Peter Stothard's Blog, page 52

November 9, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

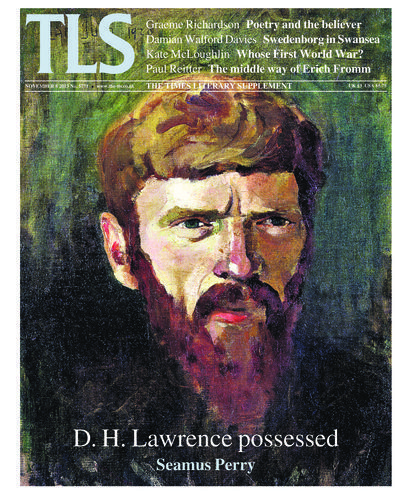

In his preface to an American edition of his poems, D. H. Lawrence contrasted the “measured gem-like lyrics” of Shelley and Keats with the kind of poetry he himself wrote and admired: a poetry of “living plasm” with “nothing crystal, permanent”. Seamus Perry reads a new edition of Lawrence’s collected Poems and finds that, though some might wish for less, taking Lawrence the poet all in all is important to seeing “the very odd sort of writer of verse he was”: one whose poetry claims for itself “the unanswerable quality of merely being possessed by the life-forms it celebrates”. Lawrence was briefly associated with Imagism, and it is to that vastly influential movement and its offshoots that we owe what Graeme Richardson identifies as the three “sacred tenets” of modern poetry. And these allow little room for the sacred, or for religious faith – faith such as that professed by Christian Wiman, a poet and until recently the Editor of Poetry (Chicago), who at the age of thirty-nine was found to have a rare and incurable cancer. But according to Richardson “the profound truth” in Wiman’s latest book, a memoir, has less to do with illness or belief than with his “mistrust of writing, his meditative, circling suspicion of his vocation as a poet”. Paul Griffiths, reviewing the new book by the Hungarian László Krasznahorkai, finds that it is about, precisely, “the presence of the infinite, the sacred in human affairs – or its absence”; and that in it Krasznahorkai tells “the same story as always: that we live in a disgraced world”.

From a position which sought to marry psychoanalysis, Martin Buber and sociology, Erich Fromm achieved immense popularity and success with books such as Escape from Freedom and The Art of Loving. He never, though, “achieved his primary political goal of lasting international peace sealed by love”. According to our reviewer Paul Reitter, the wait for a major biography, at least, “is over”. The wait is over, too, for Morrissey’s autobiography – “ornate, windswept, elusive yet never tricksy”, and sometimes delivering vitriol “via a hose”, it will not, says Gwendoline Riley, disappoint his loyal following.

Alan Jenkins

November 7, 2013

The Goncourt prize 2013 . . . and 1913

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

This year’s Prix Goncourt (France’s

most prestigious literary prize, value €10) has gone to Au Revoir là-haut by Pierre Lemaitre

(published by Albin Michel). The novel is set in post-First World War

France, where, according to Macha Séry’s description of it in Le Monde this week, “impostors triumphed

and capitalists got rich on the ruins”. One of the judges, Bernard Pivot,

praised the “cinematographic” qualities of the novel. Lemaitre has up until now

been a successful author of that very French genre, the polar. His new book, which has already sold 40,000 copies since

publication in August, could hit sales of 400,000 on the back of the prize –

that, at least, is the average sale figure for winning books.

One of the ten

judges, Pierre Assouline, has just published

an entertaining history of the prize: Du Côté de chez Drouant: Cent dix ans de vie littéraire chez les Goncourt (Gallimard). The title refers to

the restaurant where the judges traditionally meet for their deliberations.

The Académie Goncourt,

Assouline tells us, was set up by the Goncourt brothers as a counter to

Richelieu’s Académie française. Assouline insists that there is no “style Goncourt” although the

existence of the adjective “goncourable” to suggest a book ideally suited to

win the prize (in the way that some novels seem like obvious Booker Prize material)

would seem to indicate otherwise. When Alexis Jenni’s novel L’Art français de la guerre was published in

August 2011, I immediately had a hunch that it would win the Goncourt, and sure

enough it did: a big book with an arresting title, chronicling France’s troubled

history in Indochina and Algeria, written by a lycée prof in Lyon – it ticked all the

boxes.

When one of the judges Michel Tournier

was smeared with tomato ketchup one year as he emerged from the Drouant it was

in protest at a perceived stitch-up (it should be said that Tournier has always seemed the most independent-minded of reader-critics): the judges (and judges of other book

prizes) have in the past been accused of pandering to the big three Parisian

publishing houses, Gallimard, Grasset and Seuil, known as “galligrasseuil” (a mot-valise). By my calculations they

have walked away with 56 of the 110 Goncourts, many of those going to Gallimard, whose pre-eminence in French publishing has no equivalent in Britain or the US.

Editions de Minuit traditionally don’t submit their books for prizes, which

didn’t prevent Marguerite Duras from winning the Goncourt in 1984 with L’Amant. The Goncourts stipulated that

the prize should go to youngish authors, but Duras was 70 – maybe it was more

of a lifetime achievement award. The celebratory lunch at the Drouant was

attended by her friend President François Mitterrand.

Just as the astonishment at the award

of the Booker to Hotel du Lac by

Anita Brookner in 1984 ahead of Martin Amis’s Money can never quite subside (who were the judges that year?), the

Goncourt judges excelled themselves by garlanding Paule Constant’s tame Confidence pour confidence in 1998 ahead

of Michel Houellebecq’s masterpiece Les

Particules élémentaires. When Houellebecq won in 2010 with La Carte et le territoire, one of the

judges Patrick Rambaud apparently didn’t like the book but voted for it “so

that the Goncourt can be done with Houellebecq once and for all”.

Assouline, a novelist himself, as

well as being a prolific biographer, critic and blogger, has only recently

joined the panel of judges. He’s in for a long haul: over its 110-year history

there have been a mere 58 judges (very different from the Booker Prize, for

example, which calls on five new judges every year). Assouline lists the ten couverts or places (imagine a large

round table), of which he occupies the tenth. His predecessor, Françoise Mallet-Joris,

was in situ for 41 years. The distinguished cast has included J.-K. Huysmans,

Colette – it’s worth pointing out at this point that only eight women have won

the prize, and that one of them, Edmonde Charles-Roux, who won in 1966, has

been a judge since 1983 and is now présidente) – Jean Giono,

Louis Aragon, Raymond Queneau and Michel Tournier, who stood down after 38

years in 2010 (that looks like him on his feet with arm raised in the photo

below, taken in 1978). Tournier was himself a winner in 1970 with Le Roi des aulnes.

I thought it would be interesting to

check out the novel that won the prize a hundred years ago; somebody else must

have had the same idea, because it has been reissued in an anniversary edition:

Le Peuple de la mer by Marc Elder

(not to be confused with the British conductor Mark Elder) is published by

Marivole who tell the reader that the book bested Alain-Fournier’s

Le Grand Meaulnes (true) and Proust’s

Du Côté de chez Swann (not true).

Assouline points out that one of the judges, J.-H. Rosny talked about a “livre

de grande valeur”, but that it stood no chance as Proust didn’t submit it to

the judges.

Elder’s novel is set in a fishing

community in Noirmoutier on the west coast of France, where the wind sweeps

across the dunes of the Vendée. Life

is hard and precarious – fishing boats are regularly lost at sea, and in a grim

foretaste of the carnage to come, these sacrifices are made in the name of

“Honneur-Patrie”; heavy drinking is rife and there is much energetic coupling

in the dunes: “Les belles nuits de printemps et d’été, les filles et les gars

se rejoignent dans les falaises de la Corbière, sitôt passé les dernières

maisons du village. Les filles qui poussent en plein vent sur ce coin d’île ont les joues tannées,

les mains rudes, les muscles forts, le sang chaud. A partir de la puberté, ells

portent le désir éclatant dans leurs yeux et le remuent autour des reins parmi

les jupes”.

The book is rich in local dialect and

nautical and marine terminology: among words I don’t recall coming across

before are “le coaltar” (coal tar), “la salicorne” (samphire or saltwort) and “la

yole” (skiff or yawl). I enjoyed the book, and learnt from it.

November 6, 2013

The e-book made real

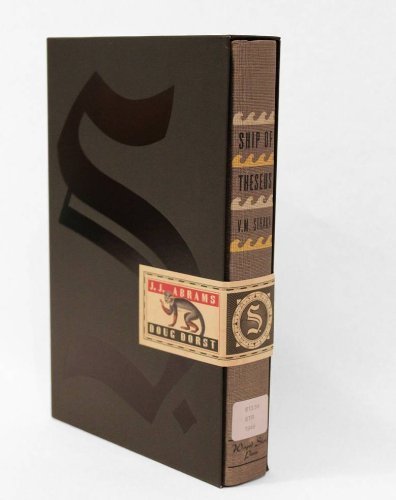

J. J. Abrams, the creator of Lost

(that “theological”, “mythological”, “numerological”, “dualistic”,

“apocalyptic”, popular TV series) has “conceived” of a book. Doug Dorst has

actually written it and Canongate have duly published.

B. S. Johnson’s novel in a box The Unfortunates, both Nabokov’s Pale Fire and The Original of Laura, the study of marginalia, Tom Phillips's book-as-art Humument – these might all be seen as influences on Abrams’s conception. But in

fact, he says, he “conceived” of S simply when he found an abandoned book in an

airport, annotated with a note to the future reader.

Here is the shape of his realized

conception: a cardboard sleeve marked with the letter S and a monkey and a ship.

The sleeve contains a convincingly battered library book, with all the library

stickers and stamps you would expect, both inside and out. The book is called

Ship of Theseus and is written by the mysterious V. M. Straka. It tells the

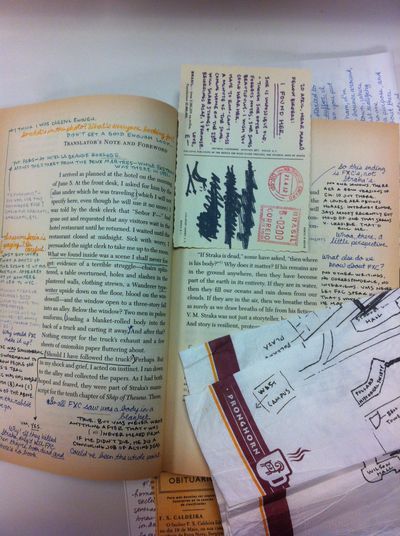

story of a captive man with no memory. When you open the book you see that it

has been annotated by its past readers. The whole printed text is littered with

handwritten conversation, doodles, declarations. Then there are the things that

fall out of the book, a paper napkin from the Pronghorn Java coffee shop on

which someone has drawn a map of a university campus. Newspaper articles,

lists, photos, postcards, all meticulously reproduced, are kept between the

pages. This is the book as beautiful object.

It doesn’t take long to work out that

the annotations are supplied by just two characters, Jennifer and Eric, over

several years. They are obsessed, in turn, with each other and Straka, the

author of the book.

You have to decide for yourself how

to go about reading this. One reader looked at me in patient miscomprehension

when I asked if he was reading the “novel” first, or the “play” set on top of

it in the marginalia. He was reading everything at once, of course, because that

is the only way. And one of many.

The thing is – of course – you can’t read

this on a regular Kindle. S is a kind of love song to the physical book and

to those things we love about physical books that you can hold, fold, and store

things in.

You can read S as an e-book on an iPad or a Kindle Fire, but in that

format the pull-outs and design detail – the way an address on the back of a

postcard grins through the crossings-out of violently applied black felt-tip

pen, for example – are unremarkable. We have come to expect additions in the

electronic versions of texts. In e-books, pictures and animations are used to

“enhance” the “reader experience” and authors are invited to think of new ways to

exploit the medium.

Perhaps what is remarkable about this, then,

is not that it was conceived of, but that it was printed. Because this is an

e-book, made real; it is a love song as much to animation and interactivity

as to library books and what their readers add to them.

The e-book made real: You will be

amazed by the quality of the screen resolution.

November 4, 2013

The poets at war (and in anthologies)

By MICHAEL CAINES

Remembrance Sunday approaches – the moment when newspapers make the costly mistake of forgetting that not all war poets are out of copyright (Robert Graves, for example, only died in 1985), and others, monotonously schooled in Wilfred Owen et al, groan at the familiarity of it all, and think of Captain Flashheart in Blackadder Goes Forth, sick, or so he claims, of “this damn war: the blood, the noise, the endless poetry”. . . .

Others, less cynical, more respectful of the obvious centenary (war being declared on July 28, 1914), will pay the full price of £14.99 for one out of this autumn’s advance guard of war poetry anthologies (and to think they could be paying a few pounds less for a proper new collection of verse, John Greening’s To the War Poets): Michael Foss’s (reissued) Poetry of the World Wars, Tim Kendall’s Poetry of the First World War, and Carol Ann Duffy’s 1914: Poetry remembers.

There should be more, in greater depth, about this subject in the TLS itself in due course, starting with a review of Randall Stevenson's Literature and the Great War 1914–1918 in this week's issue. For now, though, I’ll just note that Tim Kendall introduces his selection from In Parenthesis with this paradox: “Among the most significant poets of the War, David Jones proves by far the most difficult to anthologize”.

In another literary context, such a statement might seem bizarre – but Kendall’s anthology is in fact exceptional in acknowledging that other kinds of poetry exist besides short, anthology-friendly and often relatively undemanding lyrics. (Short in this context meaning under a page, two at the most.) Foss’s Poetry of the World Wars ignores Jones altogether.

Generally speaking, as my colleague Robert Potts has eloquently argued, anthologies tend to be allergic to complexity, especially in long poems, and to the kind of poetic complexity that works across a unified volume by a single writer. Compilations produced since 1918 can sometimes make it seem as though the Iliad never existed. David Jones, incidentally, started writing In Parenthesis around 1928, when Robert Graves and Laura Riding published their Pamphlet against Anthologies.

In Parenthesis, to take a prime example, is closer in spirit to the work of one of its most ardent admirers, T. S. Eliot, than to the more “accessible” or “traditional” verses of, say, Rupert Brooke or Edmund Blunden. Its significance does not lie in providing easily digestible poetic soundbites.

How then is it best for an anthologist to arrange the borrowed wares? Foss’s Poetry of the World Wars organizes its poets in historical phases: “World War One” opens with “Call to Arms: ‘Men Who March Away’” (featuring Hardy’s “Men Who March Away” and Brooke’s “The Soldier”), before moving on, through “Combat”, “Disgust” and the rest, to the aftermath. “World War Two”, after a brief interlude, follows a similar pattern. Two more distinguishing features: the book is illustrated, although not, apparently, by anyone who needs an acknowledgement; and it tells you nothing at all about the poets as individuals apart from what you might infer from the poems themselves.

That reticence about biographical information and the anti-individualistic structure of the book contrast with Kendall’s Poetry of the First World War, in which the poets take precedence over historical events in the orthodox way, being ordered by year of birth (1840 to 1898) and confined to separate sections – anthologies within the anthology. Hardy provides the opening number here, too, and the book closes with a selection of anonymous “music-hall and trench songs” – but thanks to Kendall’s headnotes, you can also read, say, the poems of May Wedderburn Cannan in the context of her life, ruined as it was by the war that she, who served both in a soldiers’ canteen in Rouen and for MI5 in Paris, had continued to support: her fiancé, the son of Arthur Quiller-Couch, would hardly have died of pneumonia in Germany, in 1919, if it hadn’t been for his military obligations. Walter de la Mare reviewed her collection of that same year for the TLS, and found it artless yet “full of tenderness”.

In 1914: Poetry remembers, meanwhile, thirty-odd twenty-first century poets offer companion pieces to poetry and prose by a wide range of war poets, a few of whom have been selected twice (one of them is Ivor Gurney, my own favourite among the war poets). This means that the “anthologists”, with Carol Ann Duffy at their head, slightly outnumber the “anthologees”. There are poems concerned directly with the First World War, with Private Isaac Rosenberg “writing his poetry by candle ends” (Elaine Feinstein) and Private Henry Muldoon in Gallipoli (guess who), but also more recent moments of conflict: the word “redacted” crops up, as does the name Jean Charles de Menezes. As John Agard puts it in “Bandages” (channelling Shylock?): “how alike all people bleed”.

November 2, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the History editor

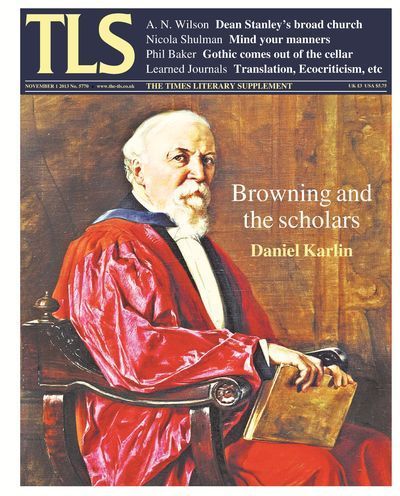

Robert Browning, as Daniel Karlin reminds us this week, was sensitive to

criticism, and even more sensitive to criticism of his wife. So when he read

a callous remark in Edward FitzGerald’s posthumously published

correspondence, he was moved to retaliatory verse. The sonnet he dashed off

to the Athenaeum is printed in the final volume of the Ohio/Baylor

edition of Browning’s works, though much of the back story is missing from

the editorial matter. The question of editors’ obligations to the authors

they take on is always a complex one, and never more so, Karlin argues, than

in Browning’s case. Browning’s own attitude to scholars who tried to study

his work prompts Karlin’s melancholy reflection that “the activity on which

I have spent a good part of my career is one which I have every reason to

believe the poet thinks impertinent, stupid and (to use his own words)

‘absolutely contemptible’”.

Arthur Conan Doyle, like Browning, was widowed, but his wife’s death was one

among several (or millions, if you include those in the First World War)

that touched the writer and fostered his interest in spiritualism. Reviewing

a new work on Conan Doyle, Jonathan Barnes is taken with the suggestion that

he arrived at spiritualism “along the path of science”, convincing himself

(as later with the existence of fairies) that life after death was “simply

there”.

Donna Tartt has an unusually slow rate of production for a contemporary

novelist. Alex Clark reviews her third novel in as many decades, The

Goldfinch, a characteristically ambitious exploration of a young man’s

reaction to the violent death of his mother, which Clark finds “impressively

mysterious . . . a pretend picaresque that refuses to stay on track”.

These gloomy topics might seem appropriate for the time of year when

Christians observe the “days of the dead”, and Western children dress up to

demand sweeties with menaces. Phil Baker sees in an Encyclopedia of the

Gothic the spread of such concerns beyond the confines of “genre”

literature or seasonal observance. Gothic, he writes, has “climbed out of

the cellar”. It is now “a way of life”.

David Horspool

November 1, 2013

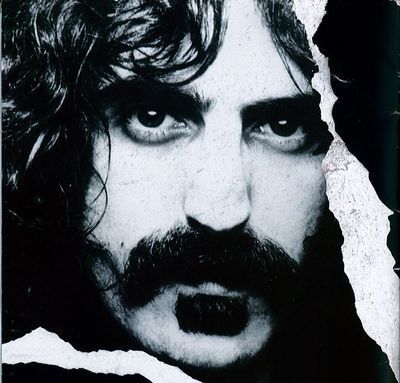

‘200 Motels’

Frank Zappa, 1970 © Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Frank Zappa finally

got his posthumous revenge. Forty-two years after his sold-out 200 Motels concert was cancelled at the

Royal Albert Hall on grounds of obscenity (“filth for filth’s sake” in the

words of the RAH’s general manager at the time Frank Mundy), the piece had its

UK premiere this week in the Royal Festival Hall; among its memorable lines, delivered in a mock-pitying tone: “Lord,

have mercy on the people in England for the terrible food these people must eat”

(this was the 70s, remember).

The show was part

of the year-long The Rest is Noise festival of 20th-century music at

the Southbank, inspired by Alex Ross’s book of that title. We were told that

there were some in the audience who’d had tickets for the original performance

(and there certainly were one or two Frank Zappa lookalikes in evidence). There

is a film 200 Motels, which is

apparently almost unwatchable but, according to Zappa (who died in 1993 aged

52), “For the audience that already knows and appreciates [his band] The

Mothers of Invention, 200 Motels will

provide a logical extension of our concerts and recordings . . . . For those

that can’t stand The Mothers and have always felt we were nothing more than a

bunch of tone-deaf perverts, 200 Motels

will probably confirm their worst suspicions”.

It’s certainly a weird and wonderful

piece, satirically scathing and characteristically scatological. I can see that

it might have caused offence in the early 70s, but today it’s more funny than

anything and at times childishly zany (it’s not always possible to buy the

whole Zappa package). The 200 motels were visited by Zappa and his band on one

tour in the 1960s, and the piece is in part a cry of boredom provoked by life

on the road (it’s set in the town of Centerville). The first two soloists,

Frank and Mark, have the appearance of bozo roadies; they are later joined by a

totally unprepared journalist (a superb performance by the soprano Claron

McFadden) who has come to interview a scornful Zappa. Tony Guilfoyle does a

passable impersonation as Frank (below), while the musician’s daughter Diva Zappa

seductively filled the role of Groupie 2, along with Groupie 1 Sophia Brous.

And, something of a surprise, Jay Rayner, better known as a food writer and

broadcaster, appears, winningly, as the bass Bad Conscience (Rayner looks like

he could have slotted seamlessly into The Mothers of Invention).

© Chris Christodoulou

Not forgetting the full forces of the

BBC Concert Orchestra and Southbank Sinfonia, under the appropriately

enthusiastic baton of Jurjen Hempel, the London Voices and a 7-piece rock

band. What the audience got for this one-off performance in the presence

of the artist’s widow Gail Zappa was 90 minutes of dissonant, occasionally sublime

and occasionally plain overblown music. Close your eyes at times and you could

almost believe you were listening to Schoenberg at his most lushly

orchestrated; Edgard Varèse has also been invoked (according to Gail Zappa, her husband “always

loved . . . Varèse and Stravinsky”). Writing in the programme note, the

singer-songwriter Alan Clayson talks of how the work “highlights its creator’s

pre-eminence in breaching the abyss between highbrow and lowbrow, pop and

‘classical’, ‘real’ singing and rock’n’roll hollering. Finally, “it will

reinforce” Zappa’s position “as the most remarkable North American composer of

the twentieth century and perhaps any other time”. Wow! Certainly one of the

most inventive – not for nothing was his band called The Mothers of Invention.

Finally, in a week

that was marked by the news of the death of Lou Reed, it’s worth being reminded

of the fact that when Zappa was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll

Hall of Fame in 1995, the eloquent and rather beautiful tribute was given by .

. . Lou Reed. It’s worth hearing. Two great, but very different, musicians.

And at this point, can I suggest that Lou Reed’s Rock n Roll Animal (recorded in 1973 in New York) is simply the

best live rock and roll album of all? It’s hard not to love the camp-ironic way

in which Reed delivers the lines “I wish that / I was born a thousand years

ago. / I wish that / I’d sailed the darkened seas / on a great big clipper

ship, going from this land here to that. / I’d put on a sailor’s suit and cap .

. .”.

Not far behind it

on my list would be an album of live recordings made over a period of 20 years

(1968–88) and at many different venues (200 motels . . . ): the intermittently

brilliant You Can’t Do That on Stage

Anymore, by Frank Zappa.

October 30, 2013

Not the hundred best novels?

By MICHAEL CAINES

Is it true, as Samuel Johnson declared, that nothing "odd", in literary terms, will last? As mentioned a while ago, for a certain well-placed critic, writing in 1898, that odd book Tristram Shandy could not be considered among the hundred best novels ever written. Now here's what he actually thought were the best.

Sometime editor of the Illustrated London News, an authority on the Brontës and Napoleon, Clement K. Shorter was in the middle of a flourishing career when this list appeared in the monthly journal called The Bookman. He doesn't explain what exactly makes a book one of the "best", only that he has deliberately limited himself to one novel per novelist. Living authors are excluded – although he cannot resist adding a rider of eight works by "writers whose reputations are too well established for their juniors to feel towards them any sentiments other than those of reverence and regard". In fact, I'd say if he'd been trying to prophesy what would still be regarded as a classic a century later, Shorter's shorter list is more proportionally successful than his longer one.

As intended, Shorter's list might still serve as an "actual incentive" to discovery, as he hoped, for "the youthful student of literature" (one to put next to David Bowie's, maybe) at least partly because of what seem now to be its many oddities. People have become less hesitant, for example, before praising the living (the more junior the better) and, one suspects, less willing to praise P. G. Hamerton's Marmorne. I'm not sure Bracebridge Hall is even in print on this side of the Atlantic. And would you have chosen Silas Marner over Middlemarch?

It's just a list, of course, and Shorter acknowledged that others could probably come up with "numerous omissions". It's curious to see what we might call classic or canonical novels among the works they've outlasted, though. Praise for, say, Jane Austen might have echoed down the centuries, but this doesn't mean that we share the same aesthetic values as readers who praised her in the early nineteenth or early twentieth centuries.

It's difficult to imagine any except the most foolhardy of readers reading every book on Shorter's list now, let alone agreeing with him. In John Sutherland's compendious Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction, however, may be found informed summary views of many of the lesser-known names below – see the parenthetical quotations for the ones that interested me.

For that full 1898 flavour, names and dates are as Shorter gives them.

1. Don Quixote - 1604 - Miguel de Cervantes

2. The Holy War - 1682 - John Bunyan

3. Gil Blas - 1715 - Alain René le Sage

4. Robinson Crusoe - 1719 - Daniel Defoe

5. Gulliver's Travels - 1726 - Jonathan Swift

6. Roderick Random - 1748 - Tobias Smollett

7. Clarissa - 1749 - Samuel Richardson

8. Tom Jones - 1749 - Henry Fielding

9. Candide - 1756 - Françoise de Voltaire

10. Rasselas - 1759 - Samuel Johnson

11. The Castle of Otranto - 1764 - Horace Walpole

12. The Vicar of Wakefield - 1766 - Oliver Goldsmith

13. The Old English Baron - 1777 - Clara Reeve

14. Evelina - 1778 - Fanny Burney

15. Vathek - 1787 - William Beckford

16. The Mysteries of Udolpho - 1794 - Ann Radcliffe

17. Caleb Williams - 1794 - William Godwin

18. The Wild Irish Girl - 1806 - Lady Morgan

19. Corinne - 1810 - Madame de Stael

20. The Scottish Chiefs - 1810 - Jane Porter

21. The Absentee - 1812 - Maria Edgeworth

22. Pride and Prejudice - 1813 - Jane Austen

23. Headlong Hall - 1816 - Thomas Love Peacock

24. Frankenstein - 1818 - Mary Shelley

25. Marriage - 1818 - Susan Ferrier

26. The Ayrshire Legatees - 1820 - John Galt

27. Valerius - 1821 - John Gibson Lockhart

28. Wilhelm Meister - 1821 - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

29. Kenilworth - 1821 - Sir Walter Scott

30. Bracebridge Hall - 1822 - Washington Irving

31. The Epicurean - 1822 - Thomas Moore

32. The Adventures of Hajji Baba - 1824 - James Morier ("usually reckoned his best")

33. The Betrothed - 1825 - Alessandro Manzoni

34. Lichtenstein - 1826 - Wilhelm Hauff

35. The Last of the Mohicans - 1826 - Fenimore Cooper

36. The Collegians - 1828 - Gerald Griffin

37. The Autobiography of Mansie Wauch - 1828 - David M. Moir

38. Richelieu - 1829 - G. P. R. James (the "first and best" novel by the "doyen of historical novelists")

39. Tom Cringle's Log - 1833 - Michael Scott

40. Mr. Midshipman Easy - 1834 - Frederick Marryat

41. Le Père Goriot - 1835 - Honoré de Balzac

42. Rory O'More - 1836 - Samuel Lover (another first novel, inspired by one of the author's own ballads)

43. Jack Brag - 1837 - Theodore Hook

44. Fardorougha the Miser - 1839 - William Carleton ("a grim study of avarice and Catholic family life. Critics consider it the author's finest achievement")

45. Valentine Vox - 1840 - Henry Cockton (yet another first novel)

46. Old St. Paul's - 1841 - Harrison Ainsworth

47. Ten Thousand a Year - 1841 - Samuel Warren ("immensely successful")

48. Susan Hopley - 1841 - Catherine Crowe ("the story of a resourceful servant who solves a mysterious crime")

49. Charles O'Malley - 1841 - Charles Lever

50. The Last of the Barons - 1843 - Bulwer Lytton

51. Consuelo - 1844 - George Sand

52. Amy Herbert - 1844 - Elizabeth Sewell

53. Adventures of Mr. Ledbury - 1844 - Elizabeth Sewell

54. Sybil - 1845 - Lord Beaconsfield (a. k. a. Benjamin Disraeli)

55. The Three Musketeers - 1845 - Alexandre Dumas

56. The Wandering Jew - 1845 - Eugène Sue

57. Emilia Wyndham - 1846 - Anne Marsh

58. The Romance of War - 1846 - James Grant ("the narrative of the 92nd Highlanders' contribution from the Peninsular campaign to Waterloo")

59. Vanity Fair - 1847 - W. M. Thackeray

60. Jane Eyre - 1847 - Charlotte Brontë

61. Wuthering Heights - 1847 - Emily Brontë

62. The Vale of Cedars - 1848 - Grace Aguilar

63. David Copperfield - 1849 - Charles Dickens

64. The Maiden and Married Life of Mary Powell - 1850 - Anne Manning ("written in a pastiche seventeenth-century style and printed with the old-fashioned typography and page layout for which there was a vogue at the period . . .")

65. The Scarlet Letter - 1850 - Nathaniel Hawthorne

66. Frank Fairleigh - 1850 - Francis Smedley ("Smedley specialised in fiction that is hearty and active, with a strong line in boisterous college escapades and adventurous esquestrian exploits")

67. Uncle Tom's Cabin - 1851 - H. B. Stowe

68. The Wide Wide World - 1851 - Susan Warner (Elizabeth Wetherell)

69. Nathalie - 1851 - Julia Kavanagh

70. Ruth - 1853 - Elizabeth Gaskell

71. The Lamplighter - 1854 - Maria Susanna Cummins

72. Dr. Antonio - 1855 - Giovanni Ruffini

73. Westward Ho! - 1855 - Charles Kingsley

74. Debit and Credit (Soll und Haben) - 1855 - Gustav Freytag

75. Tom Brown's School-Days - 1856 - Thomas Hughes

76. Barchester Towers - 1857 - Anthony Trollope

77. John Halifax, Gentleman - 1857 - Dinah Mulock (a. k. a. Dinah Craik; "the best-known Victorian fable of Smilesian self-improvement")

78. Ekkehard - 1857 - Viktor von Scheffel

79. Elsie Venner - 1859 - O. W. Holmes

80. The Woman in White - 1860 - Wilkie Collins

81. The Cloister and the Hearth - 1861 - Charles Reade

82. Ravenshoe - 1861 - Henry Kingsley ("There is much confusion in the plot to do with changelings and frustrated inheritance" in this successful novel by Charles Kingsley's younger brother, the "black sheep" of a "highly respectable" family)

83. Fathers and Sons - 1861 - Ivan Turgenieff

84. Silas Marner - 1861 - George Eliot

85. Les Misérables - 1862 - Victor Hugo

86. Salammbô - 1862 - Gustave Flaubert

87. Salem Chapel - 1862 - Margaret Oliphant

88. The Channings - 1862 - Ellen Wood (a. k. a. Mrs Henry Wood)

89. Lost and Saved - 1863 - The Hon. Mrs. Norton

90. The Schönberg-Cotta Family - 1863 - Elizabeth Charles

91. Uncle Silas - 1864 - Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

92. Barbara's History - 1864 - Amelia B. Edwards ("Confusingly for bibliographers, she was related to Matilda Betham-Edwards and possibly to Annie Edward(e)s . . .")

93. Sweet Anne Page - 1868 - Mortimer Collins

94. Crime and Punishment - 1868 - Feodor Dostoieffsky

95. Fromont Junior - 1874 - Alphonse Daudet

96. Marmorne - 1877 - P. G. Hamerton ("written under the pseudonym Adolphus Segrave")

97. Black but Comely - 1879 - G. J. Whyte-Melville

98. The Master of Ballantrae - 1889 - R. L. Stevenson

99. Reuben Sachs - 1889 - Amy Levy

100. News from Nowhere - 1891 - William Morris

And those lucky living eight:

An Egyptian Princess - 1864 - Georg Ebers

Rhoda Fleming - 1865 - George Meredith

Lorna Doone - 1869 - R. D. Blackmore

Anna Karenina - 1875 - Count Leo Tolstoi

The Return of the Native - 1878 - Thomas Hardy

Daisy Miller - 1878 - Henry James

Mark Rutherford - 1881 - W. Hale White

Le Rêve - 1889 - Emile Zola

October 25, 2013

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

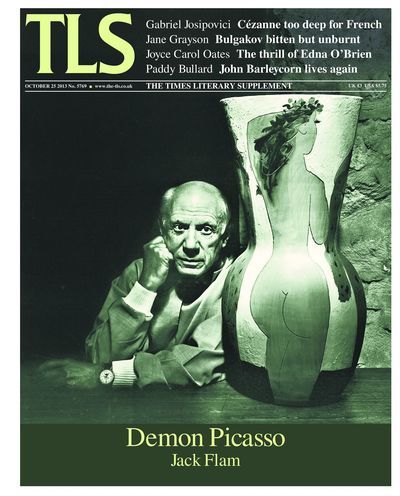

For much of his life and ever since his death, Picasso has been universally

accepted as one of the greatest artists ever known. But his works of the

1920s and 30s still sometimes met with puzzlement or hostility – Carl Jung,

for example, called him an “underworld” personality who followed “the

demoniacal attraction of ugliness and evil”. It is just these “pathological”

aspects of Picasso’s vision that interest T. J. Clark in his new study –

“ambitious but exasperating”, according

to our reviewer Jack Flam – of the artist who sought “something similar

to what Nietzsche characterized as Untruth: a post-moral, post-Christian

confrontation with reality in all its monstrous, unfiltered forms”. From a

new edition of Paul Cézanne’s letters, Gabriel Josipovici forms a very

different picture, “a group of happy, highly educated friends, steeped in

Virgil and Horace, enjoying a life of long hikes, picnics and swims in the

rivers”: hardly the Cézanne of popular legend, a solitary seeker after

truth, sacrificing all for his art – though such qualifications are lost “on

a public hungry for modern saints now the religious variety has gone for

good”.

Ireland, Yeats’s land of plaster saints, becomes “a land of shame, a land of

murder and a land of strange sacrificial women” in the stories of Edna

O’Brien. Joyce

Carol Oates enjoys the passion, lyricism and humour with which O’Brien

animates a world of “emotional extravagance and emotional starvation”. The

American poet James Dickey was no stranger to emotional extravagance, as

recorded by Jules Smith who reviews Dickey’s 960-page Complete Poems,

in which among much else “Despair and exultation / Lie down together and

thrash / In the hot grass”. Dickey’s editor considers that he was

“transformed into a poet by World War II”. Some of his compatriots were

transformed into conservationists: the “monuments men” who were charged with

rescuing the incomparable artistic heritage of an Italy under bombardment.

John Foot reviews a second instalment of their story, soon to be a major

motion picture.

Alan Jenkins

October 24, 2013

‘The Last Hundred Days’

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Is it ok to big up a TLS contributor on this site? If

so, here goes. Patrick McGuinness’s first novel, with the Napoleonic title The Last Hundred Days has

recently been published in France (as Les Cent Derniers Jours), and

been shortlisted for three prizes (the British edition, published by Seren,

was shortlisted for the Booker in 2011). Sean O'Brien praised it in the TLS, describing it as "both funny and horrifying".

When I read the novel (before it was shortlisted for the

Booker, I hasten to add) I was knocked out by it. It is set in Bucharest in

1989, in the months before the fall of Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu (somehow husband and wife seem inextricably

linked, and they suffered the same grim fate of course). The story is told by a

young English lecturer who has accidentally landed a job at the university and

is pitched into a world of absurdity, surveillance, corruption and police

brutality.

The narrator reflects on his new home: “The Paris of the East . . . it was an epithet I’d heard before.

Second-string cities are always described as the somewhere of somewhere else” –

how true that sounds.

McGuinness describes the sheer boredom – “Totalitarian boredom . . . is a state of expectation already heavy with

its own disappointment, the event and its anticipation braided together in a

continuous loop of tension and anti-climax” – and misery of living in a totalitarian state, where people queue for

food “in sub-zero temperatures or unbearable heat . . . . No one knew how much

there was of anything. Often you didn’t even know what there was.

You could queue for four hours only for everything to run out just as you

reached the counter”.

As regular readers of the TLS will know, McGuinness is a

French specialist based in Oxford, with a particular interest in francophone

Belgian literature (he has written a monograph on Maurice Maeterlinck). His

most recent collection of poems Jilted

City (Carcanet, 2010) contains an attractive sequence of poems, “Blue

Guide”, on Belgian railway stations, culminating in the rather Proustian

“Stations where the train doesn’t stop”: “Etterbeek, la Hulpe. Epinal,

Rixensart, Profondsart, . .”.

Jilted City closes with a section of

translations from the fictional Romanian poet Liviu Campanu (1932–94), “a poet and university lecturer

from Bucharest who fell out of favour with the Ceaușescu regime” and was sent to Constanța on the Black Sea (formerly the Tomis of Ovid’s

exile), his “letters from Bucharest, still wet / from being steamed open”.

Campanu appears in the novel, a victim of repressive bureaucracy, as does another

poet in exile in Constanța who has come to Bucharest for the

street protests: “I recognised Andrei Liviu the poet, deathly pale but walking

steadily”.

The absurdities multiply: Elena Ceaușescu who, in spite

of leaving school at 14, gained a PhD in Chemistry from the University of

Bucharest, is “Comrade Academician Professor” and heads the unlikely-sounding

Romanian Cosmic Research Centre. One of the most memorable scenes in the book

has Slobodan Milosevic, on a state visit to Romania, looking on in contempt at

the drunken antics of the Ceaușescus’ playboy son

Nicu in a Bucharest nightclub, forcing himself on young women to a beat of

“pogrom rock”.

McGuinness had the good fortune, or misfortune, to be in Bucharest in 1989.

In an interview with Florence Noiville in Le

Monde des livres last Friday, he reveals that “there was nothing to do”

there. As a consequence he set about taking everything in. Noiville points to

the “dreamlike” dimension of this “strange and poetic novel”; it is both

those things, and extremely well written: a page-turner (although we

know what’s coming) as well as a profound meditation on truth and moral

compromise.

October 22, 2013

Fifty years of the National Theatre, after a century of disagreement

By MICHAEL CAINES

Not fifty but forty-eight years ago, an anonymous theatre critic (Irving Wardle) could write in the TLS: ". . . we have begun to take for granted the existence of such unprecedented developments as the Aldwych [where the RSC was then based] and the National Theatre as if they had been there for generations"; he could also refer to the "inestimable importance" of these subsidized cultural institutions, even if, at the time, he felt that new writers were better served by their commercial counterparts.

Such statements might not seem controversial now, but the debate over whether or not a national, subsidized theatre was needed had been going on for a century when Wardle, a former TLS staff member, wrote those words. "The enormous number of Englishmen who do not care for the play, and never go to it, would hardly like to be taxed for theatrical purposes", Herbert Paul wrote in his 1902 book on Matthew Arnold. "As though there were the remotest likelihood of English theatrical history repeating French theatrical history two centuries and a quarter behind time!", A. B. Walkley wrote in the TLS in the same year, with the example of the Comédie Française in mind (although his main point, to be fair, was not that he didn't want a national theatre, only that its proponents hadn't proved that the public wanted a national theatre).

Comments like this are not difficult to find in the years before the National Theatre, under the directorship of Laurence Olivier, gave its first performance, on October 22, 1963, with Hamlet starring Peter O'Toole. I wrote in the TLS, back in 2004, about Samuel Phelps, the nineteenth-century Shakespearean actor and manager of the Sadler's Wells Theatre, who hoped the government would see from his example that it might be possible to establish a national theatre "upon a moderate scale of expense".

His was not a lone voice, but the government wasn't interested, despite some persistent problems: "the sordid speculations of monopolist lessees and the injurious restrictions of foolish Lord Chamberlains", as the London and Westminster Review had put it in 1837. The Lord Chamberlain's Office still had the power to censor stage plays in Britain when the National opened for business, as it had done since 1737, and as it would do for another five years.

Yet here we are – 800 productions later, apparently – with the National about to enter a new era under the leadership of Rufus Norris (who, it is rumoured, once gave extremely good drama lessons to a current member of the TLS staff), the doubts, it would seem, long put to rest. The model of producing, say, War Horse in the West End and a series of smaller shows in the Shed or the Cottesloe (currently closed and due to reopen next year under the new name, unfortunately, of the Dorfman Theatre; what was wrong with the old one?) vindicates the idea of a national theatre as conceived by Harley Granville-Barker many years ago.

Granville-Barker's vision was of one large and one small theatre on the south bank of the Thames, with workshops, rehearsal rooms, restaurants – a "great factory", as the TLS saw it, "where drama is made before it is sold". Substantial public funding would go into producting about fifty plays a year (OK, so that's not quite what's happened, generally speaking) and paying for a company of about 100 actors. For him, "there is no othe way in which the National Theatre can be made to proclaim that the drama is worthy of, so to speak, its cathedral". And now, of course, there is National Theatre Live to extend the cathedral into "a cinema near you".

Evidently, despite the philistinism for which the English are well renowned, better things are just about possible. Even if they do have to be debated for a hundred years beforehand.

© Simon Annand

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers