Peter Stothard's Blog, page 44

May 2, 2014

Unmasked at last?

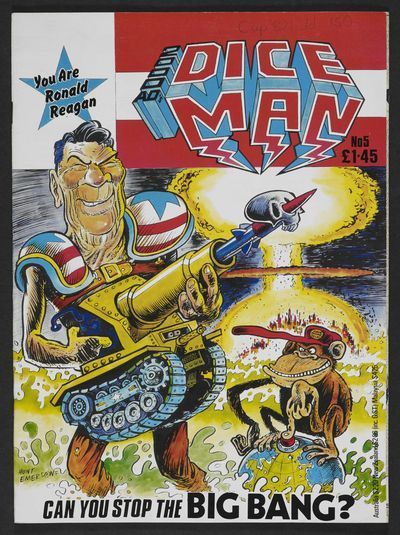

Diceman No5, by Pat Mills and Hunt Emerson (c) REBELLION AS All Rights Reserved

By MICHAEL CAINES

Not that I have ever considered myself an expert on the subject, but there is much on display at Comics Unmasked at the British Library that I haven't seen before, and some things I haven't even heard of – so in one sense, for me, the exhibition lives up to its name. But in another sense, it's no great surprise to read in the exhibition guide that comics are "much more than the stuff of childhood and nostalgia" ("No subject is off limits"). Mr Punch and Dan Dare are here, but so are Posy Simmonds's Tamara Drewe, Judge Dredd's helmet from the recent film adaptation (i.e. the good one, not the Sylvester Stallone version) and plenty of Alan Moore – the stuff of adulthood.

In fact, parents take note: this is an exhibition that comes with a content advisory notice, because of the potentially "offensive or disturbing" imagery, and visitors under sixteen have to be accompanied by an adult. The separate "Let's Talk About Sex" section can be bypassed if necessary – which is as near as the BL will ever get to mimicking certain sodden streets in Soho, I guess – although it is not so easy to skip the sections that feature bloodied bodies, vampiric gorgings and, if you swipe the right tablet screen (of which there are many, in fixed positions, scattered throughout the exhibition space), various Jack the Ripper scenes out of Moore's From Hell.

I arrived at the press view yesterday just in time to hear the curators talking about their hope that people who weren't already aficionados would go and see Comics Unmasked, which runs from today until August 19, and leave it with an increased respect for the artistry involved. In most rooms, although some display cases are too dimly lit for you to inspect the art closely (or read the speech bubbles), there is more than one reason to think that their wish might come true.

The range of inventive, esoteric approaches ought to impress people at least. Here are nineteenth-century precursors to the twentieth-century industry, in a George Cruikshank satirical print and the Illustrated Police News, as well as this page from the Northern Looking Glass (originally the Glasgow Looking Glass), published in the 1820s and identified here as the first-ever comic:

(c) British Library Board

Here also – in a section thickly populated with mannequins wearing the Guy Fawkes masks adopted from Moore's V for Vendetta by the Occupy movement and the Anonymous hacktivists – are politically motivated works such as the (mis)informative pages courtesy of the far-right political party the National Front, designed to make the self-respecting white youth aware of his rights, should he happen to be stopped by the police. Here are verbatim, illustrated reports from the residents of Archway in London; lurid superheroics gone wrong (in Kick-Ass, an American comic-book series co-created by the Scottish Mark Millar); and a massive, monochrome book, in which a series of minute panels, like the windows of a tower block, face a single massive panel, wordlessly contrasting tiny scenes from a circus with a single, bandaged-wrapped woman alone on a bus. The biopic trend in graphic novels is reflected in the glimpse below into the house of Joyce ("Jaysus", indeed; if only it was written it in the style of Finnegans Wake instead – although admittedly Dotter of Her Father's Eyes isn't entirely about Lucia):

Dotter of her Father's Eyes, 2012, by Mary Talbot, Bryan Talbot (c) Mary and Bryan Talbot

All that's missing here, then (as far as I could see), is Brian Braddock, aka Marvel's Captain Britain (created by another British-born artist, Chris Claremont): a physics student and product of Fettes (and Essex) who turns out to be destined to protect and . . . etc. You get the picture.

April 25, 2014

What do stamps say about nations?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Looking again at my stamp collection yesterday, I was struck by the variety and sophistication of so many of the items in my neatly ordered albums – the quality of illustration, the thought that had gone into producing them, the attempts at a narrative. I should say that I did my collecting in the late 1960s and early 70s and have no idea how stamps have developed since; indeed, until a few years ago I had assumed that I’d sold my not very impressive collection for beer money and so was delighted to come across it intact. Now I’m hanging on to it (it’s certainly not worth anything).

What do stamps tell us about countries? Maybe not much, but there must be an element of them representing that country to the rest of the world, even in these globalized times. After all, if we receive a letter or postcard from abroad do we not cast a glance at the stamp? I can’t help noticing that some countries back then put little or no effort into presentation (it may be very different now): India (surprisingly), Brazil (ditto), Argentina, and, to a lesser extent, Australia and New Zealand, which were very royal (cultural cringe?). Then there were the Scandinavian countries, with their unforgivably dull stamps, and almost equally dull Switzerland, East Germany, West Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium. Maybe that spoke of national self-confidence. I don’t seem to have any stamps from the Soviet Union so have no idea what they were like but I can imagine.

Greece, on the other hand, clearly took a lot of trouble: aside from some attractive images of traditional dress there is plentiful illustration of the classical heritage. France, as one would expect, drew on its artistic and cultural patrimony, Italy appeared not to (missing a trick there), while my Spanish section includes fifty-three representations of women in traditional regional dress, from Albacete to Zaragoza – I must have bought them as a job lot. Then there are the explorers Ponce de León and Cabeza de Vaca, and of course Franco is present . . .

Latin America has a lot of representations of Simon Bolivar the Liberator as you would expect (especially in the Venezuela section). Bolivia champions its (painfully slow) development – “el desarrollo” – and commemorates a South American tennis tournament held in La Paz in 1965; that city being at some 12,000 feet, it must have been quite a challenge to the players. For a more traditional image, meanwhile, see below:

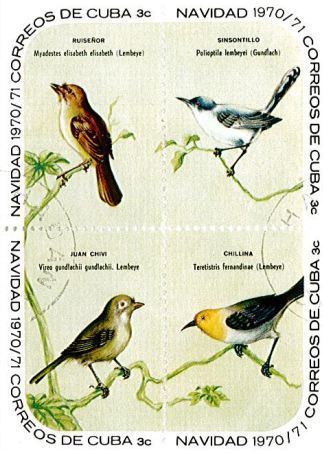

For Cuba it was no effort spared, whether it be bird life . . .

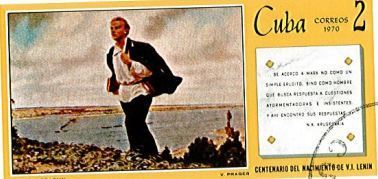

. . . or celebrations of Lenin's centenary (below).

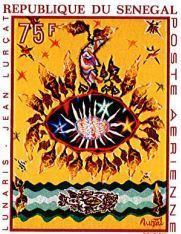

Africa, meanwhile, is a riot of colour and exuberance (see the stamp at the head of the post). Maybe there was a celebration of recently acquired Independence. What beautiful stamps, from Mauritania (commemorating both Lenin and Gandhi), to Mali, Guinea,

Senegal, Ghana to Ethiopia.

Further east, Yemen likes its cars (below), while a stamp from Afghanistan, dated 1970, reproduces the UN credo “We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war . . .”.

What of UK stamps? Lots of kings and queens – and there’s the 1964 Shakespeare Festival. Literary figures abound – I almost certainly had no idea who Wordsworth or Keats were, much less Inigo Jones. There’s the new Post Office tower, a spanking new hovercraft, the World Cup being held aloft, EFTA, the European Communities, 50 years of the BBC, the new universities, Concorde, the QE2, Churchill’s centenary, W. G. Grace, the wedding of Princess Anne and Mark Phillips in 1973. All very traditional. And then there are the historic buildings, castles and palaces. Just as last week a set of six stamps was announced illustrating Buckingham House (c.1700) to Buckingham Palace today. Plus ça change.

In Finland, and bizarrely on the same day, a set of three stamps was announced (to be released in September) celebrating the work of Tom of Finland (1920–91, real name Touko Laaksonen), who is chiefly known for his homoerotic (some would say pornographic) depictions of leather-clad (and unclad) muscular men. The three stamps don't reproduce his more explicit images and anyway, this being a family website, I’ve shown a mere detail from one of them.

I guess Sibelius, the architect Alvar Aalto and his works, the writer Tove Jansson and the Olympic runner Lasse Virén have already been covered, many times probably.

So one has to say: hats off to the liberal or liberated Finns for pushing the envelope, or should that be stamp? Probably best to keep those stamps when they appear away from any budding young collector though.

April 23, 2014

Get Georgian: part 2 – Hanover hangouts

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Back to the Georgian season, taking place in London and Hanover this year (see part 1 from last week): The Hanoverians on Britain’s Throne 1714–1837, the exhibition at the Lower Saxony State Museum Hanover, begins with two coins. “Rosssprung” (1714) shows a heroic, Hanoverian horse (“ross”) leaping across the Channel from Germany to Britain, marking the accession of George I. The coin next to it, minted over a century later at the end of the Georgian reign, depicts a rather more sedate steed plodding its way back to Germany. British humour from the German curators of the exhibition, perhaps.

And that’s not all we share – at first, the information panels, paintings and objects on display (similar to Queen Caroline’s fascinating closet of curiosities at Kensington Palace) are colour coded to indicate two separate nations (red for Hanover, blue for Britain). But the colours increasingly overlap as we progress through the eighteenth century. Key figures, other than the Kings and Queens, are featured, such as Jonathan Swift (I was surprised to hear from one of the curators that many Germans only know of Swift as a children’s writer), Handel, Johann Christian Bach (the eleventh son of Johann Sebastian, and the organizer, with Carl Friedrich Abel, of the Bach-Abel concerts in England), Captain James Cook and Jane Austen (who dedicated Emma to George IV). Pieces from the extensive art collection founded by George II’s illegitimate son, the Count of Wallmoden, are reunited since 1818, on loan from galleries including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid.

One of the stand-out objects, for me, is a letter written in Burmese script on pure gold, decorated with twenty-four rubies and contained in an elephant-ivory case sent from King Alungphaya of Burma to George II on May 7, 1756 (it took almost two years to travel from Burma to London). The Burmese King proposed a trade relationship: "kindest greetings to the English King who rules over the English capital . . . . When close friendship prevails between Kings of different countries, they can be helpful to the needs of each other which we are eager to fulfil" (this content was deciphered in 2011 after three years of examination). But George II wasn’t interested and sent it to his treasure store in Hanover.

Herrenhausen Palace, the summer residence of the eighteenth-century Hanoverians, has been rebuilt by Volkswagen after being bombed by the RAF during the Second World War. The exhibition it now houses looks at the period leading up to George I’s accession; in particular, at his mother, Electress Sophia of the Palatinate. She died in the palace’s baroque gardens during a thunderstorm, and there’s a memorial sculpture to mark the spot, alongside a fountain (one of the tallest in Europe) designed by Gottfried Leibniz and the mausoleum where George I is buried.

Ornate baroque architecture, frescoes and spiralled stucco ceilings of the palace’s original orangery (see photo above) and outdoor theatre provide the back-drop for the KunstFestSpiele Herrenhausen; a summer festival, that aims to showcase unconventional interactions between art forms. In 2011, Vivienne Westwood provided grunge-rococo costumes for the director Ludger Engels and the dramatist Andri Hardmeier’s bold take on Handel’s opera Semele, with catwalk-type staging.

Just outside the city of Hanover sits Celle Castle, the oldest residence of George I's ancestors. An exhibition on the Hanoverian dynasty is happening here, too. The surrounding town is pretty, with colourful, half-timbered houses (a “Latin school” from 1604 is still in use) and cobbled streets. At the entrance of a public park, I also came across “öffentlichen Bücherschrank”, a cabinet of free books – I’ve noticed them in Berlin before – and I saw a man with a stack, sat on a nearby bench. If only the Hanoverians had brought this idea with them to London, all those years ago . . . .

April 22, 2014

Shakespeare at 450

© National Portrait Gallery, London

In some ways, as the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth (some time this week, apparently) and baptism (known to have happened on April 25) comes round, it's business as usual. The RSC is staging Henry IV (both parts), while King Lear is playing at the National Theatre. Some new, relevant books have appeared with customary timeliness, and several of them are reviewed in this week's TLS, which boasts the familiar "Chandos portrait" of the author (above) on the cover for a particular, and rather extraordinary, reason. There'll also be, online, the second in our occasional series of readings, courtesy of the deputy editor, Alan Jenkins.

What else is going on? Well, the RSC is aiming both high and low, with a fireworks display (let's hope this goes better than Garrick's attempt) and, tomorrow morning, the first Twitter interview with its artistic director, Gregory Doran. Shakespeare's Globe are hosting a series of lectures by distinguished Shakespearean scholars, and David and Ben Crystal will be returning to the question of original pronunciation. The BBC's contributions seem to be limited to Radio 3, including a production of Antony and Cleopatra with Kenneth Branagh and Alex Kingston that you can still catch the iPlayer way. Shakespeare 450, a week-long conference in Paris has just kicked off, courtesy of Société Française Shakespeare, in which commemorating and celebrating Shakespeare has itself become a notable part of the programme, among many other themes.

Those for whom inspiration lies in another direction may content themselves with entering the V&A's (ahem) Cakespeare competition, which has its own Pinterest page – rather extraordinary, too, in its edible way.

For my part, after mildly threatening to do my Shakespeare reading in private, I've more wildly volunteered to read a sonnet or three as part of the Complete Reading running tomorrow from 10am at London's Guildhall. The other readers include Damian Lewis, Alan Hollinghurst and TLS contributor Judith Flanders, so come along if you can: the standard of reading should be very high, from Sonnet 1 to 154, apart from a possible dip around the mid-60s.

And of the potentially controversial announcement of the discovery of Shakespeare's annotated copy of John Baret's Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie, there will be more later – for now, let's just note that among the earliest to take gleeful note of the claims of George Koppelman and Dan Wechsler is Forbes.com, for whom there are generally applicable lessons for entrepreneurship here: "here's how a great find or new invention within your industry can impact your business". It beats waiting 400 years, I suppose.

April 17, 2014

Pardon my French!

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

There was a very unfunny TV sitcom in the late 1970s called Mind Your Language. It was set in a language school and its basic thrust, as I vaguely recall, was that foreigners are inherently funny and fitting targets for comedy (as the photo of the cast above suggests), particularly as they struggle with the English language. As a nation we Brits are pretty good at laughing at foreigners of course (some would say we’re quite good at laughing at ourselves too), never more so perhaps than in that other 70s sitcom Fawlty Towers – but that was a work of genius and so is exempt from criticism. I’m talking about unfunny mockery here.

Is there any correlation, I wonder, between our mild xenophobia (not so mild in the case of the 1980s Sun newspaper) as expressed in programmes like Mind Your Language and our generally poor language accomplishments? Britain must be one of the most monoglot nations on the planet, in spite of the influx of immigrants and foreign workers. I’ve sometimes been made to feel as if having a passing acquaintance with the language spoken by people who live 20 miles across the Channel is something to be embarrassed about. Pardon my French!

And I sense that few of our leading politicians, with the exception of Nick Clegg, have any sort of command of a second European language. Not David Cameron I’m sure, who is temperamentally anti-European I sense, or Ed Miliband, or our dogged foreign secretary William Hague. Clegg is a notable exception, but then he’s a Liberal Democrat and therefore pro-European and of course his lawyer wife is Spanish. His progressive views (and broken electoral pledges) make him an easy target for the popular press but, to his credit, he seems happy to play the role of political punchbag. Viewers gave the UKIP leader Nigel Farage the edge over Clegg in their recent televised debates: Farage, the plain-spoken pub bore (who, being an MEP, I suspect must speak more than one European language but doesn’t let on), bested Clegg the Europhile and slightly dry technocrat.

Where do these failings – if failings they are – begin? The Guardian recently published an article pointing out that “the number of students taking a language degree is at the lowest level in a decade”, citing a 22% (22!) drop in numbers between the academic years 2010–11 and 2012–13. The figures are taken from a report put out by the Higher Education Funding Council for England, whose author Janet Ilieva writes: “A worrying fact is that the data has seen a fall in applications to foreign modern languages in 2013–14”. John Worne, director of strategy at the British Council, is quoted as saying “While it’s good to see more young British people going into higher education, it’s disappointing that language courses aren’t benefiting from this upward trend, with yet another dramatic decline in students taking languages”. Disappointing indeed.

I took soundings from modern language academics among TLS contributors (all of whom, by chance, happen to be teaching at Oxford) and was told that for Italian, Oxford and Cambridge are bucking the nationwide trend of falling numbers (and department closures). Where Spanish is concerned, meanwhile, according to Ben Bollig, Fellow and Tutor in Spanish at St Catherine’s College, “We have no shortage of good applicant. Indeed there are many applicants who I’m sure are very good and potentially very worthy of a place, but we can’t admit them all, sadly”. He continues: “Given that a number of universities have reduced their provision or closed down language departments, it’s probably there that we see the overall fall in numbers. Teaching modern languages is expensive in comparison to other arts and humanities subjects, in that you have to teach the language (normally in quite small groups) as well as the ‘content’. But there are some encouraging signs elsewhere. Warwick opened a new Spanish department and Reading is doing so for 2015. I hear Spanish is doing very well at my previous employer, Leeds. Oxford is fortunate to be well resourced and through the collegiate system and the tutorial model able to offer precisely the sort of teaching that mod langs students require.”

Meanwhile Ritchie Robertson, Taylor Professor of German at Oxford, writes that “applications in Modern Languages are healthy, though (at least in the case of German) this requires a lot of dedicated outreach work”. But Patrick McGuinness, Fellow of St Anne’s, where he lectures in French, is rather less sanguine. He tells me that “from an Oxford perspective we spent about ten years thinking we were ok because our applications numbers held up. But probably we aren't in the long run – unless we accept more and more students from private schools the way classics have had to do . . . . The rot set in when they took literature out of GCSE and A level and concentrated on language skills unmoored from cultural and grammatical knowledge. The result is that people who used to do languages because they loved literature turned away from it (old A level combinations used to be English, history plus language or English plus two languages) and those who did it are not noticeably better at language than before. Also important to remember that teachers who like literature used to teach languages and that has also changed.”

Back in the day when I read French and German at King’s College London, the course was roughly – as I recall – 60 per cent literature and 40 per cent language (any more language would have been frankly intolerable). I regarded it as being like doing English but with a foreign language (or two) thrown in. Particularly where German was concerned it meant that I read texts that I would never otherwise have come across (see above) while assiduously avoiding others (anything medieval). I’m grateful to have had that exposure: it was good to get a sizeable amount of Thomas Mann’s work under my belt, for example. Those Reclam editions I’ve pictured above, with their very yellow covers and tiny font size, cost 60p (one of them still has a price label on the back) from Grant & Cutler near the Strand (where it once was), or Dillon’s in Gower Street. I recall one of my peers telling me immediately after Finals that he was taking his whole collection down to the bookshop to sell them! I can’t imagine he would have got very much for them.

Meanwhile, my elder daughter is learning both French and Spanish at her Secondary academy, and loving it – which is great. So far, however, there has not been a literary text in sight, but that could change next year. I hope so.

April 11, 2014

The art of Marguerite Duras

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

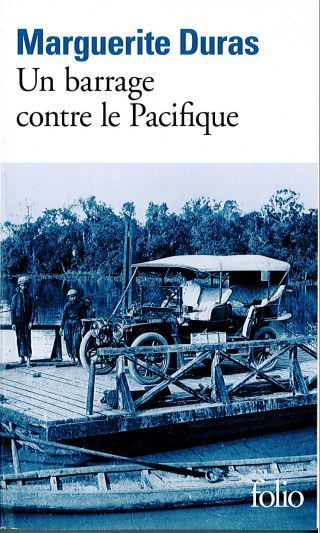

Marguerite Duras won the Goncourt prize in 1984 for her novel L’Amant (The Lover), a compressed, stylistically brilliant autobiographical account of a love affair between a fifteen-year-old girl and a twenty-seven-year-old Chinese man she meets on a ferry on the Mekong river in Indochina. The author described the book as a “photograph album”. Although the narrator writes early on, “the story of my life doesn’t exist”, this is clearly a tease as Duras cannibalized her life for her fiction, reworking episodes repeatedly, obsessively – a process that reached its apotheosis in L’Amant. Her life is all too present in her work.

She was born Marguerite Donnadieu a hundred years ago, on April 4, 1914, in Saigon (and died in 1996). She took the pen name Duras from the wine region where her father once owned a house. Her parents, both teachers, had answered a government call for citizens to pursue a career in French Indochina, but her father soon fell ill and returned to France where he died when she was a young child, leaving her mother, still in Indochina, to bring up three children on her meagre teaching salary, an unsmiling presence in the “photograph album”. Duras herself only visited her mother country once during her childhood, but returned there to finish her studies.

It’s tricky to get a proper handle on Duras’s oeuvre as she worked in more than one medium and in the 1970s turned increasingly to film. According to David Coward, writing in the TLS (May 21, 1999), there are “sixty-three works of fiction, twenty films, twenty-five or so plays and theatrical adaptations”. By my reckoning she published twenty-odd novels, the other works of fiction being novellas and short récits. Added to which, writes Coward, there have been “thirty-three monographs since 1970” (and counting). Coward goes on to say “Duras has cornered the world PhD market in French studies”. She is the “voice of French Literature in our hero-hungry fin de siècle”. This was in 1999; it could be said that voice now belongs to Michel Houellebecq. Just as there is an adjective houellebecquien, people have talked of situations or moods being “durassien”.

Duras’s return France in the 1930s to complete her education led to marriage to Robert Antelme. The couple became active in the Resistance and Robert was deported to Ravensbrück, from where he returned weighing 37 kg. The marriage didn’t last much beyond the war (they lost a child early on) but Robert’s story was the source for the powerful La Douleur (1985). According to Duras’s biographer Laure Adler, Antelme was indignant when the novel appeared, feeling that his experience should have remained a matter private to him (although he did write about it himself). The book is also a clear-eyed and unsparing account of wartime collaboration and its consequences for the perpetrators, while General de Gaulle is particularly unflatteringly depicted as someone who despises “le peuple”. Duras had a close friendship with her contemporary and de Gaulle’s onetime political rival François Mitterrand (who attended her Goncourt prize lunch) but how much did she know, one wonders, about Mitterrand’s wartime tergiversations? Her decision to join the Communist Party towards the end of the war appears to have been motivated by the hope of thereby getting news about the imprisoned Robert. She resigned her membership in 1950 and went on to describe Communism as a disaster. But she did sign manifestos against the war in Algeria, spoke up for feminism and gleefully joined the students in ‘68.

Recurring themes in her work – desire, infidelity and betrayal, alcohol, transgression, prostitution, thwarted ambition, sorrow (“geindre”, to moan or whimper, is a verb that occurs frequently) chime with what Duras professes in Les Lieux de Marguerite Duras, an in-depth and beautifully illustrated interview with Michelle Porte published by Minuit in 1977: “On n’écrit pas du tout au même endroit que les hommes. Et quand les femmes n’écrivent pas dans le lieu du désir, elles n’écrivent pas, elles sont dans le plagiat” (“ . . . when women don’t write about desire, . . . they’ve entered the realm of plagiarism”). Discuss!

Also in that book she captions a photo of herself (looking like something out of Bugsy Malone) with her brother (above) “my brother Joseph from Un Barrage contre le Pacifique. He died very young during the war, for lack of medicines”. Un Barrage contre le Pacifique (1950, The Sea Wall), Duras’s third novel and set in Indochina, is unquestionably her masterpiece, and Joseph a very vivid presence in it, a boorish but physically attractive twenty-year-old womanizer who is both protective towards his sixteen-year-old sister Suzanne and seeks to exploit financially the fact that she is being relentlessly pursued by a rich but unprepossessing young colonial Frenchman. The siblings live with their widowed, bankrupt and depressed mother, who has given up on her doomed agricultural projects and financially ruinous attempts to build a sea wall (which was her mother’s experience). Duras explores relations between the French colonizers, of whom the family were not representative in that they went native, learning Vietnamese and swimming in the rivers. Duras’s own mother, on whom the mother is clearly modelled, disapproved of the novel.

While it would be easy to think of the mother figure in Duras’s fiction as harsh, unloving, worn down by suffering and broken dreams, there is a moment in L’Amant de la Chine du Nord (1991, The North China Lover) when the mother exhorts her children to observe nature, to listen to the sounds of the night (they are living on the edge of the jungle); she tells them about injustice, war and death and reminds them that they are children of Indochina rather than mere colonialist intruders. (And her second novel, La Vie tranquille, published in 1944, is dedicated to her mother.) Did her younger brother utter the wonderful line “La lune elle réveille les oiseaux” (the moon wakes the birds up) as the little brother does in L’Amant de la Chine du Nord?

This novel is an interesting case, being a reworking of L’Amant and prompted by the appearance of the film of the earlier book she had worked on with the director Jean-Jacques Annaud. She disapproved of Annaud’s interpretation and disowned the project. The book was in a sense a rejection of the film, and was dedicated to Thanh, her Chinese lover of many decades before, whose death she had recently heard about.

Duras had a highly productive middle period producing some of her best work in the years 1958–60: Moderato Cantabile, a novella about a near-affair between the wife of a factory owner and one of his employees, set in a seaside town in northern France, which is a minor masterpiece; the wonderful Dix Heures et demie du soir en été, set in Spain (10.30 on a Summer night) , the film script Hiroshima mon amour (1960); and L’Après-midi de Monsieur Andesmas, which evokes vividly the scrubby sun-scorched hinterland behind Saint-Tropez. Others would no doubt cite Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964, The Ravishing of Lol Stein).

Then there is the (rarely performed) work for the theatre, in four volumes, including versions of Henry James’s The Aspern Papers and Strindberg’s Dance of Death, and the numerous film scripts.

Hiroshima mon Amour (above) was of course made into a film by Alain Resnais, who died earlier this year aged ninety-one. Resnais is probably best known for the cinematically very beautiful Last Year at Marienbad, but personally I much prefer Hiroshima mon amour. Starring Emmanuelle Riva (“seductive rather than beautiful”, as Duras rightly says) and Eiji Okada, it portrays a brief affair between a young French woman who has come to Hiroshima to appear in a “film for peace” and a young Japanese architect; both are married, she with children. We see a sanitized, almost stylized city, recovering from its trauma; the woman has her own trauma to deal with: the brutal death of her German soldier lover when she was eighteen in the last months of the war and living in the Loire town of Nevers, and subsequent rejection by her mother and pharmacist father. It is a masterpiece.

On May 13 Gallimard will be publishing Volumes 3 and 4 of Duras’s Oeuvres complètes in their prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Volumes 1 to 4 will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

April 8, 2014

Get Georgian: part 1

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

George I’s behaviour was awful. He locked up his wife Sophia Dorothea in a remote German castle for adultery with a Swedish count, took their children and his mistress to England when he succeeded to the British throne in 1714, and made sure his wife was forever kept away from the family. He would later kidnap his grandchildren from the future George II and his wife Queen Caroline.

These were just a few of the anecdotes about the Georgians related to us by Lucy Worsley (the Chief Curator of Historic Royal Palaces) at a preview of The Glorious Georges, a year-long celebration to mark the 300th anniversary of the Hanoverian accession to the British throne. A season of exhibitions and events will take place at palaces in London and Hanover, where Celle Castle and Herrenhausen Palace will form part of The Hanoverians on Britain's Throne 1714–1837.

George I was an unlikely king – he was fifty-second in line to the throne and fifty-four years old. But his mother was the granddaughter of James I and, more importantly, George was the nearest Protestant. Unremittingly German (he could only speak broken English when he first arrived), and flanked by his mistresses “The Maypole” and “The Elephant”, George told the British that they were “the best-shaped . . . and lovingest people in the world”.

Rivalry between the four Georges (here’s a helpful song to identify them) provided endless entertainment to the British court and the public; not least because George I and his son were always trying to trump each other’s parties. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s polemic sonnet “England in 1819” turns against George III (“old, mad, blind, despis’d, and dying king”) and the Georgian reign (“leech-like to their fainting country cling”). The period defines much of modern Britain and Britishness – such as tea drinking, coffee-houses, newspapers, the birth of consumerism, art galleries and the cult of celebrity – all of which could only be enjoyed by well-to-do, white, Protestant males (some of this is, perhaps, still the case . . . ). Georgians Revealed, a recent exhibition at the British Library, offered a prologue to the anniversary; as Norma Clarke put it in her review for the TLS, “It is acknowledged that Georgian Britain was a kingdom of ‘extremes’, but the poor feature only in parenthesis and the gargantuan wealth of the few is underplayed . . . . In this the exhibition obeys the dictates of Georgian etiquette. The inescapably ‘low’ aspects of life lacked style and were best not noticed”.

Gin, gang culture, addiction and slavery are far from evident on the London leg of the season, too, but each palace has been cleverly curated to represent the king who lived there – Hampton Court Palace focuses on George I, Kensington Palace on George II, and Kew Palace on George III and George IV – as well as the lives of the courtiers; not always as glamorous and refined as I’d thought. George II’s mistress Henrietta Howard wrote in her diary that her rooms in Kensington Palace were so damp she could have grown mushrooms, Tracy Borman, joint curator at Kensington Palace, said. And as we toured the King’s public dining room at Hampton Court, Worsley described the crowds of courtiers as “stinking in abundance”, jostling to get closer to the King and Queen (there will be a “Smell Map” at Hampton Court and Kensington Palace recreating distinct court scents, such as wood smoke and herbs used in the rushing floor to mask body odours). Elaborate white napkin sculptures adorn the tables and a chicken-wire barrier protects the royals from the crowd – just as it did in the eighteenth century. Restored paintings of feasting and food, by artists such as Rubens, hang on the crimson damask silk wallpaper.

The conservation work in the newly opened state apartments of Kensington Palace and Hampton Court is fascinating. Each detail required extensive research and specialist makers, from gold-gilders for the cornices to limewood experts to restore a carving by Grinling Gibbons (known in the 1680s as the “King’s Carver”) that now decorates the fireplace of the Presence Chamber in Kensington Palace.

During the restoration process, the builders found tools, rags, cigarette butts and bottles in attic rooms, left behind from when the palaces were first built and decorated. At Hampton Court they also discovered hand-prints and graffiti by Christopher Wren’s workers, and, on a wall in its restored Chocolate kitchen, you can see a crude pencil sketch of the view up a female courtier’s skirt – probably, Worsley said, drawn by a bored page boy “below stairs” waiting to serve drinking chocolate.

We saw a magnificent mantua made from silk and woven with untarnished silver thread (thought to have been worn only once by Mary, Marchioness of Rockingham when her husband Charles became Prime Minister in 1765) and a pink linen, whalebone hoop (an undergarment used to extend women’s hips at court, usually to a metre wide), both of which will be on display at Kensington Palace. (No doubt these women would have looked otherworldly and elegant, but I imagine they couldn’t do much – there are contemporary descriptions of the ladies at court slowly gliding about as if they were on casters.)

“Revisionists of the revisionists”, Borman explained, now say that the Hanoverians created an environment for culture to thrive, championed by Queen Caroline and her circle of intellectuals (which included Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Gottfried Liebniz and Sir Isaac Newton). Reviving this spirit, the palaces will be running “salons” with guest speakers debating Georgian and twenty-first century issues.

Many other events are scheduled for the next few months, for example choral anthems, oratorios and chamber music from the Gabrieli Consort and Players; cookery and chocolate-making classes; Georgian “selfies”, if you make it to the centre of Hampton Court’s maze; a performance from a thirty-piece orchestra of George Frideric Handel’s “Music for the Royal Fireworks”, accompanied by a sculptural firework display (recreating the original commission for George II in 1749; see picture, below); and there is also the alluring invitation to learn everything you need to know about the royal “wee” . . . .

April 7, 2014

Books at Bateman's

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

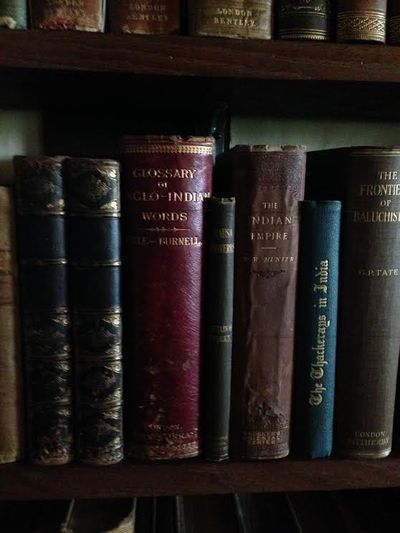

Rudyard Kipling’s bookshelves at Bateman’s in East Sussex are, as you would expect, well stocked. Kipling bought the Jacobean house with its 33 acres in 1902. By this time, he was, at the age of thirty-six, “the most famous writer in the English-speaking world”, to quote the leaflet from the National Trust, in whose possession the house now rests. (Elsie, the only one of his three children to survive into adulthood, bequeathed the property to the Trust when she died childless in 1976.)

In a recent article in the Commentary section of the TLS (March 28), Malyn Newitt, an emeritus professor of History at King’s College London, cites the Trust’s mission statement on its website, with its pledge of access to everyone. Newitt goes on to suggest that “Opening [the properties] up for ever, for everyone does not, however, seem to apply to its libraries”. The piece is accompanied by a photo taken at a Trust property, Lanhydrock in Bodmin, with its bookshelves showing metal bars across the book spines, making it impossible for the casual visitor to browse.

But David Pearson, in a letter published in this week’s issue of the paper (Letters, April 4), suggests that Newitt’s article is “unduly negative, and unrealistic in its criticisms”, pointing out that “the houses are full of historic objects which visitors are not able to use in the ways their makers intended – we do not sit on the chairs, walk on the rugs, or lie on the beds, because if we did, that heritage would be destroyed in a season” (Pearson is Director of Culture, Heritage & Libraries at the City of London Corporation).

I have to say I’ve never felt the urge to pick a book off the shelf in a National Trust property (it’s enjoyable just to consult the spines, particularly when one sees books such as The Thackerays in India, above), but I guess Newitt’s point was a slightly different one – that the libraries may contain books useful for research that are not easily accessible elsewhere. In which case, as the historian David Rundle offers in another letter in the same issue, it’s an idea to “contact [the staff] before arriving” and they will invariably be “helpful, forthcoming and quite willing to arrange a consultation”.

Bateman’s has other pleasures to offer apart from the books: Indian memorabilia, of course, including a sequence of plaques (see below) executed by Kipling’s father,John Lockwood Kipling who, as well as being a museum curator in Lahore, illustrated scenes from his son’s Indian stories. And, as always, there are the volunteers, who are keen to step forward and unburden themselves of everything they know about the room you have just entered.

Not forgetting the Vegetable Garden, with its carefully labelled plants, some of which I had never heard of: angelica, bugle, toadflax, soapwort, sneezewort, alecost . . . .

April 3, 2014

i.m. Anne-Catherine Phillips, artist and friend

By Peter Stothard

The painter, Anne Catherine-Phillips, died yesterday – without notice and too young. She was so calm in her pictures of seas and cities, so shocking in her departure. For her friends there remain the quiet places she brought to life, the libraries and workrooms and empty beaches. This one is called "Mending". I am not going to telephone her husband, one of my oldest friends, to check its date – or her dates. There will be time enough later to remember much and more precisely. Today this is for a gentle woman and the work that is there to see.

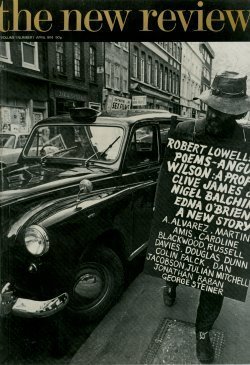

Sounding out Ian Hamilton

By MICHAEL CAINES

Is it true now, if it ever was, that there are only – or as many as – 100 serious poetry readers in Britain? That's the sombre estimate or elitist quip, as you prefer, of an "anonymous pundit", quoted by Julian Symons back in 1960, and quoted again by David Collard in this week's TLS. Twenty-first-century authors of slim volumes and publishers of little magazines might be ruefully moved to concur. Yet they go on writing, editing and publishing, and some of them, the review copies tell me, half-hope to shift 100 units.

Or perhaps the practice of writing poetry isn't just about the money. Is this a concept our market-led world is ready to hear?

Anonymous pundits and others with a serious attachment to poetry might enjoy hearing this, at least: Alan Jenkins, poetry editor of the TLS, talking (briefly) about Ian Hamilton, and reading a selection of Hamilton's poems:

It's the first in an occasional series of readings from the TLS (head for the TLS SoundCloud page to hear more in due course), and accompanies Collard's account of how the last of the four magazines Hamilton edited, the New Review, took the lion's share of the available funding for literary magazines in its time, but still struggled to keep going – and how, poetry aside, its reputation as the work of a clique belies its actual achievements, not least in terms of publishing women writers, such as Jean Rhys, Lorna Sage and Iris Murdoch, at a time "when the literary establishment was a largely male domain".

Hamilton was a poet who knew a great deal about the difficulties of running literary magazines. His own poetry, for instance, "all but dried up" during what he called his "trashy years" – the years of amassing debts, hiding from creditors and lagging behind with what was meant to be a regular publication schedule. The Collected Poems (edited by Alan) comes to a lean 160 pages. In them, you'll find such extraordinary things as "Newscast" ("The Vietnam war drags on / In one corner of our living room . . ."), "The Storm" (the first poem Alan reads), "Rose" and "Father, Dying". If ever a poet deserved more than 100 readers – well, here he is.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers