Sylvia Plath, the doodler

Gaps in Sylvia Plath's story will, of course, always remain. Emphases, like manuscripts, can be misplaced. Shadows grow and details fade, so that the fact of suicide and the acknowledged themes in her work – rage, pain, depression, redemption, "the horror of man's being a creature that dies" (Derwent May reviewing Ariel, TLS November 25, 1965) – displace the everyday experiences of a young student from Smith College travelling to Paris with her boyfriend in the early 50s; of a newlywed honeymooning with Ted Hughes in Benidorm in 1956; of a mother's "wondering pleasure in her children, or of gratitude when 'the world / Suddenly turns, turns colour'" (another aspect of Ariel described by May in the same review).

At an exhibition of her drawings at the Mayor Gallery in London we see Plath the sketcher, the doodler, the draughtsman. This is the woman described by Hughes as never more radiant than when she had spent a day indoors drawing a still life.

Many of the works, pen and ink on paper, will resonate with readers: an abandoned pair of high-heeled shoes called "The Bell Jar" evoke the part in her novel when Esther Greenwood, contemplating death by drowning, kicks off her shoes on the beach and leaves them facing out to sea, "to be like a sort of soul-compass after I was dead".

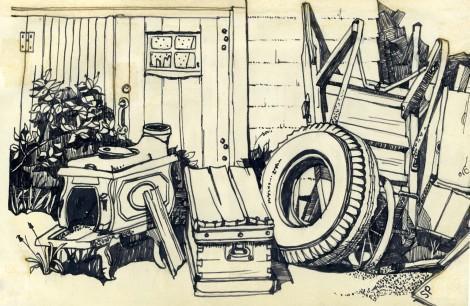

There are happier, postcard-like images, too, of small Spanish fishing villages, the rooftops of the Left Bank in Paris, rusty teapots and "The Pleasure of Odds and Ends":

In 1968, the literary critic David Holbrook complained that his "serious critical work" on Plath was being stifled by Plath's executor Olwyn Hughes (her sister-in-law) who, he said, refused even to look at his proofs of Dylan Thomas and Sylvia Plath and the Symbolism of Schizoid Suicide. Ms Hughes replied that she had made no such statement but that she was concerned about the form that Holbrook's criticism took: "He writes for instance 'one has to examine Sylvia Plath's work while remembering that some of it will be insane", and describes The Bell Jar as "a horrifying autobiographical account . . . of an American girl who goes mad."

Holbrook's book disappeared – or at least his original version did. His Sylvia Plath: Poetry as Existence (1976) was described by Anne Stevenson in the TLS as "clumsy" and "a little heavy-handed" and she warned: "we must not forget, though, that schizoid as she may have been, Sylvia Plath was above all a poet." (Stevenson went on to write her own version of Plath in Bitter Fame: A life of Sylvia Plath, 1989.)

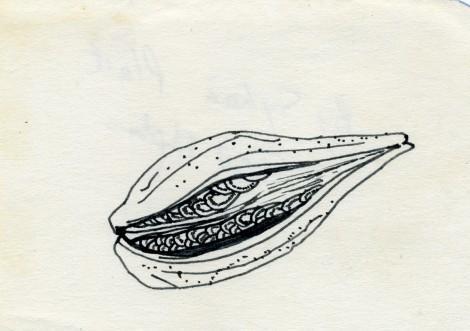

But Plath's drawings were more than just diversions or decorative additions to her words – sometimes they were intended to take centre stage. Having sketched a composition of three sardine boats in Benidorm, she wrote "I'm going to write an article for them to send to the Monitor". If only these pictures had been on show in 1968 during the Holbrook–Hughes affair. How tempting to respond to Holbrook's psychological profiling by pointing out, "No, Sir, look – this is what a study of a nut looks like":

All images are by Sylvia Plath, copyright Frieda Hughes, courtesy of the Mayor Gallery.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers