony Blair and comprehensive schools) is not so kind.

After my NET and I had parted company in the year 2000, I joined the NET Patient Foundation a charity that aims to raise awareness of the condition. The more that doctors and patients recognise it, the more lives will be saved. That is our purpose.

Some small compensation for the loss of Jobs might have been some help, in making more patients and doctors recognise NET symptoms in one organ before their harm has moved, sluggishly and often fatally, to another.

But, as the NET Patient Foundation has quickly discovered, the millions of words about the Apple pioneer have not helped at all. In the media the distinction has been almost everywhere missed. There has been no 'Steve Jobs effect' in raising knowledge of the disease that killed him.

Most of the emphasis has instead been on his belief that he could cure his cancer by carrots and acupuncture, a course of inaction that might have been reasonable (though controversial) towards a catastrophic 'bog-standard' pancreatic tumour but was irrational (to put it mildly) in his case.

Jobs's NET was detected early - which should, as Isaacson says, have helped him. He was 'lucky', luckier than most. Pages 452-454 are chilling in their discussion of how the stubborn will of the genius engineer becomes the obstinacy that was fatal to him.

But that is helpful only in understanding the character of Steve Jobs. A rather wider gain in understanding has been missed.

November 5, 2011

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 5

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part V. This tour of duty takes the title "Back to Basics". Readers insisted we ditch newfangled conceptualism and get back to plodding round the capital's bookshops. The hebdomadal idea is to find a neglected work by a well-known author, for about £5. Thus is the annual plague vanquished. Our fellow citizens need no longer live in fear of Do Ants Have Arseholes? and other Christmas viruses.

Last week, we boarded the Central Line and headed east. Disembark at Bethnal Green, turn into Roman Road, pass an unlyrical block of flats named Swinburne House, continue beyond the malignantly prosaic Keats House: you are now opposite the wittily titled LXV Books, at No 65, a compact shop on two floors. The stock is all-purpose. There is a mild gay tilt. Preparations were in train for an evening event, which the friendly owner, Sebastian Sandys, expected to be packed. A young woman asked for William Burroughs's Junkie, which she had "started reading in a friend's house", and wished to continue. "I tried Naked Lunch, but it was too much." Sebastian could promise Junkie by morning.

Our objectives were more temperate. No one speaks about Pamela Hansford Johnson any more, though in 1956 a TLS reviewer could say that she possessed skill "well out of the range of most novelists". She was brought up in Clapham by her mother, who earned a living as a typist, and was expected to take the same route after leaving school at sixteen. This kind of background in writers appeals to us. Instead, she met Dylan Thomas and almost married him. Her early novels – she wrote about thirty – had titles such as This Bed Thy Centre and Girdle of Venus, hard to say now without a giggle. The Last Resort, published in 1956, is about a woman who emerges from an illicit affair into a "last-resort" marriage with a homosexual. Near the end of the book, Celia announces her intention to two friends, Aveling and Nancy:

"But there are other men", Aveling said desperately, "there's no need to do this."

"Are there other men? I don't find them like flies around a honey-pot."

Nancy darted frightened glances from one of them to the other. She, too, believed that Celia was mad to think of such a thing.

The Last Resort is evocative of a type of mid-century, middle-class existence which appears distant now. Even the couple's plucky intention to "make a go of it" seems rooted in its time. For a solid 1960s Penguin, LXV charged us £2. The teenage typist ended up as Baroness Snow, the wife of C. P. Snow.

J. C.

November 2, 2011

Going, going, Goncourt

This year's Prix Goncourt has been awarded to the forty-eight-year-old Alexis Jenni for his resonantly titled first novel, L'Art français de la guerre (Gallimard). The most prestigious prize in French publishing is worth the princely sum of 10 euros but guarantees healthy sales; the novel, which was widely praised on publication this autumn, has already sold 50,000 copies but the Goncourt can deliver sales in excess of 400,000.

This is not the first time in recent memory that a first novel has won the prize: Jean Rouaud's Les Champs d'honneur (largely about the First World War) did so in 1990 as did, more recently, Jonathan Littell's door-stopper Les Bienveillantes (2006), the fictional autobiography of an SS officer.

Jenni's triumph further confounds the vaguely held belief that French readers, critics and judges of literary prizes aren't interested in historical novels. His book, over 600 dense pages long and epic in scale, spans the years 1943 to 1991, taking in the war in Algeria as well as France's misadventures in Indochina. The 1991 cut-off date marks the first Gulf war.

Jenni, who teaches biology at a lycée in Lyon, describes himself as coming from a left-wing and anti-military family. He also charmingly suggests that he has up until now been a mere "écrivain du dimanche". L'Art français de la guerre will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers