Peter Stothard's Blog, page 83

June 19, 2011

Robert Hughes on Rome

I don't want to be picky but I have not had a good afternoon.

I don't want to be picky but I have not had a good afternoon.

A new history of Rome by the Australian historian and critic, Robert Hughes, has arrived.

Doubtless it will be widely reviewed. This morning The Sunday Times, here in London, hailed it as 'superb'.

The author 'couldn't have chosen a better subject for himself'', I read.

So two hours ago I settled down to enjoy the 'feast'.

I have bad reading habits sometimes. I browsed before I began.

And on the last page of Chapter Two, I read about the death of the Emperor Augustus and how 'smoothly' went the transition of power to his successor, 'Livia's eldest son by him, Tiberius'.

Peculiar?

If Tiberius had been Livia's son by Augustus, the succession might well have gone smoothly (or not) but Tiberius was Livia's son by her first husband Tiberius Claudius Nero, an interesting character who lost his wife to the most powerful man of his age but ended up siring a vast dynasty of imperial potentates.

An easy mistake? Well, quite easy, I suppose, unless you are writing a history of Rome (and have forgotten Robert Graves and all the soap-opera versions too). Augustus sired only one child, a daughter, a matter often considered of some historical and dramatic note.

Two pages further on there is another death, that of the African king, Jugurtha, 'of starvation in 105 CE'. Which would be a fine addition to a section on the Emperor Caligula's prison policy if Jugurtha had not died more than 200 years before.

OK. That's the old BC/AD confusion. Easily done. So easily that it's done in the next line too. Vercingetorix , 'Caesar's chief enemy in Gaul' , is executed in '46 CE', ninety years after Caesar himself was killed.

I have some personal interest in gladiatorial games. But I can still be surprised by a declaration that 'a succession of autocrats, starting with Augustus himself and continuing onwards through Pompey and Julius Caesar, treated them as the greatest imperial show of all'.

Onwards? This is the 'Times Arrow' school of history where forward is forever back.

And then two pages later we have reached the gladiator emperor, Commodus, not an obscure modern figure (above) following his role in the film, Gladiator, starring that Australian icon, Russell Crowe . In 138 CE Commodus was the 'son and successor' of the Emperor Hadrian, Hughes writes, which is odd when Commodus's father, as shown in the film and in all other history books, was the philosopher emperor, Marcus Aurelius whom Commodus succeeded some forty years after the date given here.

So after 24 pages I have now stopped reading this book.

The wise advice to myself might be to skip all the chapters before the Renaissance and to see what Hughes has to say about the Trevi Fountain. The excellent Jonathan Keates, I discover, has done that already.

But I can still wonder why someone wants to write ancient history when he has such a strange lack of concern for what is known about it.

I can wait to be accused of pedantry. We are used to that at the TLS. But these are not errors about the obscure; they are mistakes about some of the best known episodes and characters in the ancient history of Rome.

Once upon a time - not so very long ago - an editor at Weidenfeld & Nicolson would have quietly corrected the errors of a best-selling star; or the text might have been shown to someone who had read some schoolbooks or watched some late night TV.

But that sort of nostalgia is useless. Perhaps next week I will start again at the beginning - and hope pages 102-126 were just a bad patch.

June 6, 2011

Josephine Hart in a few words

Josephine Hart, who died last Thursday, was a master of minimalist fiction and a ringmaster of poetry. She produced six intense and personal novels, including Damage (filmed in 1992 by Louis Malle with Jeremy Irons), and many hundreds of hours of equally spare, precise and passionate readings of poems. When Bono and Bob Geldof growled out W.B. Yeats, Harold Pinter intoned Philip Larkin, Sir Roger Moore played Kipling and the darkest parts of T.S. Eliot became clear in the voices of Edward Fox, Jeremy Irons and Dame Eileen Atkins, it could only be at one of Josephine Hart's Poetry Hours, performances in libraries and theatres before audiences of devoted students and fashionable society, each show under Hart's firm and knowing directions, all of them written in the famed black-bound book that always sat on her knee.

Josephine Hart, who died last Thursday, was a master of minimalist fiction and a ringmaster of poetry. She produced six intense and personal novels, including Damage (filmed in 1992 by Louis Malle with Jeremy Irons), and many hundreds of hours of equally spare, precise and passionate readings of poems. When Bono and Bob Geldof growled out W.B. Yeats, Harold Pinter intoned Philip Larkin, Sir Roger Moore played Kipling and the darkest parts of T.S. Eliot became clear in the voices of Edward Fox, Jeremy Irons and Dame Eileen Atkins, it could only be at one of Josephine Hart's Poetry Hours, performances in libraries and theatres before audiences of devoted students and fashionable society, each show under Hart's firm and knowing directions, all of them written in the famed black-bound book that always sat on her knee.

Hart was an unmistakable figure in London for thirty years. She was never seen in the city unless dressed in black and white, usually demure and by Chanel, always on performance days in the same pompom-heeled 'lucky shoes': colour was only for the country. She could persuade and charm as few others could — even in places where such powers counted for the most. Her deep, close second marriage to the advertising agency creator and Conservative political strategist, Maurice Saatchi, placed her at the centre of power in the Thatcher era and beyond. But her own power was devoted to an iconic style of prose, expressed both in commercially successful novels and fictions that she knew would never sell so well — and to ensuring that the best of poetry in English be heard by audiences as well as read.

Josephine Hart was born in 1942 in Ireland in Mullingar, County Westmeath, the daughter of parents whose business was the ownership of a garage but whose legacy to their bookish daughter included a catalogue of family catastrophes. Three siblings died, two of them within six months of each other when she was seventeen years old. Her last novel, The Truth About Love (2009), which sets the history of modern Ireland against a family struggling with dismemberment in all its forms, came as close as she ever did to addressing directly these tragedies. Damage, which was her first novel and a worldwide best-seller, told of a successful but purposeless politician who meets destruction through a woman who warns him of the deeper truths that he cannot see: 'Damaged people are dangerous. They know they can survive'.

Hart was a pupil at Mullingar Catholic schools where the learning and reading aloud of poetry was compulsory — and writing, too, was praised and encouraged as God's work. She lost her convent Catholicism but kept the nuns' belief in the transformative power of poetry — for good and ill. She considered an acting career herself but instead chose an early life that did not put emotion in the fore. If life could be damaging so could art. She became a businesswoman, rising to be a director of the Haymarket publishing company where her first husband, Paul Buckley, also worked. She had two sons — Adam, from that first marriage, and Edward from her second. She produced West End plays. When she began her first staged readings of poetry — at a Cork Street art gallery in 1987 — she applied a seriousness to the project, both of inspiration and organisation, that made things happen that had seemed impossible before.

Would great actors work for no pay before small audiences reading Milton and Gerard Manley Hopkins and writers who rarely figure in a life on stage? They would, it seemed, if Josephine Hart asked them to. In 2005 Sir Roger Moore gave a rendering of Kipling's ballad The Mary Gloster at The British Library: the Hollywood star had not quite been expecting to perform a piece that was quite so long; the audience, made up of sceptics and the star-struck, was barely more certain what would transpire. Under Hart's hardest gaze, Moore proved his seemingly effortless power over Kipling's story of the helpless shipping magnate disappointed in his son, using no accents, no grand gestures or regional burrs — and left the rows of his watchers in tears. When Kenneth Cranham took on the Kipling duties (he had met Hart through a shared passion for Elvis Presley) it was as an equally potent, but very different, character part. Harold Pinter was never offered Kipling; Hart knew who would do what and why. Pinter did Larkin; before he died he was working on W.B. Yeats for a new Poetry Hour performance that never took place.

A controlled encouragement of variety was the key to Hart's productions on stage. When Bob Geldof had his rock star's pick of early Yeats — "The silver apples of the moon, / The golden apples of the sun" – there was the sight and sound of crouching concentration. The Boomtown Rat and campaigner for Africa was allowed to luxuriate before his fans in the familiarity of "I have spread my dreams under your feet; / Tread softly because you tread on my dreams". When the classical actor Sinead Cusack took over, she gave the "The Circus Animals' Desertion" a more classic tone: "Now that my ladder's gone, / I must lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart".

In the Ireland of Hart's youth there had been 'Holy hours' when it was wiser not to be seen entering or leaving a bar and when the trapped drinkers would perform – each to their own individual standard of excellence under the landlord's guidance. To some this was the key to her style – as much as were the convent and the classroom. She understood well the perils of production. In her skeletal third novel, Oblivion (1995), there is a gruesome scene in which a director sets out his skills before a documentary-making journalist, showing how he fires up his stars into "giving life to the dead". Not every one of her performances was a masterpiece. Not every actor repaid Hart's faith in his or her power to make poetry understood. But so many did so – and surprised even themselves in what they did. She made the most insecure feel secure. Thanks to CDs sent free to all British schools, the proof of that will live on.

Josephine Hart died on Thursday afternoon of a cancer whose existence few of even her closest friends had known. She recognised herself as a connoisseur of death and had chosen her way to meet it. Four hours later, on the bare black bricked stage of the Donmar Warehouse in Covent Garden, it was the actor, Deborah Findlay, who carried on stage the familiar black binder with the names of Larkin, Milton and T.S. Eliot. And with her was Cranham, representing the older generation of her cast, and Ruth Wilson and Rupert Evans representing the younger, and with them all Max Irons, son of Jeremy Irons and Cusack, probably the most regular of all Hart's players over three decades. There was a short, shocked exhalation from the audience when the news of the death was announced. Then there were readings, as planned, of war poetry – by Yeats, Owen, Sassoon, Brooke and epitaphs by Kipling.

May 26, 2011

The TLS at the Chelsea Flower Show

Briefly to the Chelsea Flower Show: where I had learnt that there was a 'literary garden'.

Briefly to the Chelsea Flower Show: where I had learnt that there was a 'literary garden'.

There was a picture of it in the office when I was picking illustrations for the TLS this week.

Every other newspaper seemed to have its own garden at Chelsea.

So why not the TLS? We could adopt a garden It would need only to be a small one.

Not, I think, however, this literary garden - despite its

Cornus Kousa tree called 'China Girl' and geraniums called 'Jolly Bee'.

The lettering on wood and slate was magnificent; the literary was not.

But then I thought of the arguments that we would have to have at the TLS about what words would be most truly worth the skills of master carver, Martin Cook.

Donne vs Dryden. Shelley vs Shakespeare. Our own poets vs each other.

Enough, enough. No sponsored horticulture for us.

Time to move on — to the 'show gardens', larger constructions sponsored by DIY chains as well as newspapers, financial power-houses and northern cities where water was once the important source of power.

Crowds gathered five deep around a 'gold medal winner' based, it was said, on Roman ruins in a city of eastern Libya, one now judged to be in the good part of that benighted country. No one seemed to know why they were looking so keenly. The relationship to Ptolemais was not as evident as I had hoped. The beauty was said by some to be something to do with parsnips.

Inside the main tent there were flowers shown without the assistance of human invention. There were walls of daffodils, squares of grasses, bamboo groves, parade grounds of delphiniums and lupins,; and there was a bright giant lily called Nuance (surely an irony that would have graced a truly literary garden) whose bulbs were for sale at £5 for three (from www.hartsnursery.co.uk). Two packs have come home here tonight.

Maybe they will produce their pink-striped bigger-than-any-lily-I-have-ever-seen blooms in Primrose Hill as well as Chelsea. More likely they will not.

It is an axiom hard to deny that gardening is all about hopes and dreams. The greatest proof of visitors' rejection of gardening reality was the sight today of all the lawn-mower sellers, keen men in brazen sun glasses, keen women in black pencil skirts, all of them ready to sell cutters of grass at unrepeatable cut prices, all of them reminders of gardening as it is, all of them avoided like blight.

May 20, 2011

My smallpox friend remembered

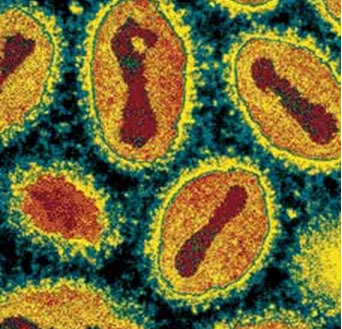

When I visited one of the last surviving smallpox viruses — in Atlanta almost exactly twenty years ago — it had its own name.

When I visited one of the last surviving smallpox viruses — in Atlanta almost exactly twenty years ago — it had its own name.

It was called Harvey.

I was there because this final member of a near-extinct species that has lived with mankind for more than a million years was about to be put to death. Harvey and his 100 remaining relatives, including a Mrs King, a Japanese cousin called Yamamoto and a South American known as Garcia, had lived quietly together for the past ten years but time, I was told, was running out on one of the world's highest-security death rows.

There was an "autoclave" chamber ready to carry out man's first deliberate "species-cide". There was no international outrage. Environmentalists were not battering down the computer-controlled doors at the Centers for Disease Control. Greenpeace was not planning a rescue. Smallpox viruses like Harvey had few friends.

But like many on death rows throughout America all these members of the Variola family, one of the most virulent killers in history, are with us still, still awaiting the results of their latest retrial.

Harvey's family was declared extinct in the wild state thirty years ago after an eradication campaign by the World Health Organisation. The few remaining captive specimens were then gathered into two laboratories, in Moscow and in Atlanta, where a final simultaneous roasting was planned to take place in 1993.

Great ceremony was expected when the disease finally joins the dodo. The day was to be presented as a triumph for superpower co-operation and the New World Order. But it never happened.

There are many explanations for this, some political and some scientific.

But, even back in 1991, down where the final deed was to be done, a few doubts seemed to be growing.

On its concrete surface, Atlanta was (and is) a brash modern city where the only direction is forward, where even the trees are sponsored by Coca-Cola and every television seems permanently tuned to hometown CNN. But within the dark red earth blow there lay (and lies) an old Atlanta of fundamentalist Christianity and philosophical scepticism. Perhaps most important, there lay (and lies still) the Atlanta of Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit, the characters that made the city famous for dreams long before cable television and Coke Classic came along.

Uncle Remus's creator and alter ego, Joel Chandler Harris, an Atlantan journalist, could not see an animal without anthropomorphising it into a children's friend. The handwritten notes for his famous allegorical tales, left behind on his death in 1908, fill a large library store (also paid for with Coca-Cola cash) barely a few hundred yards from the Centers for Disease Control. What, his admirers then asked, would Harris have made of this extermination business?

Uncle Remus's creator and alter ego, Joel Chandler Harris, an Atlantan journalist, could not see an animal without anthropomorphising it into a children's friend. The handwritten notes for his famous allegorical tales, left behind on his death in 1908, fill a large library store (also paid for with Coca-Cola cash) barely a few hundred yards from the Centers for Disease Control. What, his admirers then asked, would Harris have made of this extermination business?

In his stories of battle between the weak and the strong, would he have made us love Brer Pox as well as Brer Fox?

I met Walter Barrow, a Baptist lay preacher in a cream synthetic Panama hat and an enthusiast for the lost world of Uncle Remus. "Smallpox is no good to anyone but to destroy the last one of God's creations why do we need to do that?

What harm is it doing where it is? That is what Mr Harris would have said.

"Hundreds of years ago", Barrow drawled at me, "we thought we had God's will to destroy every wolf or bear we could see. It was up to us. If we could have exterminated them, we would have. Now we do not think that way. Do we know how we will feel about smallpox in the future?"

Donald Hopkins, a former scientist at the Atlanta centre, had already written his book in which smallpox is the central character, showing how its distinctive brick-shape viruses, invisible until the invention of the electron microscope, struck Stuarts and Habsburgs, Americans and Aztecs and eliminated 10,000 Bihari Indians in a single month as recently as 1974.

He claimed not to be worried about losing the hero of his history, but was deeply concerned, he said, about man's hubris in destroying the last virus.

"We cannot know the future", he said, "and we cannot justify destroying something that could be of enormous value to us in decades to come, valuable in ways we cannot even conceive of now."

Dr Brian Mahy, who then lead the virologists in Atlanta, was impatient about such objections. Smallpox was for him a rare eradicable evil.

Unlike rival viruses, such as chicken-pox and herpes, Variola does not remain permanently in its victims. That made it unusually vulnerable to new methds of vaccination, containment and elimination in the wild; so man suddenly had the chance to remove its threat entirely.

Mahy recalled his horror 13 years before on learning of the still unexplained infection of Janet Parker, a Birmingham photographer, who was working near a secure smallpox laboratory and became the world's last victim. His ambition was to remove even the possibility of accident or terrorist theft and to transfer his workers to new tasks.

He wanted not only to destroy all the world's smallpox viruses (dismissing suggestions that the devious Soviets might keep a bit back), but to destroy the non-infectious DNA building-blocks of the disease.

He feared that if the DNA were kept for research, some fiendish scientist of the future (possibly the fairly near future) might join it to a harmless relative, such as the smallpox vaccine Vaccinia, to produce a new and dangerous epidemic monster.

The very air in the building encouraged fear: or so it seemed to me. Constantly scrubbed and rescrubbed clean, it passed down into the most dangerous areas through red-coiled lines that hung, like snakes, ready for attachment to sealed plastic suits which the workers wore.

Nobody liked to go beyond the slightest normal procedure. When we entered the inner chamber where the viruses were kept, even the unit manager took one look at the chained-and-padlocked fridge (bound with grey masking tape and unopened for many years) and said he wanted to stay there "as little time as possible, please".

Few journalists had ever been shown it before, Mahy said.

I therefore recorded that apart from the chain-bound fridge, which was silver and blue and would suit a security-conscious serial killer, room 318B contained nothing but a box of Kimberley tissues.

The only excitement planned for the near future was for Garcia, Harvey's South American friend, to be given a brief reprieve from his frozen state, to be warmed up, passed to the care of Janice Knight, a space-suited biologist, and allowed to grow on some monkey cells, bred on a piece of human tissue, before transportation to Moscow.

Mrs Knight and her Russian colleagues hoped that before smallpox was extinguished as a living species, its biological characteristics could be fully mapped by computer. Harvey, named in 1944 after a British nurse who caught the disease from a soldier in Gibraltar, could, for example, be reduced to an 180,000-long list of the nucleotides known to scientists as A,G,C and T.

Smallpox would then be able to be kept in a book instead of a fridge. As long as the correct order of letters had been recorded, the remote possibility of a future Harvey outbreak whether caused by Soviet cheating, an unlucky grave robber, or a neglected African test-tube could be rapidly verified and countered.

I passed on to Mahy some of the worries of Barrow about man playing God with another species. If by some peculiar turn of fate the roles of man and virus were reversed, I asked, how long a list of letters would it take for man's DNA sequence to be recorded?

About 100 million, he guessed. Would that mean that we, too, could be responsibly removed from the world?

Dr Mahy smiled and went back to his world of rationality and white coats.

For Barrow, standing outside Harris's house at "The Sign of the Wren's Nest" it was not much of an answer. "Better not mess with Brer Pox. That's all," he said.

It seems that Mr Barrow won. As I understand it now, writing from faraway London, a decision on the latest trial is awaited shortly.

May 15, 2011

Lara Croft and me

On Facebook the past can become the present with alarming ease.

On Facebook the past can become the present with alarming ease.

An old friend (or rather a young friend whom I have known for a long time:thanks Ed) has posted a reminder of my afternoon a decade ago with the virtual explorer, video-game icon and 'spokesmodel' Lara Croft.

It is one of those reminders that in darker moments one may think will alone survive when every other record of one's existence has vanished.

I am certain that when my esteemed Times colleague, Keith Blackmore, first suggested that I be interviewed by Lara, I had no idea of whom he was talking.

I may have affected some knowledge. It was wise for newspaper editors in those early electronic days to pretend familiarity with computer games which one's children, while playing them with enthusiasm, were unlikely to share with their parents.

But I am sure I knew nothing of the character whose creators had decided to write a King Tut scene into her script.

So her script became my script. Yes my script - unless anyone watching now might think that the Editor of The Times ever spoke to anyone, even the most renowned female Indiana Jones in cyberspace, as he now appears to have done.

May 10, 2011

Good homes wanted

Last weekend I was clearing bedrooms and studies for the pitiless attention of builders, reminding myself of the years when I could never pass a junkshop without coming out with a set of the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica or the complete Mark Twain, recalling how in the 1990s libraries went suddenly out of fashion and the result that so many good books were suddenly in search of a good home.

Last weekend I was clearing bedrooms and studies for the pitiless attention of builders, reminding myself of the years when I could never pass a junkshop without coming out with a set of the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica or the complete Mark Twain, recalling how in the 1990s libraries went suddenly out of fashion and the result that so many good books were suddenly in search of a good home.

I now have only three sets of the great 1911 encyclopaedia, having found a grateful new owner for one fine sequence in green cloth. I have walls of brown Oxford Classical texts which are convenient for browsing only the obscurest texts unavailable elsewhere. But at least they were all saved from the junkyard - and, along with Twains and Pepys and Kiplings and Anglo Saxon Chronicles, will be saved again despite the more practical use that could be put to the space.

Hence the horror just now when our esteemed colleague, Catharine Morris, revealed the shame of her Sunday shopping trip near East London's Columbia Road flower market. While I was beside the Berkshire Thames packing past follies, she was downstream finding new ones. In Ezra Street (Sundays only) the history of the TLS is for sale - amid chintz and china company which we surely never deserved. Some ingrate insitution has cast out our ancestors' labours, their noble reports on Books in Basutoland and Eastern Romanity, among crockery and worse.

But now the builders are upon me. Will no one else give these friendly volumes a good home?

May 3, 2011

Torture in Tripoli

Miss Tully was the sister — or possibly sister-in-law — of the British Consul in Tripoli at the end of the eighteenth century.

Miss Tully was the sister — or possibly sister-in-law — of the British Consul in Tripoli at the end of the eighteenth century.

She lived through years of Libyan revolution, systematic torture and macabre assassinations but, if returning to the capital today, would surely feel aggrieved at the decline in standards of public safety.

The Gadaffi of Tripoli in her time was called the Bashaw — and Miss Tully's letters home about his court provided the first account 'of the private manners and conduct of this African Despot'.

As readers of its first edition in 1816 were told, it also detailed 'such sketches of human weakness and vice , the effects of ambition, avarice, envy and intrigue as will scarcely appear credible in the estimation of a European'.

A woman's walk on a garden wall might be fatal, the bite of a camel even more so, an invitation to take the long indented corridor to the Bashaw's dining area absolutely so. There were catastrophic plagues and calamitous white slavery.

But there were many compensations. There was no oil then — but gold could be found on the beach and 'tied in bits of rag about the size of a small nut', each one worth ten shillings and six pence. There were transparent candied dates, 'far surpassing in richness any other fruit'. A lucky guest who pleased the Bashaw might be given a piece of Roman paving.

The rules of mourning dress after each bout of plague or murder required that golden finery be dulled and dampened rather than exchanged for black. But this was only a small inconvenience. To read on through the delightful new edition of these letters, published by Hardinge Simpole, is the purest nostalgia.

April 26, 2011

Boadicea's remains

After reaching a certain age we should maybe review all the little truths that we regularly pass on to others - just in case they are not true.

After reaching a certain age we should maybe review all the little truths that we regularly pass on to others - just in case they are not true.

Take, for example, the thick layer of ashes from Boadicea's burning of London which I would mention from time to time when walking past All Hallows by the Tower during my days at The Times.

I was sure it was there. I was sure I had seen the black remains. I would describe them with by best antiquarian enthusiasm.

And then a few weeks ago, waiting for some incomprehensible meeting about money in a City office, I dropped by to see Boadicea's ashes again.".

Nothing of the kind was immediately visible. I asked where the ashes were.

Just before the weekend, in an email from the vicar's helpful assistant Angie Poppitt, I received the following news that:

"in the undercroft can be seen the tessalated pavement of the house of some Roman Londoner; while seven feet beneath the level of the present building there were found the ashes of the London sacked and burned by Boadicea in AD61."

Ms Poppitt "would presume from this reference that evidence of the ashes was found during the archaeological excavations of the crypt in the 1920s, but that they were covered over again once the work was completed. If that is the case, they would now lie beneath the present crypt floor which is, as you may recall, several feet lower than that of the Roman pavement behind the glass".

Tactfully she points out: "It may be that someone mentioned this fact on your earlier visit, and this is what you remembered".

Even more tactfully she suggests that "it may be that there are more detailed references to the ashes in the archives or in the Museum of London's records of the excavation, but I have checked with our present tour guides and, whilst many of them do refer to Boadicea when they are talking about the Londinium model and the artefacts, none of them have any knowledge of the evidence of burning actually being visible in this church".

All similar points in my conversational armoury are under current review.

April 19, 2011

Hoi Polloi and whores at sea

This dilatory blogger (apologies for that) spent the weekend in sunny Durham at the Classical Association, partly in order to hear the presidential address by Christopher Rowe on the relationship between Plato and Socrates - and to consider what next year's President (your same TLS blogger) might contribute in his turn.

This dilatory blogger (apologies for that) spent the weekend in sunny Durham at the Classical Association, partly in order to hear the presidential address by Christopher Rowe on the relationship between Plato and Socrates - and to consider what next year's President (your same TLS blogger) might contribute in his turn.

After introducing us to a man called Plocrates and delivering a powerful Platonic coda on the general purpose of scholarship, Professor Rowe provoked some college bar discusion on the topic of Hoi Polloi. In Plato's view, it seems, these were not primarily the great unwashed, the pullers of oars and heavers of water; Hoi Polloi were most of all the rich and powerful men who saw no benefit in a broadening and deepening education at public expense. The President in his masterly address did not name names from our own coalition times; but afterwards amid the Durham ales there was less inhibition.

If I had been asked on the northward train about 'naval imagery' in Greek epigrams, I would not have got much past 'the ship of state' - despite spending more than usual time this year in the Greek Anthology. On the southward way home, I could have chatted happily about how Alsclepiades' 'twenty-oared cargo ships for ship owners' (AP5.161) represented elderly prostitutes who took 20 men in a day and whose piracy of mens' purses left clients more ruined than castway sailors.

So thanks to Maria Kanellou of UCL for that - and for discussing how for Meleager (AP12.157) the magnitude of the ocean meant 'an open sea of boys of every race'.

April 6, 2011

'Jordan Codices' just another fake from the souk

There are few subjects on which the media is more carelessly gullible than ancient archaeology. Reporters trained to check claims and counter-claims as a matter of dull, daily course, fall time after time for publicity-seeking pretenders, or fund-starved chancers claiming to have discovered the authentic face of Julius Caesar or lost bits of the Bible story.

There are few subjects on which the media is more carelessly gullible than ancient archaeology. Reporters trained to check claims and counter-claims as a matter of dull, daily course, fall time after time for publicity-seeking pretenders, or fund-starved chancers claiming to have discovered the authentic face of Julius Caesar or lost bits of the Bible story.

And so, to no surprise at all, it came to pass with the lead tablets the size of credit cards proclaimed as biblical secrets by the BBC and almost everybody else last week.

Yes, of course I know how facts can spoil a good story but please.

How hard could it have been to find the people who knew that these objects were just one tiny part of the massive fake-mountains of the middle east?

That means people who know about Greek inscriptions (we still have them) and not enthusiasts for Christian entertainment.

Peter Thonemann in the TLS this week explains briefly and patiently why.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers