Peter Stothard's Blog, page 86

November 18, 2010

Hibiscus night

There is that dread (I've always felt it) of the waiter who wants to tell you what to eat.

There is that dread (I've always felt it) of the waiter who wants to tell you what to eat.

In America the 'specials' are so often to me a special horror, delivered with menace by men who should surely have something better to do.

That is what I thought when I first met them and their wares thirty years ago. And I still think that - though it is not usually polite (no, not ever polite) to say so.

This week I had my first experience of what maybe many restaurant eaters always feel, the explanation of what I might eat by someone who lightened the experience instead of darkening it.

The place was one called Hibiscus, which I now discover is a much regarded eatery, just off London's Regent Street.

I am not qualified to praise the food itself, although the intensity of the tastes is still here now, of ceps, nuts, berries and smoke from an Autumn menu which seemed uniquely ( to me) worthy of the seasonal name.

What I can report more confidently was the Ariel performance of the man who told us what we were eating - so delicately that we hardly knew he was there except in the puff of his words.

He even told us how we should eat -, how deep the spoon should dip in to the eggshell of forest things.

We were with the dearest of old friends - and it would be wrong to leave readers with the notion that the meal itself was anything but dear too, the word once used for 'expensive' though less so now.

Worth the money?

Yes, I would say so - and not least, maybe mostly for me, for the way in which the light words of a waiter showed how so many had done it so heavily before..

November 15, 2010

XXXXX for Evolving English at The British Library

I have now had three separate experiences of the magnificent British Library exhibition, Evolving English, which tells the story of our language from the Undley Bracteate to the Tok Pisin.

I have now had three separate experiences of the magnificent British Library exhibition, Evolving English, which tells the story of our language from the Undley Bracteate to the Tok Pisin.

The first was for what we call at the TLS 'the topical', the short piece with accompanying picture which we publish on Page Three each week, sometimes marking an event in the news, more often a cultural event which we think our readers would like to know more about.

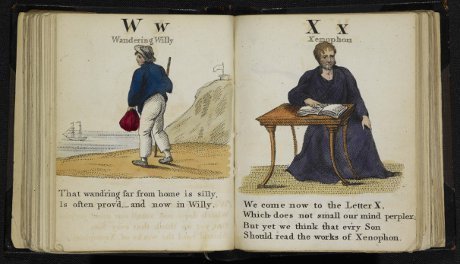

On November 5th I chose a selection from The Paragon of Alphabets (1815) in which S stood for Sorrowful Simon, T for Timid Tabitha, W for Wandering Willy and X for Xenophon.

The choice for X, I thought, was something of a surprise.

I could see that by the time a diligent schoolboy reached the end of his nineteenth century alphabet book he might be desperate to Wander from his home and classroom for a while. So an admonition to avoid the fate of Willy would have been well placed.

But the next entry, we mused, could surely have risked confusion, since X is for Xenophon, the Greek writer justly famed for imprudent Wanderings (401–339 BC), in the failed cause of putting a new king on a middle eastern throne.

The author of the Anabasis, while not exactly a 'silly' Willy, was certainly a chancer, an uncertain role model unless maybe the text-book writer was thinking about Xenophon's other famous tome, the so-called Cyropaedia, on how best to educate a benevolent despot.

Last Thursday night I visited the show at its opening. As I could now read in David Crystal's masterly catalogue, X was notoriously perplexing for Alphabet Book writers in the age before the Xylophone or the X-ray. Xenophon would today, he thought, be an unlikely candidate, an absence only partly due to the decline in classical classes for the very young.

Last Thursday night I visited the show at its opening. As I could now read in David Crystal's masterly catalogue, X was notoriously perplexing for Alphabet Book writers in the age before the Xylophone or the X-ray. Xenophon would today, he thought, be an unlikely candidate, an absence only partly due to the decline in classical classes for the very young.

An exhibition opening is an excellent time to meet old friends and discuss the problems faced by universities, museums and libaries in the current era of govenment spending cuts. But I didn't mange to do any justice to the exhibition itself; indeed I felt unreasonably impatient that it was showing its glories too quietly and with insufficient pzazz (where did that word evolve from?).

On my third engagement with Evolving English - today and not too hard since our TLS office is only half a mile away - I finally found why everyone who cares about English should try to come there before it closes on April 3 next year.

It is a triumph of explanation of 1600 English years - aided by David Crystal's catalogue that begins with that Undley Bracteate ('the earliest clear example of several words in Old English' on a gold medalllion, AD 450-480) and ends with Tok Pisin (a 'pidgin talk' recipe for Tamato Sos,1964) and a poem by John Agard (1985) in which a man is unjustly accused 'of asault on de Oxford dictionary'.

November 9, 2010

James Ellroy's partner writes - and other surprise responses

Today is press day at the TLS - and as usual one of the Editor's greatest treats is reading the final proofs of the letters page. Anyone curious to know the family connection between a well known female Radio One broadcaster and the author of the French 1913 classic, Le Grand Meaulnes, should read this week's issue.

It is sometimes said by carpers that the on-line comments on newspaper websites struggle to match the standard of those in print. So let me also draw attention to the surprising (and, to use old press language, exclusive) comments by Erika Schickel, the partner of the American writer James Ellroy, on our review of Ellroy's The Hilliker Curse.

See too the moving responses to William Dalrymple's review of the letters of Bruce Chatwin.

And although Elaine Showalter's provocative reading of James Ellroy has been justly popular, its attraction has been far exceeded among on-line readers by Robert Pott's lapidary account of J.H.Prynne and the notoriously difficult poets of the Cambridge school.

November 8, 2010

Get the NETs! Support World NET Cancer Awareness Day on Wednesday

In my inbox today sits a note about World NET Cancer Awareness Day.

In my inbox today sits a note about World NET Cancer Awareness Day.

It is there because a decade ago I was given no chance to escape one of these nasty little killer NETs, a Neuro Endocrine Tumour that had settled in and around my pancreas.

The cancer was diagnosed late and I was fortunate then, beyond all odds, to find eventually the medical men in America and Britain who managed to destroy Nero (my name for my tormentor) just before Nero would have destroyed me.

Late diagnosis, I see, is the theme of this first day aimed at raising international awareness of NETs. "If you don't suspect it, you can't detect it" is the motto. Ninety percent of NET patients, it seems, are initially treated for the wrong disease, and a correct diagnosis takes an average of 5 -7 years after symptoms first appear.

Too often that is too late. I have clearly etched pictures in my mind of the fellow patients I met in 2000 for whom diagnosis, when it came, could not stop their deaths.

The force behind the British arm of this campaign is the tireless Cathy Bouvier, a NET nurse specialist who, when I first met here, was working with the pioneering professor, Martyn Caplin, at the Royal Free Hospital in London. Her charity, the NET Patient Foundation, has in the last year offered information and advice to more than 20,000 patients and their families.

Sometimes dangerous diseases are undetected through lack of symptoms. I am no doctor myself but In my case, I can say, there were plenty. At the end of this blog I'm going to attach a short extract from On the Spartacus Road, a book I wrote two years ago, which, while not itself about cancer, contains my best and most indestructible memories of what the symptoms were like.

Sometimes diseases are undetected because busy General Practitioners, with too many patients and too little time, fail to identify the symptoms. That was not a factor in my own Nero's survival at all. Some of the most distinguished consultants in the country looked at his effects and offered only bland diets and ignorance.

So, all power to all everyone working for World NET Cancer Awareness Day on Wednesday.

Anyone with any cause to wonder whether they should visit the campaign's website, should do so. Click and see.

The following is from On the Spartacus Road (2010), published in the UK by HarperPress and in the US by Overlook Press. The chapter is written on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius and is part of the battle scene in which Sparatcus first defeats his Roman enemy.

The following is from On the Spartacus Road (2010), published in the UK by HarperPress and in the US by Overlook Press. The chapter is written on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius and is part of the battle scene in which Sparatcus first defeats his Roman enemy.

"A decade ago, in the hours when I was in the heaviest unexplained pain I used to see sometimes battlefields like this one. I was never quite sure why. When a biting, bruising clash of enemies was happening below my ribs, it maybe made a certain sense to imagine other battles of blood and guts. Perhaps the free mind has its own way with a blasted body, its ways to make the time pass by, regularly some nine hours of time between the first sense that my Nero was stirring (the name was a classicist's joke at first) and his retirement from the flattened field.

Only every few months did these horrors come, but once they had begun each time they were inexorable and followed the same absolutely predictable course. Although I would later describe the pains to doctors in lurid but wholly unsuccessful detail, I never mentioned the palliative pictures. It was hard enough to get a medical answer without seeming like a late-night history channel. It took years to discover that Nero was a large lump of cancer. During that time the pictures became the most memorable part of the experience. Looking back from this wooden table half way up Vesuvius, the battle scenes seem certainly the only part worth remembering now.

The subjects then were never ones I deliberately chose. To attempt have reconstructed the ancient suddenness that happened on these volcanic slopes would have been absurd. Any truth of Spartacus's first battle has long lain far beyond the power of recall or reason. The facts are still far beyond even the wildest argument. There is nothing solid surviving of the battle between Glaber and the gladiators, no swords, no wine-flagons, no words.

The pain pictures were a different experience altogether, random, like a roulette ball cast into the wheeling rays of the sun. Scenes from a classical education came without will. During some of Nero's visits I had vivid views of this first fight in the Spartacus war, not those of a general watching high up on a nearby hill but of a soldier seeing what was close before his eyes. It was as though I had been at the centre of this and other slaughters, hour after hour after hour.

This Vesuvius scene was one of the commonest, an assault of iron on the upholstery of my stomach, ribs grasped like ladders, alien objects left behind, broken glass, blunt knives, wave upon wave of pain, slow like an hour then blurred like a second, warfare in its unique and maddest way. After the first hot attack there came shivers and stabbing icicle shards. After the nausea of fear came the thud of the drum and the muffled horn. I might face a baton-wielding field officer. I was suddenly one of 'the wretched wounded', begging to be hit on the jaw by a drunken field-surgeon or any decent man administering the battlefield anaesthetic of his age. The aggression was grotesque. What was it all about? Such violent pain had to have some progression. It had to be saying something. It could not be without some cause or purpose.

As the dust and confusion cleared, a more organised picture show was presented on the surface of my skin. My body pumped up tight, as though with poisoned liquids and gases, the fluid components of pain. Then, on the tight surface of this slowly expanding balloon, as though from some image-projector above, appeared all the peculiarly recognisable scenes, the ladders clinging to the rocks, the climbers, the killers, the escapers, the men who killed themselves to avoid torture by the unknown. I was not hallucinating. These were more like memories than fantasies or dreams. As my stomach seemed to grow, so the pictures on it grew too and spread further apart. Then smaller images became visible, things I could not see before, people beyond the battle site on the mountain, watchers on other slopes, in the skies, in distant cities. Then the balloon subsided, briefly restoring proper proportions before shrinking into a jumbled mess.

There were no ill effects next morning. My mind was often quicker and clearer after the chaos had passed. Poets have often claimed that opium sharpens their thoughts. Perhaps pain too releases its sharpeners into the bloodstream. Perhaps the poetic drive comes not from the drug at all but from the pain which the drug is supposed to dispel? Are drug and disease in that respect the same? These questions and the shows continued until one of my long line of doctors identified both the cancerous cause and the impossibility – after so long – of doing anything to remove it. At that point the days of imagination were over. My days of argument and forensic medicine began, none of that of any relevance now on the Spartacus Road."

October 29, 2010

Nick Clegg's island

Nick Clegg, our Deputy Prime Minister, was 'the castaway' on Desert Island Discs this week. I only heard the end of the Friday repeat - where he was asked about the one book 'apart from the Bible and Shakespeare' that he would take with him for the period of forced isolation that so many in his own Lib Dem party would like to see.

Nick Clegg, our Deputy Prime Minister, was 'the castaway' on Desert Island Discs this week. I only heard the end of the Friday repeat - where he was asked about the one book 'apart from the Bible and Shakespeare' that he would take with him for the period of forced isolation that so many in his own Lib Dem party would like to see.

'The Leopard', he promptly replied. The questions have been the same on this show for decades so he knew he had to have a name ready.

By Lampedusa, he added, halting slightly over the pronunciation. Since Mr Clegg is famously multi-lingual, this was perhaps to reassure the listeners that he is a true man of the British people.

He told us that he had recently reread it - and enjoyed it as much the second time as the first. So it would be the perfect book for further re-reading when he was faraway from the hurly burly and no longer supporting David Cameron in policies which most of his party members came into politics to oppose.

'It's set in Sicily, I think', he added.

He thinks?

He's read it twice and he only 'thinks' it is set in Sicily.

No wonder he still feels it has hidden insights which only desert island concentration could provide.

Meanwhile he will certainly enjoy the forthcoming Alma Books volume of unpublished letters from London by Lampedusa, which is to be reviewed soon in the TLS.

October 26, 2010

Simon Hoggart's wonderful Long Lunch - with W.H. Auden, Kudu Piss and a Gorilla

Last night could have been a terrible night - for all sorts of reasons not quite right for a blog or, at least, not right quite now.

Last night could have been a terrible night - for all sorts of reasons not quite right for a blog or, at least, not right quite now.

But I had Simon Hoggart's book of episodic memoir, A Long Lunch, to read. Christmas is coming (and there is still Halloween to be survived) and if any friend, you think, needs a lift, this present will not disappoint.

Hoggart is the political sketch-writer for The Guardian. For American readers unfamiliar with the role, it is the one long filled at The Times by Frank Johnson (see my review of Best Seat in the House from last year). Sketch-writers tend to be the wisest as well as the wittiest of political writers - and Hoggart has been Johnson's successor as doyen of the trade.

Last night it was the non-political passages that cheered the most, the Martini recipe which WH Auden gave him as a child, the journey by which the name Death Cab for Cutie left the pen of his father, the literary critic, Richard Hoggart, and ended up, via the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, as a cult act on the American West coast.

There is minimal comment on the cult bands but Auden, it seems, slightly disappointed the Hoggarts by drinking the bottle of wine which in those days was thought quite enough for table of three - as well as the bottle of gin into which the young Hoggart had mixed the necessary thimble full of vermouth - and then concentrating his conversation on the virtues of the Kenwood Chef food mixer. He was, however, gracious in using greaseproof paper to copy the Observer crossword so that the Hoggarts could enjoy the puzzle after he had left.

Rare cocktails of Africa are lovingly described, including the Gorilla (take one inch of orange juice in a pint jar, add beer to within an inch of the rim, top up with whatever spirit is indicated by a coin thrown at random behind the barman and enjoy) and Kudu Piss, a flourescent brew made of Rhodesian pastis and American green cream soda (it really does glow in the dark).

The world of journalism (as to all great journalists) remains a mystery to this master of its arts being, as he puts it, 'similar in many superficial ways to the real world, but also deeply different, rather like those planets the Star Trek crew visit, in which the atmosphere is identical to ours, and for some reason everyone speaks English, except they breathe through gills or have purple skins'.

And all that before we get to Margaret Thatcher and the Princess of Wales and what (I don't yet know what) Alan Clark said about Melvyn Bragg.

October 20, 2010

YMCA - A!

On the last night of what seems a long journey selling the virtues of the TLS (and some copies of Spartacus Road) I am at JFK airport watching on TV the same baseball match I was watching last night at Yankee Stadium.

I don't know anything much about baseball (as I type, the Yankees are 'coming back from the dead' but that is merely the view of the man next to me at this computer-stacked bar). What I remember most from last night in the Bronx is the singing, which includes a rendition of that gym-dance song YMCA, at a moment both predetermined by tradition and not quite clear to me.

I'm pleased that Deborah Porter, the glamorous chair of the triumphant Boston Book Festival, has deemed our discussion of Spartacus, Cleopatra, Achilles and other movie-star ancients to have been 'one of the most popular sessions that people were raving about'.

That was 'a pleasant surprise'. she told the Boston Globe.

At the end of this journey I am not quite so surprised as Deborah was.

One of the lessons to me from the last six weeks - from Wigtown in Ayrshire to Henley on Thames, from Cheltenham, Gloucestershire to Boston, Massachusetts and Bloomsbury - is how great is the modern passion for engaging with the ancient world in different and surprising ways.

Wow! The Yankees are even further 'back from the dead', 5-0 ahead, and in stadium that is only one colossal, colosseal reminder of what today's warriors owe to the past.

October 18, 2010

Byron buys the TLS

This picture is the proof (courtesy of our commercial director, Jo Cogan, left) of the great TLS Boston Book festival subscription drive.

(Or it would be if I could upload it from my machine: full picture-service may have to wait; for the time being just imagine the picture, big TLS banner, Copley Square grass, hundreds of enthusiasts at a wonderful free festival of books)

With the help of our T-shirted team (thanks everyone) we handed out copies, met current subscribers and signed up new ones.

The editor will forever have a special thought for the new lady subscriber who accepted our offer of a free signed copy of my Spartacus Road on condition that I inscribed it to her accompanying dog, Byron, who, it seems, normally prefers science fiction but was prepared to make an exception on Saturday for the TLS.

Almost as surprising was the promotional picture for the festival in the back of the cab from the airport which showed the face of my old friend and former foreign secretary, Robin Cook, as a star writer of Boston.

The face on the screen was very clearly the man from faraway Scotland who resigned from Tony Blair's cabinet over the Iraq War and died shortly afterwards although, as in the case of the TLS-selling team, you will have to take my word for it.

There is, however. a Boston writer called Robin Cook who writes novels about reassembling body parts. His most famous is called Coma. I wonder if he knows how reassembled he has become this week in the back of Boston cabs.

October 12, 2010

Whisky for parents: Latin for all

It was the sight of the Highland Park promotional team handing miniature scotches to the parents queuing for Jacqueline Wilson which made the first weekend of the Times Cheltenham Literature Festival so memorable.

Well, one of the things, anyway.

While audiences inside the tents were being swayed by the severest novelists and historians, the line for entry to the child-world of Ms Wilson was like a character in a fantasy itself, long, snaking, mostly young and patient and fortified, at the older age levels, by plastic cups of what I'm told (not being a whisky drinker) is a most magnificent malt.

Thanks to Mary Beard, who has already described some of our classics events, the words of 'laudabunt alii' and 'odi et amo' were displayed on large flashing screens over the scotch lawn. A friendly crowd came to hear me talk face to face about Spartacus Road with Ramona Koval who normally I talk to only over thousands of miles of air and sea on the ABC Books Show in Melbourne. The poet Statius, who has a starring role in that book got a decent vote in the Ancient Booker: since, of all the writers on the short-list, he was the one who most cared about winning prizes, he would have been disappointed with his champion, I am sure. So, sorry, Stace (the name by which Chaucer knew him).

Tonight we have the real Booker. And tomorrow with the TLS and Spartacus Road to the Boston Book Festival, boosted (lest even without whisky excess I might begin to flag) by a very welcome review by Frank Wilson in the Philadelphia Inquirer today.

October 7, 2010

On the Bloomsbury to Boston via Cheltenham road

In a few hours Mary Beard and I will be talking about On the Spartacus Road at the British Museum before heading off to the Times Cheltenham Literary Festival where Mary has organised an impressive range of classical events.

In a few hours Mary Beard and I will be talking about On the Spartacus Road at the British Museum before heading off to the Times Cheltenham Literary Festival where Mary has organised an impressive range of classical events.

There is going to be a mass class in reading Catullus and Horace in Latin (not the usual literary festival fare) and various of us fighting (not illustrated here) about who would have won a rather widely construed 'Ancient Booker Prize'.

There will be Spartacus Road again too - with Ramona Koval of the Australian ABC Book Show. And after that the TLS, this time without Mary, goes to the American East Coast for the Boston Book Festival, meeting readers as well as discussing history and myth, Spartacus and Achilles meet Cleopatra as it were.

If I get to the BM early enough tonight, I'm keen to stop by again at one of the most extraordinary discoveries in Britain in the past twenty years, the collection of late Roman gold and silver known as the Hoxne Treasure, found in a Suffolk field in 1992 by a man with a metal detector who was looking for his friend's hammer.

This week in the TLS Kenneth Lapatin elegantly traces our changing attitudes to the very word "treasure" while reviewing the BM's newly published account of the massive hoard of coins, condiment-holders, jewellery and toothpicks once carefully stored by a wealthy family in the years before Roman power faded and fell. Among routine inscriptions of Christian piety is the hope that the recipient of a "stunningly pierced gold bracelet" may "use it and be happy". We may even know the owners' names – although one of them at least seems to have been very strangely spelt.

The "friend's hammer" has not been discarded. It is displayed in the museum as a significant part of the discovery, its context, something from a later time that illuminates the meaning of what came before. Such application of 'reception theory' is not popular with all visitors. Although the central "battle to establish reception as a legitimate, indeed essential, part of Classics has long been won", there are constant skirmishes about what is truly relevant and useful and what is merely fashion. I suspect we may face some of the same issues in Cheltenham and Boston too.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers