Peter Stothard's Blog, page 77

January 6, 2012

Sherlock: 'Think! It's the new sexy'

As Toby Lichtig puts it in this week's TLS, "Midwinter is a potent time for fans of Sherlock Holmes. . . . Only Charles Dickens has greater seasonal appeal and this winter, despite a bicentenary, even he can barely compete".

Lichtig reviews a host of fiction, biography and essay based on Holmes or his creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He says of Anthony Horowitz's The House of Silk, the first "official" Sherlock Holmes book since 1930: "Like the best Holmes stories, it treads the line, in both narrative and language, between cliché and creativity".

The same might be said of the second series of the BBC's Sherlock, written by Steven Moffat. Cliché's such as Holmes's deer-stalker are certainly put to creative use. There are cunning plot lines, cool editing, that sort of thing.

Episode one, "A Scandal in Belgravia" is based on the Conan Doyle short story "A Scandal in Bohemia", the one in which Sherlock meets "the woman", Irene Adler. In the BBC's version, Adler, wearing nothing but Sherlock's overcoat, declares "Brainy is the new sexy". (The show had nearly 9 million viewers - more than a Downton Abbey Christmas special, but not as many as Eastenders). Sherlock is confounded.

In the original story, Watson concludes that "The best plans of Mr. Sherlock Holmes were beaten by a woman's wit". Whether the same can be said by the end of the Beeb's show has been called into question in the Guardian, where Jane Clare Jones found the whole thing sexist. "Granted, [Moffat] allowed [Adler] to keep her smarts. But, at the same time, her acumen and agency were undermined every which way." In Moffat's rewrite, Adler no longer beats Holmes, but must be rescued by him.

Another problem was thrown up by "a full 25 minutes" of pre-watershed nudity (Adler's – pointed out in the Mail), and a grammatical error, (Sherlock's – pointed out in the Guardian) "Did you know there were other people after her, Mycroft? Before you sent John and I in there?"

Nit-picking? It's in the spirit of Sherlock. And until the Dickens bicentenary gets into its full stride, it's the spirit of the day, or – as Moffat might have it – the new sexy.

January 3, 2012

Twelve perambulations and one professor

Happy new year and all that – and today, O inhabitants of Planet Tolkien, happy anniversary – the toast is: "The Professor!"

In other business, meanwhile . . . back in October, reports of useful expeditions to the depths of London's bookshops began appearing on the back-page of the TLS. Here's the summing up, from the final issue of 2011, December 23 & 30 (a double issue, please note).

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 12

By J. C.

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part XII. Introducing our first-ever tour in 2007, we said that each book written about will have been found "at one of London's secondhand bookshops, which lazy reports deem an ailing species". Four years on, during which the abundance of gadgetry has increased, there are few signs of greater frailty. The best shops – Any Amount of Books, the Archive Bookstore, Walden Books – are still here. Keith Fawkes of Hampstead endures, through a pestiferous bric-à-brac stall which comandeers half its space. The outdoor barrows at Peter Ellis, Cecil Court, glisten with treasure. We paid £2 there for a lovely first edition of So Late into the Night by Sydney Goodsir Smith (1952).

In my saul's a Universe

Whaur ramp the restless deid,

Othello reives my thrawan hert

And Lear raves in my heid.

Two shops new to us were My Back Pages in Balham and LXV Books in Bethnal Green. The Gloucester Road Bookshop closed one night, and Slightly Foxed on Gloucester Road opened next morning – rather too well-ordered for our tastes (nothing discombobulates the Perambulator more), but it is there. Our office neighbourhood hosts three shops: Skoob, Judd and Collinge and Clark.

The original impulse was to offer readers an alternative to the Christmas gift books offered by certain publishers, such as Do Ants Have Arseholes? And 101 other bloody ridiculous questions. It never occurred to us that one day we might read it. But in the course of a rainy perambulation, on the shelf of an East End Buddhist bookshop, we found it! And do you know what . . . . Well, you've guessed. It's rather good. We may now ask, and answer, questions such as "Are there any undiscovered colours?", "What was the best thing before sliced bread?", "Is laughter the best medicine?". There is even philosophy, of the kind we've never been good at: "Will your answer to this question be no?" Let's risk a seasonal Yes. Next Christmas, we might attempt this kind of thing ourselves and submit it to the team in the basement labyrinth for publication. Where do you find good books for round about a fiver?

December 30, 2011

Double issues

The TLS goes to press on Tuesday for publication on Friday. Every Tuesday, that is, except for two Tuesdays per year. In the last week of August, and the last week of December the TLS staff take a "reading week", an office half term. To compensate, there is always a double issue the week before "halfers": the summer double issue and in this case, the Christmas double issue.

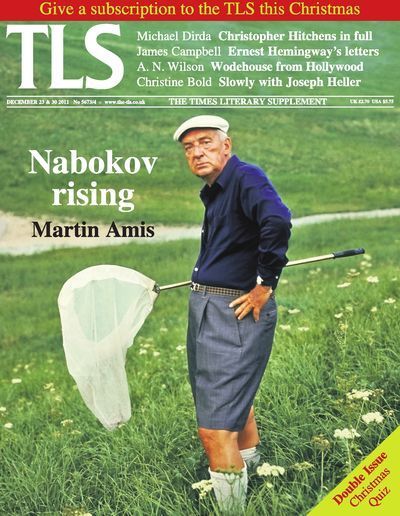

The current Christmas double issue, dated December 23 & 30, includes Martin Amis on Nabokov, James Campbell on the letters of Ernest Hemingway, A. N. Wilson on the letters of P. G. Wodehouse; pieces on Christopher Hitchens and Steve Jobs; reviews of Swallows and Amazons at the Vaudeville Theatre, the film Hugo and the film Margaret; Joseph Heller, Georges Simenon, Harold Bloom, Alice Oswald. The list goes on. And then there's the Christmas quiz.

Many longstanding subscribers will know off by heart not to expect a new issue today, December 30. Some will understandably get caught out, and might call in, to say they are missing a TLS. The week before was a double issue, we explain, everyone needs a week off.

But it was not always thus.

In its first year of publication, 1902, the 49th issue of the TLS appeared on Friday, December 19th; the 50th on Friday, December 26, and then once more on January 2, 1903. It seems that the paper's staff scarcely drew breath over Christmas.

Issue number 50 contained reviews of "Mallet du Pan and the French Revolution" ("This is an excellent book"). A review of Rural England: Being an account of agricultural and social researches carried out in the years 1901 and 1902. A piece from a correspondent that began: "The enterprise of the Clarendon Press in supplying a really adequate facsimile of the 1623 Folio of Shakespeare's Plays has met with a success as gratifying as it was in the first place unexpected." In total twelve books were reviewed alongside essays on Nathaniel Hawthorne and a letter on the relationship between banker, publisher and copyright.

Issues number 5673 and 5674 may come bound together, but they contain reviews of 53 books, three plays, two films, an exhibition, a ballet, eight volumes of the selected Kleine Schriften, three poems, commentary on the ancient Jewish historian Josephus, Freelance, Then and Now, JC, and of course (not a partridge in a … ), but the Christmas quiz.

December 22, 2011

The unseen Jane Austen?

© Paula Byrne

Is this Jane Austen? On Boxing Day at 9pm, BBC2 broadcasts Jane Austen: The unseen portrait?, in which the biographer and Austen scholar Paula Byrne suggests, with the support of art historians and costume experts, that it is.

Other authorities on Austen have suggested that this could be an "imaginary portrait" or a "memorial portrait" of the novelist, but Byrne can counter such objections:

"Despite asking numerous experts, I have not found any examples of early nineteenth-century 'imaginary portraits' of contemporary writers. There are indeed 'memorial portraits' (Joseph Severn of Keats, many images of celebrities such as Byron and Nelson), but they are always derived, directly or indirectly, from life portraits. If this is a 'memorial portrait', where is the life portrait from which it is derived? Rather than supposing that two portraits of Austen have been out of view for nearly 200 years, I prefer, till counter-evidence comes forward, to accept the consensus of the art historians and costume experts in my film where the portrait is dated to 1814 or 1815, when Austen was at the height of her powers."

As it happens, this claim comes at a moment when Austen has made the news for other reasons, whether it's the widening of access to Austen family archives, archaeological investigations in Steventon, or the announcement that Joanna Trollope is to essay a "contemporary version" of Sense and Sensibility.

But if Byrne's "unseen" Austen portrait is authentic – and you'll have to wait until after Christmas to hear the full range of evidence and speculation – then it also provides an interesting sequel to the saga of the much-disputed Rice Portrait, which once graced the cover of the TLS and inspired a debate that, I hope, we'll be able to publish online as a TLS Argument in the new year:

The Rice Portrait depicts a young woman who, in Claudia L. Johnson's words, seems "spirited, ironic and disarmingly self-confident, altogether capable of sitting in her corner of the common parlour and laughing at the world, as Virginia Woolf imagined on reading Love and Freindship". It's been suggested that the painting shows Austen around the age of fourteen – ie, circa 1789. By contrast, Byrne's Austen, a couple of decades later, has the prominent family nose, a pen in her hand, and a church very respectably visible in the background. The cat on the table politely declines to disturb the author as she drafts a chapter of Emma. Perhaps the one in which Harriet Smith sits for her portrait.

Of course, it is unlikely that everybody will immediately be persuaded of the portrait's authenticity after seeing Jane Austen: The unseen portrait?, since, as Johnson suggested more than a decade ago, the image of such a "national treasure" inevitably seems to elicit responses derived from deep-seated cultural sensitivities (cf. representations of that other elusive scribbler, William Shakespeare). In Austen's case, there is the familiar representation of her, in a watercolour by her sister Cassandra, that Byrne has dismissed as "very Victorian, sentimentalised and saccharine".

Take that, orthodoxy! (And let battle commence . . . .)

December 20, 2011

Babies from Cambridge

By PETER STOTHARD

The cover of the latest Cambridge Literary Review (not illustrated here) shows a baby in a glass box.

The butterfly mobiles and bedroom pictures suggest that she has been there for longer than for post-natal intensive care.

Peridot is the daughter of a professor from Cambridge, Massachusetts whose early concern for 'perfect control of her environment' creates a woman both saucy and sexless.

Or so she is at the beginning of Donald Barthelme's uncollected story, 'The Ontological Basis of Two', originally published under a pseudonym in 1963 for the mens' literary magazine Cavalier (a 1966 issue illustrated above).

Later Peridot is freed — to the pleasure of the narrator and one of many post-modern pleasures in CLR 5, edited by Boris Jardine and Lydia Wilson, which also includes a fine essay by David Hendy on another forgotten magazine, Wireless World, and some 'intoxicating' techno-fiction of fifty years before.

December 19, 2011

Perambulatory Christmas Books, part 11

JC

Perambulatory Christmas Books, 5th series, part XI: Our purpose has been to stave off Christmas gift-book blues by touring the capital's secondhand bookshops, in search of a neglected work by an established author, for about £5. We do not seek collectibles or firsts (although each has come our way). All our books are bought to be read.

The best used bookshop in London, from our lowly perspective, is Any Amount of Books in Charing Cross Road. It was there, five years ago, that we found in the outdoor barrows Edmund Blunden's The Face of England (1932), priced £1, and read the opening paragraph. No one could write like that now, we thought; the tune has been lost. We asked ourselves why, and with that the good ship Perambulation was launched.

Our most recent purchase at Any Amount was that unusual thing, a novel by George Gissing which is neither New Grub Street nor The Odd Women. Thyrza was published in three volumes in 1887. It is a romantic story with a tragic ending – damn you, Gissing – but we recommend it highly. In Chapter IV, poor but beautiful Thyrza sings in the Prince Albert pub down the Lambeth Walk. The stroll to the pub shows the author doing one of the things he does better than almost any English novelist, painting street scenes:

"Everywhere was laughter and interchange of good-fellowship. Women sauntered the length of the street for the pleasure of picking out the best and cheapest bundle of rhubarb . . . . From stalls where whelks were sold rose the pungency of vinegar; above all was distinguishable the acrid exhalation from the shops where fried fish and potatoes hissed in boiling grease . . . to be eaten on the spot, or taken away wrapped in newspaper".

It's sing-song night at the Albert – "a seedy youth at the piano was equal to any demand for accompaniment" – and our heroine is pressed to do a turn. "At the end she was singing her best – better than she had ever sung at home, better than she thought she could sing. The applause that followed was tumultuous. By this time much beer had been consumed."

The asking price for a 1927 Nash & Grayson hardback was £8, more than our limit. As we had a few supplementary purchases, the kind gentleman at Any Amount knocked a few quid off the total.

December 16, 2011

Christopher Hitchens in pictures

When our friends are dying, we know what we think we will remember of them.

When our friends are dying, we know what we think we will remember of them.

I had meant to have a lengthy obituary of Christopher Hitchens ready here to post when the thunderously advancing news of his death finally arrived. And, if I had done so, it would have contained many of the accolades that are crowding down today.

It might have also offered items from what an anthologising publisher once called 'The Quotable Hitchens'. Something on Kissinger, 'that rare and foul beast', or Princess Diana, 'like a dog being washed', or himself. 'I am, hope, never offensive by accident'.

Or perhaps the passage from September 2010 where he conceded that 'more once in my time have I woken up feeling like death' but that 'nothing prepared me for the early morning last June when I came to consciousness feeling as if I were actually shackled to my own corpse'.

But the bits and pieces, the brightly earned words of praise, don't quite do it this morning.

There are random pictures that do more:

* the first evening that I ever saw him, in 1970 at the Oxford Union when he led the shouting of 'murderer' and the hanging of a noose in the face of a Labour Foreign Secretary deemed over fond of the war in Vietnam.

* the day at the White House when he he quoted from what is the very little surviving of his poetry.

I Am the King of China,

I'm A Patron of the Prize-Ring.

And Every Time My Man's On Top

I Can Feel My Boxer Rising.

* the afternoon in a tent when he explained how the Boxer poem, composed to strict Oxford rules of versification, and the Vietnam War, fought at the same time to laxer rules, were nonetheless connected — via George Steiner and a rhyme sequence that does not seem appropriate to quote today. Readers of Hitch 22 can find it for themselves.

* the New Year in Palm Springs when Gerald Ford died and Saddam Hussein was hanged, when it seemed easier and more pleasant to sit together in a bar and deplore the faraway cell-phone footage, but somehow more necessary to drive to the airport and see Airforce One and a dead president's coffin for ourselves.

Well, it was more necessary for him. From Bosnia to Belfast to Baghdad (he had an alphabet of places scarred by religious bigots and those were just the Bs) he never missed a chance to get close. The rest of us went for the ride. There was a misunderstanding about cars and car parks. It was still good to have gone.

* the night in Hay on Wye when we sat together before what seemed to me a stadium of his admirers, with me tasked with ensuring that the talk was about his life, about his new autobiography, and not about god, Clinton, Iraq or Mother Theresa. He played his greatest hits anyway. He was a rock star writer and he never disappointed, certainly not on the last show he did here before the news of cancer came.

* the nights with him and Carol and Laura Antonia in Washington DC, the party when we first arrived in George Bush Senior's time, the party when we left, the warmth and depth of hospitality over so long, the love of his friends, the anxiety of friends and the admiration of millions in the months now over. Those pictures are the sharpest today of all.

December 15, 2011

Christmas without the humbug

BY DAVID HORSPOOL

Who is our most Christmassy writer? Everyone knows the answer to that one, especially in this year-before-the-anniversary year: yes, Dickens, again, whose Christmas Carol was merely the best known and most successful of several Christmas stories. You will be relieved to learn that this is not yet another Dickens blog, or even a blog about having had enough (already) of Charles Dickens. No, I would like to offer instead an alternative Christmas literary champion. The thought arose when I attended a rousing evening of prose, poem and song at St Mary's Old Church in Stoke Newington, North London last Sunday, at which an assortment of reasonably familiar (but not so familiar I remember their names) performers gave us readings in between perfectly-pitched a cappella renditions of carols and Christmas songs from all over the world by a choir a dozen strong, to whom our hostess, Selina Cadell, referred, gratefully, only as "those guys" (I have since discovered that they are known to some as the Occasional Choir). Considering that it was all part of a fundraising drive for an arts centre to be based at the church , a project that could hardly look more alien to the Victorian conception of what churches are for, this was an enjoyably old-fashioned type of evening, one in which it was hard to believe that the gale rattling the seventeenth-century window-frames was blowing across inner-city Hackney rather than wilder country heaths. There was no printed programme -- "too much faff, frankly", our MC explained -- but the readings I can reliably source came from Dickens (of course), from Thomas Hood, Hilaire Belloc, John Betjeman and Harold Nicolson, among others.

One writer's influence, however, both direct and indirect, was felt above all: Thomas Hardy. As you might expect, we had a reading from "The Oxen", with its extraordinary image of the beasts kneeling before the manger. Hardy manages to avoid Christmas schmaltz by painting the picture at one remove. The poet has not seen the remarkable sight, he has merely heard about it, and wants to believe it: "We pictured the meek mild creatures where / They dwelt in their strawy pen, / Nor did it occur to one of us there / To doubt they were kneeling then." The last line of the poem "Hoping it might be so", sums up with perfect economy the well-disposed doubter's feelings about faith and the festive season. Kit Wright used it as the title of a very much darker poem, which wishes that "There must be a place where the whole of it all comes right" in a world populated by murderers and rapists. Hardy's world has plenty of room for pain, of course, but his Dorset was brought to Stoke Newington in its more cheerful form, echoed by contemporary poets such as Catherine Simmonds, whose poem "The Stour at Hammoon" we heard, recalling the listless cattle and quiet riverbank of a Dorset summer (and recalling for me the tiny hamlet of Hammoon, where, as it happens, I got married ten years ago). There was also the very Hardyesque story of the church musicians whose home-brewed attempts to keep warm during the sermon lead inevitably to disaster. If it didn't actually come from Under a Greenwood Tree (no programme, you see), it was certainly in the spirit of that novel, which begins on a snowy Christmas Eve. The Hardy effect was still working for me as I strode home across sodium-lit pavements, imagining the rather more intrepid walks of the poet, who thought nothing of covering miles on foot to hear a decent sermon. Dorset had come to London, and Christmas had been rescued from the monopoly of London's most famous literary son.

December 14, 2011

Life after The Hare with Amber Eyes

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

Edmund de Waal's book The Hare with Amber Eyes traced the history of his Jewish diasporic family through its collection of Japanese netsuke carvings, acquired in the 1870s by the wealthy art collector and historian Charles Ephrussi. When the book was published eighteen months ago, de Waal thought that his work was over, that he could go back to being a ceramicist. In fact it wasn't, and he couldn't. The main problem, as he would probably term it, was the scale of his success: there were glowing reviews and prize nominations, and the book entered the bestseller lists. The publicity tour, it became clear, was going to be a long one.

At an Economist Books of the Year event at the Southbank on Friday, de Waal told us in detail about the unexpected difficulties such success brought with it. First of all, he had to talk about the book. He didn't want to read from it ("The number of times I've fallen asleep when listening to people I respect read from their own work . . ."), so he had to find a new language in which to reinvigorate it. Then there were the interviews: in New York Public Library the questioning was adversarial; in Paris the conversation – a short one – began "So, you write about Proust . . .". De Waal also had to reconcile himself to different publishers' tastes and marketing strategies: the American paperback edition has photographs in the "obligatory sepia" on the cover, and the hardback a subtitle of the "kitchen sink" school ("A family's century of art and loss"). The book has just come out in Brazil packaged in a velvet envelope.

It's all wonderful really, de Waal conceded, but one thing he continues to find difficult – a responsibility – is the correspondence. He has received thousands of letters from people all over the world, many of them intimate letters about what it is to be a refugee, or to be a descendant of refugees and not know where you come from. "I had no briefing", he said. "What do you do?" He now has a system: "When they come in they are sorted by age. If you are in your nineties you are written back to immediately".

When de Waal did return to his studio – "I'm a potter who has written things", he reminded us – he found that his years of research fed into his art. The book had been a sort of hymn to tactility, he told us, but the pain of discovering his family's traumatic history made him want to stand back. His artwork "Word for Word" initially consisted of vessels behind clear glass; as such it was reminiscent of the vitrine the netsuke were kept in before they were smuggled out of Vienna in 1938, and therefore "too obvious, too raw", so he made another case to go alongside it, this one with clouded glass. "Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror" was a meditation on the lacunae you come up against during research – the lost records, the pages torn out. In "Myself Behind Myself", another work in which vessels are partly obscured, de Waal tried to find "a way of protecting something". Other pieces explore "hidden things that have some kind of life".

A German edition of The Hare with Amber Eyes came out in August, and de Waal accepted an invitation to go to Vienna. He was worried about it, he said, but when he got there he felt that his presence was appreciated. He visited the Palais Ephrussi, and experienced the relief of "restituting a book, and a story, to a city that had thrown us out".

The Hare with Amber Eyes was reviewed in the TLS of September 3, 2010. A new illustrated edition came out last month. A selection of de Waal's artworks will be displayed at Waddesdon Manor from April 20, 2012.

December 13, 2011

Rock-hard Jersey Boys

The convention of theatre criticism is that everyone notices a show's opening. Few care about a closing. And fewer still care when a show rolls on night after massive-earning night all over the world.

Six years after its Broadway debut, Jersey Boys is one of the biggest theatrical hits of our time. Any TLS reader who is not a fan of Franky Valli and the Four Seasons (an easy group to find, I guess) will be barely aware that it exists.

Which perhaps does not matter except that when I saw it in London last week, it did trigger a few thoughts. Three years after opening here, the theatre was absolutely packed. The audience was permanently about to bounce out of the seats — and periodically did so. Not a whiff of recession anywhere. A terrific reminder that people will spend money if they are sure they are going to have a good time.

Certainty is often seen as akin to sterility. But the direction here was still as tight as a perfect first night. The cast was so well drilled you might think that a Chinese general was permanently parked in the stalls, any slightest deviation from the original will being punished by the Jersey Boys' less savoury gangland characters.

There are many so-called 'juke-box musicals'. But this one works — and has always worked — because of the simple technique of allowing each band-member to alternate in describing his disfunctional relationship with all the others. Nothing flashy — except the Seasons' suits. Nothing soft or slack. a rhythmically adjusting point of view. I left feeling that I could come back in another decade and it would still, rock-solidly, be there.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers