Peter Stothard's Blog, page 80

November 2, 2011

Samuel Beckett's disease

"Full house every night", the author of En Attendant Godot noted in 1953, in a letter to his lover; "it's a disease."

I'm quoting here from the second volume of The Letters of Samuel Beckett, which is reviewed in this week's TLS by Alan Jenkins, the deputy editor. It tells an extraordinary story, and, for those who'd like to read more about the transformation of Beckett's reputation, his thinking and life ("In the place where I have always found myself, where I will always find myself, turning round and round, falling over, getting up again, it is no longer wholly dark nor wholly silent"), the review will be online, all being well, later today.

But there's more . . . . To quote from David Horspool's introductory note to this week's TLS:

"The physical demands that Samuel Beckett's plays make of their actors are well-known. In Play, the characters are made to stand inside urns, as pictured on this week's cover. Beckett was very particular that only standing, not sitting, would do: 'The sitting posture results in urns of unacceptable bulk and is not to be considered'. In Endgame, a couple are confined to 'ashbins', while in Happy Days, Winnie is embedded, eventually up to her neck, in a mound of earth. The symbolic and metaphorical underpinnings of all these confinements have been the stuff of Beckett studies for years. Peter Leggatt, in turning his attention to a script in the playwright's archive that is a progenitor of Play, has found an unlikely new source of inspiration: chicken-farming. In Commentary, Leggatt explains how the manuscript of 'Before Play' – previously referred to but never before quoted from or discussed by scholars – makes use of images of flight to contrast with its three confined characters, who are kept not in urns, but in white boxes, with their heads poking out."

October 28, 2011

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 4

You know how it works by now – at least, you know how it works if you've read this, that or the other. A fiver, a bookshop and an attempt to escape the customary seasonal shite . . . .

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part IV. The hebdomadal challenge is to find a neglected work or curiosity by an established author in one of London's secondhand bookshops, for about £5. Some readers have misinterpreted the purpose as pleasure, but it is medicinal. We require a weekly antidote to the toxins released into the bookselling system by certain mainstream publishers. The virus mutates: A Shite History of Nearly Everything, Shite's Original Miscellany, Eats, Shites and Leaves, Do Ants Have Arseholes?

The Archive Bookstore at 83 Bell Street, a short hop from Marylebone Station, is a tonic in itself. Here are the bountiful outdoor barrows full of LPs, books and sheet music. Here is the aproned counterhand, polite and helpful, undaunted by the Sisyphean task of shifting cartons of books to permit access to shelves, only to obscure other shelves. There goes the proprietor down to the basement, from where he conjures Chopin variations on the piano with wooden keys.

If eager to improve your language skills, visit the Archive. Packed into excavated recesses on the way to the basement are books in foreign languages. Dig through one layer to uncover the New Testament in Danish; dig deeper for David Irving's study of Hitler in German; archaeological tenacity and a torch reveal Jane Austen's Sentido y sensibilidad. We were briefly tempted by Volume I of The Brothers Karamazov yoked together as a pair with Volume II of War and Peace.

Instead, we lighted on a genuine curiosity: Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction by Patricia Highsmith. Few, even among Highsmith's admirers, are aware of this enlightening book. It was published in 1983 by Poplar Press of South London. The advice is practical and down to earth. She prefers an opening sentence "in which something moves and gives action", and sure enough almost all her novels begin with movement:

"The train tore along with an angry, irregular rhythm." (Strangers on a Train)

"Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way." (The Talented Mr Ripley)

"It was jealousy that kept David from sleeping, drove him from a tousled bed to walk the streets." (This Sweet Sickness)

She wishes to suggest "a bottling up of force that will one day explode". The action is needed because "the reader does not want to be all at once plunged into a sea of complex facts". Her advice extends to writing in general: for example, that the last sentence of a chapter, a section, even a paragraph, can often be cut to the benefit of what has gone before.

The Archive charged us £3.50 for Highsmith's wisdom. We bought a stack of other books as well. The man in the apron kindly knocked a few pounds off the total.

J. C.

Seventy-seven Shakespeares

At present, there are no plans to run a review of Roland Emmerich's new film Anonymous in the TLS. Careful analysis of its constituent parts – chiefly, the premiss that Shakespeare didn't write his own plays, but farmed them out to a conveniently ingenious yet secretive aristocrat (Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, played in the film by Rhys Ifans) – suggests that there might be better things to do with the paper's arts pages than reviewing Anonymous.

Sorry about that. But . . .

if the idea underlying the film really interests you, and you're a TLS subscriber, you could do worse than searching the online archives for, say, Alan H. Nelson's entertaining review of a book by trained astronomer about Oxford ("a poet of no more than modest talent") being the real Shakespeare. Published a few years ago, the book happens to being with a foreword by one of the actors in Anonymous, Sir Derek Jacobi:

"Jacobi, biting the hand that feeds him, recommends [this book] on the grounds that the Shakespeare plays were written by an actor, and that Oxford was an actor. Perhaps he had in mind a different book, for Anderson makes neither claim. . . ."

Or you could try Charles Nicholl's more recent piece on Contested Will by James Shapiro, a scholar who is interested not so much in "what people think – which has been stated again and again in unambiguous terms – so much as why they think it". This would seem to be the interesting part of the anti-Shakespearean delusion, if indeed there is one: it's a direct consequence of the deification of Shakespeare.

Anti-Shakespeareans tend to believe, in Nelson's words, that "an author's life is reflected in his works" absolutely. Shakespeare wrote a play about a prince; he must therefore have been a prince. He wrote a play about a Scottish murderer. He must therefore have been a Scottish murderer. He knew a bit about life at the Elizabethan court and history and – stuff. Well, he must therefore . . . etc.

They are not alone in taking things literally, of course, as Shapiro argues; but they have proved to be curiously imaginative over the years in attempting to deny that the author of A Midsummer Night's Dream had, of all things, an imagination. And as Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells point out in Shakespeare Bites Back, a polemical essay published online for free (you can also hear more about the subject over here) to coincide with the general relase of Anonymous, literalism leads its adherents into a predicament: they can't all be right.

There is the Earl of Oxford (who died in 1604, most inconveniently for the plays he then continued to write, well into the following decade). But then there are therefore a further seventy-six individuals who, over the past century-and-a-half, have suffered nomination as the "real" author of Shakespeare's plays. Are they all Shakespeares now?

Seldom did these candidates have anything to do with the theatre (except for Christopher Marlowe, but then he went to university, which makes him fair game). But they do tend to be awfully well connected. It's the literary-biographical equivalent of the syndrome whereby a child becomes convinced that her real parents are royalty or millionaires.

Understandably, many Shakespeare scholars seem to prefer to stay as far away from this non-debate as possible. Edmondson and Wells argue, however, that because Anonymous "humourlessly" presents itself as history, as a dramatization of the truth, something needs to be said against it. Others will see in it "an amusing and mischieveous Blackadder-style romp". But Rhys Ifans can be awfully convincing, you know. Stephen Marche, writing in the New York Times, predicts that, after Anonymous, "undergraduates will be confidently asserting that Shakespeare wasn't Shakespeare for the next 10 years at least, and profs will have to waste countless hours explaining the obvious". Let's hope that he underestimates undergraduates' capacity for scepticism.

Not coincidentally, Shakespeare Bites Back names and shames the world's most notorious piece of anti-Shakespearean punctuation: the question mark after "1593" in the window that commemorates Marlowe in Westminster Abbey: this is as much to suggest that he didn't die in that year, as the coroner seemed to think, but survived being stabbed in the eye in order to write, well, such un-Marlovian works as The Merry Wives of Windsor and All's Well That Ends Well. Edmondson and Wells call on the Dean to get rid of the question mark (somehow).

Roland Emmerich, meanwhile, ought to be thinking of a sequel. Anyone for Anonymous 2: The mighty line? One "Shakespeare" film down, seventy-six more to go . . . .

October 24, 2011

Quiet Cocteau

I recently received as a gift a book called Quiet London by Siobhan Wall (2010), a compendium of places in which to escape the noise and din. Inspired, Wall says, by the French situationist Guy Debord, she directs the frazzled flaneur to the city's less-frequented museums, galleries, libraries and places of worship.

Which brings me, meanderingly, to the French poet, painter, playwright, novelist, designer and cineaste Jean Cocteau, hiding up a side street off Leicester Square. This particular enclave of the City of Westminster is, perhaps, the spiralling hell-hole par excellence from which Wall would deliver us, where tourists flock under the impression that it is the centre of the centre – the real London – which seems doubly cruel considering its denomination is so difficult for non-English speakers to pronounce. Here, they will find authentic Londonese deep-pan pizzas; Chinese restaurants exhibiting deeply tanned ducks; multiplex cinemas showing everything and anything at once (as long as its budget is big); and one cinema up a side street which plays The Sound of Music on loop.

But concealed up the same side street is the Church of Notre-Dame de France – blitzed in the 1940s and rebuilt in the mid-50s. And here, if only they knew to look, passers-by would find a mural painted by Jean Cocteau over the course of eight days in November 1959, when he was in London promoting his film Le Testament d'Orphee, the final part of an Orphic Trilogy, which includes The Blood of a Poet (1930) and Orphée (1950).

The media clamour around Cocteau then was such that scaffolding had to be erected around the entrance to the church to enable him to work in silence. He would arrive, so the story goes, at 10am every day, light a candle in the chapel, and could then be heard whispering to his figures as they took shape beneath his brush.

Spanning three walls, the mural depicts a crucifixion scene, with shapely Roman soldiers, their nipples erect, who would not be out of place in an advert for Jean Paul Gaultier; swooning women, their eyes cast down, weeping blood, or with their heads thrown back, irises straining towards the heavens.

Of Christ, only his frail legs and feet are shown, dripping blood onto a red rose positioned at the base of the Cross. Slightly off-centre and below the line of vision is Cocteau himself, a self-portrait in which the artist's ambivalence to Catholicism seems palpable: with his back to the Cross, his brow is furrowed and his left eyebrow raised. To his right, a game of dice plays on the odds. If his expression is one of scepticism, his lips are pursed and tightly sealed. These are light strokes on cool concrete from which no answers can issue, but there are echoes, nonetheless, of Cocteau's epitaph in the Chapelle Saint-Blaise-des-Simples in Milly-la-Forêt where he is buried: "Je reste avec vous".

Siobhan Wall's missive, put forth in her Introduction, was to discover locations in which "both time and space seemed suspended". Cocteau's mural in the Church of Notre-Dame de France, in London, just off Leicester Square, on a Sunday afternoon in October is just such a place. Cocteau himself remarked that as he was painting there, time seemed to stand still around him and, leaving the church once the project was complete, he reportedly said "I shall never forget that wide open heart of Notre Dame de France and the place you allowed me to take within it".

The prolific Powyses

As a postscript to my piece on the eccentric novelist T. F. Powys, I suppose I'd better acknowledge that this Powys, the one whose work I admire the most, isn't the only one among his many brothers and sisters, who grew up in the late nineteenth century but didn't come to any great literary prominence until the 1920s. Aficionados sometimes liken them to the Brontës, but that suggests only three or four writers in a single generation, whereas "TFP" had ten siblings in total, and most of them scribbled at one time or another:

There was John Cowper Powys (long-lived and prolific), Llewelyn Powys (whose African essays were republished last year), Philippa Powys (who struggled to achieve much in her day but has been more recently rediscovered), Littleton Powys (sometime headmaster of Sherborne School, whose memoir The Joy of It has to be mentioned if only as an excuse to mention the fine title of its sequel: Still the Joy of It . . .), Marian Powys (who wrote an authoritative book on lace-making), and A. R. Powys (who wrote on church architecture).

Of the others in this large family, one died young ("a delicate, talented girl, full of poetic fancies", according to Morine Krissdóttir's biography of "JCP"); two of the others painted. I am hopeful that the eleventh remaining Powys, Lucy, didn't do anything at all. But this is not to mention the extended family and the wide circle of friends and acquaintances . . . .

October 22, 2011

NB: Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 3

J.C., the author of the TLS's NB column, has made his third sally into London's secondhand bookshops for the purposes of his "Perambulatory Christmas Books" series – the aim each week being to find a neglected work or curiosity, for about £5, to "brandish as a clove of garlic" against the horror of mainstream Christmas fare. Here is the latest instalment:

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part III. On a previous tour of duty, we compared some secondhand bookshops with their neighbouring Oxfam rivals. In almost every case, the privately owned shop came off better. Oxfam Books in Marylebone, for example, cannot compare with the nearby Archive Bookstore, a glorious Dickensian jumble. On another occasion, we went to Gloucester Road, to survey Oxfam at No 46, and the Gloucester Road Bookshop further down. Two years on, the former has closed, while the latter is transformed into Slightly Foxed on Gloucester Road.

Like My Back Pages in Balham (NB, last week), Slightly Foxed deals in both new and used books. Unlike the Balham shop, where all is happily topsy-turvy, the Foxed stock is well regimented. Our weekly endeavour is to find a neglected work or curiosity by an established author for about £5, to brandish as a clove of garlic against the blood-draining horror of mainstream Christmas fare (Do Ants Have Arseholes?, My Shit Life So Far, etc). This proved tricky at Slightly Foxed, where anything languishing in a pile is strictly disciplined. Books stand to attention, spines rigid. Every browser knows that an ounce of chaos is worth a pound of order.

In spite of obstacles, we achieved our goal. Journal of a Husbandman by Ronald Duncan, published in 1944, is certainly curious. There was a time when Duncan was more famous than his near homonym, Robert, but no longer. In the 1950s alone, the TLS reviewed ten of his books of poetry and verse drama, most issued by Faber, like this one. In 1939, dissatisfied with literary life, disgusted by impending war, Duncan withdrew to the country and a life of pacifist self-sufficiency. "One-eighth of an acre of garden produces enough vegetables for a family of four for a year." A few commune types came too. When a neighbour, Mrs Yatter, offered to do housekeeping, Duncan took a stand. "I have told her explicitly. The washing of our own clothes is as important a part of our embryonic discipline as making our own bread."

It could have had charm. But when you read that one co-worker, Karl von Hothstein, is "a member of the Hitler Youth [who] regards Der Fuehrer with hero worship", the charm fades. Karl "dislikes the Jews" – this was August 1939 – but still gets to work on Duncan's farm. Another is a hardline Leninist. By spring, he had had a breakdown and Karl had been fired – not for Hitler worship, but for carrying on with Mrs Yatter. By 1942, the farm cottage had gone back to its "original inhabitants . . . rats, robins and starlings".

Duncan went on to help found the Royal Court Theatre in the 1950s and, unlikely as it sounds, write the script for the film Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), starring Marianne Faithfull. It is good news that a secondhand bookshop endures on Gloucester Road, but we'd enjoy the taunts of a few rats, robins and starlings peeping through the stacks.

October 21, 2011

Robert Hughes: a reply?

Should writers reply to reviewers? I remember when mostly they did not. I now edit a paper where often they do.

I am sympathetic to both positions.

But people have started to ask me whether the Australian critic and historian, Robert Hughes, has replied anywhere to my remarks earlier this year about his 'history' of Rome.

I cannot say. I don't know.

I am old enough not to assume that just because there is said to be nothing on line that nothing therefore exists.

Perhaps Mr Hughes has explained himself, even apologised to the purchasers of his peculiarly careless tome.

Perhaps he considers himself too grand to do so. I do not blame him for that either.

I first raised the oddities of Hughes's Rome in a post on this site - and then summed them up in the Australian Book Review.

For those who missed that piece - or are still wondering whether author or publisher has a reply - I am copying it below.

This is purely for information to those who have asked. If no explanation has yet come, then probably it will not.

Fine.

"There are two sorts of carelessness that a reviewer of history books will regularly see. The first is a minor marring of virtue, a small blot on a show of swashbuckling confidence and command over grand themes, a lack of care for what lesser men may think, arrogance even; we often call this being carefree rather than careless. The critic can correct and admire and move on.

The second sort of carelessness is unsettling,almost a vice, a show of unconcern and shallow understanding, an arrogance of a different kind, a lack of care of any kind. In his 500-page account of the history of Rome, Robert Hughes is doubly, gloriously and disgracefully careless.

Most history books contain errors; but Hughes's account of some 3,000 years from the foundation of Rome to Fascism and Fellini has anextraordinary number. Some, particularly in the later part of the book,are pure errors of virtue. Unless a critic finds pleasure in carping (a satisfaction that can be concealed sometimes by the claim that one is helping the author for his second edition) it is of small moment to note that to describe George Gissing's 'By The Ionian Sea' as a'long-disregarded novel' is to disregard the fact it is not a novel atall. Fellini's film, La Dolce Vita, whose photographer, Paparazzo, took his name from Gissing's travelogue and handed it on to celebrity snappers across the world, gets such exuberant attention in Rome that it hardly matters that Gissing's work has been 'disregarded' (ie unread) by Hughes too. This author oozes eloquent passion for Bernini and Caravaggio and if critics find the odd error in all of that, too bad.

In the first half of the book, however, the carelessness is decisively different. Hughes begins his history long before the Renaissance sculptors, papal architects and fashionable film-makers that he evokes so fiercely. To pick a passage almost at random, on the last page of the second chapter Hughes writes about the death of Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, and how 'smoothly' went the transition of power to his successor, described as 'Livia's eldest son by him, Tiberius'.

If Tiberius had actually been 'Livia's son by him, her son by her second husband Augustus, the succession might well have gone smoothly (or not);but he was not Livia's son by Augustus at all. Tiberius was Livia's sonby her first husband Tiberius Claudius Nero, a rather remarkable Roman in himself.

Augustus founded a great empire. Tiberus Claudius Nero lost his wife to this most ambitious and successful man of his age but ended up siring a vast dynasty of imperial potentates, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero. An easy and forgivable mistake? Well, quite easy and forgivable, I suppose, unless you are being paid to write a history of Rome; you would also need to have forgotten Robert Graves's I Claudius and all the soap-opera versions.

The achievement of Livia's first husband was the sort that has often very much mattered to Romans. Augustus himself sired only one child, a daughter, a matter also of note to anyone for whom theancient history of Rome has been a genuine care.

Two pages further on Hughes tells of another death, that of the African king, Jugurtha, 'of starvation in 105 CE' - which would be a fine addition to a section on the Emperor Caligula's prison policy if Jugurtha had not died more than 200 years before. Fine again, the author or publisher might say. That is the old BC/AD, BCE/CE confusion, easilydone; so easily that it is done in the next line too. Vercingetorix, 'Caesar's chief enemy in Gaul', is executed in '46 CE', ninety years after Caesar himself was killed.

Does Hughes care about gladiatorial shows? Most historians of ancient Rome do, some of them too much. But it is unsettling to read a declaration that 'a succession of autocrats, starting with Augustus himself and continuing onwards through Pompey and Julius Caesar, treated these games as the greatest imperial show of all'. Onwards? It wasAugustus who succeeded Julius Caesar and Pompey. Continuing backwardsperhaps? The beginning and end of Augustus's reign are twin hinges on which Roman histories hang. Here there seems to be no care for either.Hughes posits Nero's architects planning the Colosseum, the most famous Roman building of all, famously built to obliterate Nero's massive Golden House palace and other unpleasant memories of his reign. If any of his architects were planning this edifice before his death, they were brave men indeed.

On the same page Hughes discusses the gladiator emperor, Commodus, not an obscure figure today following his depiction in the film, Gladiator. In 138 CE, Hughes writes, the deranged, dissolute Commodus was the 'son and successor' of the Emperor Hadrian. No, he was not. Commodus's father, as shown in the film and in all history books, was the philosopher emperor, Marcus Aurelius, whom Commodus succeeded in 180 CE,some forty years later.

Hadrian's own successor was Antoninus Pius whom Hughes bizarrely describes as 'the Christian Antoninus Pius'; the identity of the first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great in the early fourth century, is hardly a trivial matter for a writer of a book called Rome. Antoninus Pius, though modest in his Christian persecutions by the standards of some, was properly deified after his death into the pagan pantheon.

Does any of this matter? Each error individually maybe does not. Maybe they will all be corrected, the earlier copies pulped. Or to confuse Pompey with his father will be judged merely unhelpful; to write the name of Miltiades, the Athenian aristocrat, instead of Mithradates, a Roman enemy from 400 years later, only a slip of the aural memory.

Hughes quotes 'the famous Cleopatra epode' when it is the ode which urges us 'nunc est bibendum' and the epode is rarely read at all. Who will care? Few perhaps. But when all is taken together, whatever corrections are made, surely the buyers ofthis book have been taken for a ride.

The emperor Marcus Aurelius, for example, is an important figure fo Hughes as he is for most historians, not one of those minor characters about whose fatherhood a writer can make a virtuous mistake. His equestrian statue in Rome is one of the city's great surviving artworks from its ancient past and for Hughes was 'the most decisive and revelatory' sight when he first visited the city in 1959.

Hughes cares about art, and this piece of art in particular; in the epilogue to the book he rails against the modern 'vandalism' that has removed the bronze rider to a ramp in the Capitoline Museum 'slanting meaninglessly upwards in a way that Michelangelo would never have countenanced. But a historian has surely to care enough about the man too, enough to avoid awarding his son, even his most disappointing son, to someone else.

A challenge for any historian of early Rome is to help the reader discern what might be true and what is certainly false, what was legendary, what is historical, why the traditional stories were told, retold and adapted. That task is important not merely for the antiquarian pedant but because in the oldest history some of the problems of all history are most starkly shown.

This was not territory that Hughes was obliged to enter. Many historians of Rome have wisely avoided the questions of Romulus and Remus and the flight of Aeneas from Troy.

The city's early history is a collective memory created by poets and propagandists of the Augustan age, constructed out of myths passed through many memories over many centuries. Therefore to cite 'the great historian Livy' for the account of how Aeneas's descendants were suckled by a she-wolf is a nonsense even as a careless aside. Livy knew almost nothing about the Rome of eight hundred years before his birth - and what few facts that he did know he did not allow to get in the way of a good story.

By contrast what Hughes describes as the 'legendary date' ofthe fall of Troy was, in fact, the first recognisably scientific date,offered in the second century BCE and quite close to what we now think is the truth.

The best Roman writers themselves - Cicero in the forefront - had a sophisticated understanding of memory, myth and history. So did many of the hundreds of historians who have followed. It is no tribute to them - or to the city whose story Hughes writes - to reduce that thought barely to the level of a bad guide book, the sort used and sold by those 'artistic illiterates' that in his epilogue, boldly and wholly without irony, he judges now 'most Italians' to be.

Georgiana the witch (and other eighteenth-century actresses)

Here's how visitors to the National Portrait Gallery can see the witches from Macbeth this autumn: as portrayed in chalk and gouache by Daniel Gardner in 1775, and "played" by a trio of friends, the Duchess of Devonshire (or just "Georgiana" to readers of Amanda Foreman's biography), Viscountess Melbourne and the sculptor Anne Seymour Damer.

The online catalogue notes that there may be political allegory lurking here – although it's tempting to think that the claim that if there's no direct parallel for the work's "composition" elsewhere in Gardner's oeuvre, there is at least a male counterpart – three political animals caught in the middle of their plotting – by Gardner elsewhere in the NPG itself. All they need is a cauldron.

"Georgiana the witch" is one of two significant novelties in an exhibition that's just opened at the NPG, The First Actresses . . .

The other one is a century older, by Simon Verelst, and depicts Nell Gwyn in a state of undress (it's reproduced in this week's TLS).

There are some familiar images among the other fifty, including a copy of Sir Joshua Reynolds's "Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse". Note the face to Siddons's left, based on the artist himself:

(The much-reworked original is in California, where it sits majestically, and in good artistic company at the Huntington Art Gallery; is it wrong to prefer this one, not in the exhibition but elsewhere in the gallery?)

Perhaps most interesting from a theatrical point of view are the scenes inspired by theatrical productions of the eighteenth century, which include a Hamlet of 1777 knocking over his chair when he sees the ghost of his father for a second time – a decades-old, if not century-old, piece of business.

There's also Thomas Gainsborough's portrait of the dancer Giovanna Bacelli, the comic actor Henry Angelo in drag, "Frances Abington as Miss Prue" (another classic piece of work by Reynolds, but fading fast), a few satirical swipes at all this vanity and self-promotion courtesy of James Gillray, and the more famous one of Nell Gwyn (by Verelst again), in which she almost succeeds in staying in her clothes. Almost but not quite. . . .

October 20, 2011

Private Eye at the V&A (and in the TLS)

"Every time you go through the pile there might be someone new who's good", says Ian Hislop of his search through the hundreds of cartoons submitted to Private Eye each fortnight. "I always think it's one of the best bits of being editor". Private Eye: The first 50 years, which opened at the V&A on Tuesday, celebrates all those cartoons – "whether savage or simply funny, with or without words" – that have made it on to the page since 1961. The many cartoonists represented include such masters as Willie Rushton, Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe.

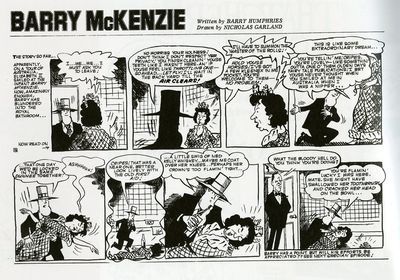

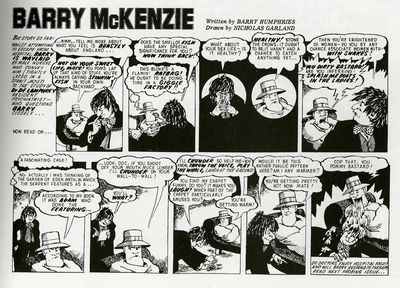

In introducing the display, Hislop said that it was important to indulge cartoonists' little obsessions. There are good strips that "come from nowhere and are often about nothing". All cartoonists have their idiosyncratic methods. He referred to "Barry McKenzie" (c.1965–1974), written by Barry Humphries and illustrated by Nicholas Garland, which was suggested by Peter Cook as "an Australian Candide" and became the Eye's first really popular feature. Much of the Australian slang, Hislop told us, wasn't Australian at all: Humphries had made it up.

For more about the idiom of "Barry McKenzie", visitors to the exhibition need look no further than an article, reproduced in part below, entitled "The Living Language", written by Humphries himself and published in the TLS of September 16, 1965.

"From the time . . . we had thought of presenting the adventures of an Australian Innocent Abroad who spoke in the 'fair dinkum sport' jargon which would be most familiar and comprehensible to English readers. However, as the idea grew and the comic strip became popular, Kenneth Tynan, Alan Sillitoe and Bernard Levin numbering among its more distinguished fans, the stereotyped Australianisms and the obsolete Edwardian slang tended to disappear, and the ellipses and euphemisms of true Australian speech took over. For all that, Barry McKenzie is a pastiche figure. His vocabulary is borrowed from a diversity of national types, and words like 'cobber' and 'bonzer' still intrude as a sop to Pommy readers, though such words are seldom, if ever, used in present-day Australia. The character has been theatricalized and heightened in order that he may be accommodated within the marionette world of the strip cartoon, so that although the shattered syntax is most painstakingly recorded, the slang and the euphemisms which it encases are lifted from a wide cross-section of Australian society. We have attempted to preserve the rhythm, colour and texture of modern Australian speech without fixing the character of Barry McKenzie too firmly in an identifiable class. It is sufficient that he is now recognizable to English readers . . .as a familiar expatriate figure; someone they know. Only the baggy trousers and the wide brimmed hat anchor him to an image of the 'stage' Australian, or the Boy from the Bush. Needless to say, if such a figure walked down Collins Street, Melbourne, now, not a few heads would turn.

Barry McKenzie is a puritan eccentric, and among his many idiosyncrasies a desire to pass water at the most inopportune moments has become increasingly manifest. In nearly every episode Barry feels the Call of Nature which gives the strip a superficial resemblance to the paintings of Teniers and his school. McKenzie employs a number of colourful and expressive Australianisms to describe this prosaic function; straining the potatoes, having a snakes (rhyming slang), flogging the lizard, splashing the boots, writing his name on the lawn, pointing Percy at the porcelain, shaking hands with the wife's best friend . . . .

His enormous consumption of gelid Australian beer on an empty stomach has not infrequently led to disaster, and his favourite word to describe the act of involuntary regurgitation is the verb to chunder. This word is not in popular currency in Australia, but the writer recalls that ten years ago it was common in Victoria's more expensive public schools. It is now used by the Surfies, a repellent breed of sun-bronzed hedonists who actually hold chundering contests on the famed beaches of the Commonwealth. I understand, by the way, that the word derives from a nautical expression 'watch under', an ominous courtesy shouted from the upper decks for the protection of those below . . . ."

Private Eye: The first 50 years

October 18, 2011–January 8, 2012

Studio Gallery

Rooms 17a and 18a

Free admission

Cartoons taken from Private Eye – The first 50 years: An A–Z by Adam Macqueen (312pp. Private Eye Productions. £25. 978 1 901784 56 5)

October 18, 2011

The TLS on the Man Booker shortlist

After the accusations of dumbing down and the announcement of an "uncompromising" rival to the Man Booker Prize, which novel is going to win tonight?

Ladbrokes will tell you that while The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes is the "hot favourite", paradoxically, "The favourites have had a tough time historically and we wouldn't be surprised to see a shock result". So much for being the "favourite".

The TLS has reviewed all six shortlisted novels over the past ten months. Here's what we made of them:

Reviewing Snowdrops in January, Daniel Jeffreys enjoyed A. D. Miller's "dense descriptions of different types of sleet and snow set the scene for an amoral, emotionally frozen city which has defrosted too quickly from Communism".

Judith Flanders greatly enjoyed Jamrach's Menagerie by Carol Birch in February, although "the author's love of metaphor runs out of control": "the gore-flecked description of the sailors carving up their massive catch is a masterpiece, the research so well integrated that the material comes across as lived events rather than history".

In April, Douglas Field declared Pigeon English to be "reminiscent of Hanif Kureishi's early work" in its "observations on . . . unfamiliar London life" that are "full of satirical charm" – but the novel's "comic set pieces undercut the effect of the dark subject matter" (inspired by "the stabbing of ten-year-old Damilola Taylor, the Nigerian schoolboy found dying on a concrete stairwell on a Peckham council estate in 2000"). He was also put off by the way the book was marketed:

"Kelman deals sensitively with the subject matter of teenage violence, and it is a shame that the publishers have been so keen to flirt with worthiness, clearly marketing the novel at book clubs and A-level students. Do we really need fourteen discussion points after we have read the novel? . . . Kelman has written an accomplished first novel but its promotion dilutes, rather than reinforces, the impact of its timely subject."

Chris Cox's review of The Sisters Brothers by Patrick deWitt appeared in June to be a "powerfully realized work of narrative fiction", but that "its reference points are more cinematic rather than literary", the novel working "artfully within its formal boundaries to explore the nature of brotherhood, work, love, greed, loneliness and personal renewal".

In August, Lidija Haas observed that The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes is poised "between a straightforward story and a novel of ideas" – "Barnes has it both ways, just as he often contrives to be so English and so French at once" – and that its style is "more restrained, less showy than it has sometimes been in the past, the wit is quieter, more sparingly used . . . . the main pleasures of reading The Sense of an Ending are the solid, traditional ones of story and character".

Finally, earlier this month, Charlotte Ryland reviewed Half Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan, and found it "captivating":

"The Nazi era continues to fascinate British and American readers, so if the Booker Prize shortlist has become more international this year, it is perhaps not surprising that one of the shortlisted novels has Third Reich Berlin as its setting. But Half Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan excites precisely because it provides such a fresh view on this well-worn setting."

In other words: they're all hot favourites to us. . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers