Peter Stothard's Blog, page 46

March 10, 2014

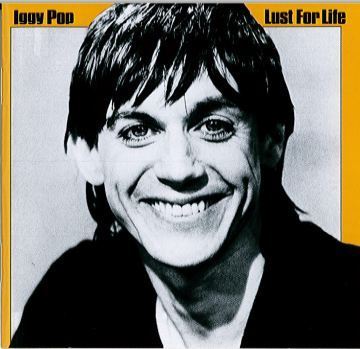

Jarvis Cocker to Iggy Pop: the handover

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I’ve always suspected Jarvis Cocker (above) to be a man, if not of wealth and taste, then of style and taste. Proof positive came in the form of his Sunday afternoon show yesterday on BBC Radio 6 Music, the second hour of which the Pulp singer devoted to Iggy Pop, or “Mr James Osterberg” as he mock-archly called him, in that inimitable Sheffield drone. This was reason enough, on a beautiful spring afternoon, to stay in and do the ironing.

The reason for the tribute? Cocker is taking a long sabbatical and handing the cans over to Iggy Pop for the next few months. Cocker is clearly thrilled at the succession, never more so than when he spoke to his stand-in on a dodgy phone line to Miami (“how’s the weather over there?” etc).

Mr Cocker confessed to being in awe of Mr Osterberg. He even at one point talked of the “genius of Iggy Pop”. Going too far? I don’t think so. If one definition of artistic genius is the ability to take the art form in question in new directions then Iggy Pop qualifies. With his brilliant band The Stooges, Pop redefined rock and roll and paved the way for punk rock – not for nothing is he regularly called “the godfather of punk”.

I confess that this is not the first time I’ve blogged about Iggy Pop. And what has any of this to do with literature, you ask? Well, as respondents to that earlier post revealed, Iggy Pop can count Michel Houellebecq among his admirers and, as we were also reminded, he composed a charming short essay about Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.

Cocker took us breezily through Iggy and the Stooges’ career with contributions from David Bowie (who referred to Pop as “Jim”) and Johnny Marr of the Smiths, who rates Raw Power (1973) the one album he could not do without. Good choice: it is so much more than 34 minutes of demented brilliance after all.

I hadn’t realized until yesterday that Pop provided backing vocals on one of David Bowie’s Berlin albums, Low. The Bowie–Pop Berlin collaboration was of course very fruitful, yielding The Idiot and Lust for Life, some of Pop's finest work (and Bowie, who knew a good thing when he saw one, incidentally also produced Raw Power). I had also forgotten that the song “Lust for Life”, as well as being used to such good effect in Danny Boyle’s film of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, made an earlier appearance in the 1980s film Desperately Seeking Susan with Madonna. And I hadn't before heard his beautiful rendition of the John Barry song "All the Time in the World", or his collaboration with the French chanteuse Françoise Hardy.

And Iggy Pop, who has always struck me as being essentially without ego, declared himself thrilled to be taking over the show. Any ideas as to what he'll choose to play?

March 6, 2014

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

Our late and much-loved friend Christopher Hitchens liked to speak of places that produced more local history than they could consume: Cyprus and Ireland were two of them and Crimea is most certainly another. The news stories this week from Ukraine bring back again the surplus stock of war and deportations, sullen minorities, mythic heroism and the mess made by all those distinguishing right from wrong from a distance. The TLS leaves news to others but there are twentieth-century echoes this week in the letters of the American poet, critic and Stalinist sympathizer Malcolm Cowley, reviewed by Marc Robinson. Cowley was “a dedicated fellow traveller but never a Communist Party member”, an artist who saw himself both near to and far from the camps, the famines and the show trials. The letters, “sensitively compiled and annotated by Hans Bak”, return compulsively to the question of his loyalties, the paralysis of his inaction and the “normal instinct” for comity with Russia. Our Commentary explores the poetry of Varlam Shalamov, the author of Kolyma Tales, generally recognized by Russians as “the greatest work of literature about the Gulag”. His poems, unpublished before perestroika and bowdlerized since, are about writing, reading, religion and a distance from the external world. Influencing Tomorrow is a book co-edited by Douglas Alexander, the man who may be dealing with Moscow if Labour wins the British election next year. Charles King notes “the combination of hubris and timorousness that is the stock-in-trade of the foreign policy establishment in Western democracies”.

Kathleen Burk reviews “a convincing and important contribution to national and international history” by Richard Roberts, noting the decisive response by David Lloyd George to the little-remembered financial crisis of 1914. David Watkin praises an unusual account of the colours that have come to be typical of Rome over the centuries, four of which appear on our cover this week. The Renaissance past, it seems, was paler than we might expect. The deluxe edition of John Sutcliffe’s book contains nine essential pigments for producing the more familar effects at home.

Peter Stothard

March 2, 2014

March 1, 2014

The ‘people of the shadows’ enter the Panthéon

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

France doesn’t have an equivalent of Poet’s Corner in Westminter Abbey, which is perhaps surprising for a country that lionizes its writers. Presumably after the separation of church and state at the beginning of the last century, the idea of commemorating its writers in Notre Dame Cathedral would have been out of the question.

We know that France lionizes its writers from a glance at city and town street maps: Quai Voltaire, Boulevard Victor Hugo, Avenue Stendhal, rue Arthur Rimbaud and so on. And then there are the historical and political figures: you’d assume that the reason the main thoroughfare in Aix-en-Provence is called the Cours Mirabeau would be that the Revolutionary leader had been born there, but he wasn’t; he did serve there politically, however, elected to the Estates-General for the city in 1789. Elsewhere Napoleonic and World War One generals feature prominently – Avenue Jean Lannes, Avenue Gallieni, while every town and city seems to have an Avenue Maréchal Foch. And then there are the lycées: Lycée Paul-Valéry, Lycée Jean-Paul Sartre, Lycée Simone de Beauvoir . . . .

In Britain we seem to do things differently: our street names are resolutely unliterary – ok, there is Poet’s Corner in Acton (and an undistinguished Voltaire Road in Clapham), but it’s not exactly the Strand or Piccadilly. Perhaps we prefer to hide our literary lights under a bushel. And anyway our towns and cities don't have boulevards and avenues on the French model.

No Poet’s Corner then, but Paris does boast the chilly Panthéon in the Latin Quarter, with its famous inscription “Aux Grands Hommes La Patrie Reconnaissante”. Built as a church, it was deconsecrated during the Revolution when Mirabeau decreed that it should become a mausoleum for the great (he was the first to be interred there). Other residents in some shape or form include Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, whose funeral procession in May 1885 was witnessed by huge crowds (and has been described by the historian Robert Tombs in his Introduction to Christine Donougher’s new translation of Les Misérables as one of the great state occasions of the century), Alexandre Dumas (controversially reinterred there in 2002), Émile Zola, Pierre and Marie Curie (the second woman to be buried there, and the first in her own right) and André Malraux. Then there is the Resistance hero Jean Moulin, who was tortured and murdered by the Nazis in 1943. President de Gaulle had his remains transferred to the Panthéon in 1964.

Moulin has now been joined by four other figures from the Resistance: two women (i.e. the third and fourth) and two men. Germaine Tillion (1907–2008), an anthropologist at the Musée de l’Homme, was betrayed and deported to Ravensbrück, from where she escaped weeks before the end of the war. She later took up the cause of Algerian independence. Also sent to Ravensbrück was Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz (1920–2002), a niece of the General. She was liberated from the camp in April 1945, and gave evidence at the trial of the “Butcher of Lyon” Klaus Barbie in 1987. Jean Zay (1900–44) was a minister in the Front Populaire government and co-founder of the Cannes Film Festival (yes, it predates the war). He was assassinated by the collaborationist Milice. The journalist Pierre Brossolette (1903–44), who was something of a rival to Moulin, was tortured by the Gestapo and took his own life rather than betraying his accomplices. There are said to be nearly 500 streets in France named after him, but he has rather remained in Moulin's shadow..

Clockwise, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Germaine Tillion, Pierre Brossolette and Jean Zay

As Le Monde pointed out, the striking aspect of this decision to honour the quartet, rubber-stamped by President Hollande, is that they’re relatively little known to the public. The decision hasn’t met with unanimous approval: the historian Mona Ozouf calls it “coherent and indisputable”, while Pierre Nora, the historian and architect of the Lieux de mémoire volumes, finds it “striking that the 1914–18 war, whose centenary we are marking this year, should be absent [from the list of names of people being honoured]”. He suggests the Unknown Soldier. Yet according to him, the Resistance is the only element able to provide national cohesion in a divided country. Meanwhile the Bulgarian-born essayist (and co-author of a book on Tillion) Tzvetan Todorov reckons that the choice of Tillion and de Gaulle-Anthonioz is appropriate because their fight went beyond their time in the Resistance as they took up arms on behalf of the destitute and the colonized.

In his excellent book The Resistance: The French fight against the Nazis (2009), Matthew Cobb writes of how “Moulin was metaphorically resurrected in December 1964, when his ashes were buried in a moving state ceremony at the Panthéon. André Malraux, who was Minister of Culture and had played a minor role in the final stages of the Resistance, made a speech . . . that has entered French history. The oration turned into a shamanic invocation of the spirit of the Resistance as Malraux, in a voice trembling with emotion and cracked by decades of tobacco abuse, described the terrible sacrifice made by Moulin and ‘the people of the shadows’”.

February 28, 2014

Austen vs. Brontë

By ROZALIND DINEEN

The billing was Jane Austen vs. Emily Brontë: the Intelligence Squared Queens of English Literature debate. The auditorium was completely full. Professor John Mullan (UCL) spoke for Austen, novelist Kate Mosse was for Emily Brontë; actors Mariah Gale, Eleanor Tomlinson, Dominic West and Sam West played out the advocates’ favourite scenes. Polite and genteel it was not.

But neither – Mullan argued – was Austen. Some of her characters are ghastly, he said, and being with them is hell … but you cheer every time they walk into the room, don’t you? Mullan beguiled on Austen's behalf: she is so simple and yet so complicated, she is the writer who invented Free Indirect Speech and she didn’t even have clever siblings to help her (unlike her opponent). Mullan called this "miraculous".

Austen, we heard, is the greatest writer of dialogue and this Mullan proved by having Sam West and Eleanor Tomlinson portray Mr Elton and Emma (pictured below) in the carriage on Christmas Eve. The audience were rapturous and Kate Mosse, taking the stage to defend Emily Brontë, could not disagree with them.

Convincingly, Mosse conceded defeat before she had even begun, which was clever (even Austenian) of her. Her rousing endorsement of the underdog – little, undernourished Emily Brontë (her coffin only 17 inches wide) – began slowly, gently. It ended with Dominic West as an urgent, desperate Heathcliff, pleading with a beautiful Kathy (Mariah Gale). And then Sam West delivered the final lines of Wuthering Heights:

"I lingered round them, under that benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath, and hare-bells; listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass; and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth."

The world, said Mosse, is a lighter, better place because of Austen, but there must be more to life than marriage. Mosse continued by arguing that, unlike Austen, Brontë does not split men and women up into distinct camps, but looks at what they have in common and in doing so she changed what it was possible for women to write and for men to be.

The fight got just a little dirtier from here. We heard:

- But Austen had to end her books with marriage, because she wrote comedies.

- Mark Twain wanted to dig up Austen and beat her skull with a shin bone (Erica Wagner).

- He’s in denial!

- Brontë was the first punk.

- Brontë's like Tracey Emin.

- Austen, who was my wife’s great, great, great Aunt ... (that one, the audience).

Sam West proposed that you have to be in the right mood to read Austen, whereas Brontë sets the mood; that aside, he wouldn’t want to be in a world without either – which was a very charming and measured thing to say, but by this stage all heads in the audience were twitching to locate the voting boxes which were being passed around.

On the way in the audience polled at:

55% for Jane Austen

24% for Emily Brontë

21% undecided

After the debate, the vote lay at:

51% for Jane Austen

47% for Emily Brontë

2% undecided

So victory for Austen (and also for Mosse who persuaded the undecided to vote in her favour).

The debate continued as the crowd made its way out of the Royal Geographical Society and down to the tube.

- Brontë was so young when she wrote Wuthering Heights, Austen older and more sophisticated by the time she got to Persuasion.

-It’s true that foreigners don’t get Austen.

- No it’s not!

- Austen hates her characters, Brontë loves hers.

- How quick come the reasons for approving what we like! (That one’s Austen, who believed, I believe, in choosing sides).

For more Austen and Brontë in the TLS visit:

Jonathan Sachs on Jane Austen and her World

Michael Caines on How many great novels did Jane Austen write? And other notes from Austenland

Joe Phelan on Emily Brontë's poems

To hear the debate in full, visit Intelligence Squared in iTunes.

February 27, 2014

Gladstone's Library

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Of British Prime Ministers, William Gladstone – whose accent was under discussion on the Today programme this morning: can you tell he was from Liverpool? – stands out as one of the most dedicated bibliophiles. As he acquired more and more books, he got into the habit of awarding his children prizes for finding new places to put them. He would ultimately own more than 32,000, of which he read some 22,000 (he kept a record) and annotated 12,000.

Gladstone’s daughter Mary Drew wrote of his desire “to bring together books who had no readers with readers who had no books”. He was a trustee of the London Library, and helped to found a number of reading rooms. He also saw to it that his own books at Hawarden Castle, North Wales, were used by local people when he was away. Reading, he said, offered a “vital spark to inspire with ideas altogether new”.

When the idea of an E. B. Pusey memorial library was mooted in 1882, Gladstone considered what might be done with his own books after his death; he owned more than Pusey had had, he reflected, somewhat put out, and they covered a wider field. So at the age of eighty-two he bought some land and set up a corrugated iron building three-quarters of a mile from the Castle. With the help of his daughter and a member of his staff, he carried his books there in a wheelbarrow, and arranged them on shelves using a catalogue system of his own devising.

He was creating a library “for the pursuit of divine learning”, open to clergy, theologians and members of the public: having overseen the disestablishment of the Church in Ireland, Gladstone worried that the same would happen in England, and that the Anglican Church (of which he was a committed member) would become a sect, cut off from the important discussions of the day. Even so, the library was to serve not only Christian ideologies, but all of them. For most of its life since, the library has been called St Deiniol’s (it is now simply “Gladstone’s Library”), but Gladstone originally named it Monad – oneness, one, the original number. It reflected his belief that, as long as people studied solidly and seriously, the truth would be served.

After Gladstone’s death in 1898, the present library building was commissioned as a memorial. It was designed by John Douglas, and is considered his masterpiece. A residential wing was added in 1906. A small staff continued to acquire books along the lines Gladstone had himself; almost 40 per cent of Gladstone’s books were what could be labelled theology, and as recently as fifteen years ago, about 70 per cent of those who used the library were clergy.

But since 2009, when Patrick Barkham, the author of The Butterfly Isles, visited and wrote an article about it, there has been a lot of interest from what the library’s warden Peter Francis refers to as “the Hay-on-Wye crowd”. And understandably, I thought, as I wandered round for the first time earlier this month. If you like reading books and perhaps writing them too, why wouldn’t you want to visit a beneficent, historically interesting institution with a spectacular library, a beautiful setting, a studious atmosphere, leather armchairs and a café?

Post-Barkham, Francis saw more clearly what the library’s future would be. He and his staff looked closely at the collections – History and Politics; Religion; Culture, both classical and contemporary; Modern languages; Law. The Law section was over-large and out of date. They refocused the various sections, devised new courses and events, and “boutique-ized” the twenty-six bedrooms. Francis wrote to Damian Barr, who wrote back enthusiastically, suggesting a writers-in-residence programme.

The programme is now in its fourth year. Gladfest was inaugurated last year, which led to Hearth – “an opportunity to meet, talk and create with the Library’s writers in residence and other participants over a weekend of writing related activity”. At the Hearth events I attended, Melissa Harrison, Neil Griffiths, Tania Hershman and Adnan Mahmutović talked about their careers, collectively and individually. Mahmutović, who fled the war in Bosnia in 1993 and now lives in Sweden, led a relaxed discussion about “writing across borders”. Harrison, behind a lectern in the bright and airy chapel, described how she summoned the confidence to start writing fiction in her mid-thirties, and developed a method based firmly on experimentation. She has trouble, she told us, with the question “Where do you get your ideas?”: “It assumes that the writer had an idea at all”. As a member of the library’s staff pointed out, there is no green room, which is part of the appeal. The writers and audience mingle, glasses of wine in hands.

What would Gladstone be doing today?, Francis and his colleagues like to ask themselves. Francis believes that Gladstone would be concerned about the lack of understanding between Islam and the Western world, so an Islamic study room has been set up in the library. Lectures by people such as David Cannadine, Peter Tatchell and A. C. Grayling invite people to consider what Gladstonian liberalism might mean today.

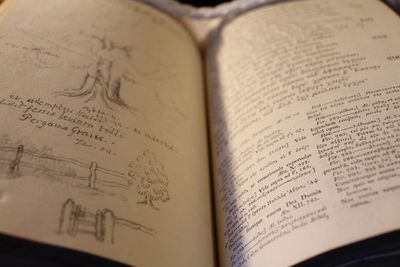

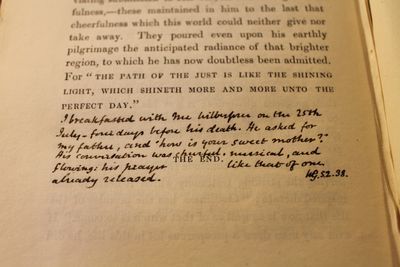

But the main attraction remains the books. Gladstone’s own volumes have recently been gathered together in one place, and new annotations are being found all the time . . . .

Above: Pages from Gladstone's school books

Below: A page from Gladstone's copy of The Life of William Wilberforce by Robert Isaac Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce (1838). On the final page, Gladstone has written: "I breakfasted with Mr Wilberforce on the 25th July – final days before his death. He asked for my father, and 'how is your sweet mother?' His conversation was cheerful, musical and flowing: his prayer like that of one already released".

February 25, 2014

Seventy-five years of Wrath

By MICHAEL CAINES

Five years ago, to mark the seventieth anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath, Robert DeMott wrote a piece for the BBC in praise of John Steinbeck’s “prophetic” novel; he saw it as a work that testified to the tragedy of the Great Depression and that spoke “just as directly to the harsh realities of our own time”:

“At this moment of global economic meltdown, when the whole world is gripped by severe financial recession (much of it caused by rapacious greed, fiscal malfeasance, and corporate arrogance), when groups around the globe are in migration from one kind of tyranny or another, when the gap between rich and poor seems insurmountable, and when homelessness and dispossession caused by widespread financial failure and mortgage foreclosure is rapidly rising in the US and elsewhere – symbolised by shantytowns and tent cities on the outskirts of major metropolitan areas – then it is fitting to think of The Grapes of Wrath as our contemporary narrative, our 21st Century jeremiad.”

Well, here we are, five years on, and apparently little has changed – the gap between rich and poor having in fact increased during the financial crisis – and the relevance of The Grapes of Wrath to the “harsh realities” of our own time has therefore failed to diminish. Hence the event I’m chairing tonight at the LSE, as part of this year’s Space for Thought Literary Festival: Where’s the Wrath Now? (It’s free, by the way, so if you’re in the vicinity, please take this as a last-minute exhortation to come and join us – us being Professors Stephen Fender and John Sutherland, the novelists Maggie Gee and Patrick Flanery, and me.)

It is striking to recall that when Steinbeck won his Nobel, in 1962, he was seen as being out of step, his concerns old-fashioned, and his literary techniques not progressive enough. “Does a Moral Vision of the Thirties Deserve a Nobel Prize?”, the New York Times asked at the time. Writing in the TLS more recently, a New Yorker, Michael Greenberg, took a historically revised view: “there are moments when The Grapes of Wrath reads like an early glimpse of what would become the phenomenon of economic globalization”, its images of “government-sponsored refugee camps and the miserable squatters’ settlements of California” being now “all too familiar”.

There are reasons besides “relevance” to pay homage to Steinbeck’s novel, of course; as well as being an extraordinary story, it has an extraordinary history of its own, as both a bestseller, apparently never out of print, but also an intermittently banned book (formerly banned in Steinbeck’s hometown, for one thing; Stalin banned the John Ford film version), and ritually burned in East St Louis, back in 1939. There is plenty enough for discussion in its supposed faults, too: Steinbeckian speechifying; the “garish” symbolic conclusion, as Morris Dickstein has called it; an impassioned but perhaps misleading progressivism.

I chaired a similar event at the LSE last year, and hope that this one will be just as lively and wide-ranging. Preparing for it has involved less (or rather, no) dipping into the Oxford Book of Parodies, although tributes and parodies could yet come up in conversation, I suppose . . .

February 21, 2014

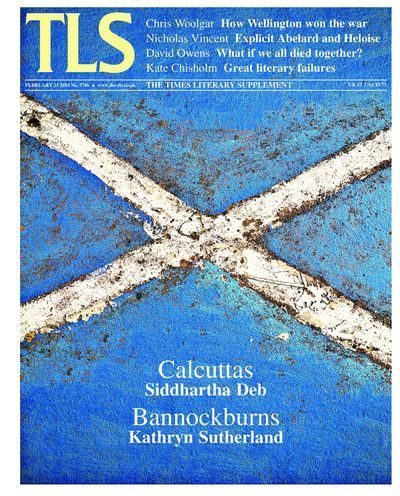

In this week’s TLS – A note from the Editor

Later this year the voters of Scotland will answer “yes” or “no” to the question of their independence. Campaigning by those in favour of and those against a united kingdom is well under way, the latest battlefield being the future of the Scottish pound and the reluctance of all parties in London, themselves united as on little else, to underwrite the feared extravagances of nationalism. The year of the vote has been carefully chosen by those who seek a “yes”, 2014, the 700th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn, the unexpected victory of Robert Bruce over the army of Edward II, an event, as Kathryn Sutherland writes this week, which so powerfully represents “the literary imagination in politics”. The book under review is Bannockburns by Robert Crawford, which, while offering “a severely distorted picture of Scottish writing”, stands proudly in a long history of wars of words.

Calcutta’s history is better understood as written in violence, beginning, as Siddhartha Deb argues, with thuggish British tax collectors, and passing through, inter alia, liberation, communism and an influential fashion for burning trams in the streets. Deb is reviewing Amit Chaudhuri’s account of two years in a city struggling with the modernity that the author “loves so much”, increasingly divided between the well-walled rich and the farcommuting poor.

Chris Woolgar looks at the British wars in India as background to the organization required to defeat Napoleon. The campaign against Tipu Sultan in 1799 gave Colonel Wellesley both the booty and the experience of command that made him Duke of Wellington.

“Sex and philosophy have always existed in close but perilous proximity”, declares Nicholas Vincent at the start of his review of The Letter Collection of Abelard and Heloise. A twelfth-century correspondence between two intellectual lovers, a teacher and his pupil who became castrato and nun, has been the basis of many a romantic fiction. In this 800-page critical edition, edited by David Luscombe and translated by Betty Radice, Heloise’s language, even when kneeling at mass, is “startlingly explicit”.

Peter Stothard

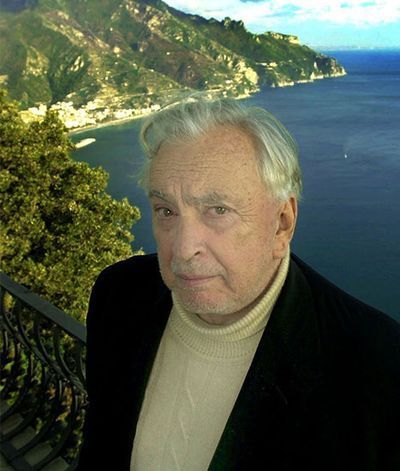

‘You'll get more with Gore'

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

What sort of a politician would Gore Vidal have made? I occasionally asked myself this question over the years as I read another broadside against the US military-industrial complex, another lobbed insult at whoever was president at the time, another lavishly laid-out conspiracy theory, from the pen of America’s most acerbic political and cultural commentator.

As is well known, he ran for office twice as a Democrat, the first time for the House of Representatives in 1960. “You’ll get more with Gore” was his campaign slogan – as he writes in a caption to a photo in his memoir Palimpsest (1995), “No one could figure out what there would be ‘more’ of, but since after a dozen years in Congress the incumbent representative was unknown to his constituents, more of anything would have been an improvement”. He did creditably but, he later revealed, he was campaigning on a ticket of “greed and vanity”. In 1982 he ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic primary in California, but polled some 500,000 votes, apparently without any campaign funding. But these were the early Reagan years, with the Republicans firmly in control. That marked the end of the political career.

It’s hard to imagine Vidal would have made much of a fist of it: too cynical about what’s required to succeed, too socially radical and probably not sufficiently concerned with the “ordinary voter’s” grievances – he was after all “born to the purple”, in Clive James’s phrase. But it might have been entertaining. I sense that writers on the whole don’t make good politicians although a good number of politicians have over the years thought highly of their literary skills.

These thoughts were prompted by the screening of Nicholas Wrathall’s 90-minute film Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia (2013) at the ICA last night (the ICA is running an excellent documentary series – last month I blogged about their screening of a new offering from the French filmmaker Raymond Depardon). Maybe the title of the film could have been more imaginatively chosen – it seems rather a tired Vidalian quip, funny once upon a time. The screening was sparsely attended, which suggests that Vidal (who died in 2012) is receding from memory; that would be a shame as the film showed him to have been remarkably prescient about the US’s ability to make enemies, in the Middle East in particular, and as sharp as a tack until very late on, rolling his eyes as he watched Barack Obama in his acceptance speech in 2008 talking of the United States as a country where anything was possible.

Wrathall splices historical interviews and film – I had never before seen footage of Vidal’s blind grandfather, the reform-minded Senator Tipper Gore, who was such a formative influence – with his own more recent work, dating back to 2005 (we see Vidal leave his Ravello eyrie for the last time two years after the death of his long-time partner Howard Auster – “there is nothing more dispiriting than packing up”). There must have been a time when Vidal was scarcely ever off TV screens in the US and he was certainly a very telegenic performer, trading blows with the conservative columnist William Buckley Jr over Vietnam and (improbably) over feminism with Norman Mailer, pouring scorn on the neocons, publicly humiliating his rival for the Democrat ticket in 1982 Jerry Brown (now Governor of California for a second time, of course), or heaping praise on Mikhail Gorbachev. We see the waspish wit, the exquisite timing, the blue silk shirts. The film reminds us of the fact that Vidal seems to have known everyone. Here is JFK, Tennessee Williams, Paul Newman, Tim Robbins, Hillary Clinton . . . . At one point, the late Christopher Hitchens sidles up to the wheelchair-bound Vidal at a book signing in Washington, but Hitchens had by then joined the pro-Iraq war camp and was less of an “anointed dauphin” to the great provocateur than he had previously been. Hitchens mentions Vidal's fondness for conspiracy theories which many found unpalatable if not irresponsible, such as the idea that FDR was complicit in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Jay Parini, Vidal’s literary executor, talks interestingly about Vidal’s American historical novels (which I have to confess I have never tried to read), rating Burr a “masterpiece”, while Hitchens also appeared to have a high regard for them. Many readers (myself included) have found the later, scabrous novels – Myra Breckinridge, Duluth and so on – hard to read: too self-consciously knowing (postmodernist maybe), the humour rather heavy. But it can't be denied that Vidal kicked off with an impressive quintet of books, utterly diverse in theme and content.

Vidal had published his first novel, Williwaw (above), in 1946, when he was twenty-one, a tightly written and remarkably precocious novel which drew on his own experience on a US Army freight ship in the Aleutian Islands (North Atlantic) during the closing months of the war. He gives the impression of never having needed to be taught how to write a sentence of prose. Williwaw was followed by the novel of post-war adjustment In a Yellow Wood. After that came the controversial homosexual-themed The City and the Pillar, the surely autobiographical account of a difficult mother-son relationship The Season of Comfort and the imaginative reconstruction of Richard the Lionheart’s return to England in A Search for the King. Not bad for openers.

But the essays have tended to be the highpoint in many readers’ estimation. The TLS published a few over the years, on Ford Madox Ford, Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller, Charles Lindbergh, Montaigne – quite a range.

Oh, and while we're on the subject of the TLS, we recently ran a correspondence about "cats on shoulders" (which, as Letters editor, I perhaps over-indulged). Well, here’s just one more, from 1992 (taken from Palimpsest).

February 19, 2014

Timothy McDermott: An appreciation

By RUPERT SHORTT

“The Mass is make-belief – as is Christian faith itself. Faith just happens to be a form of make-belief of which God approves.” Thus Timothy McDermott, Catholic philosopher and former professor of computer science, who has died in Cambridge at the age of eighty-seven. Many of his gnomic remarks were laced with this sort of wry but always gentle humour – another was that “there is no such thing as God in this world”. His underlying point tended to be that we need to know what Christian teaching is and is not saying before being in a proper position to accept or reject it.

His career appeared to fall into two distinct halves. Born in 1926, he joined the Dominican order as a young man and taught theology in England and South Africa before resigning from the priesthood in middle age in protest against authoritarianism in the Catholic Church. He then retrained as a computer scientist in London, returning in due course to South Africa, getting married, and becoming a father and step-father. Yet science and religion were always interlaced at some level. Had he not embarked on ordination training, he would have pursued a doctorate in biochemistry at Cambridge, possibly working at the feet of Crick and Watson shortly before the discovery of DNA.

Like many associated with the Dominican order, he saw in the work of St Thomas Aquinas a rich resource for clarifying debate on the existence of God. Aquinas’s crowning achievement consisted in transposing the works of Aristotle into a Christian key. As Timothy put it in his exemplary book Aquinas (2007), St Thomas found within Aristotle’s emphasis on this-worldly individual experience and agency “a far more potent pointer to God than Plato’s emphasis on the other-worldliness of spirit”. For Aquinas, he went on, “nature does not play second fiddle to supernature: God is . . . not supernatural but the source and author and end of the natural”. For this reason St Thomas held that human reason has its God-given autonomy. Rejecting the separation of faith and reason, he saw the two as complementary means of shedding light on the truth of our being.

In retirement, Timothy noted to his great regret that a new form of the old Platonic–Aristotelian clash was being played out in a fight between religion and science of alarming proportions. He saw the basic misconception at the heart of much New Atheist polemic: “Richard Dawkins and his followers think that theologians are trying to add something on to what it already perfectly explicable by science. But we’re not going outside nature. We’re asking, Where does nature get it from? How is it all possible?”

Take a very simple example like boiling a kettle on a stove. From a Thomist point of view, the process has been misconceived by believers and non-believers alike in three ways. The first mistake is to think that the gas boils the water and that God is not involved at all. The second is that God boils the water and the gas is not involved at all; the third, that God makes the gas act on the water as a puppeteer moves a puppet, and the gas does not exercise a power of its own. For St Thomas, the right interpretation is subtler. As a canvas supports a painting, so God makes the whole situation to exist: the gas, its power and its action on the water. God and the gas work at different levels, not in competition. Were Aquinas alive now, Timothy added, “he would surely have recognised the same struggle of secular and sacred, reason and revelation, material atomism and Platonic reality, in which he was embroiled”. St Thomas’s Aristotelianism was “just the refreshing view we need to resolve this contemporary debate”, he judged.

As a philosopher, he could be withering about the attempt by some scientists to explain how the universe could have emerged from “nothing”, properly understood. He remained adamant that it is impossible, in the terms naturalism allows, to say how anything could exist at all. But his final review – of Steve Jones’s book The Serpent’s Promise (TLS, August 9, 2013) – ended with an insight more important to him than debate about first causes and unmoved movers. According to the monotheistic traditions, he wrote, “the presence of God is not primarily a remote, supernatural, offstage part in the grand narrative of Nature – the ultimate beginning and ultimate end – but an immediate and intimate presence as a centre in the small narratives of human responses to the call to live”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers