Intellectual peat

"During the Parliamentary Session LITERARY SUPPLEMENTS to 'THE TIMES' will appear as often as may be necessary in order to keep abreast with the more important publications of the day."

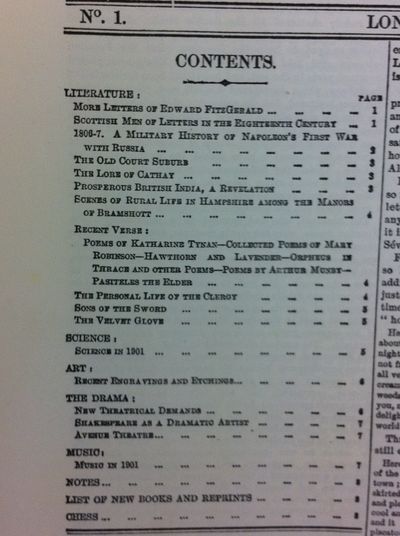

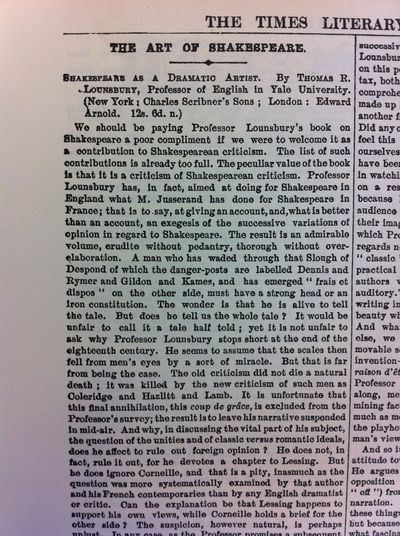

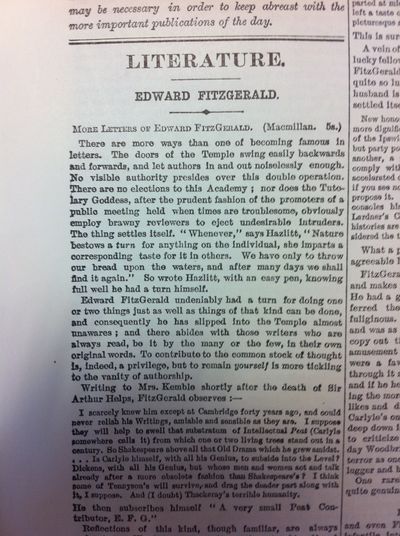

That's how the TLS announced itself on January 17, 1902, when the first issue appeared. (Starting out on a new TLS blog has sent me back to look at the useful office copies of the paper itself, as in the photographs below.)

Apparently, in 1902, "to keep abreast" of the important books meant keeping abreast of books about Scottish men of letters in the eighteenth century ("eminently readable"), the "case against British government in India" ("inconclusive") and science ("Professor Gamgee's investigations into the magnetic qualities of the blood . . . touch physics on the one hand and physiology on the other"). It meant F. Loraine Petre's account of Napoleon's first war with Russia (". . . fills an important gap in English Napoleonic literature"), as well as two attempts to write "a good Napoleon novel" ("it is a story in which all will find something to their taste"; "a fascinating little heroine . . ."). It meant opening a survey of half-a-dozen new volumes of poetry with the (rueful?) observation that "There is no slackening in the current of contemporary verse . . .".

Some cast their contemporary opinions as the views of posterity. The reviewer of Shakespeare as a Dramatic Artist by Professor Thomas R. Lounsbury, for example, predicted a future in which the scholars of 1902 might seem as quaint as their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors did to them: "What Rymer seems to Professor Lounsbury the Professor may seem to some other Shakespearean commentator two centuries hence".

But perhaps the most striking insight into the distance between them and us, then and now, 1902 and 2011, comes in the very first review in the issue, on More Letters of Edward FitzGerald.

Here a letter is quoted in order to show FitzGerald's awareness of what Posterity would soon do to his writing friends and other contemporaries – how it would reduce them, bar one or two, to a "substratum of Intellectual Peat":

"Is Carlyle himself, with all his Genius, to subside into the Level? Dickens, with all his Genius, but whose men and women act and talk already after a more obsolete fashion than Shakespeare's? I think some of Tennyson's will survive, and drag the deader part along with it . . . . And (I doubt) Thackeray's terrible humanity."

FitzGerald signs off as "A very small Peat Contributor, E. F. G.". But he didn't seem quite so small to the reviewer of these posthumously published letters. Although the review begins with a vision of a kind of literary Temple of Fame, with doors that "swing easily backwards and forwards, and let authors in and out noiselessly enough" (an appropriately library-like conceit?), the conclusion turns to FitzGerald's masterpiece, The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. What would have happened if, say, every copy of this ingenious "paraphrase of Omar" were to be "destroyed by fire to-morrow"?

Why, "we very much doubt whether there is a town in England of over 40,000 inhabitants which could not produce a sufficient number of citizens whose united memories would prove equal to the task of dictating the entire version to a type-writer".

If only a town with the requisite population had gathered around the typewriter to put this fine piece of praise to the test. . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers