Peter Stothard's Blog, page 75

March 12, 2012

Man Booker, Maverick Sabre and Wish You Were Here

After two hard-reading days, I might normally find something, however small a something, on which to post a blog.

But in these Man Booker days, I read only new novels.

And a whole weekend of reading produces thoughts only for future sessions with my fellow judges next month.

The Chairman is in purdah, like Chancellors of the Exchequer once were before their Budgets.

I am saying nothing.

But on each weekend night I did hear a great musician, each one a gentle star from widely different generations.

Top of the bill, I guess, should be David Gilmour- who on Sunday at the Hammersmith Apollo concluded a Virtual 60th birthday party for a friend who had died young with a solemn acoustic statement of the thirty-seven year old Pink Floyd classic, Wish You Were Here. It could have been sentimental; it surely was not.

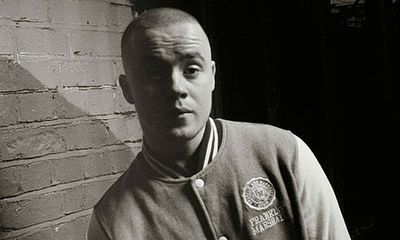

But only just below him was the four decades younger Maverick Sabre, who on Saturday night at the Roundhouse did much more than remind me why I blogged so enthusiastically about him here two years ago.

Half way through his set he stopped a fight in the crowd, calling up on stage two much older men with the words that this was not the kind of thing that happened at Maverick Sabre gigs.

He asked them to to shake hands with each other — and so, somewhat dazed and star-struck too, they did. There is a full description here from The Independent.

This seemed highly impressive to me. I've been at many a journalists' awards ceremony at which skill like that would have been useful.

I've been at Man Booker Prize dinners too where such diplomatic heft would have been reassuring to have in reserve.

This year?

We'll see.

March 8, 2012

Santorum and the Cicero brothers

BY PETER STOTHARD

I can barely hear the the words Super Tuesday without wishing I had been in Ohio or Georgia this week.

I can barely hear the the words Super Tuesday without wishing I had been in Ohio or Georgia this week.

For any political journalist (as once I was) it is the best of times.

Today I made a tiny contribution to the coverage in the Wall Street Journal with a piece on the Commentariolum Petitionis, a practical, cynical and eerily modern guide to winning votes that is commonly (and probably correctly) attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero's younger brother Quintus.

I thought of Robert Kennedy's help to JFK and Jeb Bush's for GWB and Roger Clinton's and Billy Carter's hindrances.

And I wondered what help the younger Santorum brother was giving.

I asked but no one seemed to know.

Is anything fraternal happening out there?

March 7, 2012

Politicians, historians and the Holocaust

DAVID HORSPOOL

Do you know about Godwin's law? You may not know it's called that, but the gist of it is: "As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches". Not only online, of course. There was an example of it this week, when the Prime Minister of Israel, Binyamin Netanyahu, speaking on Iran, held up a historic correspondence from 1944 between the US War Department and the World Jewish Congress, in which the Under Secretary of War gave reasons for his government's refusal to bomb Auschwitz.

Surely Godwin's Law doesn't apply to Israel and its Prime Minister? If anyone has carte blanche to invoke Nazi crimes, the perils of appeasement and to keep alive the memory of victims of the Shoah, is it not the leader of the country which rose from the ashes of those crimes? Absolutely, but that is no reason for listeners to Mr Netanyahu's speech to forget that when politicians use history, it is rarely in the way historians do. That is, they use those bits of the historical record that assist their argument, rather than sifting the evidence and seeing where it all leads them.

I do not presume to go into the case Mr Netanyahu was making for potential military action against Iran. I am ignorant of the details and TLS history editors are probably not the best people to pronounce on matters of international current affairs. But history is another matter. So let's concentrate on that.

Mr Netanyahu's historical point is that the Allies, specifically the Americans, could have stopped the Holocaust if they had bombed Auschwitz, and that the most shocking part of Under Secretary McCloy's refusal was his worry that such a policy might provoke "more vindictive action" from the Nazis. "More vindictive than the Holocaust?", Mr Netanyahu asks. Put like that, there can only be one answer, as the Prime Minister knows.

Yet the question of "bombing Auschwitz" remains a fraught one, historically. It did not become a tactical possibility until late in the war, when Aliied advances brought the camp and its railway line into range. It would have been extremely difficult to do, and would have had to have been carried out in broad daylight. Reviewing William D. Rubinstein's book, The Myth of Rescue, in the TLS in 1997, Professor Richard Overy, a leading authority on air power, wrote that Rubinstein was "right to be sceptical about what effect this might have had. Bomb damage for priority projects was quickly repaired; . . . It is unlikely that a single attack of dubious accuracy could have halted the extermination, though it might have had a significant political or psychological impact".

Not all Jewish leaders called for such action. A month before the request from the World Jewish Congress was made, David Ben-Gurion said "We do not know the truth concerning the entire situation in Poland and it seems that we will be unable to propose anything concerning this matter," though later, he was persuaded. Even the appeal itself was unclear as to how to proceed, or what the purpose of bombing might be. The request from Ernest Frischer, a member of the Czech government in exile, said:

"I believe that destruction of gas chambers and crematoria in Oswiecim by bombing would have a certain effect now. Germans are now exhuming and burning corpses in an effort to conceal their crimes. This could be prevented by destruction of crematoria and then Germans might possibly stop further mass exterminations especially since so little time is left to them. Bombing of railway communications in this same area would also be of importance and of military interest."

Is it not possible that, in the middle of an all-out assault on the source of Nazi crimes (this was 1944, after all), officials read that "might possibly stop" as just one more idea among many presented to them to hasten the end of the war for a portion of the population of Europe, when the aim was to rid all Europe of Nazi tyranny? The Allies had agreed that diverting resources away from their overall strategy was likely to delay the end of the war, not hasten it.

I am not arguing that Auschwitz couldn't have been bombed, or that Jewish lives couldn't have been saved; the case is unproven on either side. But what is certain is that nobody knew at the time, and pace the implication of Mr Netanyahu's comment -- that today, "The American government today is different", as if the US government of 1944 was unconcerned about the fate of the Jews -- if the refusal was wrong (and it is by no means certain it was), the letter he quotes shows that the error was not due to indifference or something worse, but to strategic miscalculation, something unavoidable in the middle of the biggest war the world has ever seen.

"Never again" is a sentiment that brooks no opposition, but we owe it to our predecessors to acknowledge that, yes, decisions about international policy seem hard now, at a time of relative peace, satellite technology, vast reams of information, and the certain knowledge of historic crimes. But they were almost inconceivably harder in the circumstances of 1944.

March 6, 2012

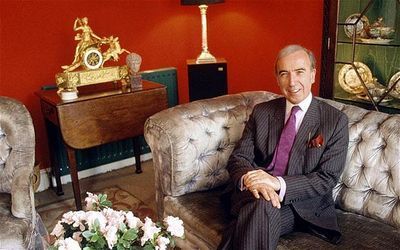

Norman the Magnificent

BY PETER STOTHARD

My friend David Hare, the aesthete and distinguished designer of interiors who lives in France, has just emailed me about the death of Norman St John-Stevas.

My friend David Hare, the aesthete and distinguished designer of interiors who lives in France, has just emailed me about the death of Norman St John-Stevas.

We were last month planning to arrange dinner with the unique Lord St John — but were now forestalled by a death of which, I must admit, I had been unaware till David told me of it.

Perhaps I need to keep up with the obits more. The TLS does not require constant vigilance to rumour or reports or what we used to call 'the wires' but which now have other names.

Nor does the Man Booker Prize, whose chairmanly duties are currently quite demanding, nor the Classical Association which demands of its president a little too.

But none of that is quite an excuse.

I see that there are already fine tributes this morning to Norman who, amongst his other grander glories, chaired the Booker Prize in 1985 and had given me a liitle good advice which, like all Booker communications, must remain confidential even in death.

I told him that I did not think these days too much about the Thatcher era, the time when we first met. Since I have watched barely more than a dozen films in all my life (he was a bit shocked by that) I am unlikely to see Meryl Streep in the role.

So deaths of political friends (how few of them there really are) are an excuse for a little nostalgia, especially if their news arrives a little late from France.

Norman was magnificent in many ways as a subversive Cabinet minister at the beginning of the Thatcher government. But he was an unusually magnificent source in my earliest reporting days.

As a boy from Chelmsford I had once been his constituent. But he was not a great lover of the place and thus, while we shared that view, it was only a small help. His words on the County Town of Essex were merely wittier than mine.

Nor was I on his side of the big political arguments — or even particularly against him — at a time of the intensest divisions. He thought my position in this regard to be ill-starred but entirely reasonable. Anyway, I was a very junior political journalist for The Sunday Times at the time and it hardly mattered what I thought.

I did, however, always listen carefully to what he said. My words with him were my first, and never equalled, experience of being told the opposite of what those words, if seen in print or over heard, would seem to mean.

Norman was a master craftsman of being a source. I suppose that any examples of that should remain Man-Booker-confidential still.

When I later became editor of The Times he both congratulated and claimed a little credit for my advance. He claimed a little payback from time to time when there might be stories about art or architecture that might otherwise have been neglected.I was happy to oblige.

I most of all this morning wish that David Hare and I had had that supper.

February 23, 2012

Being a poet

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

T. S. Eliot once said that he could understand wanting to write poetry, but not wanting to be a poet.

At a Royal Society of Literature event on Monday – which took place in a luxuriously comfortable lecture hall at the Courtauld Institute, Somerset House, and consisted of conversation, readings, question-and-answer session and wine – David Harsent asked his fellow poets Lavinia Greenlaw, Emma Jones and Ahren Warner what they thought about that.

Harsent himself made the point that, since almost all poets need day jobs, to say "I'm a poet" is to make a kind of statement. Often the response is "startlement, becoming puzzlement, becoming a kind of sneer, followed by a fear that poetry might become a topic of conversation".

Warner tends not to use the phrase. Jones does occasionally, sometimes for the sake of owning her addiction, as she put it; and it amuses her to write "poet" as her occupation on landing cards: "they look at you as if you're a unicorn crossed with a serial killer". But she often has difficulty with what they say next: "What do you write poetry about?"; "Why?"; "I didn't know there were poets any more". . . .

Greenlaw has come up with a beautifully evasive stock answer to the "What do you write about?" question: '"Whatever the good Lord tells me to write about".

As she pointed out, poetry occupies a strange territory in society: it is "obscure but fundamental". She is irritated by the use of the word "poetic" to mean vague, whimsical, flighty; "poetry can capture those things", she said, " – but with great precision". She is also troubled by the lack of interest in what she called the joy of the difficult ("having to stay still and pursue something") – the expectation that poetry should be accessible, "perform for you", and make you feel fuzzy.

There is also the problem of money. According to Harsent, the ideal day job for a poet is "bank robber". He has worked as a shop assistant in a bookshop, a publisher, and a commercial writer, and has always regarded such jobs as necessary evils; he dislikes "broken, fractured creativity" and craves long stretches of uninterrupted writing time.

Jones identifies with this to some degree – she gave up the idea of going into academe full-time and writing on the side when she found that she wasn't a good mental multi-tasker – but she finds that long residencies can become a "terrible luxury" as "empty time stares at you across the poker table". (She uses simple I'm-not-really-working techniques, such as lying on the floor instead of sitting at a desk, to take the edge off the anxiety.)

Greenlaw, who teaches part-time at UEA as well as working on radio dramas and documentaries, among other things; and describes herself, in her hectic busyness, as "a one-woman restoration comedy", acknowledged the difficulty of "protecting the poems". But she thinks that life outside them is important – partly because, after three or four days' writing, she starts to go a bit mad. (It's a pity she wasn't asked "In what way?".)

Jones feels at times that writing poetry is "pretentious, self-indulgent, fundamentally useless, self-aggrandizing"; but she feels compelled to continue – "and if it gives ten people pleasure . . . ". Eliot's words encapsulate what came through clearly from all these poets: that the appeal is not the image, or the lifestyle, but the writing. "Nobody carries on unless they have to", said Greenlaw. "It's frightening and difficult . . . . You never expect to make money . . . you just do it".

February 22, 2012

Marie Colvin: she went, she saw, she verified

Being with Marie Colvin was always a reminder of why to be a journalist might be important.

Even to see her black eye-patch across a crowded party was reminder that journalism mattered.

Whatever happens to our trade in these so unnecessarily turbulent times, the requirement to go, to see and to verify will remain at its core.

Marie Colvin went to Homs for The Sunday Times to see and to verify - and she has been killed by a shell.

So much more to be said - but that is the summa rerum on this sickening day.

*

From the TLS archives: Marie Colvin's Letter from Kosare, published in 1999.

February 20, 2012

Pirates in Joyceland

By J. C.

Several literary estates came out of copyright on January 1, 2012, under the seventy-year rule. You may now, if you are so inclined, reissue the works of Hugh Walpole without first seeking permission (Hans Frost, for example, or Wintersmoon, or any of thirty other perhaps unjustly neglected novels); or of Sherwood Anderson; or the once-influential Elizabeth Madox Roberts.

The works of James Joyce are a different matter.

All the major books are in print, and likely to remain so – but that needn't stop you bringing out your own edition of Finnegans Wake. There is, moreover, a "huge amount of non-published material" in the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, according to the Foundation itself, waiting to be edited. For years, Joyce scholars have visited the Foundation, made notes, then wrestled, often in vain, with the Joyce Estate and its executor, Stephen James Joyce.

Copyright law permits a certain amount of free quotation under "Fair Dealing", but the provision is vague. A snatch of dialogue from Joyce's versions of plays by Gerhart Hauptmann? Maybe. A paragraph from an unpublished letter? Risky. Ever since Salinger vs. Random House, biographers and scholars have trembled before taking even a sentence from unpublished work, fearing lawsuits or pulping. Some estates do nothing to dispel the falsehood that extracts from published writings also require permission.

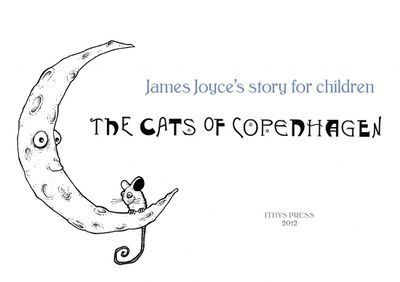

A Joyce scholar of our acquaintance copied out for his own use what he calls "an extended joke" from a letter in the Zurich Foundation dated September 5, 1936. "It is exactly 242 words long." The letter is addressed to Joyce's four-year-old grandson, Stephen (the same). The little anecdote is now at the centre of a storm about copyright, publishing rights, and the desire of the Foundation to remain in control of Joyceland.

It appears that Anastasia Herbert, or someone acting on her behalf, also copied out the words. Ms Herbert's Ithys Press has published all 242 of them as a book – "a masterpiece of the book-making arts", in her words – which now stands as an uninvited addition to the Joyce corpus: The Cats of Copenhagen. She sees it as "a tribute to Joyce's creative genius"; the Foundation sees it as intellectual property theft, and a grave discourtesy.

Ms Herbert did not tell Zurich what she was about to do because, she says, in Joyceland, to seek permission is to seek trouble. She cites the injunction gained by the Estate preventing the publication of Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century, which "caused serious problems" for Cork University Press. Doubtless, the Joyce Estate cared not a fig for their problems. Why, Ms Herbert asks, should she walk into a trap of her own making, by asking permission to publish 242 words by an out-of-copyright author?

Yet the courtesies are worth observing. A fierce ally of the even fiercer Estate or not, the Zurich Foundation is indispensable to Joyceans. Certain bequests come with restrictions which, as a result of Ithys Press's action, are sure to increase. We have the text of The Cats of Copenhagen before us. Ms Herbert sees in it a "keen, almost anarchic subtext", though where she gets that from goodness only knows. It is not a composed "story" at all, rather a charming scribble to a little boy, the likes of which many grandfathers have written. Two Ithys Press editions are published, at 300 euros and 1,200 euros.

February 16, 2012

Making it up?

BY ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Pierre Bayard, the man who gave us the enjoyable Comment Parler des livres que l'on n'a pas lus? (How To Talk about Books You Haven't Read), has done it again. This time he has turned his attention to travel with the equally provocative-sounding Comment Parler des Lieux où l'on n'a pas été? (How to talk about places we haven't been).

The title of the series in which the books appear - Editions de Minuit's "Paradoxe" - might have been invented for Bayard. Note too the teasing question mark in the French, which the English translator thought prudent to omit, removing the ambiguity in the process. The earlier book became a surprise bestseller in France, with more than 80,000 copies sold; how many of those buyers bought it in the mistaken belief that they had picked up some sort of self-help manual? Far from being a mere farceur, Bayard teaches literature at Paris VIII and is a practising psychoanalyst.

In his earlier book, he was shamelessly keen to let us know about all the books he hadn't read, had merely skimmed, or had forgotten - this didn't prevent him from discussing them in some depth. This time he doesn't mind revealing either that he has travelled little. But, as he points out, Immanuel Kant famously never left his home town of Königsberg, taking the same walk every day; this apparently didn't prevent him from writing about other countries. We will have to take his word on that one. Bayard dedicates his book to this "stay-at-home traveller par excellence".

Of course this isn't really a book about how to convincingly pretend you have been to Vietnam when in fact you haven't. Rather Bayard discusses travel writers through history: Marco Polo, for example, wrote about China, but Bayard follows the Sinologist Frances Wood in believing that he never went there. Bayard wonders whether he ever made it as far as Constantinople. None of this devalues what he wrote: he will have got his detailed accounts of life in China from other travellers.

Equally Chateaubriand can't possibly have travelled as extensively in North America as he claimed in the time that he was there. Bayard provides some of Chateaubriand's fantastically detailed and vivid descriptions of Mississippi and Florida, but did he ever get there? According to Bayard, these are "in all probability completely invented".

The novelist Edouard Glissant, on the other hand, is quite open. No longer able to travel long distances, he sent his wife on a trip to Easter Island - about which he was intending to write a book. She came back with detailed notes which he fashioned into a book (published in 2007, under joint authorship). Bayard even comes to the defence of Jayson Blair, the New York Times journalist who was rumbled for filing reports from places he hadn't been, on one occasion a few blocks down from where he lived.

Bayard has some excellent pages on Blaise Cendrars, the Swiss writer who blended travel fact and fiction better than anyone. Did he really travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway, about which he wrote so poetically? It's unlikely, thinks Bayard. At the time Russian troop movements by rail would have made such a journey by a foreign traveller almost impossible.

Does any of this matter? Not hugely, but there is something seductive about Bayard's literary games. They encourage us to view books in a different, more liberated way. What will he turn his attention to next?

February 9, 2012

O the competition!

Any chance of your posting a blog?

Any chance of your posting a blog?

Our web editor this morning was polite but firm.

It is true that I have not posted since December 20.

But I was away in Argentina for a while - and since I've been back in the country I have not got back into the habit.

And then there is the fierce new competition of our TLS internal market.

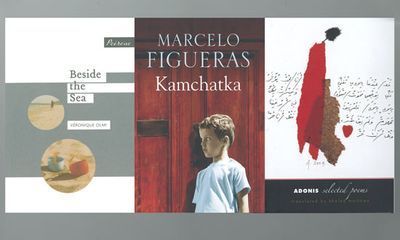

On Monday, for example, I presented the prizes for the Translation Awards. I have posted on this in the past, nornally on some failure of mine to pronounce properly the name of the Flemish or Arabic winners.

But before I had even begun to collect my thoughts about why Adonis is tipped to win the next Nobel Prize for literature (it cannnot just be because he is Syrian), my colleague, Thea Lenarduzzi, had posted an immaculate account of the evening.

Then, on Tuesday we had a TLS toast to Dickens in the Calthorpe Arms. But I am not going to compete with the contents of our excellent 200th anniversary edition.

The Calthorpe toast from us all, as I recall, was 'to raised eyebrows' but I don't quite remember why.

Afterwards, Mary Beard and I went together to the Omnivore Hatchet Job of the Year Award in Soho - for which she had been shortlisted for her very restrained views on Robert Hughes' Rome.

It was great night. We both enjoyed the comic duet by the young Omnivoristes, Fleur Macdonald and Anna Baddeley, about the rise and fall of the literary logroller. Maybe they will put up a podcast or whatever.

But by the time that I reached the office next morning Mary had already posted on the event and the plot (and put up a photograph, republished above without fee!), not even leaving me the culinary sponsorship by the Fish Society upon which to opine. By 10 am my inbox was filled with Facebook wails from a writer who did not like being hatcheted and her friends who told her it was unprofessional to complain.

Not much more to say on that. And so many people saying it.

Internal competition? The TLS is becoming like the Conservative vision for the NHS.

So what now? I have been spending a good deal of time on novels for this year's Man Booker Prize. But the Chair of the Judges can hardly post a commentary on that without attracting unwelcome Omnivorist attention.

Tonight I am off to the Harold Pinter theatre for the opening of Alan Ayckbourne's Absent Friends.

With any luck I will be the only TLS blogger in the aisles.

February 7, 2012

Lost in Translation

By THEA LENARDUZZI

The revolving doors at Kings Place, London N1, were put to the test last night with around 200 people pirouetting or hurtling in from the cold for the award ceremony of the Translation Prizes 2011. Sponsored by the TLS, as it has been for many years, the night was a welcome reminder of the importance of reading books in translation, but also those perpetually under-sung literary heroes, the translators.

I came from just around the corner for the event; others had travelled much further to collect their prizes and take a bow, or to hear the winners read extracts from their books. First was Khaled Mattawa, straight off the plane from Tripoli, to accept the Saif Ghobash-Banipal prize for his translation of the Selected Poems of Adonis. His reading – "I add height and depth but how do I find my way . . . how do I find my direction . . . . And what do you want from me, son, O son?" – set the theme, crystallizing the web of dependence that links writers, translators and readers, even as a need for independence of voice might spin them in a different direction. Adriana Hunter, reading from her winning translation of Beside the Sea by Véronique Olmi, provided what seems a fitting coda to Adonis's/Mattawa's dilemma: a troubled single mother and her two young sons are climbing the six flights of stairs to their hotel room, "Perhaps if there had been more light we'd have felt more like it".

After the readings, Sean O'Brien stepped onto the stage to deliver the Sebald Lecture, being sure first to thank the stage management for their "delicate work" in rearranging the furniture to introduce a Parkinson-esque set of chairs and coffee table, and then point out an essential re-arrangement of his lecture title: "Making the Crossing: The poet as translator" should be "Making the Crossing: A poet as translator"; "I have nothing to say by way of theory of translation, only my own experience".

And O'Brien's experiences are certainly varied, careering from adolescent readings of Rilke in a (poor) translation, to producing his own version of Dante's Commedia (stemming, as I understood it, from some sort of dare by Don Paterson); a verse translation of Aristophanes' The Birds (to tie in with a production by the National Theatre in 2003); and Postcards from the High Seas by the Creole poet Corsino Fortes. Now, he is turning his attention to the Spanish Golden Age and the work of Pedro Calderón, written entirely in rhyme, with seven different varieties of verse and enough "bravura" to send many a translator running for the stage door.

With all of these, the challenge is to navigate between two sorts of translation: "faithful but uninteresting" and "interesting but unfaithful" (that push and pull between dependence and independence, again). For some endeavours, "accuracy is everything", for others it can be left below deck or on land. Translation is unavoidably and necessarily "an impure art". The task of translating a poem and producing something that is self-buoying rather than tied with ropes and notes to the original is likely to induce sea-sickness in many. O'Brien, for example, "can get by" in French and German but is eager to begin a project on Lithuanian poetry. What if you get it wrong? What if you miss the point? "So shoot me", he says . . . .

It strikes me that sitting at the back of the large, church-like auditorium in the basement of Kings Place is in some small way similar to the anxious experience of translating. I can't make out every word, I'm petrified I'll miss the "most important part", I have no way of checking where line breaks are or of double-checking quotes (I scanned Adonis's poems this morning for the "son, O, son" that I felt sure my eye would spot, but did not). But there is some comfort in O'Brien's lines on the necessity of translations: "If you want a thing to live, you carry report of it". As O'Brien said, channelling the actor Harrison Ford "You can type this shit but you can't say it", or, in my case, "you can say it, but I can't type it." Reporting, like translating, is a form of interpretation. So shoot me.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers