Peter Stothard's Blog, page 82

September 29, 2011

Tagore in Segovia

This just in from our woman in Segovia: the film director Sangeeta Datta holding a copy of the TLS.

It turns out that the Hay Festival Segovia last week paid tribute to the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, following the 150th anniversary of his birth. This makes more sense of the photo of Ms Datta, who stood in for the actress Sharmila Tagore by reading and singing some of the Nobel Laureate's poems as part of the celebrations. These also included a bout of Bharata Natyam (a classical form of Indian dance; see below), and several related talks and events.

Seamus Perry, in his own recent tribute to Tagore in the TLS, began by noting that his work is still known and loved in India but is barely read at all in other parts of the world. Is this true? Segovia aside, that is, where the novelist Upamanyu Chatterjee was on hand at least to confirm Tagore's status in India as a national institution, a colossus, a giant. Imagine English literature without Shakespeare, Chatterjee suggested: that's Indian culture without Tagore.

*

It's not just reference books that cause controversy in Spain. As Catalonia prepared to stage its last bullfight, an adoring Segovia audience listened to a man who has killed more than 4,000 bulls in his career as a torero. For Enrique Ponce, bullfighting is a vocation and an art. The intensive training inspires a transcendence of mind. In the ring, he finds pleasure and inner peace. He condemned the Catalonian ban on bullfighting as the work of opportunistic "separatistas", concerned only to mark themselves out from the rest of Spain.For the "aficionados" who followed him, in a one-sided panel discussion, it isn't just a matter of art, beauty and passion – which is also the view of Alexander Fiske-Harrison, whose book Mark Rowlands savaged in the TLS recently, and who has duly responded in the letters page this week – there is also an environmental imperative to kill bulls. (Never mind that Ponce had earlier stated that the "toros bravos" were bred purely for bullfighting, to die in the ring.) Finally, clinching the argument, the writer and director Agustín Díaz Yanes declared that bullfighters were the only free men left in the world. What's the death of a few bulls compared to that?

*

Elsewhere, the discerning Segovian (not necessarily in this sense of the word) might have heard Lord Desai talking about the relationship between India and China, Eduardo Mendoza on his novel Riña de gatos, and David Mitchell on the historical novel, discovering the themes that matter to him (the main one being language) and how a writer striving to be original cannot prevent things popping up again from one novel to the next ("like the whack-a-mole game . . .") – and how he is currently reading Independent People by another Nobel Laureate, Halldór Laxness – due for his own sesquicentennial celebration at Segovia 2052, presumably.

September 27, 2011

Death of a philosopher

The news arrives from Oxford that the philosopher, Bede Rundle, is dead. We will miss him - at Trinity and far beyond.

The news arrives from Oxford that the philosopher, Bede Rundle, is dead. We will miss him - at Trinity and far beyond.

He combined brilliance, ambition and modesty in the best tradition of his craft.

In 2004 he wrote a wonderful short book called Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing.

And in its introduction he gave a rare written flavour of himself'

'A theory of everything is not our business, but a philosophy of just about everything philosophy dreams of is needed, and the analyses that follow patently fail to meet that need'.

He may not have met that need by his necessarily high standards but his aim was strong. As an opening tribute of what, I am sure, will be many tributes, there follows Thomas Nagel's review of Bede's book from the TLS of May 7, 2004.

********

"The question "Why is there something rather than nothing?" provoked one of Sidney Morgenbesser's memorable comebacks: "If there was nothing, you'd still be complaining!" Bede Rundle's response is somewhat longer but just as uncompromising. He argues that the question is ill-formed because there could not have been nothing. He offers general reflections on causality, eternity, God, mind, matter and agency, in order to evaluate the idea that the existence of anything at all, while it cannot be explained by science, might be explained by theology. His strategy in Why There is Something Rather Than Nothing is to argue in detail that the question, and the attempts to answer it, consistently take language beyond the bounds of meaningfulness, detaching familiar words from their usual conditions of application so that they no longer express intelligible possibilities. He is following the method of Wittgenstein, as he conceives it, though with results more destructive to religious language than Wittgenstein's own view.

The linguistic transgressions that Rundle finds fall into three categories: the idea of God, ideas of causality and explanation, and ideas about existence. They appear in the thought that, though science can explain what goes on in the universe by discovering the systematic connections among its features and elements, the existence of the universe as a whole clearly cannot be explained in this way, ensuring that we must seek an explanation of it in something that is not part of the universe, but outside of space and time. And if that explanation is not to leave us with a further demand to explain the existence of what we have identified as the ultimate cause, then that cause has to be something whose existence does not require explanation -something that couldn't not exist. This role has been traditionally attributed to God.

It is important that in talking about the existence of the universe, Rundle is not using the term "universe" in the peculiar way that is now common, to mean a particular cosmic entity that might be only one of many such entities, either coexisting or succeeding one another. In this recent sense of the term, it is possible to say that our universe -the one we live in -came into existence with the Big Bang, but that this was perhaps preceded by the contraction of a prior universe into the concentrated point from which the Big Bang exploded, or that it perhaps arose from a black hole in another universe.

In this sense, the existence of our universe might be explained by scientific cosmology, but such an explanation would still have to refer to features of some larger reality that contained or gave rise to it. A scientific explanation of the Big Bang would not be an explanation of why there was something rather than nothing, because it would have to refer to something from which that event arose.

This something, or anything else cited in a further scientific explanation of it, would then have to be included in the universe whose existence we are looking for an explanation of, when we ask why there is anything at all. This is a question that remains after all possible scientific questions have been answered.

Rundle effectively dismisses as incoherent the idea that it could be answered by the hypothesis that God created the universe at some time in the past. He says that this tries to employ the idea of an agent producing something, while withholding two of the crucial conditions of the concept of agency: time and physical causation. We can understand the idea of God moulding Adam out of clay, but the idea that a nonphysical God whose existence is neither in space nor in time might cause space and time to start to exist at a certain point simply takes the idea of cause and agency off the rails. A non-spatio-temporal being, if there could be such a thing, couldn't do anything.

Much of Rundle's discussion has this down-to-earth, common-sense flavour. Look at the ordinary way in which we use the terms "cause" or "mind" or "exist" or "nothing", and you'll see that in theological speculation they are being used in a way that tears them loose from these familiar conditions without supplying anything to take their place. The minds we can talk about are revealed in what people with bodies do in space and time. When a mental intention brings something about, it is through intentional physical action in an already existing world. The problem Rundle finds with most theological claims is not that they are unverifiable, but that they are unintelligible. He goes on to say, however, that even if we reject the thought that God might have brought the universe into existence in the past, there remains another version of the question that seems to require an answer. The universe may neither have, nor be susceptible of, a causal explanation, but the why- question seemingly remains. Not "Why does it exist?" where a cause of becoming is sought, but "Why does it exist?" where the query is motivated by considerations of modality: the universe need not have existed, surely, so the fact that it does is a fact that calls for explanation.

Even if God did not create the universe from nothing in the past, perhaps He sustains the universe in existence at all times, preventing the fall into nothingness.

It is this possibility of absolute nothingness that Rundle is mainly concerned to expose as an illusion. He points out that, in ordinary speech, when we say there is nothing in the cupboard, or nothing that is both round and square, we are talking about an existing world none of whose contents meet a certain description. To say nothing is X is to say everything is not X. We can perhaps conceive of the disappearance of everything in the world, so that there are no things left in it, but even then we are not imagining nothing at all, but rather a void, a vacuum, empty space. Taken literally, the hypothesis that there might have been nothing at all seems self-contradictory, since it seems equivalent to the supposition that it might have been the case that nothing was the case. Is there any way of understanding the possibility that there might have been nothing at all without interpreting it incoherently as a way things might have been -a fact, as Rundle puts it, a possible state of affairs, an alternative possible world? Rundle thinks not, and that therefore the question "Why isthere something rather than nothing?" does not call for an answer.

Even if it is inconceivable that nothing whatever should exist, it does not follow that there is any particular entity whose existence is necessary. Yet Rundle has a view about the kind of thing that has to exist: not God, but matter. He is not a materialist, for he doesn't think all other kinds of truths are equivalent to physical truths. But he does hold that our mental and mathematical concepts, for example, depend for their application on features of the physical world. "The thesis that nothing can exist in the absence of a material universe does not imply the nonsensical view that everything is material, but we can hold that if anything exists, matter exists, on the grounds that it is only in matter that the necessary independent existence is to be found." One consequence is that "if there is no place for immaterial agents, then there is no place for God".

Even if one does not accept many of Rundle's Wittgensteinian interpretations of the way ordinary language works — interpretations that depend heavily on conditions of assertability available to the speaker -he has offered a serious challenge to the intelligibility of what is widely regarded as a fundamental question, as well as to one type of answer. And he does not admit the saving position that Wittgenstein himself apparently favoured -that religious language does not make factual claims at all, but rather expresses an attitude towards the world. But it will not come as news to those who believe that God is responsible for the existence of the universe that they are not using words in the sense they bear in their ordinary worldly context. As Rundle acknowledges, claims about the attributes and acts of God are supposed to be based on a very distant analogy with what is meant by "mind", "good", "cause", or "create" in ordinary speech, and it is thought that we cannot grasp the divine nature but only gesture towards it with such analogical language. He rejects this kind of meaning as an illusion.

The most difficult philosophical question posed by Rundle's critique is whether such efforts to use words to indicate something that transcends the conditions of their ordinary application make sense. This question is especially acute with regard to the why-question itself, which is immediately gripping even to people who find a theological response ineligible for reasons like Rundle's. Though it is likely to make you giddy, it is hard to cast off the thought that there might have been nothing at all -not even space and time -that nothing might have been the case, ever. It is not a thought of how things might have been. It is not the thought of an empty universe. Nevertheless, it seems an alternative to all the possible positive ways the world could have been -an alternative both to the actual universe and to all the other possible universes that might have existed instead, each of them crammed with facts.

Perhaps each of us can imagine it on the analogy of our own non-existence. The possibility that you should never have been born is an alternative to all the alternative possible courses of your experiential life, as well as to your actual life. From the objective point of view, of course, this is a perfectly imaginable state of affairs, but it is not an alternative possible course of experience for you: subjectively it would be not something different, but nothing. The possibility that there should never have been anything at all is the objective analogue to the subjective possibility that you should never have existed. While it is risky to use existing language to reach beyond its existing limits, we are impelled to do this again and again, however inadequately, in our recognition that our understanding of reality is so limited.

This applies also to the question "Why?" which we seem capable of raising about anything, even if we have no idea what would count as an answer. Bede Rundle's brief and often forceful book is a wonderful stimulus to reflect on the ways in which philosophy can and cannot identify the excesses of attempted thought."

September 26, 2011

Hope Mirrlees and the Forgotten Female Modernists

Like Mina Loy (whose Stories and Essays I have just reviewed in the TLS), Helen Hope Mirrlees (1887–1978) is a fine example of the "forgotten-female-Modernist" (FFM for short). She spent much of her life in transit, writing poetry but also, in the 1920s, three novels. But, unlike Loy, she was not in flight from an oppressive domestic situation or a destructive love affair. When she wrote her best-known work, the long, psychogeographic poem Paris, shortly after the First World War, she was living in the 6ème arrondissement with the classics scholar Jane Harrison (the original don of Newnham College). (Virginia Woolf described them in a letter to Mary MacCarthy as living in a "Sapphic flat somewhere".)

They had met when Harrison tutored Mirrlees at Newnham a decade earlier, after which they became companions, with Mirrlees nursing Harrison – almost forty years her senior – up to her death in 1928. Indeed, it is mostly through her association with Harrison that Mirrlees has featured in academic discourse so far. With the exception of Michael Swanwick's biography of Mirrlees, Hope-in-the-Mist (2009), and the late Julia Briggs's work – notably her essay in Gender in Modernism: New geographies, complex intersections, edited by Bonnie Kime Scott (2007) – Mirrlees has been edited out of the history of Modernism.

Now after Sara Crangle's edition of Mina Loy, it is with great pleasure that I find, on my desk this morning, the Collected Poems of Hope Mirrlees. Two FFMs in quick succession – the likes of Loy and Mirrlees are now being remembered it seems. What Sandeep Parmar's enlightening introduction does well to emphasize, however, is how much of the forgetting was done by Mirrlees herself. She is, in this sense, the FFM par excellence. Paris was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf's Hogarth Press in 1920 (only the fifth book in their catalogue), and right up to and beyond the printed version, Mirrlees scrawled corrections and comments in the margins, insisting on particular typographical choices, and much to Virginia Woolf's frustration, changing the order and inserting a number of misspellings (accidentally, we presume). Mirrlees was tireless in her self-editing, it turns out. Fifty-two years on, following her conversion to Catholicism, she revisited Paris to cut out what she regarded as the many "blasphemous" passages. Parmar describes the original poem as unfinished, or unfinishing, compared to the "highly formal, mannered verse" she wrote in the 1960s.

The fact that Mirrlees and Loy have been re-issued after so many years out of print, shows that they might yet play an important role in Modernist studies. It seems from a review of Paris published in 1920, quoted by Parmar, that the TLS missed out on Hope Mirrlees the first time round:

"This little effusion looks at the first blush like an experiment in Dadaism; but there is a method in the madness which peppers the pages with spluttering and incoherent statement displayed with various tricks of type . . . . It is certainly not a 'Poem', though we follow the author's guidance in classing it as such. To print the words 'there is no lily of the valley' in a vertical column of single letters might be part of a nursery game. It does not belong to the art of poetry."

Thank goodness for second chances.

September 25, 2011

Three days in Rome

This afternoon, not in Rome but at least by the waters of the Thames, I have read the whole of next week's TLS.

The only bad thing about becoming editor of this great paper - almost a decade ago now - is that I lost the thrill of sitting down with an old TLS on a Sunday afternoon and reading almost everything in it.

Reading the next one - and most of it not for the first time - is not quite the same.

But it was a lovely sunny afternoon. And old or new, there can be always be strange interconnections within any issue read at a single sitting, not all of them intended.

Next week, I can reveal, is therapy week. Alfred Kazin's Journals follows Alice Munro's New Selected Stories.

Kazin, as Zachary Leader explains in a review well worthy of its subject (high praise and meant to be so) produced a 7,000 page journal of his life even though his thrice-weekly visits to his therapist removed the need for too much writing of irrationality and confession.

Munro's disturbing stories of sexuality and dreams, in an evocative lead review by Ruth Scurr, are cooled by the voice of therapy but powered by its irrationalities. I learnt that in the story, "Chance" (2004), there is even the presence of the classicist's own modern classic on the subject, E.R. Dodds' "The Greeks and the Irrational'.

Dodds' book is one worth rereading from time to time - as well as reading about. It does not stay the same. If I had had him to hand, I would have likely left more of the TLS for tomorrow in the office. But he was not with me by the river this afternoon. Nor were any other books. All are in boxes in a store nearby. The house from which many past posts have been made to this blog contains builders only right now.

So there was only next week's TLS - from cover to cover - in the Autumn sun among the geese. Most excellent it was - as I hope that many more readers, encouraged by this revived blog on our even more revived website, will soon discover. Subscribe now. You know it makes sense.

Driving back to London an hour ago, I happened to put on an old Sheryl Crowe CD, the one with the song, Three Days in Rome, about the woman who finds unhappily that her former lover has put their mini-break in a book.

A great song, as I just about recall from however long ago it was that it came out. It is one of those songs that once seemed by its anger and intensity to come from true experience. [That is the kind of loose feeling or statement that classicists avoid making about ancient poetry but is perhaps OK for pop songs]

This afternoon it seemed more like an echo of Portnoy's Complaint, a pop-song version of a Roman story delivered direct to his therapist by its hero. But that thought probably comes only from too continuous reading of the TLS.

September 23, 2011

Improving Hannah Cowley

2011, in London at least, has turned out to be a good year for – of all things – eighteenth-century drama.

Mind you, it only takes three productions to make it a good year for eighteenth-century drama: The Beggar's Opera at the Open Air Theatre in Regent's Park, The Rivals at the Barbican and now, in a more courageous move, The Belle's Stratagem by Hannah Cowley at the Southwark Playhouse (smartly tucked away under a railway near London Bridge).

Cowley's comedy of 1780 is a lively variation on Goldsmith's She Stoops To Conquer, in which the English heroine, Letitia Hardy, is promised in marriage to a young man called Doricourt, who comes back from the Continent in love with Continental sophistication and convinced that no Englishwoman could possibly match it. Letitia's "stratagem" is intended to prove him wrong, hilarity ensues, etc.

The Southwark production has been well received. The theatre critics have praised its considerable charms, and called it well conceived, or even unmissable. And if the "perfunctory" sub-plot is disappointing, there is some consolation in a fine supporting turn by Christopher Logan, the Kenneth Williams de nos jours. There are equally fine turns from Gina Beck (as Letitia), Robin Soans (as the belle's father), Maggie Steed and Jackie Clune (these last two forming a mischievous and witty double act), among others – as well as some exuberant musical moments, good, clear direction by Jessica Swale and high production values.

It's a pity that a couple of critics have repeated the misinformation (from a rogue press release?) that the original production of the play was closed down by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. From memory, I'd say that's unlikely, as Sheridan was playwright-manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane at the time, and The Belle's Stratagem was first staged at Covent Garden. So this may be one of those convincing myths (with a famous name attached, and hints of jealousy and sexism) that unfortunately gets repeated into truth . . . .

But the other thing the critics seem to have missed was actually on stage. The fourth act of The Belle's Stratagem is dominated by a masquerade, through which weave most of the play's characters in disguise, as the occasion demands. Cowley has Letitia's father rather ineffectually attempting to meddle in her cunning plans for teaching Doricourt a lesson, by disguising himself as "cunning little Isaac" – ie, as Isaac Mendoza, a character in Sheridan's highly popular comic opera The Duenna. The meta-theatrical in-joke for Cowley's audience was that Letitia's father was played by John Quick, the short comic actor who also played Mendoza. When it came to the Belle's Stratagem masquerade, Quick would therefore be borrowing a (perfectly fitting) costume from himself.

In the current revival, however, Letitia's father Mr Hardy decides to go to the masquerade as a fine lady. There aren't really any "hilarious consequences" to this, as Mr Hardy's role in the scene is fairly small, but cutting "little Isaac" from the masquerade also means cutting lines directed at him by his fellow masqueraders, such as "Why, thou testy little Israelite!" and "Look at this dumpling Jew!".

Presumably, it was thought, a modern audience would be more comfortable with the cross-dressing. And it's thematically justified by the play's forthright commentary on male assumptions about how women should behave. But it means that in one significant respect, this isn't The Belle's Stratagem familiar to late eighteenth-century audiences.

I don't mean to suggest that theatre-makers now should respect play-texts by not altering them at all – on the contrary, The Belle's Stratagem at Southwark shows how a revival can also be a sensitive adaptation of the original. But why so silent about it? (There is no note about it in the programme.) Would it spoil the production's claim to be a landmark rediscovery?

September 21, 2011

Diccionario or Ficcionario?

Spain's cultural wars go back at least to Napoleonic times, when liberalism became a dirty word to those who associated it with the French invaders. The ramifications proliferate: in recent years, Left–Right argument has centred on matters such as provincial autonomy, multiculturalism and gay marriage. Now, though, a book-based controversy has prompted a fresh exchange of fire over the most contentious subject of all in Spain – namely, the Civil War and its aftermath.

As is sometimes pointed out, history has largely been written by the losing side in this case. Anglophone observers, accustomed to seeing the conflict as a dress rehearsal for the battle against Hitler, find it hard to view the defeated Republic in anything other than rosy terms. This background – and the allied urge of conservative Spanish scholars to right the balance, as they see it – appears to have informed work on the fifty-volume Diccionario biográfico español, the first instalments of which appeared earlier this summer. Produced under the auspices of Spain's Real Academia de la Historia, this colossal project was modelled on works such as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in Britain. Handled well, the Diccionario might have given a balanced hearing to historians from across the political spectrum. On the basis of the twenty-five volumes published so far, though, there are signs that the work as a whole leans to the Right – a bias encapsulated by the choice of Luis Suárez Fernández, a medievalist known for his Francoist sympathies, to produce the entry on the generalissimo himself. Suárez Fernández's article is stodgily written and mainly sticks to the facts. But it has drawn heavy criticism for failing to describe Franco's regime as a dictatorship.

Should we see this and other examples as indications of bad planning by Gonzalo Anes, Director of the Real Academia de la Historia and the Diccionario's commissioning editor, or are there more disquieting influences at work? Paul Preston, Franco's biographer, believes there is clear evidence of systematic bias: "Passing references to [leading Republicans] are ferociously hostile . . . I know of no liberal or left-wing historians being invited to take part – no Enrique Moradiellos, No Ãngel Viñas, no Santos Juliá, no Julián Casanova".

Another prominent British Hispanist blames the debacle on carelessness above all. "The Academia de la Historia is a joke full of stuffed shirts. Gonzalo Anes was once a serious historian, but has become a social butterfly in recent years. One of my graduate students could have done a better job on Franco than Suárez Fernández."

Meanwhile, the Spanish press has seen further heated exchanges about what critics have christened the "Ficcionario". As further volumes become available, the TLS will be noticing the work in due course.

September 20, 2011

Intellectual peat

"During the Parliamentary Session LITERARY SUPPLEMENTS to 'THE TIMES' will appear as often as may be necessary in order to keep abreast with the more important publications of the day."

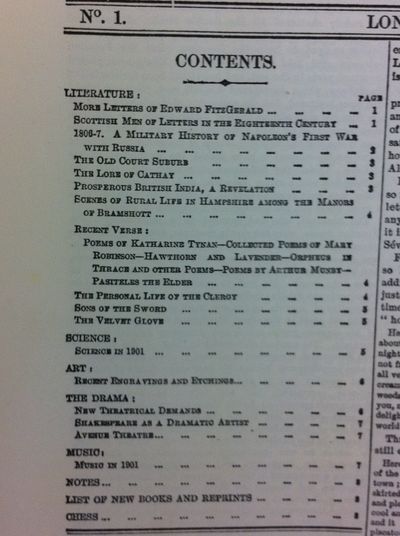

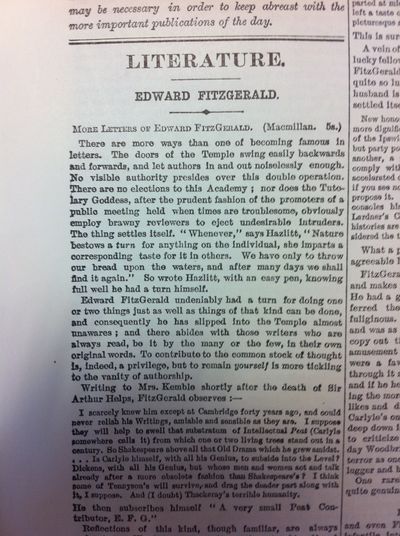

That's how the TLS announced itself on January 17, 1902, when the first issue appeared. (Starting out on a new TLS blog has sent me back to look at the useful office copies of the paper itself, as in the photographs below.)

Apparently, in 1902, "to keep abreast" of the important books meant keeping abreast of books about Scottish men of letters in the eighteenth century ("eminently readable"), the "case against British government in India" ("inconclusive") and science ("Professor Gamgee's investigations into the magnetic qualities of the blood . . . touch physics on the one hand and physiology on the other"). It meant F. Loraine Petre's account of Napoleon's first war with Russia (". . . fills an important gap in English Napoleonic literature"), as well as two attempts to write "a good Napoleon novel" ("it is a story in which all will find something to their taste"; "a fascinating little heroine . . ."). It meant opening a survey of half-a-dozen new volumes of poetry with the (rueful?) observation that "There is no slackening in the current of contemporary verse . . .".

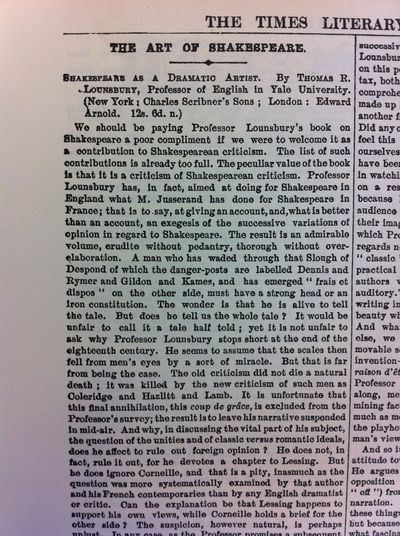

Some cast their contemporary opinions as the views of posterity. The reviewer of Shakespeare as a Dramatic Artist by Professor Thomas R. Lounsbury, for example, predicted a future in which the scholars of 1902 might seem as quaint as their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors did to them: "What Rymer seems to Professor Lounsbury the Professor may seem to some other Shakespearean commentator two centuries hence".

But perhaps the most striking insight into the distance between them and us, then and now, 1902 and 2011, comes in the very first review in the issue, on More Letters of Edward FitzGerald.

Here a letter is quoted in order to show FitzGerald's awareness of what Posterity would soon do to his writing friends and other contemporaries – how it would reduce them, bar one or two, to a "substratum of Intellectual Peat":

"Is Carlyle himself, with all his Genius, to subside into the Level? Dickens, with all his Genius, but whose men and women act and talk already after a more obsolete fashion than Shakespeare's? I think some of Tennyson's will survive, and drag the deader part along with it . . . . And (I doubt) Thackeray's terrible humanity."

FitzGerald signs off as "A very small Peat Contributor, E. F. G.". But he didn't seem quite so small to the reviewer of these posthumously published letters. Although the review begins with a vision of a kind of literary Temple of Fame, with doors that "swing easily backwards and forwards, and let authors in and out noiselessly enough" (an appropriately library-like conceit?), the conclusion turns to FitzGerald's masterpiece, The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. What would have happened if, say, every copy of this ingenious "paraphrase of Omar" were to be "destroyed by fire to-morrow"?

Why, "we very much doubt whether there is a town in England of over 40,000 inhabitants which could not produce a sufficient number of citizens whose united memories would prove equal to the task of dictating the entire version to a type-writer".

If only a town with the requisite population had gathered around the typewriter to put this fine piece of praise to the test. . . .

September 19, 2011

Welcome to the new TLS blog

Welcome to the new TLS blog – over the past six years, the paper's editor Peter Stothard and the classics editor Mary Beard have blogged about everything from Belgian museums and David Starkey to lost cameras and bad versions of Roman history. While Mary continues to blog separately, from now on Peter will be joined by other members of the editorial staff, including Lucy Dallas, David Horspool, Robert Irwin, Thea Lenarduzzi, Rozalind Dineen, Catharine Morris, Rupert Shortt, and me. We'll be talking about books and ideas, literary events, and – well, anything else that takes our fancy.

So you might call this a supplement to the Supplement . . . .

We'll be eavesdropping, as it were, on the paper itself, listening out for anything striking, troubling, amusing, intriguing, inspiring, enchanting, enlightening, argufying, or otherwise noteworthy and thought-provoking.

Right now, that might be something about the birds and the bees, the new novel from the author of Stasiland, Anna Funder, or Rabindranath Tagore. It might also mean, from the website-only side of things, the latest Poem of the Week or one of those debates about Shakespeare that ran and ran.

But we hope that it is also in the spirit of the TLS itself – the paper that once described T. S. Eliot's poems as "the ravings of a drunken helot". (He was a contributor.)

August 10, 2011

Coming soon at the TLS: New bloggers for old

The slow rebuilding of the TLS website has tested the patience of readers and writers alike.

The slow rebuilding of the TLS website has tested the patience of readers and writers alike.

A few weeks ago my plan was to continue my six-year path of solo blogging on our site until the new TLS online was ready.

And then, and only then, I hoped to lead my colleagues into a new TLS Blog in which all of us, or some of us anyway, would post more regularly about this and that, on a wider range of subjects, in a wider range of languages, to the general greater good.

But instead, and without conscious decision, I stopped the old before the new had begun.

A blog turns out to be deeply attached to the blogger's brain. Somehow the decision to replace it in the future had turned the switch for immediate cessation.

Thus the new TLS blogging team met this morning to accelerate its replacement.

We had an enthusiastic discussion.

By the end of August, this Peter Stothard blog will officially cease.

And, from that time on, I will be back posting here alongside the wisest band of electronic critics we can summon from our midst, a very wise band indeed.

They will all introduce themselves at the due time — which will be soon.

Thankyou for staying around.

Watch this space.

Mary Beard's inimitable career as a solo blogging artist will continue triumphant and unaffected.

June 29, 2011

Mary Beard on Robert Hughes on Rome

Mary Beard, writing on The Guardian website today, has read more of Robert Hughes's Rome than I have so far - and found her own list of 'errors and misunderstandings' that will 'mislead the innocent and infuriate the specialist'. See my previous post.

Mary Beard, writing on The Guardian website today, has read more of Robert Hughes's Rome than I have so far - and found her own list of 'errors and misunderstandings' that will 'mislead the innocent and infuriate the specialist'. See my previous post.

The innocent, I think, are the ones that deserve the greater consideration here. Readers of newspaper reviews stand in some danger of being deceived. See, eg, this effusion, also from The Guardian.

Hughes is a famous writer of an expensive book from a respectable publisher.

As Professor Beard generously points out in her Guardian review, the only thing to do, if one gets this Rome as a gift, as many will, is to skip the first 200 pages.

If it were about the twentieth century 'it would have been pulped'.

There is still time.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers