Peter Stothard's Blog, page 47

February 14, 2014

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

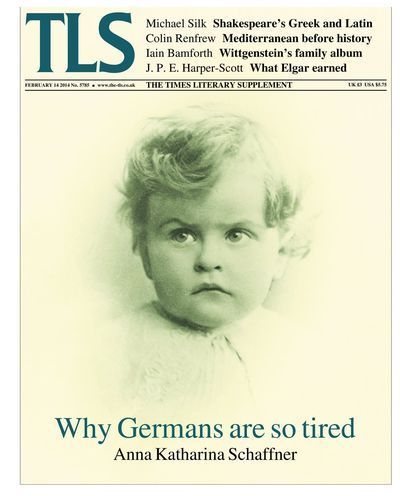

The baby Ludwig Wittgenstein on this week’s cover comes from what Iain Bamforth describes as a “compelling” visual and textual biography of a philosopher who himself described his work as “really only an album”. Michael Nedo’s “judiciously edited” book uses postcards and patents to show “the first evidence of the interest in technical objects that was a constant in Wittgenstein’s life” – and a collage of “family resemblances”, ostensibly scientific but also “oddly mystical”.

While an Austrian was transforming philosophy at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Germans were exhausting themselves in ways that are the subject of Anna Katharina Schaffner’s review of two books linking individual illness with the state of society. Nudism, muesli and yoga were all innovative responses to national tiredeness at the time, and some are still called upon during the current German obsession with “overwork”. Being “burned out” in Germany today, Schaffner says, is “socially acceptable”, “implying, as it does, that one has simply worked too hard”.

Michael Silk considers the tension between the Germanic and Latin influences on the language of Shakespeare, reviewing Colin Burrow’s book Shakespeare and Classical Antiquity. Readings of England’s greatest writer as Germany’s Gothic genius are not as fashionable as they were in the Romantic era of Schlegel, but Silk wonders if the Latinity is not now stressed too much: “we do well to ponder, not how much Shakespeare classicizes, but how relatively little”.

A. N. Wilson notes the gallantry of Hugh Trevor-Roper in taking “more than his share of the blame” for the fiasco of the fake “Hitler Diaries”. Geordie Torr explains how Wagner came to supply the names for newly discovered frogs in Papua New Guinea, Gudrun and Brünnhilde being merely two of them. Arnold Hunt praises an account of early modern Protestantism which “vividly and movingly” rebuts the notion of “deep spiritual isolation” promoted by Weber.

Peter Stothard

February 13, 2014

‘Translation as Art’

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The battle of the canapés was keenly fought. Representing France were the pissaladières, Germany called on its dumpling balls, the Low Countries wheeled out their puff pastries and the Spanish deployed tortillas. Europe House, the headquarters of the EU in the UK, yesterday evening hosted the annual Society of Authors translation prize presentations (co-sponsored by the TLS). In a spirit of open borders, the Hebrew translation prize and the Arabic prize were also represented (pickled cucumbers and honey pastries respectively, all delicious).

The translators’ readings were excellent: William Maynard Hutchins from the Yemeni novelist Wajdi al-Ahdal’s brutal novella A Land Without Jasmine, followed by Jonathan Wright and his version of Youssef Ziedan’s Azazeel which, Wright pointed out, was rare in being a novel in Arabic without any Arabs in it (it’s set in the fifth century).

Poetry was eloquently present in Ian Crockatt’s versions of Rilke and Beverley Bie Brahic’s beautiful rendition of Apollinaire. Frank Wynne was eloquent in his reading from the Peruvian novelist Alonso Cueto’s The Blue Hour while, in a starkly different tone, David Colmer raised laughs with his extract from Dimitri Verhulst’s visceral, brilliant novel The Misfortunates (set in Belgium rather than Holland), with its appropriate broken Lager bottle – Stella Artois? – on the cover. Todd Hasak-Lowy meanwhile injected existential anguish with his reading from the Israeli novelist Asaf Schurr’s Motti (although as Lowy points out in his Translator’s Afterword, while “People read Hebrew writers primarily to get The Story. The big one. The national one”, politics and history are entirely absent from Motti).

Translators travel: Maynard Hutchins from South Carolina, while Hasak-Lowy thanked the organizers for “getting him out of Chicago in February”.

This was followed by a conversation between Adam Mars-Jones and Dr Ian Patterson. I had assumed that Patterson would be interviewing Mars-Jones but it turned out to be the other way round. Patterson (Cambridge) is the translator of the final volume of Proust’s novel Le Temps retrouvé in the Penguin Millennium edition (each volume was assigned to a different translator), a volume he opted to entitle Finding Time Again (. . . to walk the dog?). Patterson revealed that he had been so pleased with his version of one passage that he broke the translator’s rule and looked up existing versions only to discover that his translation exactly replicated those versions! What, you might wonder, is a translator to do in that situation?

This is the sixth time I’ve reported for the TLS on the translation prizes. There has been a good deal of poetry: Luciano Erba, Paul Celan, Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis, Valerio Magrelli, Luis de Góngora, Quevedo, Valérie Rouzeau and Cavafy, and plenty of excellent novels: from Frédéric Beigbeder, Laurent Quintreau, Hans Keilson, António Lobo Antunes and Giovanni Arpino among others.

I was particularly pleased to be directed to George Seferis’s Levant Journal and fascinated to read Ron Leshem’s novel of Israeli army life Beaufort. The first translation (by Malcolm Imrie) of Gabriel Chevallier’s great Great War novel Fear was rightly celebrated last year, while a particularly welcome discovery for me was Thomas Pletzinger’s compelling Funeral For a Dog (for which Ross Benjamin was runner-up last year with his translation from German).

Striking to me is the number of translators who can operate in more than one language: multiple winner Frank Wynne can range from Houellebecq and Beigbeder to the excellent Argentinian novelist Marcelo Figueras and, this year, Alonso Cueto. Margaret Jull Costa covers both Spanish (Bernardo Atxaga and others) and Portuguese (Antunes and Eça de Queiroz), as does Peter Bush (Juan Goytisolo and Miguel Sousa Tavares). Anthea Bell does Asterix and Stefan Zweig while, by my reckoning Shaun Whiteside can do three languages (French, German and Italian). Other, highly accomplished, translators restrict themselves to one language: Susan Wicks, Michael Hofmann, Jamie McKendrick, Beverley Bie Brahic and Roderick Beaton.

Pre-eminent among the single-language translators was the French specialist Barbara Wright (below, 1950s), to whom a volume was recently dedicated: Barbara Wright: Translation as art, edited by Madeleine Renouard and Debra Kelly (Dalkey Archive Press). According to the editors Wright, who died in 2009, “could have become a brilliant pianist". Among the authors whose work she translated were Raymond Queneau, the nouveaux romanciers Alain Robbe-Grillet, Robert Pinget, Marguerite Duras and Nathalie Sarraute, Michel Tournier, Patrick Modiano and Jean Rouaud. She was appointed Officier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1986 “for services to the French, language, literature and culture” and promoted to Commandeur in 2002.

She was also a clear-eyed reviewer for the TLS for many years, a pricker of pomposity, even if at times she could leave the reader bemused: of Michel Tournier’s wonderful collection of stories Le Coq de bruyère (1978) she concluded “M Tournier has a wide range of subjects, and of course he writes extremely well – but he still frightens me” (!)

Pinget perhaps provided the stiffest translating challenge for her (although Queneau’s Exercices de style would have run him close). How, for instance, does one render “Arrivée à la carrière la vieille posait son pliant dans l’herbe et se mettait à son tricot pendant que son bétail bêlant et bringueballant batifolait dans la betterave, . . . “ (from Passacaille, 1969)?

In Recurrent Melody (her loose title translation, 1975) Wright goes for: “When she got to the quarry the old woman put the folding stool down on the grass and got on with her knitting while her bleating beasts were bouncing about in the beetroot, . . .” OK, so she omitted “bringueballant”, “shaking” or “swaying”, which is a shame/a bit naughty, but it’s a plain, unadorned and effective translation. John Sturrock wrote of it in the New York Times Book Review in 1979: “Barbara Wright’s translation has matched Mr. Pinget’s French with wit and skill; she has kept the sense throughout and found the right equivalent sounds”.

Pinget’s advice to his English translator was “Don’t bother too much about logic: everything in Passacaille is directed against it”.

February 12, 2014

Questioning the Stoner phenomenon

By RUPERT SHORTT

The praise is ecstatic. According to the New York Times, John Williams’s Stoner “is a perfect novel, so well told and beautifully written, so deeply moving, that it takes your breath away”. Similar verdicts – along with the equally breathless claim that Stoner’s colossal virtues have been strangely overlooked – are rampant in Britain. The chorus is not unanimous, of course. Internet humbug-monitors prompt me to raise a couple of cheers for digital democracy. But cooler assessments of the novel have been in short supply.

The protagonist, William Stoner, comes from a poor farming background in central Missouri. Sent away to study agriculture at college just before the First World War, he shifts his focus to literature, knuckles down, and duly becomes a professor. I am not spoiling things by saying that he weds the wrong woman: that much is revealed on the book’s cover. The rest of the story charts the decay of the marriage and of Stoner’s professional life, among other episodes. At his best, Williams contrives to tell the tale with insight and pathos.

These and other strengths are hailed by John McGahern in his Introduction, but the novel’s merits are no cover for major flaws. I am only giving away a small amount when I add that Stoner’s wife Edith is bad as well as mad. She oppresses her husband with no trace of guilt for forty tragic years. We are nevertheless required to believe not only that he would do virtually nothing to defend himself, but also that Edith’s unspeakable malignity towards Stoner is matched by one of his colleagues. Again, however, the target of all the fury offers virtually no resistance. The other benign characters tend to be equally supine. This all comes to pass because the naturalistic framework is not what it seems. When Edith’s fourth-formish nihilism is echoed in commentary by the omniscient author, our suspicions about puppets and string-pulling start to look incontrovertible.

Another fault passed over by the hyper-ventilators is stylistic. Williams’s prose is frequently well crafted. But it can also be sloppy – sentence after undifferentiated sentence consists of two long clauses linked by an “and” – and sodden in clichés such as “rolling hills”. The author’s inattention sometimes makes him a poor observer of his own characters. At one point, for example, we are told that Edith is obsessed with housework; then, a short time later, that in an apparent break with habit, “she even made a few movements toward caring for the house”. Williams has a sharp ear for dialogue: Stoner is nothing if not uneven. But he still shows too little and tells too much.

Julian Barnes, one of the novel’s foremost English fans, has acclaimed it as a work of “echoing sadness”. John McGahern is willing to concede that the gloom is “remorseless”. Yet in an interview given shortly before his death in 1994, Williams himself declared that Bill Stoner had had a “very good life”. That a work of art feeds multiple interpretations can clearly be proof of quality. Sometimes, though, it is a mark of muddle and no more.

February 11, 2014

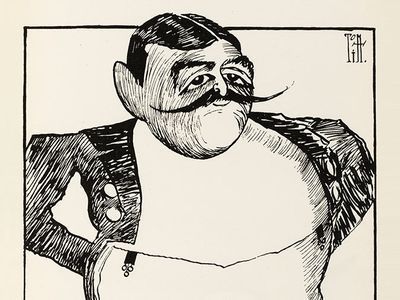

Should Buchan's villain receive an apology at the Proms?

Sir Edgar Speyer by Tom Titt (1913) Photograph: (c) Mary Evans Picture Library 2010

By MICHAEL CAINES

By which question I mean: consider the "troublesome case of Sir Edgar Speyer".

Born in New York and educated in Germany, Speyer was a financier who became a British citizen in 1892; he went on to become a baronet, a privy councillor and, among other things, the saviour of the Proms, "placing them on a sound financial footing when they were threatened with bankruptcy", as Mark Bostridge puts it in this review of a new book about Speyer by Anthony Lentin, from the current issue of the TLS.

Speyer was also, however, a notable victim of the anti-German prejudice that had been building up for many years before the outbreak of the First World War, with the rumours about his links to Germany, as well as public displays of hostility against him and his wife, eventually driving him to emigrate, to the United States, in 1915. It's an extraordinary piece of pyrrhic scapegoating, even if Speyer was, as his latest biographer suggests, guilty of putting business before loyalty to his adopted country.

The same year, 1915, saw the publication of John Buchan's great "shocker" The Thirty-Nine Steps, in which the archvillain is apparently based on Speyer (see the end of Leanne Langley's fine account of this "saviour in London cultural history"). Readers of the time might well have seen a resemblance.

After many hair-breadth 'scapes, Buchan's hero Richard Hannay tracks down his enemies, a trio of German spies, to their lair: a villa on the Kentish coast called Trafalgar Lodge. (Speyer's house on the Norfolk coast became a particular focus of speculation.) Outside is an enormous Union Jack. Only by a lucky stroke does Hannay see through these and other intimations of respectability and fervid patriotism to see the leader of the gang for what he is: "sheer brain, icy, cool, calculating, as ruthless as a steam hammer. . . . His jaw was like chilled steel, and his eyes had the inhuman luminosity of a bird's". Continuing the bird analogy to the end, Hannay sees a "white fanatic heat" in those eyes; "Appleton" is a patriot, after all. Just the wrong sort of patriot.

The book was a bestseller, and not by accident. As Christopher Harvie noted in his Oxford edition (1993), Buchan had read The Riddle of the Sands by Esrkine Childers, in which another nefarious German plot is foiled, and in 1914 checked "what its sales had been". Like Childers's yarn, The Thirty-Nine Steps played perfectly on the mood of the times. The TLS reviewer, Harold Hannyngton Child, probably wasn't alone in admiring Buchan's ability to make the wartime reader feel as if "he himself was the hero": "we are heartily grateful to Mr. Buchan for giving the world so vivid and truthful a narrative of our adventures, escapes, and achievements".

That climactic confrontation with Appleton and his cronies is a good example of Buchan's art as Child describes it, as the outcome hangs on "our" (ie, Hannay's) vivid impressions of his opponents and the tipping of the scales one way and then the other. I wonder, though, if the credibility of the story would have also depended on the widespread knowledge of the British Establishment being infiltrated at the highest levels – as in the recent case of Sir Edgar Speyer, "spy".

Buchan's brilliance as a storyteller clashes with the likely truth of the matter, that Speyer "was probably neither anti-British nor anti-German", just driven by his business concerns. An unlikely fanatic, then – and, in other respects, an entirely admirable supporter of the arts, not least the Proms and the Whitechapel Art Gallery. It doesn't always happen that author and reviewer find themselves in perfect agreement, so savour this moment while you can: Mark Bostridge echoes Anthony Lentin in arguing that this centenary year presents a good time for "some belated recognition" of Speyer's philanthropy, "not least his efforts in saving the Proms from extinction". How about "a gesture of homage at some point during this year's last night"?

February 7, 2014

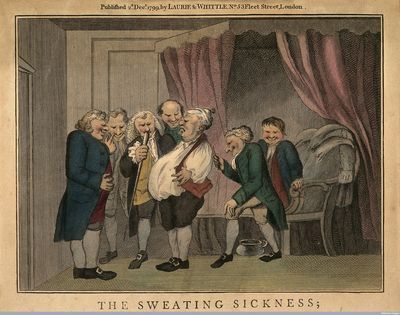

False friends

Tom Ruby being tricked by six friends into thinking he is suffering from the "sweating sickness", thereby missing his feast. Coloured line engraving, 1799, after John Nixon? (Wellcome Library)

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's no surprise that the discovery of that fine TLA "OMG" in a letter addressed to Winston Churchill has caught people's interest – or that there are more such amusing occurrences of modern coinages in olden times to be found. (E.g. "Face-book" in a newspaper from 1902.) Unusual words and seemingly anachronistic terms will always catch a reader's eye. An old favourite of mine is a latter-day cliché turning up in 1623, in a play by John Webster called The Devil's Law-case, which has a lawyer in court wheel round at the end of his cross-examination of a witness and say, Columbo-style, "One question more and I have done . . .". When the reply to the question is "Never", he adds, anticipating a technique for the stressing of key plot points in TV legal dramas, centuries later: "Are you certaine of that?"

Less eye-catching but more common are what French teachers might call faux amis – false cognates that tempt the unsuspecting student into thinking French is really English in disguise. Yes, le weekend really is the weekend, but no, justesse is not justice and a gland is not a gland. And so on.

Such confusion can also come between other languages, between British and American speakers, and between present-day readers and the literature of the past. Chaucer provides many examples, though their context tends to alert the reader to be careful: "The sentence of the compleynt" in "The Complaint of Mars" refers to the thrust, the general point, not, say, its grammar; and 300 lines into "The Parliament of Fowls", a "stare" (starling) amid the "crane", the "lapwynge" and the "kyte", is perhaps unlikely to be misunderstood.

Things get trickier the later you go, in a different way. Robinson Crusoe might seem to be comprehensible, plain sailing, but according to my Penguin edition, "affectionately" apparently means "with great feeling". That doesn't sound so very far removed from the modern meaning, but when, in the Further Adventures, the question is asked: "Are you willing to go?", it must be in the obsolete sense of the word that Defoe has the reply come back "very affectionately": "No . . . I am far from willing . . .".

Or consider the example of James Boswell, describing himself as "dull" in 1763 – he's accusing himself of lacking vivacity, I think, rather than interest.

Or of Emma Woodhouse, who comes to feel "all the honest pride and complacency [contentment, according to Bharat Tandon's edition of the novel] which her alliance with the present and future proprietor [of Donwell Abbey] could fairly warrant". Our view of Emma Woodhouse might be a little unfair on her if we thought she was admitting here that the prospect of marrying into the Knightley family simply left her feeling smug.

The list could go on. Generous, rude, keep, gay, queer, dull, forecast, happy: the game is the opposite of tracing "OMG" back through time; instead, it could be to see how late some now-outmoded usage persists, without cheating, of course, and raiding the OED first (or the HTOED second), just through an in-the-course-of-things reading of some relatively well-known novels, as well as the odd lesser-known work. Apart from anything else, they serve as a reminder that language and literary taste have subtler shifts than merely disposing of, or bringing into play, the flashy inventions.

No doubt the full lexicographical, etymological account of the phenomenon already exists; but that's beside the point. You only need to be a reader of Jane Austen (or Dickens or George Eliot) to experience it for yourself – not least in the potentially somewhat confusing jolt of discovering that one's father-in-law, in the nineteenth century, might actually turn out to be one's stepfather. OMG, indeed.

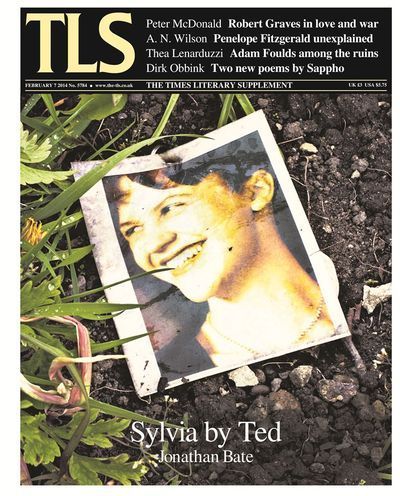

February 6, 2014

In this week’s TLS – a note from the Deputy Editor

Almost since the day Sylvia Plath committed suicide, she has been cast by some as a helpless victim of Ted Hughes. Biographies published last year (the fiftieth anniversary of her death) suggest that this “fantasia” is losing its hold, and interest has shifted to her life before she met her husband; while the story of his coming to terms with his loss is only slowly emerging. Jonathan Bate, Hughes’s biographer, draws on Hughes’s diary and the drafts of a projected long poem – combining Beethoven and Wordsworth in a “lifeline music . . . consolation, prayer, transcendence” – to untangle the complications of that story, which preoccupied Hughes for thirty-five years. Robert Graves’s The White Goddess was an important book for Hughes (and, he wrote, “for SP too, when I got her into it”), though he thought Graves lacked “real poetic imagination”. Peter McDonald reviews a new selection of Graves’s poems which reveals another dimension to this poet of the Muse, of “love and women”: his unsettling power as a poet of war. The “one story and one story only” at the centre of Graves’s poetry, too, turns out to be a more complicated one than we had thought, about a man who “chooses to be hurt again and again, and not to flinch”. “Lesbos”, one of Plath’s rawest poems of marital hurt and anguish, obliquely invokes the seventh-century BC Greek poet Sappho. The “secret” that two new poems by her had been discovered on a fragment of papyrus has recently travelled around the world, “often in garbled form”. Dirk Obbink, the head of the Oxyrhinchus Papyri Project, addresses the “key questions”, among them “how do we know they are genuine?”

The new Life of Penelope Fitzgerald is, according to A. N. Wilson, “the sort of tribute which is nowadays paid by publishers, by professors, by the literary world, when a considerable figure leaves us”; but it does not get to the heart of the novelist’s mystery. Magic and mathematics, rationalism and faith combined in the mind of Martin Gardner to give him a lifelong commitment to the marvellous: a “constant amazement and gratitude that we and a universe exist”. Michael Saler reads his “dishevelled memoirs”.

Alan Jenkins

February 5, 2014

Band-club opera in Malta

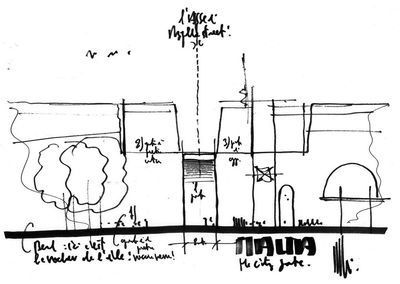

Above: A sketch by Renzo Piano: "South Elevation of the City Gate"; © RPBW

By CATHARINE MORRIS

To return to Hippolyte et Aricie ou la belle-mère amoureuse, which I saw at Teatru Manoel in Malta last month: a representative of the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles explained after the performance that opera parodies developed in parallel with opera in France. They were put on at fairground theatres, initially with real actors. The Comédie-Française tried to stamp them out by allowing only monologues – “so then you’d find one actor and one parrot . . . and ghosts were very popular”. When the Comédie-Française succeeded in forbidding even monologues, pantomimes were played; and when at last all real actors were banned, marionettes appeared. Marionettes have a long tradition throughout Europe, we were told – they were not invented in France, as you might imagine.

In the Maltese islands, too, opera is very much of the people. Many children’s first experience of live music comes through their local band clubs, which have been popular since the mid-nineteenth century; and two such clubs – both on Gozo, which has a population of about 30,000 – have venues large enough to accommodate full-scale operas. Both the Aurora Theatre, of the parish of St Mary’s, and Teatru Astra, attached to St George’s, stage one every October, and the competition is fierce. There was a time when the rivalry could become bloody, and our tour guide Mariella told us of a man who, because he belonged to the wrong band club, was unable to sit among the mourners at his friend’s funeral, so had to hover at the back. Today each theatre strives to outdo the other in quality and invention. Both count on armies of local volunteers to carry out admin work, make scenery and take part as performers – but they each also engage a well-known singer each year. The island of Malta itself has no large opera venue, so tickets sell out fast.

Valletta has been named European Capital of Culture 2018, and there is a general air of rejuvenation: the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, the creators of the Shard in London, are currently working on the renovation of Valletta’s city gate, the conversion of its Royal Opera House (bombed during the Second World War) into an open-air theatre, and the construction of a new parliament building. The Valletta International Baroque Festival will provide a suitably grand opening to the year, but I’m glad to hear that the band clubs will have a conspicuous place in the 2018 programme too. Part of Malta’s appeal is in its melange of cultural influences, and the Aurora Theatre is the only place I know of that accommodates under one roof an opera house, a social-club-style café with groups of men playing cards, and a statue of the Virgin Mary next to a boxing arcade game called Knockout . . . .

February 3, 2014

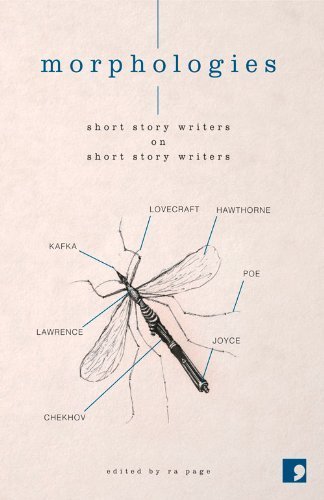

The short story: A hidden country still?

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Is the short story an endangered species?" is, as Joyce Carol Oates acknowledged in the New York Review of Books fourteen years ago, a "perennial question" – yet she came to the conclusion that, in the twenty-first century, it really would be. There were, are and will be great exponents of the form, but they would work under less "hospitable" circumstances, in a "radically diminished landscape", making the work of "generally reliable" and "heroically edited" annual anthologies "invaluable". I suppose we should count ourselves lucky that the publications Oates had in mind, including this and that, are still with us.

Over here in the UK, meanwhile, there's this, that and the other – the other, with which I have some peripheral involvement, being a slightly different way of making the short story thrive. I'd like to think that the £15,000 awarded to the winner of the BBC National Short Story Award and the £30,000 awarded to the winner of the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award will help to keep at least some short story specialists going for a little while longer.

For those still writing their entries to the BBC National Short Story Award (deadline: February 28), and for those of us who are merely readers of short stories (most recently, in my case, Charles Boyle's superb collection The Manet Girl), there is much to inspire and enjoy in Morphologies, just published by Comma Press. The subtitle is Short story writers on short story writers – more of a tongue-twister than "Poet to Poet", as Faber call their series of anthologies, but based on the same idea. Here, under the editorship of Ra Page, we have Sara Maitland writing about Nathaniel Hawthorne, Frank Cottrell Boyce writing about Anton Chekhov, Adam Roberts taking on the difficult task of writing fairly about Kipling ("simply the most technically gifted" of English short story writers), Ali Smith dismantling the opening paragraphs of the first three stories in Dubliners . . . and so on. (It's a pity Joyce wasn't available to return the compliment and write about the nifty opening paragraphs of Ali Smith.)

The main question is what makes a short story work. Smith describes those great Joyce stories as an "education in the ways not just narrative form but language itself works" – a notion you can catch a couple of minutes into this video, Alison McLeod's talk on (another Chekhovian) Katherine Mansfield, based on her contribution to Morphologies. Here she quotes Mansfield herself, speaking around the extraordinary moment of "At the Bay" et al:

"I do believe that the time has come for a new word, but I imagine the new word will not be spoken easily. People have never yet explored the lovely medium of prose. It is a hidden country still. I feel that so profoundly."

Each contribution to Morphologies ends with a list of essential stories, some of which are available in turn as eBooks. With some writers, the choice is so rich that it would be possible to choose almost entirely different lists; others are more predictable but useful reminders of what to turn back to (in search of pure pleasure or award-chasing inspiration or both). Here's an example of the first kind, I suspect, courtesy of Comma Press, Martin Edwards's selection of Arthur Conan Doyle:

J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement

The Red-Headed League

The Man with the Twisted Lip

The Adventure of the Speckled Band

The Adventure of the Copper Beeches

Silver Blaze

Lot No. 249

The Case of Lady Sannox

The Man with the Watches

The Leather Funnel

And the second kind? Well, maybe Toby Litt's recommendations from Kafka, who "created subject areas where other writers saw only frustration":

The Wish To Be a Red Indian

Description of a Struggle

Metamorphosis

Before the Law

In the Penal Colony

The Bucket Rider

The Problem of Our Laws

A Hunger Artist

Investigations of a Dog

The Burrow

It might have been of interest to these pre-Mansfield masters to learn that there was a hidden country of prose out there; great short story writers, then and now, create countries of their own.

January 31, 2014

Scarlett Johansson and SodaStream

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I was given a SodaStream for my birthday last year. As the donor occasionally reminds me, it was a generous present. Just as well then that it has become my most cherished gadget. Apparently SodaStream were big in the 90s, but I’m all for retro. And rather than spending a small fortune on bottled sparkling mineral water (sorry San Pellegrino) to which I’m addicted, I have my own readymade supply at home – and without the possibly damaging minerals of the bottled products.

As we have learnt over the past 24 hours, Scarlett Johansson (Vicky Cristina Barcelona etc) fronts an advertising campaign for the product. I didn’t know. And she’s an ambassador for Oxfam – didn’t know that either. The two are, according to Oxfam, irreconcilable because SodaStream is an Israeli-owned company operating in the Occupied Territories and Oxfam have clear guidelines there.

But as the BBC’s Middle East correspondent Kevin Connolly suggested on the radio this morning, it’s not so clear-cut. SodaStream is Israeli-owned but it employs 500 Palestinians, one of whom was interviewed; he praised the working conditions and pay and pointed out that this wasn’t a case of building houses on Palestinian land but rather an equal-opportunity job-creating plant. Ok, one employee doesn't necessarily represent the views of the whole workforce, but it was interesting to hear nevertheless. The company’s CEO Daniel Birnbaum meanwhile robustly rejected Oxfam’s stance.

Johansson has resigned her Oxfam role and will continue to promote SodaStream. Meanwhile I’ve had a thorough look at the literature that came with my product – very impressive it is too: the instruction manual, in many languages, is a thing of beauty. But where I would normally expect to read “Made in China” or “Made in the EU” there’s nothing. No “Made in Israel” and certainly no “Made in the Occupied Territories”. It’s almost as if it’s a stateless product.

But I’ll carry on using it, with pleasure. And that reminds me: I need to replace the CO2 canister this weekend.

Scarlett Johansson and Sodastream

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I was given a Sodastream for my birthday last year. As the donor occasionally reminds me, it was a generous present. Just as well then that it has become my most cherished gadget. Apparently Sodastream were big in the 90s, but I’m all for retro. And rather than spending a small fortune on bottled sparkling mineral water (sorry San Pellegrino) to which I’m addicted, I have my own readymade supply at home – and without the possibly damaging minerals of the bottled products.

As we have learnt over the past 24 hours, Scarlett Johansson (Vicky Cristina Barcelona etc) fronts an advertising campaign for the product. I didn’t know. And she’s an ambassador for Oxfam – didn’t know that either. The two are, according to Oxfam, irreconcilable because Sodastream is an Israeli-owned company operating in the Occupied Territories and Oxfam have clear guidelines there.

But as the BBC’s Middle East correspondent Kevin Connolly suggested on the radio this morning, it’s not so clear-cut. Sodastream is Israeli-owned but it employs 500 Palestinians, one of whom was interviewed; he praised the working conditions and pay and pointed out that this wasn’t a case of building houses on Palestinian land but rather an equal-opportunity job-creating plant. Ok, one employee doesn't necessarily represent the views of the whole workforce, but it was interesting to hear nevertheless. The company’s CEO Daniel Birnbaum meanwhile robustly rejected Oxfam’s stance.

Johansson has resigned her Oxfam role and will continue to promote Sodastream. Meanwhile I’ve had a thorough look at the literature that came with my product – very impressive it is too: the instruction manual, in many languages, is a thing of beauty. But where I would normally expect to read “Made in China” or “Made in the EU” there’s nothing. No “Made in Israel” and certainly no “Made in the Occupied Territories”. It’s almost as if it’s a stateless product.

But I’ll carry on using it, with pleasure. And that reminds me: I need to replace the CO2 canister this weekend.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers